The 1908 robbery

In the midst of its financial troubles, on Sunday, 1 March 1908 the Chihuahua offices of the Banco Minero were robbed of almost 300,000 pesos. The thieves got away with a hundred $1,000 notes; 810 $100 notes; 1,580 $50 notes and 1,250 $20 notes as well as more than a hundred $100 notes that had been perforated ‘CANCELADO’.

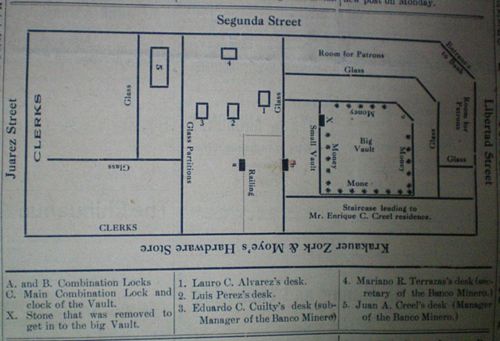

The discovery was made when the bank was opened for business on Monday, 2 March, by Eduardo C. Cuilty, assistant manager and cashier. It seems that his first intimation was the terrible smell of a powerful disinfectant which had evidently been tipped over by one of the robbers on crawling through the hole made in the wall from the document vault (marked ‘Small Vault’ on the map) to the money vault (‘Big Vault’). Cuilty immediately informed the manager, Juan Creel, who in turn informed Governor Enrique Creel, who lived in the apartment above the bank; the bank’s interventor Ramón Cuellar; the jefe político José Asúnsolo, and Martín E. Norman, the judge (Juez 2o de lo Criminal).

The robbers had apparently entered by the main entrance on the corner by means of a key for the side door was bolted on the inside and there were no signs of any window having been tampered with. They then went around back of the railing to the door marked ‘b’ and either knew the combination or worked it with ease and entered the document vault where there were three safes, all the property of Governor Creel, all left unmolested. They then went to the point ‘X’ and with tools bought with them dug a hole through the stone masonry wall, some 18 or 20 inches into the money vault. A peculiar thing is that this was the only point at which in either vault there was no shelving. One man, at least, went into the money vault. Here the robbers met with their first set-back since in climbing in they tipped over the bottle of powerful disinfectant, as strong as aqua ammonia, used in disinfecting banknotes as they came in. The person who tipped it over was evidently overcome by the stuff and called for water which was brought in a ladle which was found left behind. The fumes in a close vault with no safe means of ventilation caused the robbers to hurry up and take the paper money and get out. Although there was much over $1,000,000 in gold in the vault, it was not touched. The robbers went out by the front door in the corner marked ‘Entrance to Bank’ and locked it after themChihuahua Enterprise, 7 March 1908.

Precautionary measures

The bank had recorded the numbers of the $1,000 notes and the next day recalled all those outstanding. Holders were asked to present them at the offices of the bank, or of the Banco Central Mexicano or of any of the state banksEl Chihuahuense, 5 March 1908. Over the next few months the bank also revalidated its higher value notes, by means of a one line overprint of ‘Chihuahua’ and the dateDates ran from 3 March to 15 October 1908.

These measures were slightly counterproductive as many people, in order to avoid any inconvenience or suspicion, began to refuse to accept the bank’s notesEl Correo de Chihuahua, 27 March 1908.

The first arrests

The authorities began by interrogating all the bank’s employees, and arrested several suspects, including:

Moisés M. Navarro: a clerk at the bank, aged 18, a brother-in-law to Francisco C. Terrazas, the manager of the Gómez Palacio branch

Miguel Molinar A.: his friend, aged 18

Francisco Torres:

José Briceño:

Juan Gutiérrez:

Luis Reza:

two of whom were policemen on duty nearby.

The investigation was led by Antonio Villavicencio, the comisario de policia in Mexico City, who arrived on 6 March. The bank also called in experts, including Billy Smith, the famous El Paso detective, and other American detectives. Smith’s opinion was that it was the work of amateur cracksmen and that no American was involvedChihuahua Enterprise, 7 March 1908.

