Mining companies

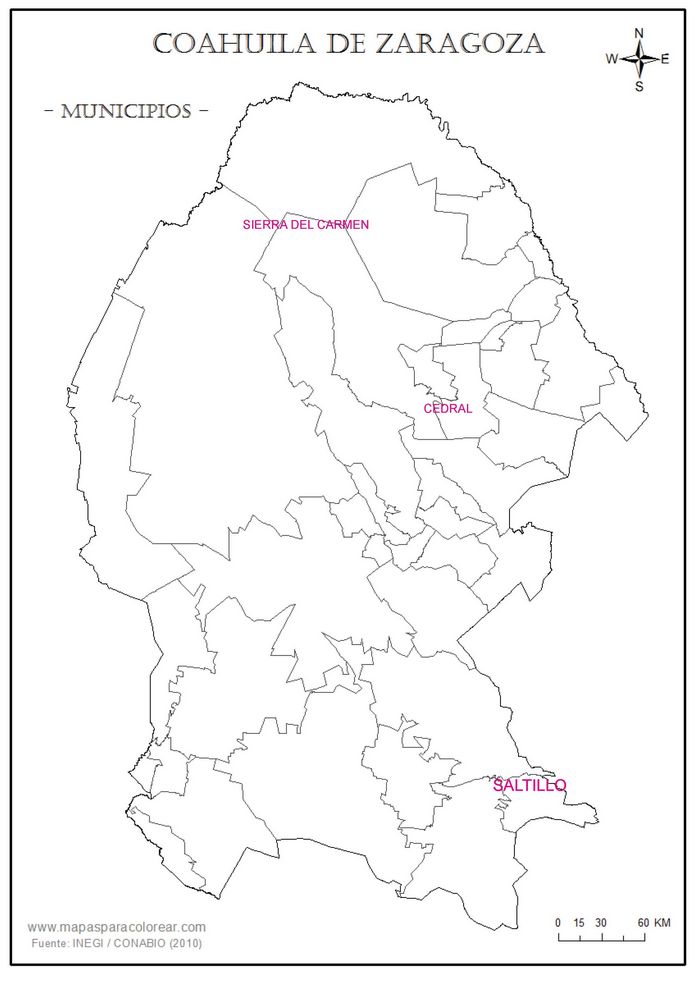

Sierra del Carmén

Sierra del Carmén

The Sierra del Carmén, also called the Sierra Maderas del Carmén, is a northern finger of the Sierra Madre Oriental in the state of Coahuila. The Sierra begins at the Rio Grande at Big Bend National Park and extends southeast for about 45 miles (72km), reaching a maximum elevation of 8,920 feet (2,720m).

