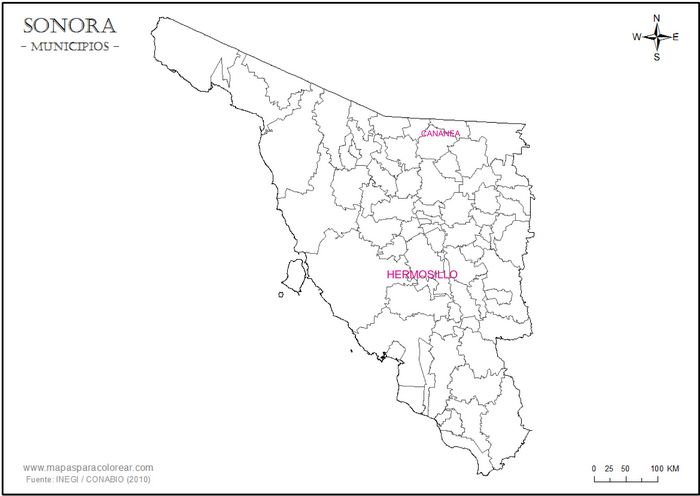

Cananea

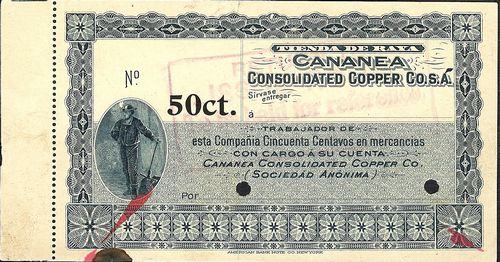

The large American-owned mine at Cananea was the source of examples of both types of private issues - coupons for use in the tienda de raya and emergency currency printed during the revolution.

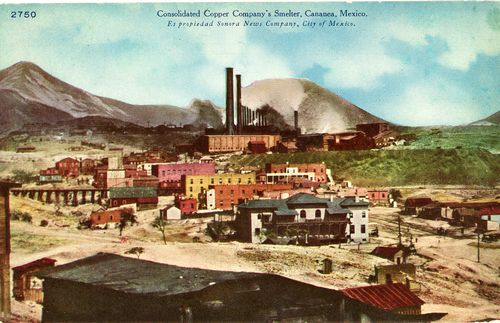

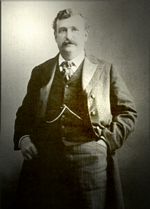

Its developer, William Cornell Greene, was born in Duck Creek, Wisconsin in 1851. In the 1890s he became interested in Sonora and secured from Governor Pesqueira’s widow an option on the Cobre Grande group of mines. He raised the money with a dubious prospectus and in September 1899 organised the Cananea Consolidated Copper Company and its parent, the Greene Consolidated Copper Company. Cananea became the leading mining centre of Mexico. With 25,000 inhabitants, it was one of the biggest cities of Sonora, enjoyed one of the highest percentages of growth in Mexico, and until 1907 benefited from the boom in copper. In 1906, in order to raise additional capital and expand operations, Greene entered into a partnership with Thomas F. Cole, a well-known copper entrepreneur. Together they formed the Cananea Central Copper Company. The same December they formed the Greene Cananea Copper Company which controlled both the Cananea Central Copper Company and the Greene Consolidated Copper Company. In February 1907 Cole and his associate from the Anaconda Corporation, John D. Ryan, wrested control of the Greene Cananea Copper Company from Colonel Greene, who had no subsequent involvement in operating the Cananea mines.