By 6 March some suspectsFrancisco Torres, José Briceño, Juan Gutiérrez and Luis Reza had been released and on 10 March Navarro and Molinar were released. But the following remained in detention:

Anselmo Ruiz: the watchman (velador) on duty on the night of the robbery, who had held the post for more than twenty years, and had a key to the door

Leonardo Mirazo: the policeman (gendarme) who was stationed on the corner at the bank on the night of the robberyChihuahua Enterprise, 7 March 1908

Dámaso Barzola (also Barsola): the office boy (mozo) at the bank, a post he had held for many years, who had a key because he did the early morning cleaning El Norte, 16 March 1908. He was arrested on the first day

Inocente Reyes: According to El Norte Reyes was a master builder, who had done various commissions for the Terrazas, including Luis Terrazas’ Quinta Carolina and overseeing the construction of the bank’s building and vaultEl Norte, , but according to El Correo Reyes was simply a mason and took over during the bank’s constructionEl Correo de Chihuahua, 11 August 1908. He was also arrested on the first day

Leopoldo Villalpando: Villalpando had been an employee of the Banco Minero for nine years, and lately the auditor of the ‘La Equidad’ life insurance company. He apparently drew attention to himself because at the time the robbery was discovered he appeared and asked for a reward for exposing the thieves. His eyes were very irritated (supposedly from the formaldehyde that had been spilt) and as he had a poor character he was held incommunicadoEl Norte, 16 March 1908

Wulfrano Villalpando: Leopoldo’s brother, who had a business hiring out chairs, and who had worked for some of the principal players (the Creels and General Terrazas) as an agent or rent collector. He was arrested on the Monday evening El Correo de Chihuahua, 15 April 1908.

As the net widened others who were implicated were:

Federico Cuilty, hijo: first cousin of Enrique and Juan Creel, who worked for himself in mining in La Noria, and who was arrested on 8 March on a warrant made out by judge NormanAt 2.00 p.m. on 8 March the Comandante de Policía and two secret policemen came to the house he shared with his family and shown him an arrest warrant made out by Juez 2º de lo Penal, Martín E. Norman. He was taken to the Comisaría Central de Policía and held incommunicado and badly treated. A fortnight later he was transferred to the Cárcel Pública and thrown into a loathsome dungeon (arrojado á un inmundo calabozo) where he stayed two months and six days without air or light (El Correo de Chihuahua, 2 September 1908)

Ignacio Macías: another mason

[ ]: Macías’ wife, on 13 March and held incommunicadoEl Correo de Chihuahua, 21 March 1908

Zeferina N. de Ornelas: the woman with whom Barzola lived

Andrés Barzola: Barzola’s sonEl Norte, 18 March 1908

[ ]: Barzola’s wifeibid.

Felicitas Cadena de Rentería: a cousin of Barzola’s wife, arrested on 15 MarchEl Correo de Chihuahua, 21 March 1908

[ ]: Zeferina’s husbandEl Correo de Chihuahua, 24 April 1908

Tomás Almanza: Zeferina’s son, aged 18-20ibid.

Francisco Durán: a 15-year-old friend of Tomás AlmanzaEl Norte, 18 March 1908

[ ]: Inocente Reyes’ wifeEl Correo de Chihuahua, 24 April 1908

Félix Corona: a baker

Librada Mendoza: Corona’s girlfriendEl Correo de Chihuahua, 31 March 1908

Jesús Moreno de Villalpando: Leopoldo’s wife whose violent treatment caused her to give birth prematurely on 18 MarchEl Correo de Chihuahua, 21 March 1908

María Guadalupe Mejía de Villalpando: Wulfrano’s wife: El Correo de Chihuahua, 24 April 1908

Finally, one should mention in passing

Dolores: from a familia Polanco

Carmen: from a familia Polanco

Enriqueta: a young girl of 14 or 15

Tomás: a young boy of 9 or 10, all arrested on 23 MarchEl Correo de Chihuahua. 24 March 1908

though these last four were released the following dayEl Correo de Chihuahua, 27 March 1908, and

Apolinar Cuevas: arrested at the same time as Federico Cuilty but released for lack of evidenceEl Tiempo, 14 March 1908.

