Haciendas

The state of Jalisco seems to have been the most prolific in producing private issues during the revolution, particularly for use on haciendas, despite the fact that the revolutionary governor, Manuel Aguirre Berlanga, on 7 October 1914, in his decree núm. 39 regulating labour and establishing a mínimum wage, stated that salaries had to be paid in legal tender and banned the use of vales and the tienda de raya. Because of the shortage of coinage, it became a case of "Needs must".

The state of Jalisco seems to have been the most prolific in producing private issues during the revolution, particularly for use on haciendas, despite the fact that the revolutionary governor, Manuel Aguirre Berlanga, on 7 October 1914, in his decree núm. 39 regulating labour and establishing a mínimum wage, stated that salaries had to be paid in legal tender and banned the use of vales and the tienda de raya. Because of the shortage of coinage, it became a case of "Needs must".

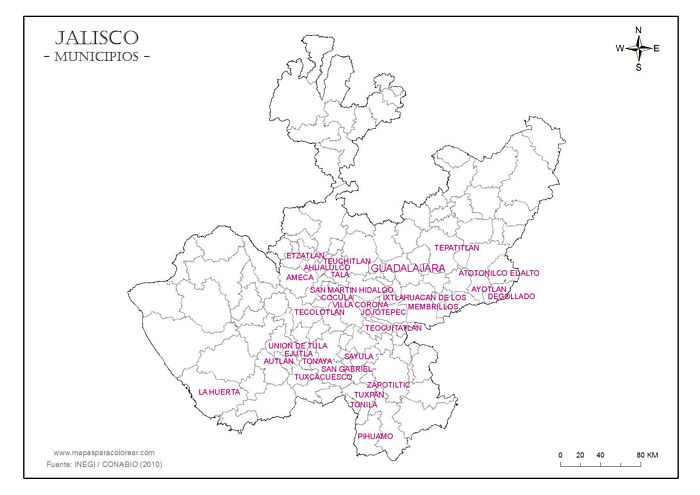

The different types of workers is explained in the following description of the Bellavista hacienda, in the municipalities of Acatlán de Juárez and Tala Sergio Valerio Ulloa, “La hacienda de Bellavista durante la revolución” in Estudios Jaliscienses, 82, November 2010.

By 1910 this hacienda was owned by the company Hijas de Remus Sucesora and comprised three farms called El Plan, Navajas and Bellavista. The farms had a total area of 24,200 hectares, of which 1,900 hectares were arable, and of these only 400 hectares were irrigated. The rest were mountain and pasture lands; low-quality land that was not suitable for agriculture but was where the cattle of the same hacienda grazedAGN,. Caja de Préstamos. Caja 52, vol. I, Acta de la Sesión del 15 de febrero de 1909.

Bellavista also owned three factories that produced sugar, alcohol, and mezcal, respectively, with machinery introduced since the 1980s and by 1910 that was already considered outdated and obsolete. However, the Bellavista hacienda had a value of 1,300,000 pesos and produced an annual income of 97,000 pesosibid..

Together, Bellavista, El Plan, and Navajas made up a hacienda complex that combined agriculture, livestock, and industry in a single property. In this way it obtained different agricultural products: sugar cane, corn, beans, wheat, coffee, sweet potato, chickpeas, mezcal, barley and honey. It also raised different kinds of livestock: cattle, mules, horses, goats and pigs, while in its factories it made sugar, panocha, alcohol and tequila. Far from being an autarkic hacienda, to a large extent its products were aimed at satisfying the demand of the regional market – especially that of Guadalajara – and some of these were sent to the national market, mainly sugar.

