Counterfeit sábanas

The sábanas were widely counterfeited. They were an emergency issue, in circulation within a few days of being conceived and using typefaces and edging designs that were to be found in hundreds of printing presses. The first mention of forged sábanas was on 17 March 1914, three months after they were put into circulation, and thereafter it is a constant theme. References suggest that up to 25 per cent of the notes in use were bogusFifty per cent of a consignment of $2,000 sent from Durango to Torreón were judged to be forged. (ADU, Sección de Hacienda, p178, telegram Governor Saravia to Villa, 17 November 1914). Twenty-five per cent of the cash in the Tesorería General del Estado in Aguascalientes was false (Periódico Oficial, 27 February 1915).. Experts travelled throughout northern and central Mexico examining notes but even some counterfeits were mistakenly revalidated for further circulation.

Genuine twenty-five centavos sábanas were still being printed in July 1915 so they had a longer lifespan than originally intended and forgeries were still being produced in June 1915.

The information on counterfeits comes from a variety of sources:

(a) circulars and official correspondence,

(b) newspaper and court reports of counterfeiting, and

(c) examination of the notes themselves, particularly those overprinted 'FALSO'.

Occasionally the differences appear actually to be merely variations between two genuine issues: for instance, $10 note without ‘x’ seems to be so common that either most surviving notes are bogus or the officials picked on a distinction between legitimate varieties. Similarly, the ‘No. No.’ rather than ‘No. Núm.’ mentioned in the Parral cases is a legitimate variety. It is obvious that any official, and even more so any member of the general public, when faced with a well-handled, dirty, creased note and with perhaps only a limited knowledge of these distinguishing characteristics, many of which were relative terms such as thicker paper or darker ink, could be forgiven for not being able to recognise the genuine article. If in doubt, it was safer to refuse them. The result was a growing reluctance to handle any sábanas and increasing strident attempts by the authorities to force their acceptance.

Circulars

We have copies of various pronouncements on identifying forgeries and can devise a matrix of the different features that were used, at various times, to distinguish the counterfeit from the genuine notes. These include

(a) a circular from the Tesorero General of Chihuahua, dated 21 March 1914, following a review of notesPeriódico Oficial, Chihuahua, 22 March 1914

(b) a notice from the comisionado especial in Ciudad Juárez, Baltasar Anaya, dated 24 March 1914

(c) a notice from Parral, dated 6 November 1914, listing new differences noted

(d) a notice published in December 1914

(e) a shorter notice published in December 1914

(f) a variant of the above, reissued in February 1915, and

(g) instructions issued by the Tesorero General of Sonora, around December 1914.

In March 1914 photographs of the genuine Villista currency were put in circulation so people could compare their notes, and a regulation established by which all notes paid in to government offices for taxes had to be endorsed on the back by the person using them, as with a chequeEl Paso Herald, 20 March 1914: Albuquerque Journal, 21 March 1914: Prensa, 26 March 1914. Also in March 1914 governor Manuel Chao decreed the death penalty for those having in their possession counterfeit Constitutionalist money. The decree was promulgated in Ciudad Juárez, through the distribution and posting of handbills. It stated that persons arrested with counterfeit money in their possession would be given a trial and offered an opportunity to show that they were innocent purchasers. Failure on their part satisfactorily to explain the possession of the bogus fiat money would be followed by executionEl Paso Herald, 27 March 1914.

Correspondence

On 17 March 1914 Villa's financial agent, Lazaro de la Garza, wrote to Chao that since notes had been issued both with Chao’s signature stamped in rubber and also printed in steel, it was very difficult to know if there were counterfeit notes. He did not believe that there were any counterfeits but acknowledged that if the public offices refused to accept notes it would cause great panic and lack of confidenceLG Papers, 3-C-10, telegram from de la Garza, Ciudad Juárez, to Chao, Chihuahua, 17 March 1914. On 19 March Lazaro de la Garza asked Chao to send someone with samples of the various state issues so that they could have a telegraphic conference on the subjectLG papers, 3-C-13, telegram L. de la Garza, Ciudad Juárez, to Chao, Chihuahua. 19 March 1914 and two days later he met with the heads of the public offices in Ciudad Juárez to study some notes and decided that in counterfeit notes:

(a) the typeface was thicker

(b) the comma was missing after the word ‘válido’

(c) the red of the numbering was clearer (mas clara)

(d) the Tesorería seal was printed in metal

(e) the $50 note had less rays in the shaded letters

(f) (on the $50) there was an ‘n’ in place of the first ‘u’ in Chihuahua

(g) (the $50) had an ‘h’ instead of ‘b’ in ‘Diciembre’.