Mina la Fronteriza

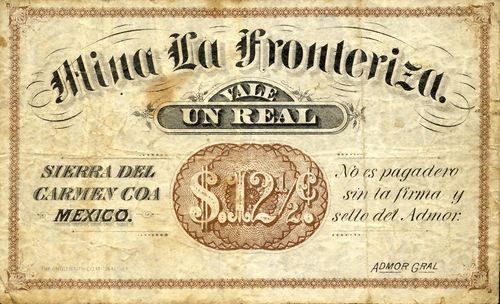

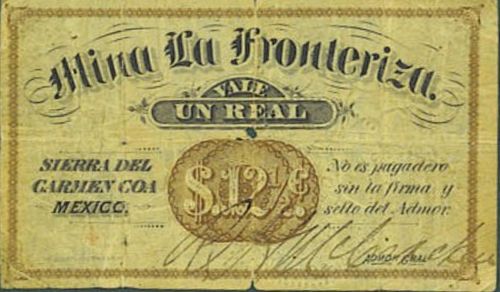

M681 1r/12½c Mina La Fronteriza

M681 1r/12½c Mina La Fronteriza

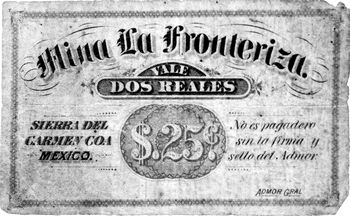

M682 2r/25c Mina La Fronteriza

M682 2r/25c Mina La Fronteriza

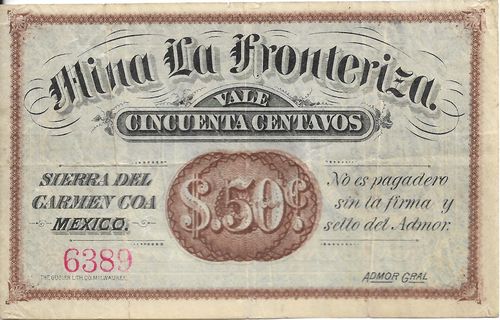

M683 50c Mina La Fronteriza

M683 50c Mina La Fronteriza

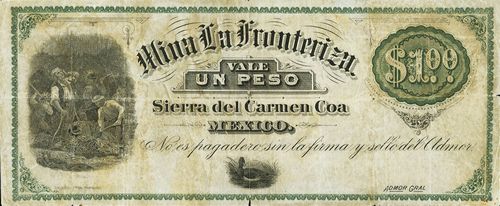

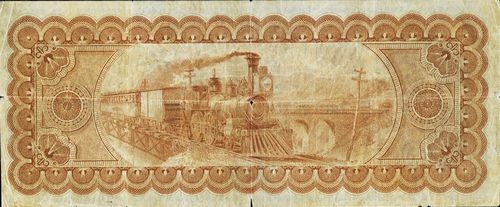

M684 $1 Mina La Fronteriza

M684 $1 Mina La Fronteriza

| from | to | total number |

total value |

||

| 12½ c/1 real | |||||

| 25c/2 reales | |||||

| 50c | includes number 6389 | ||||

| $1 | |||||

A series of notes in both the real and the decimal system (12½ centavos/1 real, 25 centavos/2 reales, 50 centavos/4 reales[image needed] and 1 peso). These notes were printed by the Gugler Lithographic Company of Milwaukee, WisconsinThis printing company was started by German immigrant Henry Gugler (1816-1880) and his two sons, Julius (1848-1919) and Henry Jr. (born 1858). Julius went to Milwaukee in 1869 and worked first for Seifert & Lawton, Lithographers. Henry moved to Milwaukee in the early 1870s and joined the firm, which soon became Seifert, Gugler & Co. In 1878 the firm changed to H. Gugler & Sons. By 1883 it had 55 employees and handled all advertising for Pabst Brewing.

Further information possibly lies in the Gugler Lithographic Company Collection in the Milwaukee County Historical Society Research Library and Museum, in particular box 2, folders 26 to 27A and box 3 folders 28-28A (bond and stock certificates and notes); box 3 folder 29-31 (checks engraved by Gugler Co.), and box 3, loose (bond and stock certificates and notes (in packs) and checks engraved by Gugler Co (in packs)).

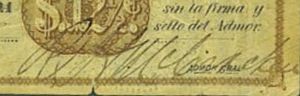

M681 1r/12½c Mina La Fronteriza

M681 1r/12½c Mina La Fronteriza

The 12½ centavos/1 real note is known signed by the Administrador General, R. Mc[ ][identification needed].

|

The Mina “La Fronteriza” was sold to an English company for $300,000El Siglo Diez y Nueve, 1 March 1888. In 1896 “La Fronteriza” mine belonged to the “Compañía Jesús María” and was leased to the Kansas City Smelting y Cía.

Cedral

The Cedral Mine

The Mississippi San Rafael Silver Mining Company and its successors were modest-sized, U.S.-based corporations that operated the Cedral mine from 1870 through the early 1890s. During that time the mine yielded around 50,000 tons of silver-lead ore, but failed to yield a profit for its owners, a shifting group of shady promoters and respectable businessmen. The proximity of the border made it possible for smaller, less well-financed companies to enter the Mexican market and the Mississippi San Rafael Silver Mining Company and its successors provide an example of a failure that was as historically significant as success.

The Cedral was the most famous silver mine in the Santa Rosa mining district, located in Coahuila about 100 miles south of Eagle Pass, Texas. The rock that surrounds the mine is hard but porous limestone through which runs an enormous vein of silver-lead ore. Most of this ore is too low in metal content to repay the cost of extracting and refining it, but scattered throughout are numerous pockets of valuable ore. These “pay streaks” lured miners into the Cedral throughout its long history.

The original owners of the Cedral were Jesuit missionaries but in 1770 the mine was denounced by Juan Ignacio de Castillo and it remained in his family for the next century. By 1866, because of mounting difficulties and the political chaos, nearly all work had been suspended in the mines around Múzquiz and in 1870, two Texans, John H. Harris and Jules A. Randle, purchased the Cedral mine from Don Jesús Castillo. Early in 1871 the pair secured a charter of incorporation from the state of Mississippi for the Mississippi San Rafael Silver Mining Company. Having formed their company, Harris and Randle prepared an over optimistic prospectus which attracted $500,000 from investors. However, when Harris and Randle were unable to deliver the promised rewards, they were forced out of the company and a new board of directors took over.