To exploit the different areas of this hacienda, its owner, María de Jesús Remus, through her administrator, established different types of labour relations with her workers. Some were the permanent labourers who lived all year round in the housing of the hacienda. They received a payment in cash (jornal) and another in kind (ración), which varied according to the activity and hierarchy of the worker or employee; however, on average the first was 36 centavos per day, and the second 3 litres per day of corn. These workers also received a small plot of land where they could plant their own corn and beans, or other types of vegetables, or raising farm animals that complemented their daily diet. They could also access credit from the tienda de raya, where they could buy other products for their consumption that were not produced on the farmSergio Valerio Ulloa. “El Plan y Las Navajas. Libros de contabilidad en dos haciendas jaliscienses (1920-1922)”. Gladys Lizama Silva (coord.). Historia regional. El centro occidente de México: siglos XVI al XX. Guadalajara: Universidad de Guadalajara, 2007, pp. 141-178..

The number of permanent or housed (acasillados) labourers was actually a minority with respect to the total number of workers needed throughout the year on the hacienda. The permanent workers who occupied the hacienda were 300 on average and were dedicated to various tasks such as repairing fences, carrying firewood, taking care of the cornfield and the cane fields, milking cows and taking care of the cattle. On the other hand, according to the needs of the agricultural cycles, in certain seasons such as sowing and harvesting, the demand for agricultural workers greatly increased, so that during the harvest the number of workers could reach up to 3,000. For this, temporary workers were hired, who were in charge of carrying out very specific tasks such as cutting cane or harvesting corn, and once their task or the season was over, they were fired and rehired in the following seasonAGN. Caja de Préstamos. Caja 52, vol. I, Informe del administrador general Francisco de la Cruz, 19 de marzo de 1911.

These temporary workers received the same payment in kind and in money as the farmhands, but they did not have a house to live in with their family, nor credit in the tienda de raya nor a plot of land where they could plant their vegetables or raise their animals. With no other ties to bind them, most of these temporary workers were residents of towns near the Bellavista hacienda, such as Acatlán de Juárez, Tizapanito or Villa Corona, San Marcos, Santa Catarina, Los Pozos, La Resolana and Ahuisculco, from which they left at dawn for the hacienda and returned at sunset. The vast majority of these neighbours did not have land or had one or two hectares that did not give them enough to live on, or to support their families, so they were forced to leave their village and look for work on the neighbouring haciendasArchivo del Registro Agrario Nacional (ARAN). Expedientes de los Ejidos de Tizapanito (Villa Corona), Acatlán de Juárez, San Marcos, Los Pozos y Bellavista.

From these towns also came another type of workers who used the Bellavista hacienda: the medieros, who planted corn and beans on the poor quality lands that the landowner lent them. These workers established a very particular type of relationship with the owners of the hacienda since they divided the harvest obtained in half. In spite of this, all the advances and loans that the landowner had made were deducted from the half that corresponded to the mediaro, so that in the end the mediero had a third or quarter of the harvest left. By 1921 the Bellavista hacienda had approximately 500 medierosAGN. Caja de Préstamos, vol. 82, Hijas de Remus Sucra. Reparto de tierras y bueyes para siembra de maíz por medieros en el año de 1921..

Another type of Bellavista workers were the workers of the sugar, alcohol and mezcal factories, who also received a cash salary and a ration of corn as payment. Their number also depended on the agricultural cycle of the sugarcane, since during the harvest time up to 625 workers could work in the factories and in the rest only 300. Their salary varied in relation to their trade, specialty and hierarchy, and on average they earned more than farm workers: their salary was around 50 centavos and they were given 4 litres of corn a day as a rationAJ, T-3-922. Caja T-20, Oficios de los trabajadores del ingenio y del gerente, Enrique Remus, 30 de agosto de 1922..

