Early issues

For a discussion on the tienda de raya see this Introduction in the Chihuahua section. Although it was against the law mining companies, haciendas and larger factories seem to have paid most of their wages other than in legal tender. Much of this will have been as credit, or with personalised chits or with metal tokens (fichas), so paper currency will have been a smaller subset. Nonetheless, it is likely that the list of establishments offering what can be classified as “paper money”, from the 1860s through to the 1920s, would be quite sizeable if the evidence had been retained.

In the meantime, we should document any references that we find.

La Metalúrgica

The mines of Asientos and Tepezalá and the foundry of La Metalúrgica were the property of Franco Parkman. In the mines and smelter the company had established a tienda de raya where the workers were either paid in merchandise, or with fichas that were only for internal useEl Fandango, 26 July 1896. Information from Vicente Ribes Iborra, La reforma y el porfiriato en el estado de Aguascalientes, Madrid, 1981. The Mexican workers were paid, at least nominally, two reales a day, but the tienda did not give out a single centavo in legal tender, only vales. In its first 20 days of operation in 1896 the tienda had a daily turnover of $1,633.60, more than any other store in the city which complained that their business had dropped in halfEl Fandango, 23 August 1896. As it had a guaranteed clientele and was also exempt from state taxes the tienda was bound to be a cash cow for the businessEl Fandango, 26 July 1896.

A newspaper article in April 1898 described La Metalúrgica as a kind of Republic of San Marino (the enclave in Italy) with its own laws, police and jail, where the workers were forced to work by the armed police. It also, like Roberto Camarena infra, used its own paper currency to pays its employees but, though accused of the same crime as Camarena, it had not been fined. The court, governor Rafael Arellano and the public prosecutor were apparently powerless to correct this abuseLa Patria, Año XXII, Núm. 6433, 15 April 1898.

La Gran Fundición Central Mexicana

The Gran Fundición Central Mexicana in 1905

This smelter was established by the Guggenheims in 1895 and became the largest employer in the state.

According to the Diario del Hogar it paid its workers with vales which they were compelled to spend in the tienda de raya, where it had a monopoly. It also discounted the vales and provided expensive and shoddy goodsDiario del Hogar, 28 March 1897{/footmote}.

In March 1897 Ignacio Ríos é Ibarrola (or Ignacio Ruiz Ibarrola) denounced the company to the authorities. The company argued that the vales could not be called paper money (papel moneda)La Voz de México, 21 March 1897 : El Diario del Hogar, 28 March 1897, presumably claiming that they were advances on wages and any outstanding wages were paid out on the regular payday.

A year later the same abuse was still being reportedLa Voz de México, 16 March 1898 and then in September 1898 it was claimed that few were willing to work in this dangerous works because it paid 50c a day in paper money only redeemable in the tienda de raya for goods at prices twice as much as normal. Apparently the company was thinking of bringing in a thousand ChineseLa Patria, Año XXII, Núm. 6562, 22 September 1898.

Conversely, in 189[ ] the manager of the Grand Fundición Central informed the state governor that most workers would be paid daily, and "for this reason the tienda de raya was no longer important." As a result, the tienda would henceforth only hold those items that were strictly necessary and that the workers who live on the smelter's grounds neededAHEA, Fondo Secretaría General de Gobierno, caja 9, exp. 43 .

In 1901 the smelter became part of ASARCO.

La Hacienda “Cañada Honda”

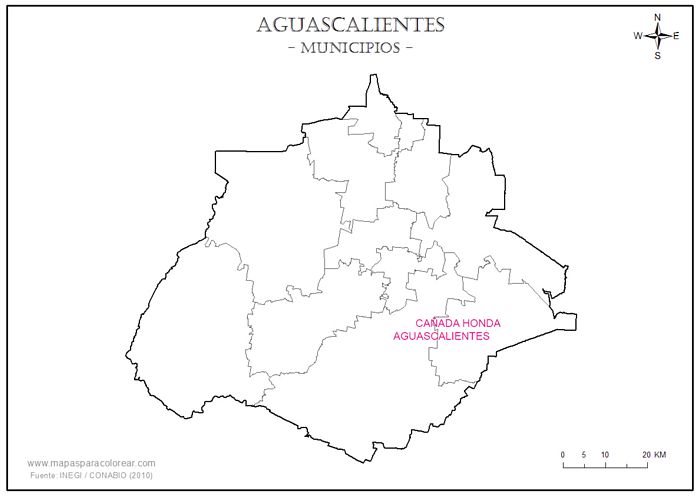

This hacienda of 6,000 hectares is situated 22 kilometres north-east of Aguascalientes.

Roberto Camarena, the owner, created his own paper issue to pay his workers. In November 1896 some youths stole (some of) this money, and Camarena locked them up. Based on this, Camarena was accused of a crime and imprisoned himself, though not in jail but in the military barracksLa Patria, Año XX, Núm. 6026, 26 November 1896. In March 1897 he was sentenced to a large fine and a month in jail for paying with valesEl Diario del Hogar, 28 March 1897.

The next year the hacienda passed from the Camarenas to José León García.