Its developer, William Cornell Greene, was born in Duck Creek, Wisconsin in 1851. In the 1890s he became interested in Sonora and secured from Governor Pesqueira’s widow an option on the Cobre Grande group of mines. He raised the money with a dubious prospectus and in September 1899 organised the Cananea Consolidated Copper Company and its parent, the Greene Consolidated Copper Company. Cananea became the leading mining centre of Mexico. With 25,000 inhabitants, it was one of the biggest cities of Sonora, enjoyed one of the highest percentages of growth in Mexico, and until 1907 benefited from the boom in copper. In 1906, in order to raise additional capital and expand operations, Greene entered into a partnership with Thomas F. Cole, a well-known copper entrepreneur. Together they formed the Cananea Central Copper Company. The same December they formed the Greene Cananea Copper Company which controlled both the Cananea Central Copper Company and the Greene Consolidated Copper Company. In February 1907 Cole and his associate from the Anaconda Corporation, John D. Ryan, wrested control of the Greene Cananea Copper Company from Colonel Greene, who had no subsequent involvement in operating the Cananea mines.

Like the other major American mining companies the Cananea Consolidated Copper Company operated a tienda de raya but settled on paydays with paycheques or cash. For many workers the final payout was low: the cheques on display in the Museum at Cananea show an average monthly wage of twenty-eight pesos but with average deductions for rent, hospital insurance, goods purchased on credit, fiestas, etc. of $27·75 leaving just 25 centavos to be paid out.

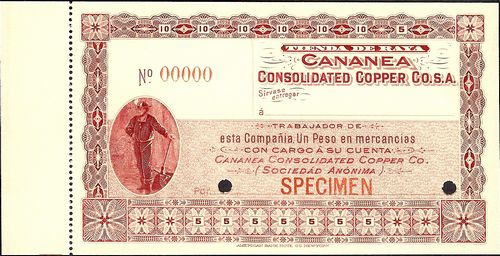

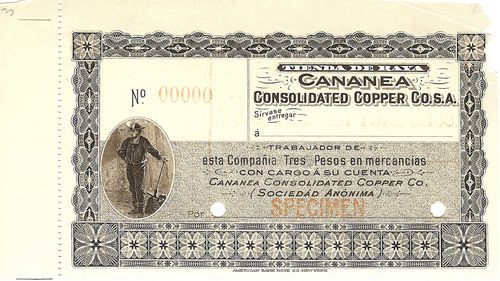

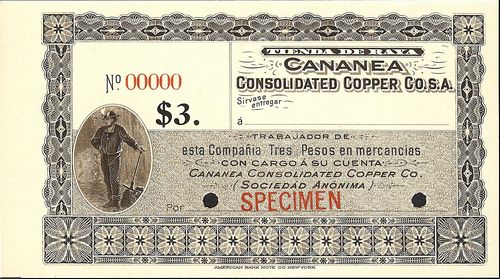

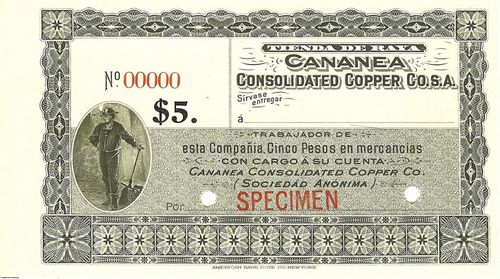

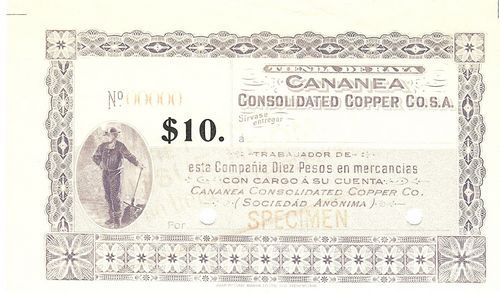

The company’s tienda had a working capital of 180,000 pesos and annual sales of 145,000 pesos. The tienda operated a check-off scheme by which the company gave workers scrip (boletos)[image needed] to be exchanged in the tienda for merchandise. In 1902 the boletos had the legend Tienda de Raya / Consolidated Consolidated Copper Co., S.A. / Sirvase entregar a _______________________ / Trabajador de esta Compania / _______ pesos en mercancias con cargo a su Cuenta. / Cananea Consolidated Copper Co., S. A. and were probably printed by the Ketterlinus Lithographic Manufacturing Company of PhiladelphiaCCCC papers, letter from George Robbins, New York to John A. Campbell, Cananea, 9 June 1903.

