Cartones of Huixquilucan

by Ricardo de León Tallavas and Emilio Javier Ramírez García

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

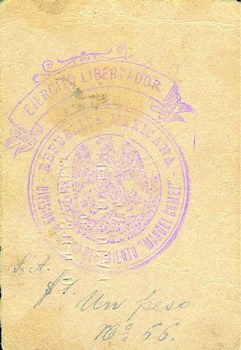

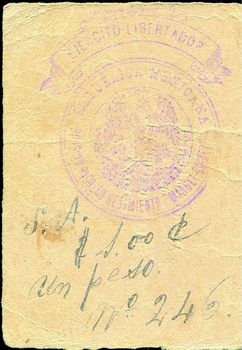

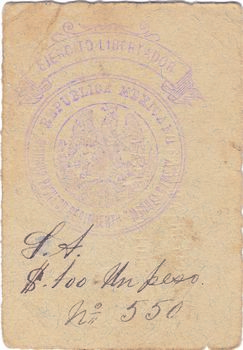

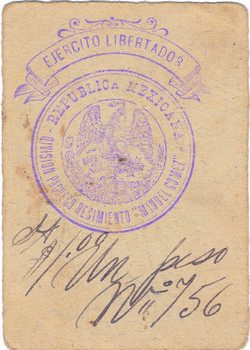

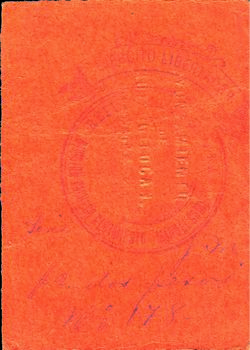

In September 2021 a very small group of an unknown issue of Mexican Revolution cartones surfaced. All together this group is a mere 15 piece set in two denominations: one and two pesos. The serial numbers for the one peso are 66, 171, 202, 246, 251, 304, 318, 329, 401, 464, 550 and 756. The two pesos are just three: 178, 198 and 277. All of them are handwritten, all the one peso read: “SA. $1. Un Peso. No. ___”. Possibly the “S.A.” meant Serie A as the two pesos notes bear the wording “Serie JM”, possibly being the initials of the author of this particular denomination or issue. All 15 cartones bear a rubber stamp in violet ink reading: EJERCITO LIBERTADOR - REPUBLICA MEXICANA - DIVISION PACHECO REGIMIENTO “MANUEL GOMEZ” (LIBERATING ARMY – MEXICAN REPUBLIC – PACHECO DIVISION “MANUEL GOMEZ” REGIMENT). Their size is about 111 x 63 mm and all of them are made in regular cardboard: cream color for the one peso and red for the two pesos. All are also embossed with the wording “AYUNTAMIENTO DE HUISQUILUCAN” (sic) (Town Council of Huixquilucan). They are missing a date and bear no signature.

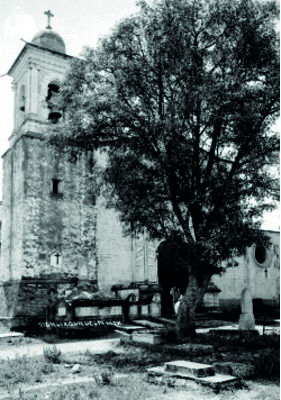

Let us begin with the clues on the cartones themselves to start finding their historical context. Huixquilucan is now a small town founded on 1 January 1826 in the Estado de México (State of Mexico). Its meaning is “place where edible thistles grow”. Today it is located barely 28 kilometers (17 miles) southwest from the limits of Mexico City. This small place was a crossroads for several armies that came or went from or to the capital city of Mexico during the time of the Revolution.

The Pacheco Division was a powerful group of Zapata’s Ejército Libertador del Sur (Liberator Army of the South) led by Francisco Vargas Pacheco, a self-made general, one of the thousands appointed arbitrarily by the Mexican Revolution. He was born in Morelos state and was one of the earliest civilians that publicly acted against the Díaz dictatorship, favoring Madero in his home state. After March 1912 he started expanding his area of military operations to the neighboring State of Mexico. Pacheco was under the command of Genovevo de la O Jiménez, another self-made Zapata general. By 1914 Pacheco was equal to de la O in rank which eventually caused frictions between them. Pacheco had several brigades or regiments under his command, one of them being led by Manuel Gómez, one of many obscure characters during the Mexican RevolutionDiccionario histórico y biográfico de la Revolución Mexicana, Instituto Nacional de Estudios Históricos de la Revolución Mexicana, Secretaría de Gobernación, 1991, pp. 791 – 792: John Womack, Zapata and the Mexican Revolution, Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, US, 2011, p, 251.