As was to become evident later, the authories flagrantly abused their powers. Suspects were arrested without warrants, held incommunicado and in dire conditions, mistreated and even tortured. Bank officials such as manager Juan Creel and lawyer Joaquín Cortazar, hijo took part in the investigations, whilst prime suspects were interrogated personally by Governor Enrique Creel. A biased running account of developments was given out by the Creel paper, El Norte.

By 21 March Barzola and Zeferina Ornelas and her son, Tomás Almanza, had confessed, though there were various discrepancies in the newspaper accounts.

According to El Norte Reyes had planned the robbery for some time, perhaps since he had constructed the vault, and may have had to act when he did because the bank was moving to new premises across the Plaza. He needed an accomplice to open the safe and this was Leopoldo Villalpando who had somehow learnt the combination during his years at the bankEl Norte, 16 March 1908. At 3.00 on the Sunday afternoon Reyes, Leopoldo and Wulfrano Villalpando and Barzola himself met up in the Plaza with the mason, Ignacio Macías. At an opportune moment, when the street was empty, they entered the bank, where they stayed hidden until they judged it right to begin digging. Inocente Reyes made the hole, working through the afternoon and evening until it was big enough to get through. Then Leopoldo Villalpando and Ignacio Macías entered the vault and took the notesibid..

In a later version in the same El Norte and in the Chihuahua Enterprise, in which he tried to lessen his own responsibility and also possibly because of inconsistencies that had become apparent (see below), Barzola said he had gone down to the Plaza de la Constitución between 2.00 and 3.00 on Sunday afternoon to look for his boy, Andrés, who had not come home to eat, when Leopoldo Villalpando had asked him for the key to the bank to get a document he had forgotten. Barzola said he thought it all right to hand over the keyWhy, as Villalpando was not a bank employee?. Barzola saw Leopoldo join his brother Wulfrano, Inocente Reyes and Ignacio Macías, and together they went down calle Segunda next to the bank. Barzola was at the bullfight in the Parque Lerdo and went home at around 8.00 or 9.00. Some time later Ignacio Macías Inocente Reyes, according to the Chihuahua Enterprise (Chihuahua Enterprise, 21 March 1908). came to fetch him and said Villalpando wanted to speak to him. The two went and Barzola said he found himself drawn in to the robberyEl Norte, 20 March 1908: Chihuahua Enterprise, 21 March 1908.

The entry to the bank was made before the close of the band concert in the plaza, probably about 10 o’clock. Leopoldo Villalpando had no trouble in opening the door to the document vault by the combination and then removed the lock after he got in. Then Reyes, with chisels, hammers and pieces of steel took out the mortar from the internal wall to get into the money vault. The removal of plaster knocked over the bottle of disinfectant in the second vault. Leopoldo Villalpando, Reyes and Macías entered the second vault and Leopoldo had some difficulty in getting open the safe containing the higher-value banknotes. After taking out the money Leopoldo took his pencil and divided it upEl Norte said that the robbers shared out the spoils in Zeferina’s house (El Norte, 16 March 1908). The robbers were in the bank for about three hours, and were dividing up the money when they heard someone trying the corner door and they hid under the counter. The Villalpandos with their portion were let out of the side door. Barzola locked it, and a little later he and Reyes went out at the main door, Barzola locking it with his key. These two then went to Zeferina’s house on calle Mina. Barzola says they gave her five $1,000 notes. Reyes asked if they could leave the equipment in Barzola’s house but he refused, so they left them at Ornelas’. A little later Barzola, Reyes and Zeferina went down the avenida Ocampo, crossed the river, went over beyond the old smelter and in a little arroyo Reyes told Barzola to wait while he and Zeferina went ahead and buried the moneyAccording to the Chihuahua Enterprise Zeferina said she buried hers in a pile of rags on the river bank (Chihuahua Enterprise, 21 March 1908). However, no money was found at the point where it was alleged to have been buriedChihuahua Enterprise, 21 March 1908 and El Norte commented that it was believed that this was just a ploy on Reyes’ part not to share with his accomplices and that he returned and reburied the money somewhere elseEl Norte, 20 March 1908.