Thus, there was great complexity in the internal functioning of the Bellavista hacienda and in its labour relations. Despite the difficult situations it faced in the late 1900s-1910s, Bellavista was considered by its contemporaries to be one of the most modern and productive haciendas in JaliscoKarl Kaerger, Agricultura y colonización en México en 1900, México: Universidad Autónoma de Chapingo, 1982, pp. 204-206.. The forms of hiring labour were a function of the supply and demand of labor and agricultural cycles, and almost in all of them it was a free market for labour, which was not subject to the forced mechanism of peonage by indebtednessSergio Valerio Ulloa. Historia rural jalisciense. Economía agrícola e innovación tecnológica durante el siglo XIX. Guadalajara: Universidad de Guadalajara, 2003, pp. 173-191..

Some of these notes were produced by the firm of Juan Kaiser. Ricardo Delgado, author of Las Monedas Jaliscienses durante la Epoca Revolucionaria, obviously had access to Juan Kaiser’s records and gives detailed listings of the issues for Jalisco. The earliest are ration tokens for the Hacienda de San Juan de los Arcos in November 1913, whilst true ‘currency’ dates from January 1914. These notes are of thick paper or, more often, pressboard and there are a few common designs, most noticeably the round cartón with the denomination on the face and the same in Roman numerals (and often the hacienda’s brand) on the reverse. They usually carried the imprint “J.K.G” (for Juan Kaiser Guadalajara) or some variation, and the number of the order (modelo) which allows the various issues to be dated.

Others were produced by the printer José María Iguíniz or the firm of Anciro y Hermano.

A group of these local issues refer on the reverse to Article 246. Some are so similar that they were obviously produced by the same printer. The article in question is that of the general legalisation on stamp duty (Ley de la Renta Federal del timbre) of 1 June 1906, which makes provision in the event of a lack of revenue stampsArt. 246. Si en algún lugar faltaren estampillas, el que necesite timbrar un documento ó libro lo presentará á la oficina del Timbre para que lo legalice, previo el pago del impuesto de las estampillas que debieran usarse, y poniendo una nota de legalización que autorizará el jefe de la oficina, quien expedirá al interesado una certificación de haber hecho el pago en efectivo por falta de estampillas and states that the holders of documents should present them to the oficina del Timbre and the jefe will certify that the holder has paid cash in place of the required stamps. The following article 247Art. 247. La referida legalización solamente surtirá efectos durante el término de dos meses, pasados los cuales el documento ó libro se tendrá como no timbrado si no se le hubieren adherido las estampillas faltantes. A este fin, los interesados concurrirán á la oficina del Timbre, dentro de dichos dos meses, y canjearán el certificado por las estampillas correspondientes, que se les ministrarán sin causa de nuevo pago, y se adherirán y cancelarán por la misma oficina en el documento ó libro respectivo. Si el documento no estuviere en poder de la persona que hubiere pedido su legalización, recogerá las estampillas en cambio del certificado y cuidará de remitirlas al tenedor del documento para que éste las adhiera y cancele en la forma legal, con la fecha en que sean adheridas states that this certification will only last for two months, after which the holder needs to represent the documents for the necessary stamps to be attached.

The following notes refer to Article 246:

| Issuer | date | certified by | in |

| P. H. Ramsden | April 1915 | J Ignacio Ochoa, Administrador Subalterno del Timbre | Ciudad Guzmán |

| Hacienda El Refugio | May 1915 | S. Mejía, Agente del Timbre | Tonaya |

| Hacienda de Apulco | May 1915 | M. Flores, Agente del Timbre | San Gabriel |

| Inocencio R. Preciado | August 1915 | [ ], Administrador Subalterno del Timbre | Autlán |

while the following mention both Articles 246 and 247:

| Issuer | date | certified by | in |

| Hacienda El Rincón | July 1915 | J Ignacio Ochoa, Administrador Subalterno del Timbre | Ciudad Guzmán |

As local currency these notes’ circulation would have been extremely restricted and it is not surprising that they are extremely rare. Even in Delgado’s time he was unable to locate examples of some of the notes.

Most of these haciendas were at the end of their prosperity, and would be broken up after the Revolution. A Google search shows that many are now luxurious hotels (weddings a specialty) whilst others are ruins, but still magical.