The company argued that it did not use the boletos as currency. “… with us they constitute merely a certificate that a certain workman has performed certain labour and has a balance due him of a certain amount. Each ticket as issued is properly stamped and none are reissued after having been taken in by the Mercantile Department. Another reason why it is necessary that we use something of this character is the absence of small coin for change. There being no mint in this State, it would be a very difficult matter for us to provide adequate coin for change were the use of boletos here abolished"CCCC papers, folder 1, letter from A. W. Burchard to A. C. Bernard, Hermosillo, 28 April 1902.

In April 1902 a complaint was made to the Federal government that the company was paying its workers other than in efectivo, in contravention to the law, and an investigation ordered through the District Judge at Nogales. The company consulted its lawyer, licenciado Pesqueira, who had had considerable experience in defending other mining companies in similar circumstances. Pesqueira reported that the usual policy of the government was to allow matters to run along until a complaint was made, then to order an investigation and impose a fine, after which the company would continue as usual until further agitation. He did suggest, however, that the company change the legend from ‘en mercancias con cargo á su cuenta’ to ‘en mercancias con cargo a nuestra cuenta’ , as this complied as near as possible with the law. The judge referred the matter to Mexico City so the company asked its lawyer in Mexico City, Tomás Macmanus, to lobby the federal authoritiesCCCC papers, folder 1, letter from A. W. Burchard to Tomás Macmanus, Mexico City, 5 May 1902.

M754b CCCC 50c without denomination

M754a CCCC 50c with denomination

M754a CCCC 50c with denomination

M755b CCCC $1 without denomination

M755a CCCC $1 with denomination

M755a CCCC $1 with denomination

M756a CCCC $3 without denomination

M756b CCCC $3 with denomination

M756b CCCC $3 with denomination

M757a CCCC $5 with denomination

M757a CCCC $5 with denomination

M758a CCCC $10 with denomination

M758a CCCC $10 with denomination

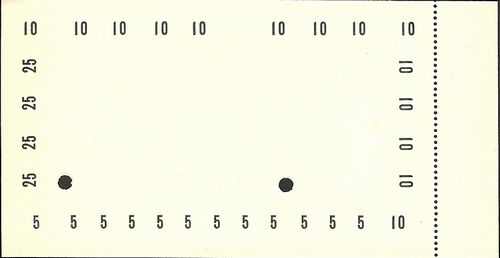

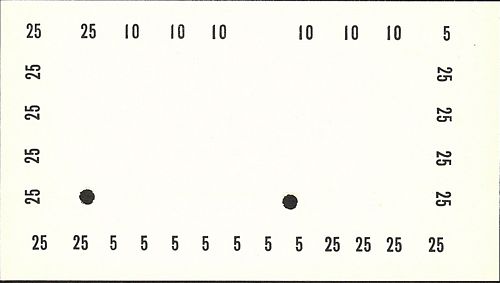

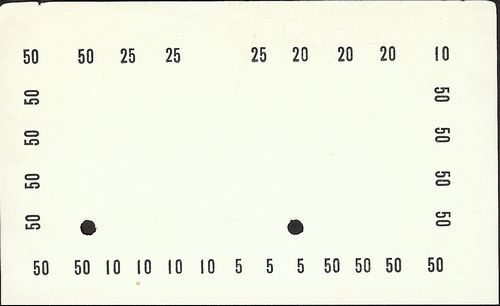

At this very time the company was negotiating with the American Bank Note Company for a new series of boletos. Proofs (50c blue, $1 red, $3 brown, $5 green on white card and green on cream card and $10 purple) dated June 1902 and January 1903 are known. These notes had a sequence of values on the face or reverse so that the purchases could be checked off until the card was completely used. Burchard wrote to ask whether the company could make the proposed change without damaging the plates: otherwise it would use the existing platesCCCC papers, folder 1, letter from A. W. Burchard to Philip Berolzheimer, New York, 19 May 1902. So the issued notes could have had either the earlier or the revised text.

