Henry Middleton, the Banco de Jalisco forger

Henry L. Middleton was a lovable twenty seven-year-old con man involved in the counterfeiting of Banco de Jalisco banknotes. In the best tabloid tradition the Washington Times of 9 August 1910 reported that “H. L. Middleton, handsome, debonair, and evidently a fair-haired child of fortune, appeared in New Orleans last April and almost immediately was admired by men and beloved by women.

“Smiling always and content only with the best that life afforded, he wandered down the primrose path of dalliance hand in hand with mirth. Money was nothing to him. No pleasure or luxury cost so much that it was beyond his reach. He tickled his palate with the best of wine, and charmed his ears with the sweetest music to be heard in the best cafes of the city.

“He used the money not only to buy the good things of life, but also to deal extensively in real estate and in stocks on margins. The swath he cut in society was not wider than the row he hoed in businessWashington Times, 9 August 1910.”

One source for Middleton’s fortune was to attempt to cash counterfeit Banco de Jalisco notes with various brokers in New Orleans. His downfall came because of a simple mistake. One such broker received a note from Middleton by messenger boy, enclosing 200 pesos in five peso notes, to be exchanged for dollars. The broker spotted that the signatures had been left off several of the notes and he handed all the money back to the messenger boy. Later, thinking the matter over, he noticed Pat Looby, the Secret Service agent stationed in New Orleans, and told him. Looby got onto Middleton’s trail, but found nothing on which to arrest him until two days later, when another broker received a letter through the post from Middleton, who, signing a fictitious name, asked that $150 be mailed to him at a certain post office box in exchange for the pesos he enclosed. Looby waited at the post office and nabbed Middleton as he called for his mail on 3 April (ABNC, folder 259, Banco de Jalisco (1907-1932)).

When cornered, Middleton took Looby to a safe deposit vault and gave up seven unbroken packages of 500 notes each and 115 notes lying loose. He also took Looby to a broker’s office, where two packages of 500 notes each were found. “Had he not forgotten to leave off the signatures on some of the notes, he might yet be dealing in stocks and real estate – might still be a commanding figure in the cafes of New Orleans, and might yet be admired by men and beloved by women.” In fact Middleton probably had a small window of opportunity for once one of his notes had been presented to the bank in Guadalajara the deception would immediately have been recognized and the bank would have put out a circular alerting everyone to the counterfeit notes. Moreover, given that Looby recovered 4,915 notes (assuming that 300 had been sent to the second broker), out of a print run of 5,000, only 85 at the most will have been passed. This did not stop the newspapers from embellishing the tale and on his conviction one wrote “Several bills had been successfully unloaded on innocent victims, and the scheme proved to work so easy that the slick swindler thought that he would go into the real estate business, and nothing less than a $10,000 home would suit him as a first investment. Having surveyed the lower portion of the city, visiting numerous houses, he finally settled on the Dunbar home in Esplanade Avenue, which was then offered for sale. Negotiations were forthwith entered with a well-known agent, and the final word for the purchase of the property was left with a well-connected young lady, whom Middleton had promised to make his wife. Of course, Middleton counted on the lack of experience of the agent, but it happened that the latter was, in the contrary, fully alive to the situation, and was not of the kind to be taken in by the golden promises of the would-be purchaser. Middleton was made to give a deposit, and when he placed $4,000 of the bogus Mexican money wrapped up in a sealed package in the hands of the agent the dig was upTimes-Picayune, New Orleans, 15 May 1911.”

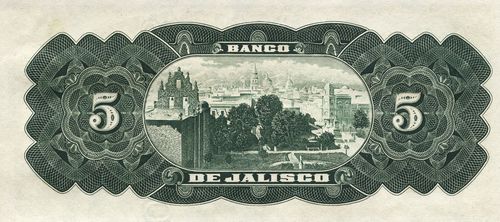

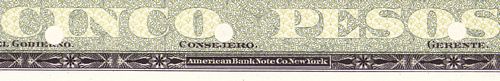

M386 $5 Banco de Jalisco counterfeit remainder

M386 $5 Banco de Jalisco counterfeit remainder

The five thousand counterfeit notes had been printed by the National Bank Note Company of Philadelphia and forwarded to the Bank of Jalisco, care of Thomas Marshall, New Orleans by the Southern Express Company. The company said that in February 1910 they had received the order from Middleton in New Orleans, who claimed to be a representative of the bank and said that the bank was unhappy with the American Bank Note Company and wanted to try another firm. He provided written authority of the Mexican officials for the printing, and instructed the printers to ship them to Thomas Marshall.

