El Banco Nacional de Tejas

José Félix Trespalacios was a veteran revolutionary leader of the Mexican movement for independence. For ten years he served the cause throughout Mexico and was forced to flee to Havana and thereafter to New Orleans. Shortly after Iturbide proclaimed his Plan de Iguala and entered Mexico City in victory, Trespalacios returned to Mexico, took his oath of allegiance to Emperor Iturbide, and was appointed colonel of the army and political chief of the Province of Texas, where he took the first steps for the establishment of a bank.

The occasion for this innovation was the irregularity with which hard money was sent from the treasury in San Luis Potosí for the payment of troops and other public officials in San Antonio. Troops were traditionally paid in specie (gold or silver coinage) sent under guard from the nearest treasury. While Spanish authorities had never failed to eventually send money, relatively long and irregular periods elapsed between paydays and the local merchants had to extend credit in the interim.

Trespalacios concluded that the establishment of a national bank, whose notes were guaranteed by specie, would solve the problem. Through the bank he would be able to pay the troops with regularity, the merchants would in turn be paid with notes secured by specie, and when the specie shipments arrived, they would constitute the bank reserves with which the notes could be redeemed.

Trespalacios presented his plan to the City Council for approval and it was unanimously approved. The Council recommended that the notes be declared legal tender for all transactions and be made acceptable for payment of taxes and the purchase of public lands. It was then voted that three members of the city council be made officers of the bank in order to add the prestige of the local merchants and officials to the paper money issued by the bank. The three officials were to be required to countersign all notes. The paper money was to be guaranteed by the specie expected from the government, and was not to exceed this amount.

After the attainment of independence in 1821, Texas, Nuevo León, and Tamaulipas were placed under a new commandant-general with headquarters in Saltillo. It was to this district superior, Colonel Gaspar López, that Trespalacios presented his plan for a bank. López sent the plans on to Mexico City for formal approval by the Iturbide government.

Without waiting for formal authorization, Trespalacios issued a decree[text needed] on 21 October 1822, stating “I hereby order and command that a National Bank be established temporarily in this Province, subject to its ultimate approval by the Government.”

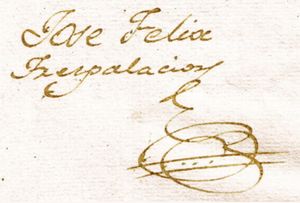

Trespalacios ordered paper money to be issued in the amount of fifteen thousand pesos, which would be sufficient to pay the troops and pay for supplies for a three month period. The currency would be signed by Alcalde José Salinas, Councilmen Vicente Travieso and Miguel Arciniega and Trespalacios himself.

| José Maria de Jesús Salinas was born on 17 November 1797, the youngest child of Manuel Salinas and María Ignacia Flores. During his early years the family lived on the Rancho de San Bartolomé, one of eleven family ranches, and in San Antonio, where Manuel Salinas served in city government until 1817. After Mexican independence, Salinas served as alcalde of San Antonio, in 1822, 1827, 1830, and 1836. He was the last San Antonio alcalde before Texas independence. He and his brother Pablo, who served with Col. Juan N. Seguín, were fervent supporters of Texas independence. As an owner of multiple ranches, the Salinas family supplied and offered shelter to the volunteer army of Texas. Texas forces under Travis and Fannin camped on his ranch. He died in June or July 1851. His sister, Antonia Salinas de Barrera, and her husband were made administrators of the estate, which remained in probate until 1868. | |

| Vicente Travieso | |

|

Arciniega was assigned as a secret agent by Spain to gather information on the whereabouts and the movements of both enemies of Spain, France and the United States, making it essential for him to be fluent in Spanish, English and French. he also had fluency in several different dialects of native Indians. In 1826, when he was sent to learn the intentions of the Cherokee Indians, he met the chief Richard Fields and leaders of the Comanche, Tahuallace, Tejas, and Caddo Indians at Laguna de Gallinas, near Nacogdoches. Arciniega fought in the War of Independence with his father Gregorio Arciniega and uncle Felipe Arciniega. Arciniega was arrested in October 1826 by alcalde Juan José Zambrano for signing a document for María Josefa Seguín but was evidently exonerated, as in December he was appointed captain of the civil militia. By April of 1827 he and Ángel Navarro were elected commissioners, and the following month he and José Antonio Navarro were elected deputies to the state congress at Saltillo, where they managed to pass a law allowing slavery in Texas. In November 1830 José Miguel was appointed Land Commissioner for Stephen F. Austin’s colonies by the Mexican Supreme Government. Arciniega served as the public treasurer, political chief, judge, captain of the militia, general inspector of arms, and alcalde of San Antonio in 1830 and 1833. He assisted Austin to convince the Tejano leaders in San Antonio to side with Austin in the convention of 1833 to separate Texas from Coahuila. From 1832 to 1835 José Miguel was approved by the Mexican Supreme Government to purchased 11 leagues of land, that is equivalent to 48,703 acres, in the neutral land or buffer zone between Northern Texas and Louisiana’s U.S. border. On 11 December 1835 he was appointed interpreter by General Martín Perfecto de Cos in negotiations with General Edward Burleson for the surrender of Bexar. It is unclear whether he supported the Texas Revolution, as he was appointed Bexar delegate to the Convention of 1836 but did not attend. He was very active during the Republic of Texas era and served as a probate and an associate judge, Bexar County Commissioner, Alderman, secured the borders at the Rio Grande under the instructions of President David G. Burnet, and was a well-known lifelong merchant of sugarcane, potatoes and corn. He died on 13 May 1849. |

