The revenue stamps on Mexican banknotes issued by the private banks

by Cedrian López-Bosch Martineau

Banknote collectors of private issuing banks in Mexico tend to focus mainly on the vignettes, dates and even signatures, but less interest is aroused around a feature present in most of their notes, the revenue stamps generally printed on the back. Usually there were two stamps; one with the name of the issuing bank and a revenue stamp certifying the payment of the Revenue Stamp Tax (Impuesto del Timbre or Renta del Timbre). I will leave the former for a later analysis; in this article I intend to review the latter, explain its origin and show the differences and evolution throughout the issues from the 1870s to 1914, when the last banknotes were issued by the private issuing banks.

To organize this article, I will make a brief synopsis of the history of the issuing banks, highlighting some passages and characteristics in order, in the second part, to be able to explain how their banknotes intertwine with the emergence and the evolution of the Revenue Stamp Tax.

Issuing banks and their banknotes

The Banco de Londres, México y Sudamérica was the first in Mexico and was established in 1864 under the Commercial Code. For a decade, it was the only institution issuing banknotes until the 1870s, when a wave of newly created banking institutions emerged in the state of Chihuahua. All of these banks were governed by concession contracts and their terms depended largely on the bargaining power of their shareholders. In most cases it implied the exemption of direct and indirect taxes of one to five years and a great degree of autonomy. When the local government sought to have them at least register their issues at the State Revenue Administration, those exemptions were extended between three and ten years.

At the federal level, at the beginning of the 1880s, new issuing banks were also founded, such as the Nacional Mexicano, the Mercantil Mexicano, and, although it did not issue banknotes into circulation, the Banco de Empleados. These banks were subject to federal supervision; government inspectors could oversee their financial statements and had to certify compliance of a set of requirements before issuing the banknotes. Among these, according to the concession contract of the Banco Nacional Mexicano (Art. 4 §B), there were, in addition to the signature of an inspector of the federal government, “a stamp of the bank and a stamp or seal affixed by the respective Revenue Stamp office…”. While the Bank was exempt from both ordinary and extraordinary contributions, it was obliged to pay for patent rights, the property tax and the stamp revenue, the latter in accordance with the provisions of art. 4 cited above “...of half a cent on the banknotes of one peso to fifty pesos and of one cent on banknotes from one hundred to one thousand pesos.” This, as explained below, constituted an exception to the Revenue Stamp Act.

In 1884, a new Commercial Code was published requiring all issuing banks to renew their concessions in order to request authorization from the Ministry of Finance and level the playing field, submitting them to similar conditions, both for their constitution and for the issue of their banknotes. Specifically art. 967 established the following obligation:

Before issuing its banknotes, the bank shall send them to the Ministry of Finance, which will send them to have a seal or a stamp that each bank determines be affixed, provided that the following requirements are met:

I. That its amount does not exceed the authorized amount.

II. That the banknotes clearly express the place of payment, and the bank’s obligation to reimburse them at sight, to the bearer, in cash.

Once the banknotes have been stamped by the Ministry of Finance, they will be sent to the Revenue Stamp office for the payment of this tax, subject to the regulation accordingly.

The banknotes that lack the seal of the Ministry of Finance, will not produce action, nor will they be enforceable before the courts; and the bank that puts them into circulation will pay a fine of ten percent on the nominal amount of such banknotesCode of Commerce (relevant sections), Mexico City, 15 April 1884/footnote}.

The first bank to obtain a concession based on the new Code was the Banco Nacional de Mexico, as a result of the merger of the Mercantil and the Nacional Mexicano. After these institutions helped the government out of the crisis, they obtained favorable conditions for the new institution compared to the rest of the banks. Among these benefits, it maintained the preferential rates of the Revenue Stamp Tax from the contract of the Nacional Mexicano. While this new bank sought to maintain the recently recognized privileges and create a monopoly, the Banco de Londres, México y Sudamérica decided not to change its concession, challenging the retroactive application of the illegal law and defending the plurality of banks. Without going into details of the controversy, it was resolved when the latter acquired the concession of the Banco de Empleados and would eventually renegotiate its concession, allowing it to continue in office now under the name of Banco de Londres y México, without the reference to South America.

At the end of that decade the Chihuahuan banks also modified their concession contracts, thus standardizing the requirements for establishing banking institutions and issuing banknotes, subjecting themselves to the supervision of the Ministry of Finance and forcing themselves to replace the banknotes in circulation with new under the new conditions, which was partially fulfilled given the complex unification process created by the government. These new contracts also exempted banks from paying direct contributions (on their assets and income) and indirect contributions (for the consumption of goods and services), with the exception of the Revenue Stamp Tax, to be paid “in accordance with the laws in force at present or to reforms that reduce that contribution.“new contracts of concession for the Banco Minero and Banco Mexicano, 22 May 1888, Banco de Chihuahua, 15 December 1888 and Banco Comercial de Chihuahua, 15 March 1889.

According to the new Commercial Code, published in 1889, until a special Act for credit institutions was issued, they ought to have authorization from the Ministry of Finance and be approved by Congress. The system maintained two schemes, on the one hand two national-scale banks, and on the other a multiplicity of state banking institutions. Thus, in addition to the banks of Chihuahua, others appeared in Durango, Nuevo León, San Luis Potosí, Yucatán and Zacatecas. Formally, these contracts extended the intervention of the banks by the Ministry of Finance and all of them were subject to the payment of the Revenue Stamp Tax. Some concessions replicated the requirements for institutions and their banknotes, including the authorization from the federal government, the signature of a government inspector and the presence of the bank’s seal and the Revenue Stamp from the Revenue Stamp Administration proving the payment of such tax, and others simply indicated that they were not exempt from the Revenue Stamp Tax, payable according to laws in force.