The National Bank Note Company said they had received from Middleton what he called a certificate from the Minister of Finance and which they, as they stated to the Secret Service Department, accepted in good faith. However Bartning, the manager of the Banco de Jalisco, later wrote: “after having seen a photographic copy of the last page of this certificate, it is almost impossible to understand how any reasonable person could accept that that thing as a certificate from the part of this Government, In the first place it was written in English, and any one must know that the Mexican government will no more extend a certificate in English than your Government would give one in Spanish. The signature of Limantour appears as Minister of Finance, and that of Gregorio Hermosillo as Secretary of Treasury. Now Secretary of the Treasury is English for Ministro de Hacienda, and there do not exist two such charges. We have a Tesorero de la Hacienda besides the Ministro de Hacienda, the same as there is U.S. Treasurer. Lastly there was affixed the signature of Miguel Ahumada as Manager of this Bank. All these signatures were not imitations of the real signatures but just were written as Middleton pleased. The name of Limantour was written Limanturo, and all were evidently in the same handwriting”. Middleton also stated that according to Mexican Customs laws, the Express Co could not take banknotes into Mexico, and the bank would send a messenger to New Orleans to get them there and bring them into Mexico. This messenger he called Thomas Marshall, whom he made Vice President of the bank. The National Bank Note Company forwarded the notes to Marshall in the middle of Julyletter of Bartning to ABNC, 9 September 1910 (ABNC, folder 259, Banco de Jalisco (1907-1932)).

In the National Bank Note Company’s defense it can be seen that there was no attempt to make a complete replica of the American Bank Note Company’s note, which would have made them complicit in forgery. As well as the obvious change in printer’s imprint on the front and absence on the reverse there are noticeable differences in the size of various elements, in the fretwork of the borders and surrounding the shield and denominations, in the text of the legend (different type, no accent on“PAGARA”, no comma after “México”) and in the date (“de de” instead of “de de 19”). The company was, however, probably too naïve and too keen to gain a march on the American Bank Note Company.

At first Middleton claimed that Marshall, whom he knew as vice-president of the bank from his own time in Guadalajara, met him in New Orleans and told him that the notes would arrive soon, and as he, Marshall, was in a hurry to leave for Mexico, he would give Middleton authority to receive them from the express company and thereafter take them by steamer, via Veracruz, to Guadalajara. Middleton told Marshall that he was in need of funds and so Marshall told him that he might use $250 in gold of these notes for himself. Marshall had signed one of the notes, with the names of three bank officials, and told him that he could do the same on the other notes that he neededSD papers, 812.5158/11.

Middleton was brought before United States Commissioner Henry Chiapella and committed to the Circuit Court for trial, charged with having obtained money from Otto Maier, the Camp Street broker, and the Commercial-Germania Savings Bank and Trust Company. Judge Chiapella originally fixed Middleton’s bond at $1,000, but as there was a flight risk it was increased to $2,250. On 23 August Middleton was released on bondTimes-Picayune, New Orleans, 24 August 1910.

On 15 November the Department of Justice asked the Secretary of State to instruct the appropriate United States consul in Mexico to secure a certified copy of the original charter or concession granted to the Banco de Jalisco and other documentation needed for use in the prosecutionSD papers, 812.5158/12. However, on 14 May 1911 Middleton pleaded guilty to forgery and using the United States mails to defraud and was sentenced to two years in the Federal Penitentiary in Atlanta, Georgia, so the certified copies were no longer requiredSD papers, 812.5158/14; Times-Picayune, New Orleans, 15 May 1911.

It is obvious that Marshall (as portrayed by Middleton) did not exist, so the only question that some people consider unanswered is how Middleton paid the $1,025 invoice for the notes. He probably did have an accomplice, possibly someone of high rank in the Banco de Jalisco, who could have ensured that the counterfeit notes were put into circulation in a brief space of time. However, although this venture was a failure, Middleton himself does seem to have access to funds. Perhaps the debonair organist’s appeal to young women (even though he seems to have had a wife and two children) might provide the answer.

When the Banco de Jalisco discovered that the National Bank Note Company had issued and delivered a quantity $5 notes to a party who represented himself as Vice-President of the bank, on 9 August it asked the ABNC to tell it whether it had delivered any currency since the 10 February shipment. The ABNC replied that they had not and on 25 August asked for an example of the bogus notes but the bank replied, on 2 September, that they were all in the possession of the U.S. authorities in New OrleansABNC, folder 259, Banco de Jalisco (1907-1932).

Leslie Hendriks, the Resident agent in Mexico City, took advantage of the situation to write an article for the Mexican Herald and this appeared on 4 November 1910. However, Hendriks wrote to the New York office that the printed article was scarcely in the form in which he had asked that it should appear. “I presume they thought my article was too palpable an ad. and so cut it.”ABNC, folder 259, Banco de Jalisco (1907-1932).

As a postscript we should note that a set of front and back printing plates (measuring 8½ by 15 inches) and 15 sheets of uncut notes (59 notes in all) from this counterfeit issue were put up for auction by a lady in Philadelphia on eBay in January 2002 and sold for $2,429. By now most of the sheets have probably been cut up into singles.