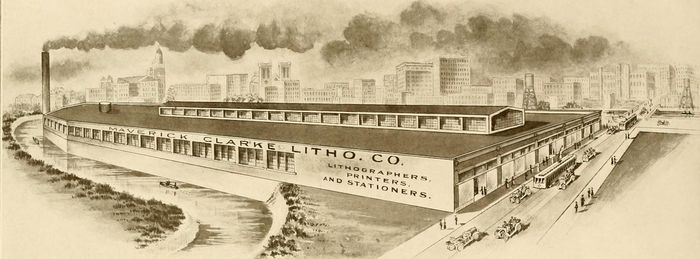

Maverick-Clarke Litho Company, San Antonio, Texas

On 13 February 1914 Lázaro de la Garza, from the Hotel Sheldon, El Paso asked the American Bank Note Company for a quote for 500,000 50 centavos; 750,000 one peso, 200,000 five pesos 150,000 ten pesos, 37,500 twenty pesos and 15,000 fifty pesos Chihuahua State Treasury notesSo, an original total of $5,000,000. On 28 February 1914 it was reported that Chao was to buy silver bullion of $3,000,000 gold to be used as the basis for a new issue of paper currency (The Mexican Herald, 1 March 1914). They were to have two small portraits on the front and a photograph of a building on the back, one signature facsimile and two secret marksABNC. The next day the ABNC replied that they regretted that they could not quote. In an internal memo they explained that as they understood that the state of Chihuahua was in the hands of rebels, they took it for granted that it was they who wanted the money and it was against the company’s principles to print money, stamps, etc., for a revolutionary governmentABNC. So de la Garza had to look elsewhere, and the first issue of dos caritas was in fact printed by the Maverick-Clarke company in San Antonio, Texas.

This company dated back to 1874, when Samuel Maverick, a pioneer Texan and signer of the Texas Declaration of Independence, established the Maverick Printing Company. Robert Clarke, a prominent businessman, then bought a controlling interest and changed the name to Maverick-Clarke. The business flourished and expanded into the manufacture of the county record books, paper boxes, bank cheques and forms and also sold office supplies and furniture. Sales were made in San Antonio and throughout the state by travelling salespeople or ‘drummers’ travelling over the railway network. The company established a solid reputation for quality and specialized in jobs requiring fine detail and craftsmanship. In 1914 the company was based at The Office Man’s Department Store, 125-129 Soledad, San AntonioThe president was W. E. Milligan and secretary and treasurer, Ned McIhenny. Unfortunately Maverick-Clarke's records were lost when the company moved premises in the early 1940s.

On 24 March a contract was signed with Maverick-Clarke to produce 5,000,000 pesos in various denominations. On 8 May the San Antonio ExpressSan Antonio Express, 8 May 1914. Ferlas was José F. Farías was able to report:

Adding $5,000,000 to the volume of the circulating medium of the Mexican Constitutionalists, the Maverick-Clarke Litho Co. yesterday completed the huge task of lithographing 1,652,500 pieces of currency ranging in value from 50 cents to 50 pesos. Contract for the big job was executed at Juarez, March 24, it being stipulated that the last of the bills was to ready by midnight Monday night. The final number of the hundreds of thousands of pieces of the currency was finished at 8 o’clock, four hours ahead of the required schedule.

Agents of the Constitutionalists, Jose Ferlas (sic) and Senor Gonzales, paid the contract price yesterday in gold coin of the United States and the plates were turned back to the Carranza government. They were delighted with the work and complimented the lithographers and others who had aided in the completion of the program they were sent here to supervise.

The issue is divided as follows: Five hundred thousand 50 cent pieces, 750,000 1 peso bills, 200,000 5 peso bills, 150,000 10 peso certificates, 37,500 in twenties and 15,000 in fifties. Throughout the weeks the contract was under way a double guard of Maverick-Clarke watchmen was maintained about the establishment by both the company and the Constitutionalists. That part of the shop where the lithographing was being done was roped off from the rest. Every one of the pieces of paper had to be accounted for.

Paper used in the making of the money that is worth at least a fourth of its face value in United States cash, and will rise materially in value if the Constitutionalists succeed, consists of what is known as Woronoco parchment. It is not only strong and flexible, but resists use and wear and tear equal to any currency made in any Government establishment.

Watchful care over the manufacture of the money did not cease with the work of the lithographers. As the bills were finished, they were stored carefully in metallic caskets. As one was filled it was sealed and soldered. Under heavy guard these steel receptacles were taken to the border. Not even President W. E. Milligan of the Maverick-Clarke Company knows where its guard went with the money.