The new president was Abraham Murdock, a wealthy merchant with long experience in business and politics. However, the Cedral continued to fail to show a profit and the shareholders began demanding changes. In 1875, Murdock hired Alfred Wurtweiler, “a scientific and practical metallurgist and smelter,” to rectify the situation. At first Wurtweiler was successful and for a short time it appeared that the Cedral would prove to be the bonanza that investors had expected. However, three basic problems - a lack of adequate transportation, the quality of the ore, and mismanagement - would eventually frustrate the company’s efforts. Late in November 1875, after arguments between Wurtweiler and the mine’s manager, Williams, Murdock went to the mine to see what could be done. He fired Williams but failed to coax Wurtweiler to return. With his superintendent and his chief engineer gone, Murdock decided to stay and supervise the mine himself despite his lack of experience with either mining or Mexico.

Murdock simply relied on the poorly paid native miners to work the richest ore in sight. Since he did not bother to timber the tunnels that were dug, cave-ins cost the lives of miners and threatened to ruin the workings. Finally, heavy rains flooded the mine and brought the work to a complete halt. After four years in Mexico, even Murdock realized that the Cedral could not be worked without professional management and a substantial infusion of money.

In 1880 a group of Mobile investors formed the Cedral Mining and Smelting Company to supply the money needed. The new company was almost indistinguishable from the old Mississippi San Rafael Silver Mining Company. Augustus Winston, president of the National Commercial Bank of Mobile and a former member of the San Rafael Company’s board, became manager of the Cedral mine. Later he served as president of both companies. On at least two occasions, representatives of both companies met together to make joint decisions. The only significant difference between the old company and the new one was that Murdock was no longer president.

Armed with the financial resources of the new Cedral company, Winston began to take steps to make the mine a modern enterprise. Timber was installed in the mine and smelting ovens were built. A long-neglected coal mine nearby was reopened and the coal made it possible to use a larger array of machines. Four new boilers provided steam to run an engine that powered water pumps, fans, and an air compressor that provided power for several pneumatic drills. Tracks for ore cars were laid from the head of the mine to the coal mine and the smelting works. Although not all the efforts were successful, the company had no difficulty locating subscribers for its stock at least through the summer of 1881.

The cost of modernizing the mine, however, proved greater than the rewards of increased silver output. In April 1884, Winston, as president of the National Commercial Bank of Mobile, accepted $46,500 worth of Cedral stock as collateral for a bank loan to the company. The penny-pinching Murdock was brought back as manager to reduce expenses. Despite these efforts, work was suspended for lack of funds in the spring of 1885 as the mine was still not profitable.

At this low point, local politics intruded. The jefe político of nearby Múzquiz joined four members of the prominent Galán family in denouncing the Cedral as an abandoned mine. Murdock was away at the time, but his representatives there appealed to the U.S. consulate for assistance. The consul fired off a sharp note demanding respect for the rights of the Cedral’s owners, but his protests had no effect. On 30 November 1885, the property on which so much U.S. energy and capital had been expended passed back into the possession of Mexican nationals.

The takeover of the Cedral claim by the Galans and their allies did not prove to be an unmitigated disaster for all of the mine’s former owners. Murdock saw it as an opportunity to win greater control of the mine and reduce its financial burdens. Since the denouncement had extinguished all prior titles, the Cedral was no longer encumbered by the need to pay dividends to the stockholders of the Cedral and Mississippi San Rafael companies. He cautiously approached two of his business associates, Winston and John Bowen, a Mobile businessman, with the proposition that they repurchase the mine from the Galans and operate it as a partnership until they could sell it at a price that would compensate them for their earlier losses.

Murdock returned to Mexico and repurchased the Cedral mine for $3,600. He then oversaw the resumption of operations personally, abandoning all efforts to smelt ore, and confining himself to operations he felt competent to direct. Even so, his difficulties continued. The mine was worked at a deeper level than before and this entailed constant pumping to drain the water that seeped in. He tried using brush from the surrounding countryside as fuel for the boilers, but the wood was too green to burn properly. His solution was to reopen the Cedral coal mine even though this necessitated a lengthy diversion of the work force. But the coal burned at too high a temperature for the antiquated boilers, so Murdock had to order a new boiler from San Antonio. In early 1888 Murdock reported that extremely heavy rains had washed out the roads and impeded work. He had built up a good supply of coal, but the unremunerative work had put him“behind on his finances” and he feared that he might need to draw on his partners for additional funds to pay for the new boiler or just to meet the payroll. Despite their problems, Murdock was determined to keep the work going. At the end of January his persistence paid off as he struck a sizable vein of good ore. By late spring the mine was producing about $1,000 worth of silver a month.