Finally, in 1897 the General Act of Credit Institutions regulated banks and their activities; defined and distinguished those of issue, the refactional and mortgage banks. The only ones entitled to issue banknotes were the issuing banks and among their requirements was the obligation to pay the Revenue Stamp Tax and use this means as a way to ensure compliance with the necessary requirements:

No banknote will be put into circulation without the corresponding revenue stamp, which will be engraved on the same banknote by the Revenue Printing Office. The order will only be issued by the Ministry of Finance, after checking that the quantity of banknotes fits within the limits set for issuance in the first part of article 16General Law of Credit Institutions, Mexico City, 19 March 1889.

Thus, new issuing banks emerged, practically one in each state but there were also others that took advantage of the new regulation to become refactional banks such as those of Michoacán and Campeche or to consolidate as those of Chiapas and Oaxaca that merged with the Oriental. Thus, at the end of the Porfiriato we had 24 banks of issue.

The government inspectors certified compliance with all the necessary requirements to issue the banknotes into circulation and signed them. Once this was done, the banks sent them to the Ministry of Finance to engrave the two stamps on them, usually on the back. The first was a guilloche for each issuing bank, as a countersign, whose color and position varied according to the year of issue and the denominationPrior to regularizing concessions in 1889, the guilloche only had the name of the bank. Afterwards, it had both, the name of the bank and the one of the Ministry of Finance.. The second was the Revenue Stamp, which certified the payment of this tax. This one also changed every year as will be seen below. The banknotes were then sent back to the issuing banks’ vaults to await putting into circulation.

The Revenue Stamp Tax

In parallel to the banking institutions, a new institution also emerged in Mexico in the last third of the 19th century, the (fiscal or revenue) Stamp: “a mark or seal whose shape and design are determined by law, and which is printed by the officials of this special service, on the paper intended for certain uses. As this is subject to the prior payment of a tax by the consumer, by extension [it will be given] the name of Stamp, to the tax that constitutes the collection of this tax... it enters by its nomenclature in the category of indirect contributions.”Memorias de la Secretaría de Hacienda y Crédito Público 1874-75, pp 122

After more than a decade of planning it, the decree creating the Revenue Stamp Tax was finally issued on 31 December 1871 to replace the stamped paper inherited from the Colonial era. Its objective was to reorganize, modernize, facilitate and consolidate the public finances: at first it only replaced the stamped paper, but soon it was extended to consumption taxation on previously non-taxed economic activities. Two types of stamps were created: those of Documents and Books and those of the Federal Contribution - to which later those of Internal Revenue, Maritime and Border Customs and some special ones for specific products were created - valid for a fiscal year, from July of one year to June of the following, as indicated by the stamp itself. Banknotes were expressly mentioned within the Documents and Books stamps and their rate, unlike other procedures whose fee was fixed or paid per sheet, was defined according to their value, among a hundred other commercial activities subject to this tax that had to leave a record of the transaction (art. 4):

17. From ten pesos onwards, the revenue stamp that each banknote will pay will be equal to that indicated for receipts (see below). i..e. any document issued to safeguard or justify any payment or money order made, including vouchers to the bearer or to a specific person or company, checks, banknotes, insurance policies, deposit documents… (art. 4, para 102)

Each bank note will [only] legally circulate when it contains, canceled by the grantor, the stamp or stamps corresponding to the fiscal yeaar in which it circulates. The lack of a stamp or its cancellation will be punished in accordance with article 26.SHCP, Revenue Stamp Law, 31 December 1871. In Carlos Sierra and Rogelio Martínez, El papel sellado y la Ley del Timbre, 1821-1871-1971, SHCP, Mexico City, 1972, p 173

As the fee to be paid by banknotes was associated with the rate of receipts, it is relevant to know this latter:

| An amount in money or in values of ten pesos without reaching one hundred | $0.05 |

| one hundred pesos without reaching five hundred | $0.10 |

| five hundred pesos without reaching a thousand | $0.15 |

| one thousand pesos without reaching two thousand five hundred, for every hundred pesos or additional fraction five cents of one thousand pesos without reaching two thousand five hundred, for every hundred pesos or additional fraction | $0.05 |

It is worth highlighting two elements of this first Revenue Stamp Act: the banknotes would only be legally issued when they met this requirement and denominations of ten pesos and less would be exempt. Unlike other documents to which the stamp would be adhered, for which adhesive stamps would be manufactured, the stamps on the banknotes, identical to those, would be printed directly.

To implement this law it was necessary to establish a specific engraving and printing office in our country. Thus, the Stamp Printing Office, also known as the Stamp or Revenue Printing Office was also formally created in 1871 within the Ministry of Finance: however it began to function a few years later, after a commission was sent abroad to learn the state of the art of steel engraving and to acquire machinery and supplies in 1873.Memorias de la Secretaría de Hacienda y Crédito Público, 1872-1873, pp. 64-65 The printing presses were initially located in the Old Archbishop’s Palace, next to the National Palace in Mexico City’s downtown. From there they moved to the San Cosme gatehouse and later returned to the National Palace. It is important to take into consideration that this office was only in charge of printing the stamps, but previously the tax needed to be collected and the fees to undertake this task paid to the Revenue Stamp office, as well as the written instruction from the Ministry of Finance needed to be issued.