In 1903 the greater portion of paymaster’s cheques delivered to employees at the outlying camps were cashed by brokers. This resulted in a considerable loss to the employees, in the exorbitant rates of exchange charged, and to the company, in the loss of exchange and deposits for the company’s bank. The outside brokers did a considerable business in advancing money on identity cards (carteras) as there was a long wait between pay-days and, as the company manager George Young acknowledged, it would have been too much to expect the general run of employees to wait for their pay in regular course. The company did occasionally advance money to employees between paydays but did not encourage them to ask for such advances. As the brokers at the outside camps charged interest at 5% to 10% per month, Young suggested that it would be possible to protect the men and profit the company by advancing to a broker sufficient money to carry on the business, advances to be made on a regular schedule of ratesCCCC papers, letter from George Young to James H. Kirk, 17 March 1903.

By November 1905 the company could claim that the employees were paid in cash and could buy goods where they likedEl Paso Herald, 15 November 1905 but at the time of the 1906 strikeThe strike at Cananea was one of the events that set the stage for the rebellion of 1910. The strike was caused by declining export markets, fear of unemployment, and fear and envy of foreigners. Cananea employed 5,360 Mexicans and 2,200 foreigners, mostly Americans. No one disputed that Greene paid the highest wages in Mexico (to quote Governor Izábel, the miners dressed in the clothes of the middle class, equipped their homes with modern appliances, and purchased the latest furniture) but judged by the income of miners in Arizona and by the income of the Americans at their own mines, Mexicans fared poorly. Nor did Mexicans enjoy job security, which occurred only with high copper prices: the collapse of the copper market in 1907 meant that miners lived with the fear of unemployment. On 31 May 1906 the night shift at the Oversight went on strike. The next day workers at Capote and Veta Grande mines, the smelter and the concentrator followed suit. A delegation presented demands that focused directly on conditions in the mines: the dismissal of a foreman at the Oversight mine; a reduction of working hours from nine to eight; a basic wage of five pesos; promotion for Mexicans according to their abilities; and a new rule that, where abilities were equal, the workers in any given division should be 75 percent Mexican and 25 percent non-Mexican. These demands were incorporated into a manifesto which attacked Díaz’ dictatorship as an ally of foreign employers. The same evening, three thousand strikers marched through the streets of Cananea, waving Mexican and a few red flags and holding placards which proclaimed ‘Five pesos for eight hours!’ The demonstrators successfully called on those still at work to join the strike, so that a total of 5,300 miners were involved in the movement. Accounts over what followed differ, but there was some fighting between company guards and the strikers in which the lumberyard manager, George Metcalf, his brother Will and three strikers were killed. The battle raged for two days between, on the one hand, workers poorly armed with rifles and pistols which they had seized, almost without ammunition, in an assault on the company store, and on the other hand, well-armed federal troops backed by a 275-strong battalion of United States ‘rangers’ who crossed the border from neighbouring Arizona at the invitation of governor Izábel (though they took no part in the dispute). Before the strike subsided, half a dozen Americans and thirty Mexican miners had died. This invasion of Mexican soil by armed Americans raised a public outcry. Madero publicly condemned the use of American mercenaries to squash the strike at Cananea. Díaz, he said, should have compelled the owners to pay higher wages. After the strikers were defeated, their leaders received long prison sentences and were only freed by the revolution. the Flores Magóns' newspaper Regeneración claimed that whereas Americans were paid in cash, Mexicans were paid in boletos for the company’s tiendas de raya, where shoddier goods were sold at prices two or three times higher than normal. When a Mexican worker needed to change his boleto into cash, the company redeemed them for 75% of their valueRegeneración, 15 June 1906. These claims were in fact compatible. Cananea lies 62 kilometres south of the United States border and most of its consumer goods, including staple foods, were imported. In 1905 the Mexican devaluation of the peso by 50% devastated the real wages of the miners. They faced the immediate loss of half of their buying power because the company insisted on paying them in Mexican and non-gold based scrip instead of gold or US dollars. American employees were paid in US currency (and enjoyed higher wages to begin with)..