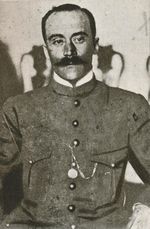

Before it can be put into circulation, however, it will have to be signed by both the tesorero general and the interventor. It is presumed this will be done at Chihuahua. The signature of M. Chao, lately deposed as Governor of Chihuahua by orders of General Villa, is lithographed upon all the currency contained in the issue.

Contract for the work was signed by L. de la Garza, as the representative of the Constitutionalists. He sent a dozen or fifteen men to San Antonio to act in various capacities while the lithographing was being done. Extreme care was taken by all these men to prevent any publicity in connection with their mission.

Messrs. Ferlas and Gonzales left to the firm doing the work the matter of selecting the designs. These are conceded by all who have seen samples of the currency to be very handsome. The new money is pretty. Every piece save those of the 50-centavo size bears excellent likenesses of the men whose memories are revered by Constitutionalists: the two martyrs, Francisco I. Madero and Abram Gonzales. Gonzales was the Governor of Chihuahua, who is said to have been murdered by being hurled from a train on which he was a prisoner under the moving wheels.

On the reverse side is a splendid reproduction of the National Palace in the City of Mexico, guarded at either side by a huge griffin. On the front, etched between the photographs of Madero and Gonzales, are these words: "El Estado de Chihuahua. Pagara. Al Portador en Efectivo. Conforme al Decreto Militar de Fecha. 10 de Febrero de 1914. Chihuahua, Chihuahua, Mexico."

On the opposite side of the cinquenta centavos pieces is the coat of arms of the Mexican Republic, supplemented by these words, "Gobierno del Estado Libre y Soberano de Chihuahua." Scrollwork adorns both ends of every piece of currency. Men familiar with such matters say it will be an absolute impossibility to ever successfully counterfeit any of this currency.

This is the first money known to have been lithographed in this city. The Constitutionalists have had so much trouble in the way of having their currency lithographed that every precaution that could possibly have been taken was used in connection with the issue manufactured for them here. Of late there have been scores of counterfeits of the various denominations issued by them. Millions of an issue consigned to them a year or so ago was held up at the border, the affair ending in litigation in the United States Courts.

Though nobody connected with the contract seems to have any idea as to the point on the Rio Grande where the money was taken for crossing, Constitutionalists said last night the currency was already over the river and that the task of signing it will be on in a day or two.

The money was shipped from San Antonio to El Paso on 9 May for forwarding to Ciudad Juárez and TorreónEl Paso Morning Times, 9 May 1914. The report says there was six million dollars in Constitutionalist money and $5,000,000 in Constitutionalist postage stamps.

To recap, the notes were:

| Number | Total value | |

|---|---|---|

| 50c | 500,000 | 250,000 |

| $1 | 750,000 | 750,000 |

| $5 | 200,000 | 1,000,000 |

| $10 | 150,000 | 1,500,000 |

| $20 | 17,500 | 750,000 |

| $50 | 15,000 | 750,000 |

| 1,652,500 | $5,000,000 |

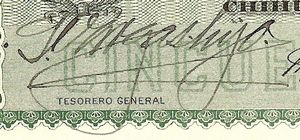

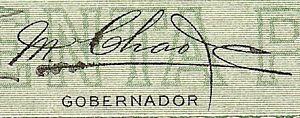

As the newspaper report stated, the notes were printed with the central signature already engraved on the plate. The very earliest notes had the other two signatures hand-written but they were soon applied by machine, except for the 50 pesos which always has two hand-written and one printed signature. The three signatories are Sebastián Vargas hijo as Tesorero General, Manuel Chao as Gobernador and J. M. Muñoz as Interventor.

Sebastián Vargas came from a liberal family, as his father was a deputy in Abraham Gonzalez’ legislature of 1912. He was born in Ciudad Juárez, and held the post of Recaudador de Rentas there in 1911 and 1912. After Huerta’s coup d’état he joined the Junta Constitucionalista in El Paso, and wrote to Carranza on 2 June 1913 offering his services and asking for a jobCEHM, Fondo XXI, carpeta 3, legajo 339. Villa appointed him State Treasurer (Tesorero General del Estado) of Chihuahua on 9 December 1913 and he held the post until 21 August 1915, when he was arrested by the Carrancistas on capturing the cityHe was replaced by Máximo L. Portillo. Sebastián Vargas came from a liberal family, as his father was a deputy in Abraham Gonzalez’ legislature of 1912. He was born in Ciudad Juárez, and held the post of Recaudador de Rentas there in 1911 and 1912. After Huerta’s coup d’état he joined the Junta Constitucionalista in El Paso, and wrote to Carranza on 2 June 1913 offering his services and asking for a jobCEHM, Fondo XXI, carpeta 3, legajo 339. Villa appointed him State Treasurer (Tesorero General del Estado) of Chihuahua on 9 December 1913 and he held the post until 21 August 1915, when he was arrested by the Carrancistas on capturing the cityHe was replaced by Máximo L. Portillo. He subsequently retired from politics and died in 1946. |