They decided that in order to recover public confidence the Agencia would revalidate and sign good notes and that they would publish the characteristics of the counterfeit notesLG Papers, 3-C-14, telegram from de la Garza, Ciudad Juárez, to Chao, Chihuahua. 19 March 1914 (‘…tener los falsificados el tipo de letra mas grueso, falta la coma después de la palabra “válido”; ser la tinta roja de los números mas clara; y estar sellados con sello metálico, además los de 50 pesos tiene menos rayos las letras sombreadas; en vez de la primera “u” en la palabra Chihuahua tienen un “n”, y una “h” en vez de una “b” en Diciembre,…’). However, the first notice, issued on 21 March, mentioned only a couple of these characteristics.

On 19 March 1914 the Tesorería General del Estado sent a telegram to the Recaudador de Rentas in Parral advising about couterfeit sábanas. The forgeries could be identified by the following characteristics:

(a) larger type

(b) completely black ink

(c) edges joined at the corners

(d) printed seal of bronze

(e) Chao’s signature ended in a point or ball (punto ó bola)

(f) point in front of Vargas’ signature is lowerAMP, Tesorería, Tesorería, Correspondencia, caja 165, exp. 1.

On 22 March 1914 Silvestre Terrazas, in Ciudad Juárez, wrote to the Governor of Sonora with some points of difference so that he could in turn inform the civil and military authorities. These differences were small but discernable, particularly:

(a) that the counterfeit used a metal Tesorería seal on the reverse, whilst genuine notes had a hand-stamped rubber seal

(b) counterfeit notes were printed by lithography or photoengraving and so did not have the slight breaks that true printed notes did

(c) the black print in the counterfeit notes was a little coarser

(d) on the counterfeits the end of Chao’s signature had too strong a mark

(e) on the counterfeits the first dot of Vargas’ signature was a little higher than on the genuine

(f) the colour of the counterfeits was a little more intense

(g) the counterfeit had ‘Gobernado’ rather than ‘Gobernador’

(h) the counterfeit had ‘Imp’ without a commaAGHES, Fondo Oficialidad Mayor, tomo 2993, telegram Silvestre Terrazas, Ciudad Juárez, to Governor, Sonora 22 March 1914 (‘…Se distinguen los billetes falsos de los legítimos en pequeñas pero visibles diferencias: primeramente el sello que llevan al reverso está mejor hecho en los falsos que en los verdaderos porque en estos está puesto con sello de goma, a mano y en los falsos está impreso con sello metálico. El marco de los billetes falsos se ve de un solo pieza sin las ligeras desuniones que corresponden siempre a las placas de imprenta cuyos ajustes nunca son enteramente perfectas como casi lo es en los billetes falsos por haberse hecho seguramente en litografía ó en fotogravado la impresión en gral del negro en los billetes falsos es un poco mas grueso que en los verdaderos, seguramente por el transporte c[olmo] sellama en términos técnicas por los litógrafos. Las firmas de los billetes falsos tienen también una seña especial en la del gral Chao cuya firma tiene un punto demasiadamente marcada en la extremidad de la rubrica y en la del tesorero Gral resulta también el primero punto antes de la firma, un poca mas arriba como esta en los billetes verdaderos. Hay otros pequeñas detalles que teniendo a la vista uno y otro billete pueden distinguirse con relativa facilidad, viéndose también que el color de los falsos es un poco mas fuerte que el de los legítimos y algunas palabras de los falsos como gobernador no esta completa y dice solamente “Gobernado” al pie de imprenta en lugar de decir imp. dice “Imp” en la palabra valida, los billetes falsos carecen de una coma, que tienen los legítimos y así otros detalles…’).