As a result of the financial crisis of 1907 the Cananea Consolidated Copper Company began laying off workers in September, ceasing all operations by the year's end"No se deben alarmar," Heraldo de Cananea, 30 September 1907. In the words of one observer, "long wagon-trains, burros-trains, and people on foot are pouring down the 60 miles of highway from Cananea to Imuris . . . penniless . . . not knowing how they are going to feed themselves on their long journeys to distant homes”Mining and Scientific Press, 16 November 1907. As news of the mine closures reached Nogales, Manuel Mascareñas reported that officials had been forced to close the Bank of Sonora as panicked depositors demanded their moneyAER, Copiadora, Julio 1906/Enero 1911, 15 September 1907, Manuel Mascareñas to Max Müller. The mine remained closed until the summer of the following year.

By 1908 the company had been fined two or three times and finally ordered to discontinue the use of boletos. The matter was laid before the Secretaría de Hacienda in Mexico City, and the Secretario or Sub-secretario drafted a new form of wording. The company was told that they could use this as a libreta or little book, in other words as a substitute for a pass book. In September 1908 the Greene Gold-Silver Company in nearby Temosachic, Chihuahua, was fined for using an identical libreta and the general manager, George Young, suggesting again using Tomás Macmanus to lobby the Secretaría de HaciendaCCCC papers, folder 5, letter from Young to L. D. Ricketts, 8 September 1908.

In 1910 Young wrote that the company had one regular pay-day or final settlement day each month, but all of the employees were at liberty to draw food supplies, merchandise, meat etc. daily on their accounts and could draw cash once in each week in addition to their final settlement. The pay department was open every day for this service except Sunday, but the same man was not permitted to draw cash more often than once in each weekCCCC papers, letter from Young to R. G. Dun and Co., Guaymas, 29 June 1910. By 1913 the Prefecto of Cananea could report that the company had paid in banknotes and silver coins for several yearsAGHES, Fondo Oficialidad Mayor, tomo 2971, telegram, 23 September 1913, but he was hardly an impartial commentator.

As stated, as a result of the collapse of the market for copper in 1907, the mines at Cananea were shut down. Although some were partly reopened the next year, Greene himself admitted that the jobless filled the streets of Cananea. By 1911, Cananea had lost two-fifths of its inhabitants, and not until that year did its mines pay dividends to their shareholders. On 9 May 1911, Cananea fell to Juan Cabral and his men, the first city in Sonora to be captured by rebels. Greene himself was killed in a buggy accident in 1911 whilst relocating to the United States in the face of revolutionary activity.

The Cananea company suspended operations from August 1914 to June 1915 and again from June to December 1917, because of the depressed copper market and the constraints imposed by the Constitutionalist government. In 1917 the assets of the Greene Consolidated Copper Company were sold to the Greene Cananea Copper Company and the former dissolved the following year. The Cananea Consolidated Copper Company continued to operate as a Mexican subsidiary of the Greene Cananea Copper Company.

Cananea is one place suggested as the origin of the word 'bilimbique'. It is said that local businesses would accept the company’s chits (vales) if they had been signed by the cashier, an American called William Weeks, which the Mexicans pronounced ‘Biliam Biqs’ and the notes soon became ‘bilimbiques’The Numismatist, October 1915. Other explanations mention a William Wicke of the mine La Veladeña in Durango; William Vicks, an American miner in Sonora with his own tienda de raya (Tim Turner of Associated Press, quoted in I. Thord-Gray, Gringo Rebel (Mexico 1913-1914), Miami. 1960), or ‘Billis Ticket’, a name given the vouchers of the Cananea mining company. Later the name was applied to any vale or note of dubious value and during the revolution it was applied to the Constitutionalist currency.