The new intaglio technology made it possible to print the stamps in relief, difficult to reproduce, thus becoming an authentication factor and a security measure. They were engraved on the back of the banknotes trying to find an empty space that would allow them to be visible and distinguish them from the engravings on the note. The Revenue Stamp regularly was on the left side, either in the corner or on one of the edges, while the bank’s guilloche was normally on the right, although there were exceptions; some were printed over the engravings, with little contrast or coinciding with the folds, making it difficult to distinguish clearly, especially in well circulated and worn banknotes.

At that time, the only issuing bank was still the Banco de Londres, México y Sudamérica. It is to be assumed that its first notes, put into circulation in 1865 and 1866, of an unknown printer, were not stamped since they preceded this law. This is also the case of those produced by the English company Thomas de la Rue, of which only pieces issued dated 1872 are known, which despite being issued on a later date, due to their value, namely five and ten pesos, were not obliged to pay the tax. However, it is not clear if any of the $20 to $1,000 banknotes printed by the American Bank Note Company (“ABNC”) between 1866 and 1870 bear a revenue stamp under this lawAn intriguing reproduction of a 100 pesos note bearing a date in 1871 with the seal of the previous revenue system, the sealed paper makes me wonder about the possible intention to comply with the Law in its first year.. If this was the case, the stamp should have the following characteristics:

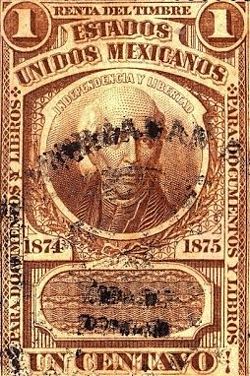

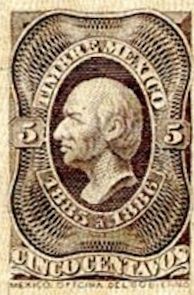

The Revenue Stamp for documents and books will be four centimeters long by three wide. In the upper part of the center it will contain the bust of the first hero of independence, Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla with the legend “Independencia y Libertad”. The lower part of the center will have a blank space to print the name of the issuing office, remaining in the center clearly legible “1872 and 1873”, or the years that correspond to the respective fiscal year. It will have an adorned border on the lower part of which the price of the stamp will be written in letters; on the sides should be put the legends “for documents and books”; at the vertices of the angles the corresponding price will be entered with a numberSHCP, bylaws of the Stamp Printing Office for Revenue and Post stamps. Art. 1. Mexico City, 31 January 1872. In: Carlos Sierra and Rogelio Martínez, El papel Sellado y la Ley del Timbre 1821-1871-1971 relación documental, México, SHCP, 1972, p. 239. .

However, it is unlikely that any of these banknotes would have met this requirement, since there are multiple references to the difficulties for the implementation of the Stamp Rent and its late start Vide Carlos Sierra y Rogelio Martínez, op. cit. appendix J pp 249-287 and “Un informe laborioso. La oficina impresora de estampillas”, El Popular, 23 September 1902; Alejandro González Prieto, El Timbre Fiscal en México, pp 45-46; Memorias de la Secretaría de Hacienda y Crédito Público, 1873-74, p. 69, but it did raise doubts about the legality of the banknotes.La Ortiga, 6 June 1872, 6 June 1872 Eventually, banknotes printed by the ABNC on a later date were stamped. On 1 December 1874, a new Revenue Stamp Law was published, this time in force as of 1 January 1875, making explicit the obligation regarding banknotes. This time, their rates were no longer referenced to those of the receipts, but to their intrinsic value and included banknotes of less than ten pesos:

| When it represents a sum that does not exceed ten pesos | $0.05 |

| Exceeding ten pesos, five cents for every fifty pesos and five cents for the fraction that is less than fifty pesos |

The rationale behind applying the Revenue Stamp Tax to banknotes was to create a level playing field because “its true purpose was to replace the coins [...] Minted coins pay a fee to the Treasury [...]. The issuance of banknotes produces nothing and their circulation makes the circulation of the currency less urgent, so that banknotes harm the Treasury and the development of mining, because they depresses the value of precious metals [and, unlike receipts ,] have no limit in their circulation.”Memorias de la Secretaría de Hacienda y Crédito Público, 1873-74, pp. 72-73

According to the 1874 law, the stamps would be printed by a special office within the Ministry of Finance (art. 79) and the latter would determine the countersigns, sizes, backgrounds, colors, issue, circulation and sale of those stamps (art. 90 ) that would change every year. In the transitory articles, a specific procedure for banknotes issued prior to the law was mentioned:

5. The banknotes issued prior to this law that represent an amount that according to it must pay the revenue stamp, will be presented to the bank or to its agents to put the respective stamps on such banknotes.

6. The banknotes issued prior to this law, which are not stamped, shall be presented to the bank or to its agents, in order to affix the corresponding stamps according to the tariff.

7. For presenting banknotes mentioned in the above paragraphs, a non-extendable term is granted from January to March 1875, during which the respective bank and its agents must pay the value of the stamps and frank them. After this period, the value of the stamps, as well as their cancellation, remain in charge of the holderSHCP, Revenue Stamp Law, 1 December 1874, in Mexican Legislation p 671.