On 9 June 1914 Lazaro de la Garza wrote to Villa and Governor Avila that a very fine counterfeit version of the $5 sábanas had appeared, with the only difference being that the peso sign in the counterfeits had two strokesLG Papers, 1-F-28, telegram from de la Garza, Ciudad Juárez, to Villa, Torreón and Fidel Avila, Chihuahua, 9 June 1914. This is counterfeit type 4. Avila replied that he had again written to Carranza and his Subsecretario de Hacienda for the eight million in Constitutionalist notes (emisión nacional) so that they could replace the sábanasLG papers, 3-D-24, telegram Avila, Chihuahua, to L. de la Garza, Ciudad Juárez, 11 June 1914.

Newspaper and court reports

On 24 March 1914 Felix Prieto was arrested in Chihuahua for trying to pay for drinks in the cantina Saturno with two counterfeit notesAlmada, roll 810, 2379 Presidente Municipal Interino, Chihuahua to Juez 1º de lo Penal while in April Genaro Flores was released after being accused of circulating counterfeit notes for lack of evidenceAlmada, roll 810, 3043 Presidente Municipal Interino, Chihuahua, to Juez 1º de lo Menor en funciones del 1º de lo Penal 14 April 1914.

On 26 March the Douglas Daily Dispatch reported that several hundred thousand pesos in counterfeit Villa notes had appeared in Cananea and Nacozari. The bad money had first surfaced in El Paso and Ciudad Juárez, a shipment of five million pesos having arrived from New York, and between one and two million pesos had been brought to the border between Douglas and Nogales. The workmanship was said to be perfect, and in several ways superior to the genuine Villa issueDouglas Daily Dispatch, 26 March 1914, so these were likely to be notes with the metal Tesorería seal.

In April 1914 two American employees of the Alvarado Mining and Milling Company, in Parral, were arrested for passing counterfeit money. This case is detalled in The counterfeits from the Alvarado Mining and Milling Company.

Aso in April 1914 the Supreme Court in Chihuahua recorded a number of cases concerning counterfeits $20 notes that were circulating in Ciudad Guerrero. Surprisingly, the investigators seem to have been extremely fair in trying to find the source of the notes but recognising that the people arrested for passing them (including Chinese) had acquired them in innocenceASTJC, cases núm. 37, 39, 41 and 42 from Ciudad Guerrero, April 1914. The details were:

| Case number |

Date | Holder(s) | Value | Series | No | Experts (peritos) |

| 37 | 31 March 1914 | Jesús Torres | $20 | A | 1807 | Alberto Pons and Jesús José Caraves |

| 38 | 18 April 1914 | Librado Rico | $20 | A | 6159 | Victor Ayub and Carlos B. Azar |

| 41 | 1 April 1914 | Antonio Luis and Adolfo Domínguez | $20 | A | ||

| 42 | 2 May 1914 | Fernando Chávez | $20 | A | 7166, 14520 | Victor Ayub and Carlos B. Azar |

Between May and September 1914 a number of people in Hidalgo del Parral were accused of counterfeiting after passing forged sábanas. These cases are detailed in Other counterfeits from Parral.

In July 1914 a Huertista newspaper reported that the Constitutionalists in charge of the presses had been printing extra currency for their own account. When Villa had discovered this he had sentenced the counterfeiters and anyone suspected of counterfeiting to death but they had fled to the United States. Villa tried to have them tried before an American court but the judge ruled that as Villista currency was not recognised by the American authorities as legal tender no crime had been committedEl Independiente, 2 July 1914.

A new flood of counterfeit sábanas appeared in Ciudad Juárez in August 1914El Paso Herald, 11 August 1914.

In December 1914 a Guadalajara newspaper reported a counterfeit $5, with the legend ‘Gobernor del Estado’ instead of ‘Gobernador del Estado’, and a counterfeit $10, with the background in pale green (verde palído) rather than the genuine bright blue (azul fuerte). Moreover, on the right of the genuine notes the blue edging was slightly separate from the black square, whilst in the forged notes it was the same on all four sides. Finally the $10 note was a worse impressionBoletín Militar, Guadalajara, 11 December 1914 ‘…Además en la parte derecha de los billetes buenos, la guarda azul esta ligeramente separada del cuadro negro que guarda la relación del billete, cosa que no sucede en los falsificados, los cuales guardan simetría en los cuatro lados. Por último, la redacción de los billetes falsoficados de a diez pesos no está perfectamente derecha y se nota desde luego que ha sido impreso en una pésima imprenta…’.