According to El Norte, Zeferina finally confessed that Inocente Reyes and Dámaso Barzola had planned the robbery at her housewhich contradicts Barzola’s own testimony; that very late on the Sunday night they had arrived at her house with two others, bringing their tools and the money, which they shared out, giving her five notes of an unknown denomination. Her son, Tomás Almanza, who had been held incommunicado, admitted the same, adding that the notes that his mother received were $1,000sEl Norte, 16 March 1908. Tomás offered to show where he had hidden the notes that Zeferina had received, and on 18 March set off in a carriage with Norman, Villavicencio and comandante de policía Antonio Piedras but then changed his mind and said the notes were not thereEl Norte, 19 March 1908.

Agustín (sic) Macías apparently then made a declaration agreeing with that given by Barzola, Zeferina and Tomás AlmanzaEl Norte, 27 March whilst Barzola’s wife said that unusually he spent the Sunday night away from home.El Norte, 19 March 1908.

Discrepancies appear

The Villalpandos, Reyes and Macías originally maintained their story of innocence and holes began to appear in Barzola’s account. For example, contrary to Barzola’s first confession some employees of the bank, including Navarro and Mateus, had been in the bank after 3.00 p.m. and until about 8.00 p.m.El Correo de Chihuahua, 20 July 1908 and though the robbers were meant to have entered the bank at 3.00 p.m., some people had seen Reyes and his family at the Presa del Río Chuvíscar at the same time as he was allegedly making the hole in the vault wall, and he had then socialised with friends until late at nightEl Correo de Chihuahua, 20 March 1908. Reyes had arrived at the Sociedad Juárez de Obreros at 1.30 on Sunday afternoon and stayed there until 4.00. At that time Victoriano Máynez invited him to the bullfight, but Reyes declined, as he had already agreed to go with his friend, J. Ascención Ruvalcaba, to see the work on the Presa del Río Chuvíscar. Just then a carriage driven by Ascención’s son, Manuel Ruvalcaba, arrived and they set off, together with a Francisco Acosta, from San Buenaventura, who happened to be at Ascención’s house. Several people witnessed the party on the way to and from the dam, where they spent the best part of the early evening, including the family of Federico Margaillán, a well-known merchant, and José Asúnsolo, jefe político of the Iturbide district, with whom they had exchanged greetings when passing the Quinta Esperanza. When they arrived back in the city, the gentlemen dined at Ruvalcaba’s house, leaving at 9.15. Reyes then returned to the Sociedad Juárez de Obreros, where he stayed until 10.30, as the barman, León Avila, and others could attest. Then Reyes took carriage number 130, of Antonio Cordero, and made several visits until 3.45 in the morning, when he was driven to a well-known menudería (a restaurant specialising in menudo, a revolting sort of restorative soup made from tripe) El Correo de Chihuahua, 21 March 1908: El Correo de Chihuahua, 15 April 1908.

From about 3.00 on the Sunday afternoon Leopoldo Villalpando had been at home, socialising with various families including that of Daniel Carvajal. Between 6.00 and 7.00 Villalpando went to Carvajal’s house, retuning home at 8.30. He continued socialising with members of the Carvajal, Acosta and other families until 11.30El Correo de Chihuahua, 15 April 1908.