|

|

José Félix Trespalacios was a member of the Chihuahua militia from 1810 to 1814, when he was tried for conspiracy to provoke a rebellion and was sentenced to death, but the sentence was commuted to ten years. In San Luis Potosí on the way to Mexico City, he escaped and joined rebels under Sebastian Gonzáles. In a battle with royalist forces Trespalacios was captured and put in the fortress at San Juan de Ulloa with the officers of the Francisco Xavier Mina expedition. Again Trespalacios escaped. He went to New Orleans, where with the aid of local merchants he organized an expedition to aid the Mexican independence movement and joined forces with James Long, becoming nominal commander of the Long expedition. He followed Long to Texas in November 1820 and subsequently went to Mexico with Benjamin Rush Milam to attempt to combine efforts with Agustín de Iturbide. Trespalacios landed at Campeche, declared for the Plan of Iguala, was imprisoned and later released by the Iturbide government, and late in 1821 helped secure the release of Long and members of his party. Trespalacios was named colonel of cavalry by the regency and was appointed governor of Texas by Iturbide, serving from 17 August 1822 until his resignation on 17 April 1823. Trespalacios was senator from Chihuahua to the Mexican National Congress from 10 January 1831 to 1 December 1833, and served as commandant general and inspector of Chihuahua from 10 January 1833, until his retirement from the army on 15 December 1834. He died at Allende, Chihuahua, on 4 August 1835. |

|

The new institution was officially designated the Banco Nacional de Tejas. Four soldiers were ordered to make by hand the notes in the various denominations. Records indicate that the soldiers initially prepared ten $100 notes, ten $50 notes, fifty $20 notes, 100 $5 notes, 600 $1 notes, 600 four reales notes, 200 two reales notes and 100 one real notes for a total of approximately $4,462 pesos to be issued on 1 November 1822.

Trespalacios sent the first group of new bank notes to the commander of the garrison at La Bahia (Goliad), and instructed him to read the decree in the town square. Captain Francisco Garcia replied on 9 November 1822, that he had complied with the governor’s instructions and that the paper money had been well received and generally accepted. Since more than half of the currency sent was in large denominations, Garcia suggested that the next remittance should consist of notes of only ten pesos or less. “In this Presidio,” he explained, “there are no persons capable of exchanging for cash notes of higher denominations.”

The Banco Nacional de Tejas was created shortly before a somewhat similar institution was authorized in Mexico City by Imperial decree of Agustín de Iturbide. While there are no records directly linking the two, it is a distinct possibility that Emperor Iturbide’s decision to issue paper money was in part caused by Trespalacios and the Banco Nacional de Tejas, especially when the struggling government of independent Mexico was faced with serious financial problems. Although Iturbide did not order the establishment of a bank, he did authorize the national treasury to issue paper money in the amount of the revenue expected within the following ninety days.

Iturbide’s decree was published on 29 December 1822. The instrument bears a remarkable resemblance to the decree issued by Trespalacios in Tejas. It declared that the government found itself obliged to resort to paper money in order to meet the obligations of the government. It stated, as did the Texas decree, that the measure had been approved unanimously by the national council. The national treasury was authorized to issue paper money in the amount of 84,000,000 pesos, redeemable within one year, with the resources of the nation pledged as security. The treasury was empowered to print 2,000,000 one peso notes, 500,000 two peso notes, and 100,000 ten peso notes. The new currency was declared legal tender.

After 1 January all payments made by or to the national treasury were to consist of one third paper money and two thirds silver. This provision made it necessary for citizens to secure treasury notes to the extent of one third their obligations for taxes and other indebtedness to the national government. All business transactions that involved more than three pesos had to be satisfied in both currency and silver. Violations of the new law were subject to heavy fines and imprisonment. The notes taken in as payment for government taxes and other obligations were to be destroyed to prevent further circulation.

In the meantime the notes of the Banco Nacional de Tejas were being circulated without difficulty. The four men assigned to make them by hand had turned out a new issue for December which consisted of approximately $7,375 pesos.