For incidences of arrests and prosecutions for counterfeiting Villista money in the United States see Counterfeiting in the United States.

Incidences of Americans arrested in Mexico for possessing counterfeit Villista currency

Since reports usually referred to counterfeit 'Villista money' they could refer to sábanas or the later dos caritas.

On 11 March 1914 a Mexico City newspaper reported that a Villa agent had arrested a Texan with $100,000 in counterfeit notes in his briefcase. He was taken to prison in Ciudad Juárez, to await Villa’s instructionsEl País, 11 March 1914.

Mrs. Virginia Mendez: In July 1914 Mrs. Mendez from Santa Fe, New Mexico, was detained by the Constitutionalist authorities in Ciudad Juárez and accused of having $500 of counterfeit Villista currency in her possession, but later releasedEl Paso Morning Times, 14 July 1914; El Paso Herald, 18 July 1914.

George Morrow: In August 1914 George Morrow, a Ciudad Juárez merchant, was offered a package of $3,000 in $10 Villista notes by Raoul Ramiz, who had purchased the money from a firm of El Paso money brokers in good faith and actually been given a written guarantee. Morrow said the money was false, so Ramiz took them to local Ciudad Juárez officials, who declared them counterfeit and stamped them “false”El Paso Herald, 25 August 1914.

J. O. Robb and Frank James: Robb, of El Paso, and Frank James, aka George Boise, were arrested in Ciudad Juárez on 22 August 1914 charged with passing counterfeit Constitutionalist money. It is charged that, when arrested, Robb had $200 and Boise $500 in counterfeit notes upon their persons. Robb claimed that the money was given to him in change after he made a purchase in a Ciudad Juárez store and that he was unaware that it was counterfeitEl Paso Herald, 24 August 1914: El Paso Herald, 27 August 1914. They were tried in the customs house in Ciudad JuárezEl Paso Herald, 28 August 1914 but the mayor of El Paso, C. E. Kelly, managed to obtain Robb's releasePrensa, 3 September 1914. In fact, they were passing counterfeit money that they had obtained from Dr. A. S. Bronson.

In September 1914 the mayor of El Paso, C. E. Kelly drew attention to the fact that 63 Americans had been arrested in Ciudad Juárez, accused of passing counterfeit notesPrensa, 3 September 1914.

Later reports, on Joseph Kleinman, Minor Meriwether, George Marx, Samuel Finkelstein, Mrs. F. E. Arerdes and John Amos, are listed in the section on counterfeit dos caritas whilst W. B. Cox appears in the section on counterfeit Monclova notes.

Mexicans arrested in Mexico for possessing counterfeit money

F. A. Ruiz: Ruiz, a customs broker in Ciudad Juárez, whose family lived in El Paso, was arrested in March 1914 on a charge of passing counterfeit rebel money. His friends said he has been held without a hearing and that if he had passed any counterfeit rebel money, it was done innocently, as there is almost as much counterfeit money in circulation as genuine in Ciudad JuárezEl Paso Herald, 24 March 1914.

Policarpo Suso: a Spanish subject, formerly Spanish vice consul at Torreón and manager of the Compañía Agrícola de Río Bravo, Suso was arrested at Matamoros, Coahuila, on 17 April 1914 on a charge of circulating counterfeit currencyAlbuquerque Journal, 18 April 1914, but these were of the Monclova issueOn 28 May the Jefe de Hacienda in Matamoros, Dr. Luis G. Cervantes, wrote to General Pablo González in Monterrey, that many Monclova notes in the six different denominations had appeared, with numbers greater than 500000 and different signatures using the same signatures as Suso’s notes. He wanted to know if they were genuine, since customs did not want to accept them and they were causing a panic (APGG). By June 1914 the American consul, Jesse H. Johnson, had managed to get Suso released from jail but on condition that he did not leave MatamorosPrensa, 18 June 1914.