The director of the Banco de Londres, México y Sudamérica, Thomas Horncastle, informed the Ministry that the bank was unable to meet the deadline, due to the fact that due to a forgery they had to print new banknotes to the United States and they were taken to London to be signed before reaching Mexico to replace those in circulation.“Hechos diversos”, El Foro, 3 January 187, 3 January 1875. A press release by the bank published in various newspapers on 11 June 1875 informed the holders of their banknotes the obligation to come up to the bank’s branches to redeem them as soon as possible (vide La Voz de México, 11 June 1875. The reference of sending them to the US (ABNC) is at least strange, since those of 20 to 1,000 pesos were printed there since 1866. This did not exempt the bank from complying with the new law, but it was granted an extension of up to six months. An excerpt on the works undertaken by the Stamp Printing Office from the end of 1875 in the Memoirs of the Ministry of Finance confirms the printing of those stamps when it mentions “having to print the stamp on all the banknotes of the Banco de Londres, México y Sudamérica, as you can understand there were many”cit por. Carlos Sierra and Rogelio Martínez, op. cit. pp 286 although I have not yet been able to see any banknote bearing the one of that year.

In the following pages I present the images and a brief description of each of the stamps for Documents and Books -exceptionally of the Internal Revenue- used from then onWhen I have identified that the Revenue Stamp was in fact used in Mexican banknotes in the description its catalog number is indicated among the general characteristics of the stamps, according to Mexico’s Revenue Stamps. An introduction to the revenue stamps of Mexico by Michael D. Roberts For Documents and Books it has the initials DO and for Internal Revenue initial R. Although there are exceptions in the use of colors to increase contrast, the Stamp Printing Office normally respected the colors defined for the said year and it is also added within the description. , as well as examples of banknotes with such stamps printed on them. I do not intend to be exhaustive because of the difficulty of obtaining clear images of banknotes from all banks of all denominations to show all the stamps, but I hope to give as complete an overview as possible. I do not know whether stamps on banknotes were issued uninterruptedly on all the years, since I could not find any record or banknotes from some years, especially from the early years, given the small number of issues and surviving pieces, but I include the images of the stamps in order to facilitate identification in case notes bearing stamps I did not find appear in the future.

|

||

| 1874-1875 Miguel Hidalgo 30 x 45 mm |

||

|

||

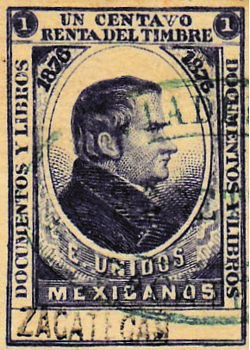

| 1876 José María Morelos 23 x 33 mm |

||

|

||

| 1877 José María Morelos 25 x 31 mm (1876 stamps validated for 1877 also exist) |

||

|

|

|

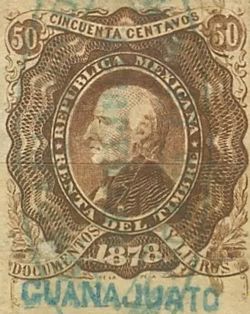

| 1878 Miguel Hidalgo 26 x 33 mm (DO#39 1¢ green) |

Banco de Londres, México y Sud América $10 |

In order to expand the fiscal base to other economic sectors, the Ministry of Finance made various amendments to the Revenue Stamp Law in the following years. In March 1876, the stamps affixed to some products, such as perfumes and drugs, were included, and the rates for banknotes were also adjusted:

| Those that represent an amount from five pesos to ten | $0.02 |

| Those that represent an amount of more than ten pesos, for every fifty pesos and for each fraction less than fifty pesos | $0.05 |

In addition to the provisions of 1874, the amended Act clarified that the stamps would be printed directly on the banknotes and did not require to be franked or re-sealed (art. 34) and that the Ministry of Finance was entitled to print them on banknotes or private documents, drafts, etc., setting the conditions for this operation (art. 115).SHCP, Revenue Stamp Law, 28 March 1876. in: Carlos Sierra y Rogelio Martínez, op.cit. p 324 y 327

The banknotes issued by the banks in Chihuahua, due to their denomination of less than five pesos, were still exempt and therefore this measure should again only have applied to the Banco de Londres, México y Sudamérica, both to the banknotes printed by the ABNC and to the new ones manufactured in England by Bradbury Wilkinson & Co (M247 and M248). Although these are rare today, in the numismatic collection of the Bank of Mexico there is a 10-peso note dated 1878 with two stamps of one-cent each with the profile bust of Miguel Hidalgo.

In the 1878-79 Memoirs of the Ministry of Finance, there is a mention of a file related to the stamps to be used on the banknotes of the Banco de Londres in circulation and for subsequent issues, but I have not been able to find its whereabouts, if it still exists, and although it is hard to understand, there is also a relation of stamp movements in the printing office which mentions the printing of at least 4,400 stamps of one and 50 cents on 2,200 notes.