Wulfrano Villalpando had got up at 7.00 on 29 February and after breakfast went and bought china paper to make flags to sell at the bullfight at Nombre de Dios on the following day. Villalpando, his wife María Guadalupe Mejía, and young lad, José Ronquillo, spent the day making flags. After dining at 5.00, they went to the “El Buen Tono” cinema, returning home at 9.00. On Sunday Wulfrano got up at 7.00 and did various tasks in the morning. At 2.45 in the afternoon, when Jesús (sic) arrived, they load the carriage with chairs, to take to the Parque Lerdo, and on returning, Wulfrano went with his wife to Nombre de Dios, where they arrived at 3.45. Several people could attest to his presence in Nombre de Dios, where he hired out cushions, including José María Peinado and Dionisio Ontiveros, the collectors at the bullring, the Presidente Municipal and Tesorero Municipal, and Reinaldo Delgado, who said he sold Villalpando two orange and was still owed eight centavos!El Correo de Chihuahua, 24 April 1908 and the musicians in the bandEl Correo de Chihuahua, 21 March 1908. When the bullfight finished at 6.00, the party returned to Chihuahua, and spent from 7.30 until 10.45 in the Plaza de la Constitución, the Parque Lerdo and at the chinese restaurant in avenida Independencia. Among the many people who remembered seeing them in the Plaza was the Tesorero Municipal. After dropping off his wife Villalpando returned to the Plaza de la Constitución at 11.35, when his boys were still collecting the chairs. After a couple of trips, Wulfrano was already in bed by 1.30, when his boy came to complete the accounts for hiring out the chairs. On the Monday Villalpando spoke with local judge Salvador González; Jesús L. Irigoyen; Lic. Urbano Fabela; General José María de la Vega, Jefe de la 2ª. Zona Militar, and various others. He was arrested on the Monday, on returning from the cinema with his wife. Moreover, the Villalpando brothers had fallen out over some matter over a year before and so would not have co-operated together in planning the robberyEl Correo de Chihuahua, 15 April 1908.

Originally, judge Norman had, on the evidence available, considered Macías innocent and on 15 March had ordered his release, though on receipt of the order the warden (Alcaide) Manuel Leyva had stated that Villavicencio had given him an expressed order from Governor Creel not to release Macías under any circumstancesibid.. By 28 March Macías had confessed and corroborated Barzola’s story. Still no money was recovered.

It is uncertain why such a highly placed person such as Federico Cuilty, hijo, should have come under suspicion. Even the Secretario de Hacienda, José Limantour ,wrote to Enrique C. Creel on 13 March that he was saddened that the judge had felt it necessary to act against a member of his familyCEHM, Fondo Creel, 86575. But the investigators believed that Cuilty had been with at Maciás’ house and the fact that, according to the evidence of the suspects, Joaquín Cortazar, hijo was willing to pay $5,000 for someone to incriminate Cuilty suggests deeper motives.

Federico’s story was that on 28 February his father, Federico Cuilty, had summoned him to Chihuahua by telegram because his mother was gravely ill. He arrived late on 28 February and spent the next day at his mother’s side. He spent the Sunday visiting friends and returned home late at night. Between 1.00 and 2.00 on the Monday morning the doctor, Pedro M. Muro, was called to administer an injection and saw Federico asleep in his room. At about 3.00, one of the sisters, in passing his room, saw Federico asleep with his arm dropped, and carefully lifted it without disturbing his sleep. At about 6.00 a.m. he was awakened to take the train back to Bustillos, to collect some medicinal spring water for his motherEl Correo de Chihuahua, 15 April 1908.

Despite the sensational reporting by El Norte, elsewhere disquiet was beginning to be expressed about the treatment of the prisoners, that they were being held incommunicado and given one meal a day, and a fund was started for their support and defence. It was rumoured that the bank's owners were somehow implicated in its robbery.

The letter and $1,000 notes

Then on 1 May Silvestre Terrazas, editor of El Correo de Chihuahua and a violent opponent of the Terrazas-Creel hegemony, received a package in the mail containing a quarter cut from each of the stolen $1,000 notes. They were accompanied by an anonymous letter, postmarked Ciudad Juárez (though possibly posted in Chihuahua) briefly disclosing how its author, who gave his initials as C A J, had robbed the bankIn March Enrique C. Creel had already received two anonymous letters written on the same typewriter that was eventually traced to the bank (CEHM, Fondo Creel, 86566, letter Creel to Limantour, 29 October 1908). Terrazas went to see interim governor José María Sánchez and found that he had received an identical package. The judge in charge of the case, Martín Norman, and the bank's solicitor, Joaquín Cortazar hijo, also received identical packages.