Manuel Pérez: on 19 January 1915 police arrested a Manuel Pérez in Mexico City with 29 counterfeit $10 sábanas that he claimed he had received from the “La Unión” store. The differences were:

(a) the black edging line was stronger in the counterfeit than in the genuine notes,

(b) the small line of the borders was continuous in the counterfeit notes and broken in the genuine notes (en los extremos de la orla se puede ver en los buenos, una pequeña línea que la separa, mientras en los falsificados se ve corrida la línea en cuestión), and

(c) the counterfeits were of better quality paper with heavier inkingEl Monitor, 20 January 1915 ‘…Se distinguen los billetes buenos de los malos, en los siguientes detalles: desde luego, en la orla que en línea negra circunda el billete, en los buenos, se ve la tinta más débil que en los falsos; y además de esto, en los extremos de la orla se puede ver en los buenos, una pequeña línea que la separa, mientras en los falsificados se ve corrida la línea en cuestión. La clase de papel, es otro detalle de suma importancia para distinguir unos de otros. En los legalmente emitidos, la clase de papel es de menor calidad que la de los malos, observándose en estos más cuerpo en el papel así como la impresión general, es más fuerte en tinta…’.

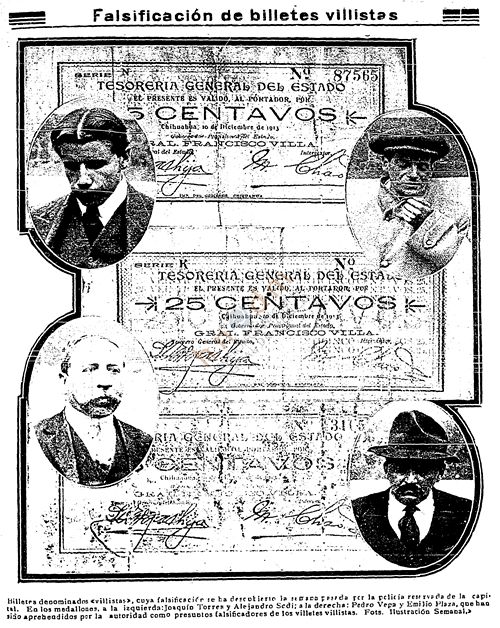

Joaquín Torres, Pedro Vega, and Adolfo Angeles: The Mexico City police asked an engraver how counterfeiters would acquire the necessary plates without exposing themselves, and were told that they would probably not order them all at one time but as various different pieces, to be assembled later. So they visited different print workshops and in January 1915 arrested Andrés López, the owner of one such workshop in calle de Victoria 58, and his sister, Juana, after they found some suspicious plates, that resembled the edging of sábanas. The sister told the police that an individual, who had not left his name but frequently visited the shop, had ordered the plates. The police lay in wait and, some days later, detained Alejandro Sodi, a member of one of the city’s most distingushed familiesAlejandro Sodi was already under surveillance and the subject, on 28 November 1915, of a report from three agents of Pablo Gonzalez’ secret police (Alvaro B. Gómez, Luis Ontiveros and Agustín Reverter) in Veracruz. Sodi was from Oaxaca, a newspaperman and brother of Porfirio Díaz’ Minister of Justice who on Madero’s election, left for Havana, Cuba, and New York, and then back to Cuba, his lifestyle being funded by Porfiristas. He lodged at the Hotel Diligencias in Veracruz and associated with Louis Federik Thomsson, brother of a counterfeit of constitutionalist paper money who had escaped from arrest in Veracruz. The two Thomsson brothers had been involved in passing counterfeit notes (of Obregón and Luis Caballero issues) in Tampico, Tamaulipas. Sodi had been involved in printing anti-Constitutionalist tracts in Veracruz and during the American occupation produced a reactionary newspaper, El Norte.The agents were keeping all these people under surveillance (document provided by Angel Smith). After the Revolution Sodi was one of the leaders of a small political party, the Confederation of Unions of the Middle Class (Confederación de Sindicatos de la Clase Media) that “pursued the true and effective betterment of the Mexican middle classes” and supported Calles. According to a letter written on 23 October 1924 by E. Ogarrio to President Obregón, Alejandro Sodi had faced charges and jail for falsifying money and being a swindler in 1915 (AGN, Ramo Presidencial, Grupo Álvaro Obregón y Plutarco Elías Calles 307-S-33), and Emilio Plaza.