Faced with the doubling in the amount of the Revenue Stamp Tax for some economic activities in 1879, Roberto Geddes, then the director of the Banco de Londres, México y Sudamérica, asked the Ministry of Finance whether these amendments would affect the banknotes and requested the exemption for those already stamped. The Ministry confirmed, but not for those issued after July 1.“El timbre y los billetes de banco”, “Gacetilla”, in El Siglo Diez y Nueve, 7 June 1879e, 7 June 1879 I have not registered any change in the tariffs and the Revenue Stamp Law of 15 September 1880, maintained the tariffs for banknotes of the previous law:

| From five to ten pesos | $0.02 |

| Exceeding ten, but not fifty pesos | $0.05 |

| If it exceeds this amount; for every fifty pesos, or a fraction | $0.05 |

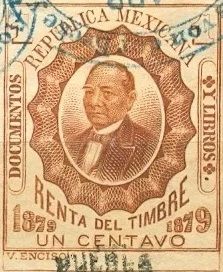

|

||

| 1879 Benito Juárez 27 x 34 mm |

||

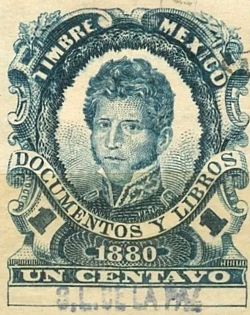

|

||

| 1880 Vicente Guerrero 28 x 34 |

||

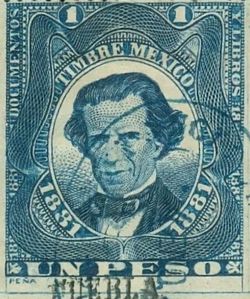

|

|

|

| 1881 Melchor Ocampo 28 x 34 mm (DO#72 1$ blue) |

Banco de Londres, México y Sud América $1,000 | |

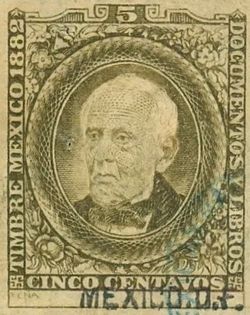

|

|

|

| 1882 Valentín Gómez Farías 28 x 35 mm (DO#75 1¢ dark blue) |

Banco de Londres, México y Sud América $5 dated 1 November 1882 |

Some remainders of the Banco de Londres, México y Sudamérica are known from this period with Documents and Books stamps from 1881 and 1882; the first of them, with a value of $1,000, has a one-peso stamp with the bust of Melchor Ocampo and the second, of five pesos, dated 1882, two stamps of one cent each, with the one of Valentín Gómez Farías. The alternation of heroes of Independence, representations of the Republic and prominent figures of Mexican liberalism like these will serve to comply with the annual change of the stamps of the regulation of the Revenue Stamp Act. Most likely, according to the 1872 regulation, the Ministry of Finance destroyed the dies every year and produced new ones. Both stamps also have an overprint (second stamp) indicating that they were issued by the Mexico City office, as was done for several years with the adhesive stamps in other years, but neither indicated yet the two years of the fiscal year.

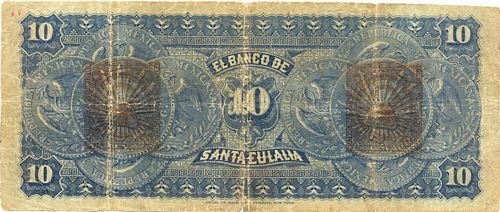

The banknotes of 1882 and 1883 of 5 and 10 pesos from the Banco de Santa Eulalia, Banco Mejicano and most likely Banco de Hidalgo del Parral also had to pay two cents of the revenue stamp, and bear two stamps of one cent each, but not so the lowest denominations, neither those of the Banco Minero Chihuahuense. If there is an issued 20-peso banknote from the Banco Mexicano, it should have a 5-cent stamp.

|

||

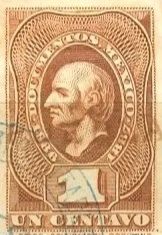

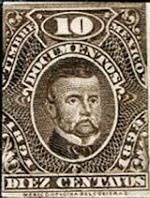

| 1883 Miguel Hidalgo 28 x 36 mm (DO#84 1¢ brown) |

||

|

|

|

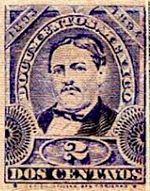

| 1883-1884 José María Mora 22 x 28 mm (DO#95 1¢ blue) (In 1884-1885 no stamps were issued) |

Banco Mejicano $10 dated 1883 | |

|

||

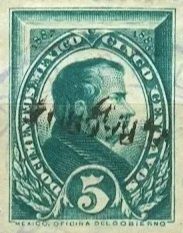

| 1885-1886 Miguel Hidalgo 18 x 28 mm |

||

|

||

| 1886-1887 Miguel Hidalgo 19 x 28 mm |

||

|

||

| 1887-1888 José María Morelos 21 x 27 mm |

As mentioned above, the banknotes of the Banco Nacional Mexicano and later those of the Banco Nacional de México had a special regime, they did not had to pay the same amounts of the Revenue Stamp but only “half a cent on the one peso to fifty pesos banknotes and one cent on those from one hundred to one thousand pesos” according to their concession contract, and therefore a special stamp was engraved for their banknotes. The same was used in both banks. Interestingly, the banknotes issued by the Nacional Mexicano were the only ones in the entire period to carry the revenue stamp on the front.

|

|

|

| ½ cent Banco Nacional Mexicano |

Banco Naxcional Mexicano $10 dated 10 February 1883 | |

|

||

| 1 cent Banco Nacional Mexicano |

||

|

||

| ½ cent Banco Nacional de México |

||

|

||

| 1 cent Banco Nacional de México |

The Banco Mercantil Mexicano also had a special stamp, as shown on the reverse of the 10 pesos dated 1882.

|

||

| 2c Banco Mercantil Mexicano |

||

|

|

|

| 5c Banco Mercantil Mexicano |

Banco Mercantil Mexicano $20 |

Nevertheless, unlike the Nacional Mexicano, this bank did not seem to have paid a preferential tariff, but the same amount of regional banks according to the Revenue Stamp Act. Thus, this denomination had to pay two cents, as proved by the single stamp of such value printed on it. It would be interesting to confirm the different values according to each.