Terrazas did not publish the letter but the Chihuahua Enterprise reported that the writer claimed that there were only two in the robbery and that the persons in jail were innocent. The writer said that one robber left for Torreón at once and the other was in Chihuahua for a while after the robbery. The writer explained that they were going to Europe and would be there before the four parcels of fragments posted by an innocent friend would reach the people to whom they were addressedChihuahua Enterprise, 2 May 1908. In fact, most of the Chihuahua Enterprise’s report was fantasy. When Terrazas did later publish the letter, its contents were as follows:

Those currently accused had confessed either because they had been bought by the Banco Minero (which was impossible, as unnecessary) or the victims of such extreme punishment that they had lied.

The writer had first visited the bank in November 1905, and soon devised the idea of robbing it when he saw the thinness of the internal walls. He studied the comings and goings of the staff and the layout of the bank, and by luck managed to get a mould of the front door key and make a copy. One Friday night, with an accomplice on lookout, he made a foray into the bank to check the last piece of the puzzle, namely the combination of the vault door. This proved easy to pick. He also identified the best place, above an iron cabinet, to break through.

He planned the robbery for 15 April, the Wednesday of Holy Week, since the bank was to be closed on the Thursday and Friday, but then heard that the bank was to move premises on 25 March, so brought forward the date to Saturday, 29 February. By 6.00 p.m. he and his accomplice were sitting on a bench in the plaza, with their tools, but the last two employees did not leave until 11.00, giving the key to the night watchman. At about midnight the watchman went to the door, and as there was not enough time, they decided to postpone the attempt to the following day.

By 8.00 p.m. the two robbers were in the Plaza, and at 9.20 slipped into the bank. The writer decided not to make the hole above the cabinet as they might be heard in the apartment above, but elsewhere. Because of obstacles and setbacks it took four hours to make the hole, and another half hour to enlarge it. The writer gave a detailed account of his excavation and of the layout inside the vault. He also had to ask his companion for a drink of water as he was in danger of passing out from the unknown fumes. He ignored the safe boxes containing packets of $5 and $10 notes and $5 and $10 gold coins, and concentrated on the larger notes, which he was confident of cashing inside Mexico. He passed these notes through to his accomplice, who put them in a wire basket. When he had finished, almost asphyxiated by the fumes, he climbed back through the hole, leaving behind the ladle of water.

In the outer vault he counted the money, which was almost $300,000, including a hundred $1,000 notes. There was also a sealed package marked “Deposited by order of the Juzgado Primero (or Segundo) de lo Penal” containing approximately $5,000 in notes of the Banco de Londres y México (including two $500 notes). As the writer had calculated that he had taken about 500,000 pesos, his first thought on discovering his mistake was to go back and get some more, but fearing for his life, he satisfied himself with the $300,000. He remarked that there was a very marked difference between the specification of the notes that the Banco Minero gave to the press and his own account. He could not say whether the $10,000 in mutilated notes that the press mentioned actually existed.

The two robbers waited a couple of hours, spending the time examining the contents of various safe deposit boxes and then left at 5.50. The writer took the train to Torreón at around 7.00 in the morning, and went on to Mexico City. His accomplice stayed in the city, but later left for Sonora where he exchanged his notes. Meanwhile the writer changed his notes for notes of other banks and later bought some drafts drawn on various European and American banks.

The writer enclosed the quartered $1,000 notes, although he could have exchanged some of them, for three reasons: firstly, so that those innocently imprisoned would be released and those who had forced them to lie exposed: secondly so that the press would publish the complete history of the robbery; and lastly because his companion had told him that almost all Chihuahua believed that the bank had been robbed by its owners, and he wanted to dispel this rumour.