Joaquín Torres, Pedro Vega, and Adolfo Angeles: The Mexico City police asked an engraver how counterfeiters would acquire the necessary plates without exposing themselves, and were told that they would probably not order them all at one time but as various different pieces, to be assembled later. So they visited different print workshops and in January 1915 arrested Andrés López, the owner of one such workshop in calle de Victoria 58, and his sister, Juana, after they found some suspicious plates, that resembled the edging of sábanas. The sister told the police that an individual, who had not left his name but frequently visited the shop, had ordered the plates. The police lay in wait and, some days later, detained Alejandro Sodi, a member of one of the city’s most distingushed familiesAlejandro Sodi was already under surveillance and the subject, on 28 November 1915, of a report from three agents of Pablo Gonzalez’ secret police (Alvaro B. Gómez, Luis Ontiveros and Agustín Reverter) in Veracruz. Sodi was from Oaxaca, a newspaperman and brother of Porfirio Díaz’ Minister of Justice who on Madero’s election, left for Havana, Cuba, and New York, and then back to Cuba, his lifestyle being funded by Porfiristas. He lodged at the Hotel Diligencias in Veracruz and associated with Louis Federik Thomsson, brother of a counterfeit of constitutionalist paper money who had escaped from arrest in Veracruz. The two Thomsson brothers had been involved in passing counterfeit notes (of Obregón and Luis Caballero issues) in Tampico, Tamaulipas. Sodi had been involved in printing anti-Constitutionalist tracts in Veracruz and during the American occupation produced a reactionary newspaper, El Norte.The agents were keeping all these people under surveillance (document provided by Angel Smith). After the Revolution Sodi was one of the leaders of a small political party, the Confederation of Unions of the Middle Class (Confederación de Sindicatos de la Clase Media) that “pursued the true and effective betterment of the Mexican middle classes” and supported Calles. According to a letter written on 23 October 1924 by E. Ogarrio to President Obregón, Alejandro Sodi had faced charges and jail for falsifying money and being a swindler in 1915 (AGN, Ramo Presidencial, Grupo Álvaro Obregón y Plutarco Elías Calles 307-S-33), and Emilio Plaza.

Under interrogation Plaza said that the plate had been made by Adolfo Angeles, in a workshop located in the calle del Cinco de Mayo; that Joaquín Torres had rented the premises at calle del Apartado 15, where counterfeit sábanas were produced, and that Pedro Vega, owner of the bar on the corner of calles Tacuba and Mariscala, had put up the money for the operation. Angeles learnt that he was being sought and escaped, but Torres and Vega were arrested and sent to the sixth precinct (sexta comisaria)La Opinión, 27 January 1915.

The magazine La Ilustración Semanal had a picture of the counterfeits, including 25c sábanas series N and K (single No., large numbers)La Ilustración Semanal, Año II, Núm. 70, 2 February 1915.

The magazine La Ilustración Semanal had a picture of the counterfeits, including 25c sábanas series N and K (single No., large numbers)La Ilustración Semanal, Año II, Núm. 70, 2 February 1915.

Manuel Otero: Otero, a native of Durango, was executed in Ciudad Juárez on 26 March 1915 after he had been convicted of smuggling counterfeit Mexican money into Mexico. He was arrested that afternoon at the International bridge and 50,000 pesos in counterfeit money found concealed in his clothing. He attempted to bribe the inspector at the bridge with 3,000 pesos to gain his release, but was unsuccessful and an immediate trial and execution followedAlbuquerque Journal, 28 March 1915.

Salamon Nigri and Rafael Fereze: These two Syrians were executed at Torreon on 30 March 1915 for possessing counterfeit Mexican money. The two merchants had shown their money to the Villista officials who had declared it good. Shortly after, soldiers arrested them in their stores and shot them without delayAlbuquerque Journal, 2 April 1915.

Pablo Wong: The Chinese Wong was apprehended on 31 March with $1,000 hidden on his left leg, $500 on his right, $104 at his waist and $370 in his wallet, only the last being genuine. At his home the authorities found the clichés and other tools. The notes were of the Estado de Chihuahua, though probably sábanas. He was summarily sentenced to death by the Comandancia Militar and executed on 6 April in the grounds of Santa RosaVida Nueva, 8 April 1915. SD papers 312.93/102 Consul Marion Letcher to State Department, 9 April 1915.