In 1887, the Ministry of Finance again amended the Law; while maintained the rates for banknotes, it explicitly indicated the exception to Banco Nacional de México:

| From five to ten pesos | $0.02 |

| From eleven to fifty. | $0.05 |

| From fifty-one inclusive onwards, for every fifty pesos or lesser fraction | $0.05 |

| The Banco Nacional will be governed by its special concession, affixing to its banknotes, according to article 4, paragraph B of said concession, from one peso to fifty | $0.00½ |

| From fifty to one a thousand. | $0.01 |

In that same year, a new issue of the Banco de Londres, México y Sudamérica appeared, the last with that name. Contrary to previous issues, these notes no longer paid the amounts established in the Revenue Stamp Law, but the same preferential rates of the Banco Nacional de México. This may be due to the fact that in the concession contract of the Banco de Empleados, acquired in 1886 to continue operating as indicated above, there was an indirect reference to the amount of the Stamp Revenue, meaning that its banknotes would bear the stamp of the bank and a stamp of the same value stipulated for those of the Nacional Mexicano. This clause was repeated in the new concession contract in August 1889. Another interesting fact is that the stamps used in these banknotes are not those used for Documents and Books, but exceptionally those of the Internal Revenue of 15 x 62 mm with a little-known profile bust of José María Morelos in profile, young and without a bandana.

|

|

|

| (R#21 ½¢ olive brown and 22 1¢ brown) | Banco de Londres, México y Sud América $100 |

When this Bank changed its name to Banco de Londres y México, its banknotes continued paying those preferential rates and a special stamp was created. Thus, from 1889 to 1914 in the 5, 10, 20 and 50 peso notes, and also in the 1 and 2 pesos from this last year, its banknote bear a stamp of only half a cent, while those of 100, 500 and 1000 pesos, one cent.

|

|

|

| ½ cent Banco de Londres y México |

Banco de Londres y México $20 dated 2 January 1912 | |

|

|

|

| 1 cent Banco de Londres y México |

Banco de Londres y México $1,000 dated 1 October 1913 |

Banknotes dated between 1887 and 1889 of five pesos and above from the Banco Comercial de Chihuahua, Banco Mexicano, Banco Minero and Banco de Chihuahua, as well as those of the newly created banks in Durango, Nuevo León, San Luis Potosí, Sonora, Yucatán and Zacatecas from the following years also have the Revenue Stamp. With the creation of additional banks and the increasing issue of banknotes, there are more banknotes to analyze and from this moment on it is relatively easier to confirm the existence of different values of the Revenue Stamp printed on banknotes, as well as to see the annual changes to the stamps themselves. Nevertheless, the small number of high value banknotes did not allow me to confirm whether there are other values. So far, I have been able to confirm stamps of two cents on the 5 and 10 pesos banknotes; five cents for fifty pesos and ten cents for 100 pesos. Unlike previous years, those paying two cents, rather than having two one cent stamps, have only one stamp with the two cent value on them. I still need to confirm whether 500 and 1,000 pesos banknotes bear the 50 cent and 1 peso stamps.

Interestingly, unlike previous and later years, between 1886-1887 and 1892-1893, all the stamps less than one peso have the same color, making it more difficult to distinguish the denomination in worn notes.

|

|

|

| 1888-1889 Benito Juárez 21 x 27 mm (DO#145 2¢, 147 5¢ and 148 10¢ all red) |

Banco Mexicano $10 | |

|

||

| 1889-1890 Miguel Hidalgo 23 x 29 mm (DO#157 2¢, 159 5¢ and 160 10¢ all orange) |

||

|

|

|

| 1890-1891 Francisco Xavier Mina 29 x 33 mm (DO#169 2¢, 171 5¢ and 172 10¢ all green) |

Banco Comercial de Chihuahua $100 | |

|

|

|

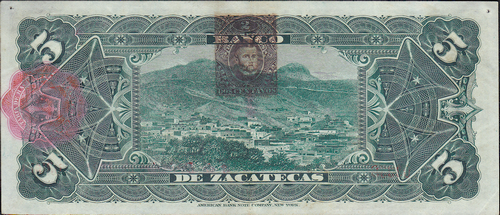

| 1891-1892 Miguel Lerdo de TejadaRichard Stevens in The Revenue Stamps of Mexico (1979) identifies the portrait as J. de la Fuente and Michael D. Roberts in Mexico’s revenue stamps says it is Sebastián Lerdo de la Fuente. I have not found anyone under this name and I do not think it is either José Antonio de la Fuente, a former Minister of Foreign Affairs or President Sebastian Lerdo de Tejada, but might be his brother, Miguel. 20 x 27 mm (DO#181 2¢, 183 5¢ and 184 10¢ all brown) |

Banco de Zacatecas $5 | |

|

|

|

| 1892-1893 Ignacio Comonfort 21 x 26 mm (DO#193 2¢, 195 5¢ and 196 10¢ all blue) |

Banco de Nuevo León $1 |

The 1893 Federal Revenue Stamp Law established new rates, but without significant changes for banknotes. It only extended the exception of the Banco Nacional de México to those banks that had specific franchises in their concessions, implicitly recognizing the preferential right of payment of the Banco de Londres y México:

| Up to twenty pesos | $0.02 |

| Exceeding this amount, for every fifty pesos or fraction | $0.05 |

| Banks that have obtained some franchises with respect to Revenue Stamp in their respective concessions will be governed by these. |

The 1 and 2 peso notes issued until 1897, as well as those of 5, 10 and 20 pesos, continued to pay a fee of 2 cents; those of 50 pesos, 5 cents; the 100 pesos, 10 cents; and, the 500 pesos 50 cents. I have not been able to see 1,000 peso bills but they must have paid a 1 peso fee.