The Pacheco Division was a powerful group of Zapata’s Ejército Libertador del Sur (Liberator Army of the South) led by Francisco Vargas Pacheco, a self-made general, one of the thousands appointed arbitrarily by the Mexican Revolution. He was born in Morelos state and was one of the earliest civilians that publicly acted against the Díaz dictatorship, favoring Madero in his home state. After March 1912 he started expanding his area of military operations to the neighboring State of Mexico. Pacheco was under the command of Genovevo de la O Jiménez, another self-made Zapata general. By 1914 Pacheco was equal to de la O in rank which eventually caused frictions between them. Pacheco had several brigades or regiments under his command, one of them being led by Manuel Gómez, one of many obscure characters during the Mexican RevolutionDiccionario histórico y biográfico de la Revolución Mexicana, Instituto Nacional de Estudios Históricos de la Revolución Mexicana, Secretaría de Gobernación, 1991, pp. 791 – 792: John Womack, Zapata and the Mexican Revolution, Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, US, 2011, p, 251.

From 24 May to 10 October 1914 Francisco V. Pacheco was named Secretary of War by the government of the Villa-Zapata Convention, and by 24 November he was entering into the city of Toluca, capital of the State of Mexico. Pacheco was then in charge of the general area adjacent to Toluca. Huixquilucan is located about 40 kms (25 miles) northeast of Toluca.

However, in our opinion, these cartones cannot be earlier than 1915 as it was not until 13 June of that year that he informed that he was finally in charge of the general area of Texcoco “stopping any enemy (Carranza) advancement to the zone”, and mastering the area for his direct influenceArchivo Histórico de la Defensa Nacional, XU481.5/304, ff. 89-91. On 15 October 1915 the Zapatista governor of the State of Mexico, Alejo G. González, declared all enemies (Carranza) issues to be null and void. This could have been a good reason for these cartones to have been issued, namely the perennial lack of money.

There is evidence that Francisco V. Pacheco requested permission to produce money of his own even before gaining control of the Huixquilucan region. The reason was the quick depreciation of the state paper money issues in some parts of his military jurisdiction. Pacheco asked Zapata at least to issue a decree to either dictate the regulation of prices to the “abusive merchants” or command the complusory acceptance of their Zapatista paper money at full face value “because it is impossible to face the enemy if defeated by hunger beforehand”letter from Pacheco to Zapata, at his headquarters in Huitzilac, Morelos, 5 August 1915, AHUNAM, Fondo Gildardo y Octavio Magaña Cerda, caja 77, expediente 67, foja 5.

In the 1910 Census Huixquilucan appears as part of the District of Tlanepantla. This district included the towns of Tlanepantla (the administrative centre), Coacalco, Ecatepec, Jilotzingo, Naucalpan, Iturbide, Zaragoza, Huixquilucan and Nicolás Romero. It is recorded that the whole district then had 60, 302 inhabitants. The area of this region was made of four small towns and 58 villages, with Huxquilucan as one of them. Even though Huixquilucan was a village, by 1914 it counted with a steam powered mill as one of the principal industries, with the male operator earning 50 cents daily and each of the two female laborers 25 centavos. The businesses recorded mentioned that Huxquilucan had four general stores, 16 neighborhood grocery stores, five meat markets, four bakeries, two riggings, one clothing store and 34 pulque bars. Also, the settlement had two pharmacies and four entreprises producing bricksAmada Esperanza Baca Gutiérrez, Huixquilucan, Monografia Municipal, Instituto Mexiuquemse de Cultura, 1998, p. 144.

As for Manuel Gómez, the leader of the brigade or regiment that stamped these issues, we have very little to go on. Merely a citation that he was born in the State of Mexico. Also it is noted that Gómez eventually was in charge of the Toluca Brigade, which leads anyone to believe that these self-made generals were leading one small military group after anotherDiccionario de Generales de la Revolución, Instituto Nacional de Estudios de la Revolución Mexicana, México D.F., 2014, vol. 1, p. 435.

As for the issue we could deduce a couple of things: first, that this was a military issue that was backed by the Huisquilucan (sic) Town Council as it bears its name embossed on each carton. Second, the total issue should have been very small because of the numbers found on the notes themselves. They range up to 756 for the one peso and 277 for the two pesos denomination. A conservative assumption would probably be $1,000 in the one peso denomination and maybe $500 for the two pesos, making the total issued of no more than two thousand pesos.

These cartones are written by seven different people. The first writer made the one peso notes 66, 177, 304, 318, and 329; the second did cartones 202, 246 y 251; the third was the author of note 464; the fourth wrote 401 and the fifth the one numbered 550. A sixth writer is distinguished by the style of his calligraphy in 756. The two pesos bear two distinct penmanship styles, one for 178 y 198 (very possibly done by the first writer), and another one for the 277 cartón (the seventh writer).

So far there has been one precedent for the mention of a Pacheco military unit on paper money. Three notes ($1, $2 and $10), modelled on the Tesorería General del Estado de Chihuahua issue dated 10 December 1913 bear the stamp of the “Detall” or Archival and Legal Processing Office of the Brigada Pacheco. However, the provenance of these stamps is very debatable because the range of operations of the Pacheco Brigade was very flexible.

In conclusion, these 15 cartones that have just arrived to our numismatic world are exciting news and proof that not everything has yet been found.

(published in the June 2022 journal of the U. S. Mexican Numismatic Association).