|

Manuel Chao was born in 1883 in Túxpan near Tampico. When he was seventeen his father took him along on a trip to Durango. He decided to stay, taking a teaching post in Durango, and later taught in several towns in Chihuahua. He also supplemented his wages by setting up a shop along the railway yard near the town of Baqueteros, Chihuahua. He took up arms for Madero in 1910 and in 1912 organised a ‘Regimiento Hidalgo’ of irregulars to fight against Orozco but when Huerta usurped the presidency he led his regiment into revolt and seized control of the south of the state. Manuel Chao was born in 1883 in Túxpan near Tampico. When he was seventeen his father took him along on a trip to Durango. He decided to stay, taking a teaching post in Durango, and later taught in several towns in Chihuahua. He also supplemented his wages by setting up a shop along the railway yard near the town of Baqueteros, Chihuahua. He took up arms for Madero in 1910 and in 1912 organised a ‘Regimiento Hidalgo’ of irregulars to fight against Orozco but when Huerta usurped the presidency he led his regiment into revolt and seized control of the south of the state.Carranza considered Chao to be the best of all the Chihuahuan revolutionary chiefs, more educated and socially acceptable than the rest and seemly more in tune with Carranza’s own ideas and orders. In late September 1913 Chao met with other revolutionary chiefs gathered at Ciudad Jiménez to plan the attack on Torreón. Carranza recommended the election of Chao as the overall leader but the others chose Villa. When Chao attempted to assert his authority Villa faced him down and Chao with his brigade retired to Parral. Chao helped Villa in his attack on Chihuahua. The two seemed to have no difficulties in co-operating in military matters but whenever a political question arose Carranza favoured Chao and was often openly disdainful of Villa. When Villa’s División del Norte occupied Ciudad Chihuahua Carranza instructed that Chao be named provisional governor of the state. Villa ignored Carranza and named himself governor and Chao returned to Parral. However, after the defeat at Ojinaga on 31 December 1913, Villa realised that he could best serve as a military commander and resigned as provisional governor on 7 January 1914, turning the office over to Chao. However, Villa was still annoyed so when he returned to Chihuahua in mid-April, without consulting Carranza, he ordered Chao as his military subordinate to take command of his troops and depart for Torreón. Chao ignored the order, whereupon Villa ordered his summary execution. Carranza, however, countermanded the order and confirmed Chao as governor. He resigned the post in May because of disagreements with Villa. He later served as governor of the Federal District, and then as governor of Guanajuato (January 1915). Chao lost his life for supporting de la Huerta in 1923. |

|

|

J. Manuel Muñoz was the foreman of Silvestre Terrazas’ newspaper, El Correo. By February 1915 Muñoz was using headed notepaper that showed him to be a ‘Comerciante y comisionista’ in Durango. and at that time was acting as the Jefe de HaciendaADur, Fondo Secretaria General de Gobierno (Siglo XX), Sección 6 Gobierno, Serie 6.7 Correspondencia, caja 6, nombre 62. After Villa was defeated, Muñoz emigrated to the United States and worked as a printer for the Newspaper Printing Corporation in El Paso for more than 26 years before he retiredEl Paso Herald-Post, 5 September 1955. He died on 17 November 1971El Paso Times, 19 November 1971. |

|

Chao’s signature was engraved on the plate so not changed, even though he was no longer governor.