In spite of my best effort to illustrate the most clear stamps and banknotes in the best condition, in several cases it is very difficult, if not impossible, to distinguish the value of the stamp or the stamp itself, either because of the wear or lack of contrast. This was not foreign to the Printing Office which suggested to the Ministry of Finance in 1889 to indicate to the banks for future issues the convenience of having a blank space on the reverse of the banknotes, in order to be able to print the stamps clear and clean.

|

||

| 1893-1894 José María Arteaga Magallanes 22 x 29 mm |

||

|

|

|

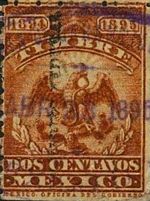

| 1894-1895 National Arms 22 x 28 mm (DO#217 2¢ yellow brown and 219 5¢ lilac brown) |

Banco de Nuevo León $20 dated 1 January 1895 | |

|

|

|

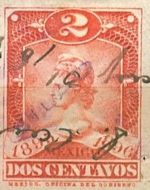

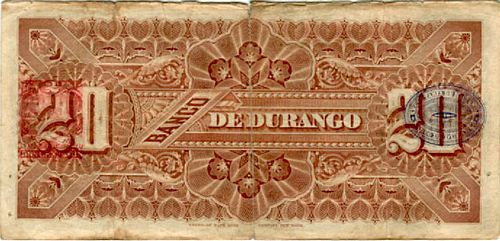

| 1895-1896 Head of Liberty (small bust) 21 x 25 mm (DO#229 2¢ vermilion, 230 5¢ blue-green, 231 10¢ blue) |

Banco de Durango $20 | |

|

||

| 1896-1897 Head of LIberty (large bust) 20 x 25 mm (DO#239 2¢ blue, 240 5¢ orange and 241 10¢ redbrown) |

Although the banks had already been complying with this obligation from what was defined in the Revenue Stamp Law, the General Law of Credit Institutions of 19 March 1897 confirmed their obligation to comply with the payment and print a stamp on the banknotes:

Article 26. No banknote shall be put into circulation without the corresponding stamp, which will be engraved on the same banknote by the Stamp Printing Office. The order will only be issued by the Ministry of Finance, after verifying that the amount of banknotes fits within the limits set for issuance in the first part of the article 16.

The Revenue Stamp Law also kept in its wording the incremental tariff every fifty pesos, as in previous years: however, from 1897 the 50, 100, 500 and 1,000 peso notes had a single stamp of 5 cents each, since the new banking law established in its article 124:

Banknotes, mortgage bonds, certificates of deposit and cash bonds that credit institutions put into circulation, as well as the checks that they issue and those that are drawn at their expense, will bear the stamp that the stamp laws determine; but with the limitation that, whatever the value of the said titles or documents, that of the stamp will never exceed five cents.

The Ministry required inspectors to sign the banknotes, not only to certify compliance with issue requirements, but also as a security measure. However, with the growing volume of banknotes in circulation, it authorized the Printing Office, in addition to the guilloche and the Revenue Stamp, to also print the facsimile of such signature on five and ten peso notes. Thus, it confirmed its intention to use both the guilloche and the Revenue Stamp as instruments to authenticate and prevent counterfeitingMemorias de la Secretaría de Hacienda y Crédito Público, 1897-1898, p 10

Banknotes continued to bear the Revenue Stamps year after year in denominations of 5 pesos onwards and it is relatively common to see all the stamps with better or lower quality and, with few exceptions, the stamps used correspond to the fiscal year. The low denomination banknotes, one peso and below, were withdrawn in the next five years.

|

|

|

| 1897-1898 National Arms 21 x 25 mm (DO#249 2¢ vermilion or rose 250 5¢ brown and 253 50¢ emerald) |

Banco Mercantil de Veracruz $50 dated 15 March 1898 | |

|

|

|

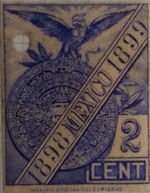

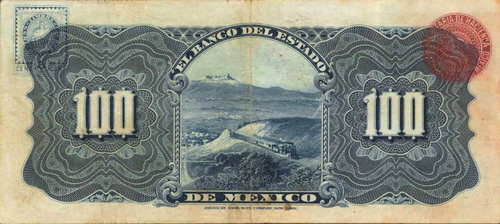

| 1898-1899 Aztec Calendar and Eagle 20 x 25 mm (DO#259 2¢ ultramarine and 260 5¢ orange) |