Governor Trespalacios received a request for payment for drafting work from the four men preparing the notes on 2 December 1822. Trespalacios turned the matter over to the city council for its members to determine what would be a fair compensation. Penmanship and artistic design were evidently not held in very high esteem in those days since the council decided to pay the sum of fifty pesos for all four scribes. The soldier in charge put it on the record that he was accepting the money under protest, declaring the sum was totally inadequate for the exacting labor required of the four men.

Commandant General López wrote to Trespalacios from Saltillo on 18 January 1823, regarding the new paper money being printed by the national treasury. He informed Trespalacios that the emperor had requested all officials to explain to the public the advantages of paper money. In the future, López continued, all troops and public officials were to be paid one third in national treasury notes and two thirds in cash.

Although nothing was said in regard to the Banco Nacional de Tejas, the governor and his friends immediately became apprehensive. If full specie payment for the troops could no longer be expected, the notes of the Texas bank could not be redeemed at their face value with specie. Since the Texas notes had been issued on the expectation of full specie payment, public confidence was seriously shaken. The governor reluctantly had to publish the national decree regarding the treasury notes, thus advising the citizens that the Texas notes had a rival currency and were no longer backed by 100 per cent specie.

At the same time the Secretary of the Treasury of Mexico issued a circular[text needed] declaring that Emperor Iturbide had decided that the paper money created in Texas by Governor Trespalacios should be replaced by the new federal currency. The secretary added that a sufficient amount of paper money was on its way to the Intendant of San Luis Potosí, who had been instructed to call in all the notes issued by the Banco Nacional de Tejas and exchange them for the new treasury notes. The intendant of San Luis Potosí had been ordered to burn all the Texas notes upon their presentation for exchange.

Governor Trespalacios was instructed to gather all the notes of the defunct Banco Nacional de Tejas and send them to San Luis Potosí to be exchanged. Fortunately for him, he was spared this painful duty by being sent to another province. After his departure the note holders refused to surrender them in the hope that the original agreement would be eventually fulfilled by the government. They maintained that the notes of the Banco Nacional de Tejas were redeemable in silver or gold only.

For two years the note holders refused to surrender their notes and repeatedly pointed out to the government that they had given their cash and their goods in exchange for the Banco Nacional de Tejas currency under a solemn agreement that it would be redeemed in specie. They refused all offers to exchange their Texas notes for national paper money. Early in 1825 the city council of San Antonio presented a petition in the name of the people of Texas to the governor of Coahuila and Texas — the two provinces had been joined — requesting settlement. Reluctantly they admitted their willingness to exchange the Texas bank notes for full or partial payment in specie.

In May 1825 some citizens of San Antonio tried to use their notes by contributing to a fund for establishing a tobacco factory in Saltillo. However, their contributions were refused because they had been made “en papel del Banco Nacional de Tejas”statement dated Sala Capitular de Bejar, 8 May 1825, and signed by Juan Martín de Beramendi, at this time first alcalde of Bexar in Lista Que Manifiesta el prestamo y Donativo voluntario que en reales y efectos han hecho los Pueblos del Estado para el establecimiento de la Fabrica de Tabacos de esta Capital en virtud de la circular expedida por este Gobierno con fecha 20 de Marzo de este año, y se publíca por disposicion del Honorable Congreso de 30 de Junio del mismo. Imprenta del Gobierno á cargo del C. José Maria Praxedis Sandobal, Saltillo, [1825].

The matter was presented to the President but other questions more pressing occupied his attention. Not until four years later was the matter finally settled. President Vicente Guerrero issued a decree on 8 May 1829, ordering the national treasury to pay the citizens of San Antonio for the paper money issued by the Banco Nacional de Tejas. On 10 June Juan Fuentes, the alcalde primero of Saltillothen called Leona Vicario. Saltillo’s name was changed to Leona Vicario on 5 November 1827 but the town was renamed Saltillo on 2 April 1831 reported that he would publish the decreeACoah, Fondo Siglo XIX, 1829, caja 6, folleto 7, exp. 8 letter Juan Fuentes to governor, 10 June 1829.

On 22 February 1830 the state government reportedACoah, Fondo Siglo XIX, 1830, caja 2, folleto 7, exp.10 that it had amortized 2,556 notes of ten different denominations, totalling $8.412.25, and comprised as follows:

| Denom. | Number | Value |

| 1 real | 6 | $ .75 |

| 2 reales | 446 | 111.50 |

| 4 reales | 648 | 324.00 |

| $1 | 999 | 999.00 |

| $2 | 1 | 2.00 |

| $5 | 215 | 1,075.00 |

| $10 | 91 | 910.00 |

| $20 | 112 | 2,240.00 |

| $50 | 21 | 1,050.00 |

| $100 | 17 | 1,700.00 |

| $ 8,412.25 |

(Based on "Banco Nacional de Texas and Iturbide Currency" by Cory Frampton, USMexNA journal October 2010)

José Miguel de Arciniega

José Miguel de Arciniega