Humberto Paniaguet et al.: on 26 May 1915 an attempt by the police and troops to apprehend counterfeiters in the calle del Ferrocarril de Cintura, Colonia de la Bolsa, Mexico City, resulted in a firefight in which two people, Manual Paniaguet and Carlos Gómez, were killed. The police arrested Humberto Paniaguet, his mother María Trinidad Gómez, Rafacia Medina and Faustina Bello and found a press for printing cartones and notes, numerous typefaces, boxes of red and black ink, and a revalidation seal, very similar to the one used by the Tesorería de la Federación. The notes were counterfeit sábanasThe Mexican Herald, 28 May 1915.

Francisco Oviedo and Rafael Marín: On 28 May Colonel Sebastián W. Miranda, Lieutenant Colonel Luis Rodríguez and Captain Luis Zamora, arrested Francisco Oviedo and Rafael Marín for circulating false currency. They were taken to the Cuartel General del Sur and then to the District Government, together with two women who accompanied them and who appeared to be innocent. Oviedo and Marín were in possesion of some perfectly counterfeit sábanas, with counterfeit revalidation stamps, as well as more than ten pesos in bogus 20c cartones. The prisoners claimed that the counterfeit notes had been given to them in a jewelry store and the cartones in a cantina. The District Government sent the four defendants to jail, placing them at the disposal of the competent judgeThe Mexican Herald, Año XX, Núm. 7,203, 29 May 1915. Oviedo shared his name with someone (the same?) who had been arrested in December 1914 for counterfeiting Banco Minero de Chihuahua notes..

J. Félix Arévalo, Leonardo Macillas, Pedro y Ceferino Silva: In June 1915 four people, Leandro Mancillas, Pedro Silva, Ceferino Silva and Subteniente J. Felíx Arévalo, were publicly executed in Aguascalientes for counterfeiting Chihuahua paper currencytwo on 10 June (Prensa, 23 June 1915). In addition to 610 false 25c notes and some other counterfeits, the authorities recovered two clichés, ink and a “Tesorería General del Estado. Chihuahua” seal. The notes were poor imitations, particularly the 25c notes which could be recognised by the state of the reverse seal‘La falsificación de los dichos billetes está burdamente hecha, pues ni el color de la tinta, la clase del papel y demás detalles se parecen en todo a los auténticos, sobre todos los de veinticinco centavos, los que bien pueden ser reconocidos como falsos por lo mal hecho del sello, que está impreso al reverso’. (AAG, caja 12-B, exp. 17; Vida Nueva, 13 June 1915; 14 June 1915).

Juan N. Ríos: Also in June the police discovered a factory turning out Carvajal bonds, sábanas, cartones and stamps at 183, 3ª (or 5a) calle de Altamirano in the suburb of Tacubaya, Mexico City. They found cameras and photographic and printing equipment, chemicals and paper. The sábanas and cartones were equal or superior to the ones that were being accepted by the banks and the public as genuine. The police found just 96 $50 sábanas in one of the toiletsEl Renovador, 3 July 1915, The Mexican Herald, 29 June 1915 reported that Subteniente Rafael Galván discovered cliches for $50 sábanas and 10c and 20c cartones. It also gives the address as 792, calle de Altamirano. The group was producing sábanas, even though they had been withdrawn from circulation, as they intended to hand them in in exchange for other notesEl Combate, 1 July 1915.

Having recovered the materials the police set a watch on the house and arrested Pedro Mata, who claimed just to be a cleaner for the owner, Juan N. Ríos, but was held as an accomplice. Ríos himself had fledEl Combate, 2 July 1915.