Bowen and Murdock were not fated to enjoy their success. In late 1887 the boards of directors of the Cedral company and the Mississippi San Rafael Company insisted on a share of the proceeds from any sale of the mine. In reply, Bowen argued that the 1885 denouncement had extinguished their titles to the mine so that the Cedral now belonged exclusively to the new partnership. The miners finally agreed that the machinery and buildings at the Cedral still belonged to the old companies and that arbiters would divide the proceeds whenever the mine was sold.

Bowen died in January 1888, leaving his estate to three minor grandchildren, and Murdock died in Eagle Pass while on his way back to Mobile to seek additional funds for improvements to the mine, leaving the Torreys, Bowen’s successors, in complete charge of the Cedral. Despite their efforts, the mine produced very little silver and in June 1891 was leased to the large firm of Guggenheim’s Sons. The Guggenheims gave the Cedral mine the most intensive working it ever had and by 1893 the Cedral was one of the most thoroughly and efficiently worked mines in Mexico.

However, ongoing problems, a fall in the price of silver and disputes with, and squabbles between, the Cedral’s owners led the Guggenheims in March 1894 to announce their intention to quit the Cedral and return it to the owners. For a large concern like the Guggenheims, the abandonment of the Cedral was a brief setback. For the Cedral’s owners, however, it was the final blow.

So, two companies, the Mississippi San Rafael and the Cedral, lost their entire capital. Several investors - Winston, Bowen, the Torreys, and the Guggenheims - squandered thousands of dollars on the mine to no apparent profit. Murdock had spent the last years of his long and productive life in a vain effort to retrieve his investment in the mine. Such failures were far more typical of U.S.-owned mines than the successes touted by promoters.

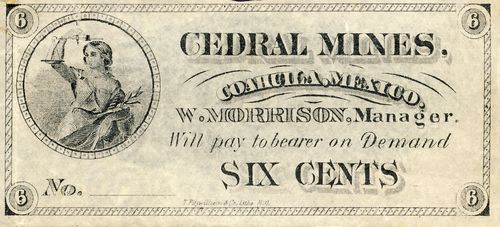

M680 6c Cedral Mines

M680 6c Cedral Mines

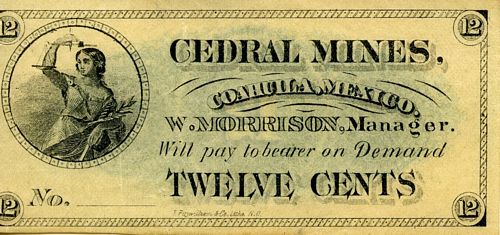

M680.2 12c Cedral Mines

M680.2 12c Cedral Mines

Of the three known notes, the first two are for six and twelve cents. These might seem strange denominations but they hark back to the real system, where eight reales equaled one peso and so a half real (medio real) was six and a quarter centavos. These notes bears the name of W. Morrison, as Manager. They were printed by T. Fitzwilliam & Co. Ltd., Manufacturing Stationers, Lithographers and Printers, of 324, Camp Street, New OrleansThomas Fitzwilliam came to New Orleans from Ireland and in the 1860s began a printing establishment that by 1872 was producing lithography. With the demise of the Southern Lithographic Company about 1885, Fitzwilliam had a near monopoly in the field of lithography in New Orleans.

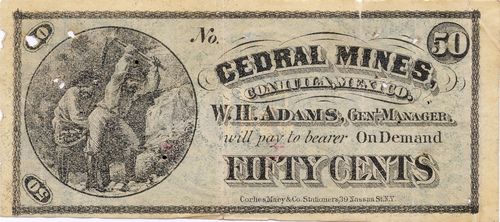

M680.5 50c Cedral Mines

M680.5 50c Cedral Mines

The third note is for fifty cents. This bears the name of W. H. Adams as General Manager and so can be dated to around 1882. The note was printed by Corlies, Macy & Co., Stationers, Printers, Lithographers and Account Book Manufacturers, of 39 Nassau Street, New York.

A remarkable feature of these notes is that they are only in English. Were they exclusively for use by the American miners and did they mean to refer to American cents rather than Mexican centavos, in which case they would be worth twice as much as one Mexican peso was roughly equivalent to fifty U.S. cents.

(Based on "The Cedral Mine, Coahuila" by Elmer Powell, USMexNA journal June 2016)

Jimulco

Jimulco is situated in the municipality of Torreón.

In March 1911 a newspaper reported that labourers in some of the haciendas around Jimulco, especially one that was well known and had absentee owners, were paid not in cash but in vales, only valid in the hacienda’s tienda de raya, so the workers could not buy goods for less at other stores. The workers were hoping for the owners’ return as, being just and well-intentioned, they would end this abuseEl País, 22 March 1911. As Alexander Pope wrote, hope springs eternal in the human breast.