On 12 May Carranza’s Tesorero General, Serapio Aguirre, sent Carranza a telegram from Ciudad Juárez suggesting that, in order to stop speculation in these dos caritas it was necessary to take drastic action, such as suspending their circulation, arranging their withdrawal and instructing all finance offices (oficinas recaudadores) to refuse themCEHM, Fondo MVIII, telegram Aguirre, Ciudad Juárez, to Carranza, Durango, 12 May 1914. On Villa’s part, Lázaro de la Garza felt that to prevent counterfeits (and incidentally to ensure Carranza’s backing for the new issue) it would be useful to validate the dos caritas with the machine that was being used to validate the Ejército Constitucionalista notes and on 14 May Silvestre Terrazas wrote asking for Carranza’s permission. The same day Carranza told de la Garza that Pani had one machine ready and soon there would be two moreLG papers, 9-A-20, telegram from Carranza, Durango, to de la Garza, Ciudad Juárez. 14 May 1914. Carranza gave his consent on 16 MayCEHM, Fondo MVIII , telegrams Terrazas, Chihuahua, to Carranza, Durango, 14 May 1914: Carranza, Sombrete, to Terrazas, Chihuahua, 16 May 1914 and on 22 May told de la Garza that the sealed notes were to replace the earlier issue that was too easily counterfeitedLG papers, 9-A-21, telegram Carranza, Durango, to de la Garza, Ciudad Juárez, 22 May 1914. On 22 May de la Garza complained that the revalidation had yet to start, but Pani explained to Carranza that they were still validating the $5 Ejército Constitucionalista notes. Since the $1 Ejército notes had yet to arrive, once they had finished the $5 notes, they could dedicate three machines to stamping the Chihuahua notesCEHM, Fondo MVIII, telegrams de la Garza, Ciudad Juárez, to Carranza, Durango, 22 May 1914: Pani, Ciudad Juárez, to Carranza, Durango, 23 May 1914. On 10 June Pani reported that they expected to finish stamping the Chihuahua notes that day, just as the $1 Ejército notes were finally deliveredCEHM, Fondo MVIII, telegram Pani, Ciudad Juárez, to Carranza, Saltillo, 10 June 1914, though de la Garza reports that some notes still had not been stamped by 18 JuneLG papers, 1-F-63, de la Garza, Ciudad Juárez, to Villa, Torreón, 18 June 1914. De la Garza reports that in the Oficina Reselladora were 80,000 stamped and 420,000 unstamped $1 notes, and 20,000 stamped $5 notes that were faulty and were going to be returned to the printers, the rest having been sent to Chihuahua as ordered. In the Agencia Financiera there were another $50,000 in notes for stamping but they lacked a stamping machine..

So Carranza believed that he was authorizing Villa to issue six million pesos to take out of circulation the sábanas that were being widely counterfeitedEl Liberal, 25 October 1914.

On 18 June 1914 de la Garza suggested to Villa printing a second issue of at least ten million using the same printers, again using Chao’s signature (though Fidel Avila was now governor), to replace the sábanas which were being better and better counterfeitedLG papers, 3-D-36, telegram de la Garza, Ciudad Juárez, to Fidel Avila, Chihuahua. 18 June 1914. Villa agreed the following dayLG papers, 1-F-64, telegram Villa, Torreón, to de la Garza, Ciudad Juárez, 18 June 1914 and LG papers, 3-D-40, telegram Alfredo S. Farias, Ciudad Juárez, to Fidel Avila, Chihuahua. 19 June 1914.

Though it was generally understood that the return by Villa of all the new Carranza currency that he had seized at Ciudad Juárez was for the express purpose of putting that money in circulation and retiring all other issues, the El Paso Herald reported on 9 July that an agent of Maverick-Clarke had been in the city for a few days negotiating for what was said to be a large new issue of Villa money. If this happened, it opined, one of the most important settlements of the Torreón conference would be practically nullified and Villa’s return of the Carranza money would mean nothingEl Paso Herald, 9 July 1914. However, the Villistas were talking to other printers and chose to move to the Norris Peters Company, in Washington, D.C., which was already printing the Ejército Constitucionalista notes.

Maverick-Clarke had ordered extra paper, in anticipation of another order, and in October 1914 had a correspondence with de la Garza over responsibility. Luckily the paper mill was willing to take back the stock and de la Garza agreed to pay the incidental expensesLG papers, 4-G-7, letter from Maverick-Clarke, San Antonio, to de la Garza, New York, 10 October 1914: 4-G-8: 4-G-10. On 23 October 1915 Maverick-Clarke sued Villa in the 41st district court for $10,261 for stationery which it had printed for him (El Paso Herald, 23 October 1915)..

The San Antonio Express report says that the Maverick-Clarke plates were handed over to de la Garza’s agents and on 17 June de la Garza reported that he had themLG papers, 1-F-56, unidentified telegram, 17 June 1914 and two days handed them over to Ignacio Perches EnriquezLG papers, telegram L. de la Garza, Ciudad Juárez, to F. Avila, Chihuahua, 18 June 1914: 1-F-67, telegram L. de la Garza, Ciudad Juárez, to Villa, Torreón, 19 June 1914. However, they were certainly used again to produce further notes (see the second Norris Peters printing), and Maverick-Clarke employees were later accused of counterfeiting, so their future history is as yet unclear.

On 13 October 1914 the Villistas applied for U.S. patents for the design of these dos caritas as a way of protecting them from counterfeiters LG papers, 1-F-114, telegram from de la Garza, New York, to Villa, Chihuahua. 13 October 1914. Certain patents were granted in February 1915Patent 47028 of 2/3/1915 underprint reverse of note

Patent 47029 of 2/3/1915 underprint front of note

Patent 47030 of 2/3/1915 text front of note

Patent 47031 of 2/3/1915 reverse of 50c

Patent 47032 of 2/3/1915 text front of 50c note

Patent 47033 of 2/3/1915 underprint front of 50c note (LG papers, 4-F-8).