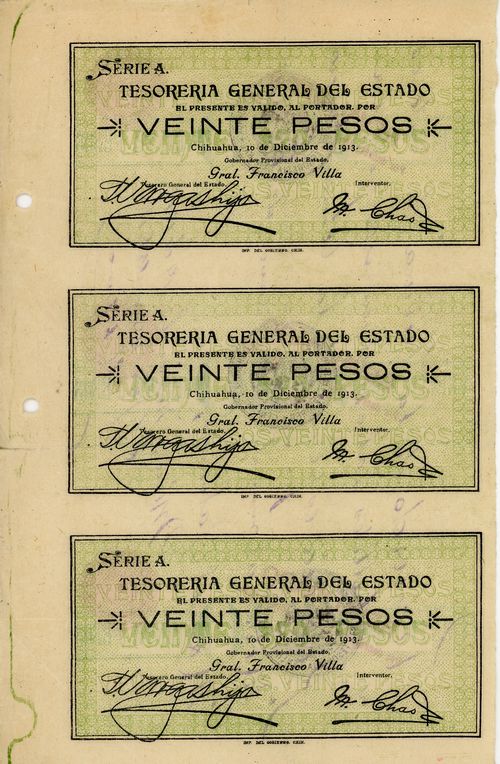

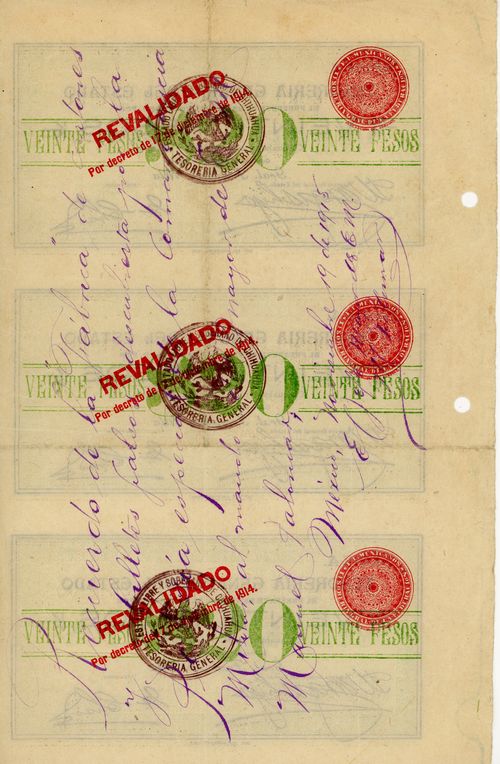

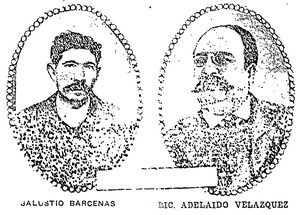

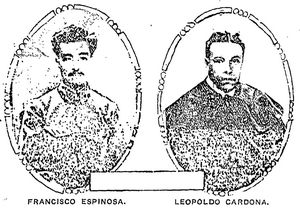

Salustio Bárcenas, Leopoldo Cardona, Francisco Espinosa, and Adelaido VelázquezAdelaido Velázquez was a 52-year-old lawyer, living at 3a calle de la Violeta no. 63; Leopoldo Cardona, a 33-year-old businessman, living at 4a calle de Lerdo no. 124; Salustio Bárcenas, a 32-year-old printer, living at callejón de Niño Perdido no. 24; and Francisco Espinosa, a 24-year-old deaf-mute litographer, from Zamora, Michoacán, living at 2a calle de Cocheras no. 70: These were arrested by the Policía Especial de la Comandancia Militar, along with their equipment and false currency (cartones and sábanas), and confessed their crime. They had been involved in a plant for bottling wine and so acquired the press and other lithographic equipment needed to print labels, but from mid-1913 had found it more productive to produce cartones and notes.

Velázquez, Cardona and Bárcenas were sentenced to death, Espinosa to ten years imprisonment. Bárcenas and Velázquez were shot in the Escuela de Tiro on the morning of 13 November. Cardona escaped from his prison in the main gate of the Palacio Nacional, whilst under the watch of teniente Felipe Acevedo. Teniente Acevedo y cabo José Aguilar were shot for allowing him to escapeEl Pueblo, 13 November 1915.

We know of an uncut sheet of three $20 sábanas with the inscription “Recuerdo de la fábrica de cartones y billetes falsos descubiertos por la Policía especial de la Comandancia Militar, al mando del Jefe mayor de E. M. Manuel Palomar, / México, Noviembre 19 de 1915 / El Jefe Mayor de E. M. / M. Palomar”. This no doubt refers to this fábrica.