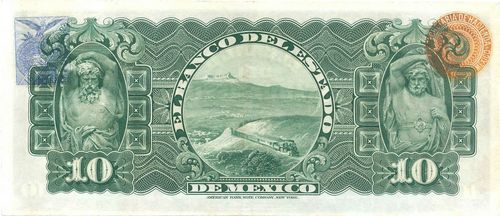

Banco del Estado de México $10 | |

|

|

|

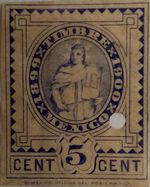

| 1899-1900 Justice 20 x 25 mm (DO#269 2¢ orange-red and 270 5¢ blue) |

Banco del Estado de México $100 dated 5 February 1900 | |

|

|

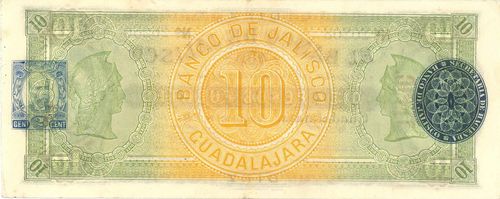

|

| 1900-1901 Matías Romero 20 x 25 mm (DO#279 2¢ blue and 280 5¢ green) |

Banco de Jalisco $10 dated 5 September 1900 | |

|

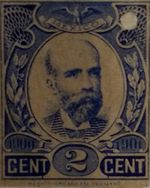

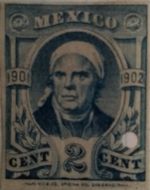

|

|

| 1901-1902 José María Morelos 20 x 25 mm (DO#289 2¢ blue green and 290 5¢ yellowbrown) |

Banco de Tabasco $5 dated 15 October 1901 | |

|

|

|

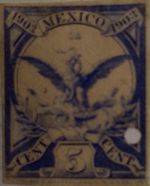

| 1902-1903 National Arms 20 x 25 mm (DO#299 2¢ green and 300 5¢ ultramarine) |

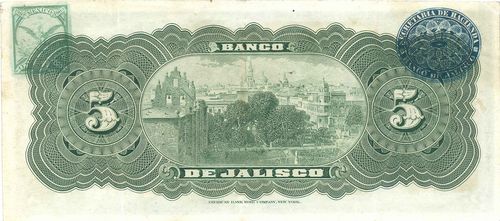

Banco de Jalisco $5 dated 5 May 1903 | |

|

|

|

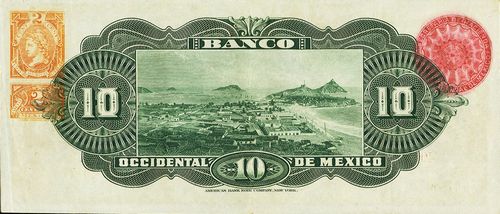

| 1903-1904 Liberty 20 x 40 mm (R#226 2¢ orange and 227 5¢ brown) |

Banco Occidental de México $10 dated 1 March 1904 | |

|

|

|

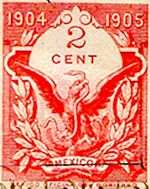

| 1904-1905 National Arms 20 x 25 mm (DO#323 2¢ rose and 324 5¢ violet-brown) |

Banco Mercantil de Veracruz $5 | |

|

|

|

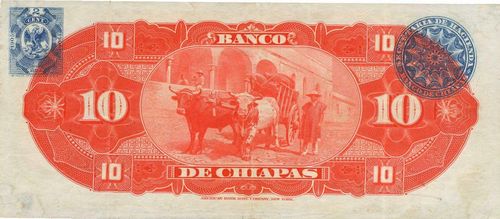

| 1905-1906 National Arms 20 x 25 mm (DO#335 2¢ blue and 336 5¢ green) |

Banco de Chiapas $10 dated 5 May 1906 |

Interestingly, in the fiscal year 1903-1904 rather than using the Books and Documents, the Revenue Stamps printed on banknotes were the Internal Revenue ones, with the bust of the republic, with the stub (talón) included.

The last Revenue Stamp Act applicable to banknotes was the one issued on 1 June 1906. There was no change in the rates applicable to these documents:

| Up to twenty pesos | $0.02 |

| Exceeding this amount, for every fifty pesos or fraction | $0.05 |

| Banks that have obtained some franchises with respect to Revenue Stamp in their respective concessions will be governed by these. |

The 1907 financial crisis produced a relatively low number of issues in 1908 and 1909, but these resumed and increased in the following years.

|

|

|

| 1906-1907 Miguel Hidalgo 20 x 25 mm (DO#347 2¢ orange-red and 349 5¢ blue) |

Banco de Aguascalientes $50 dated 1 May 1907 | |

|

|

|

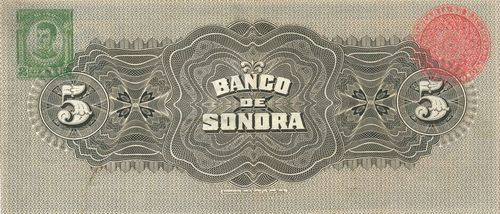

| 1907-1908 Ignacio Allende 20 x 25 mm (DO#360 2¢ green and 362 5¢ brown) |

Banco de Sonora $5 dated 1 October 1907 | |

|

|

|

| 1908-1909 National Arms 20 x 25 mm (DO#373 2¢ red brown and 375 5¢ blue) |

Banco de Nuevo Leon $50 | |

|

|

|

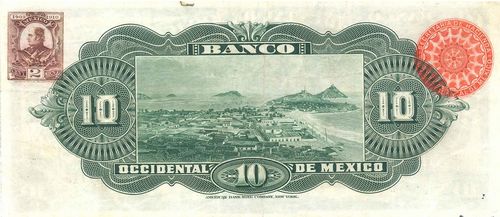

| 1909-1910 José María Morelos 20 x 25 mm (DO#386 2¢ brown and 388 5¢ green |

Banco Occidental de México $10 dated 16 October 1909 | |

|

|

|

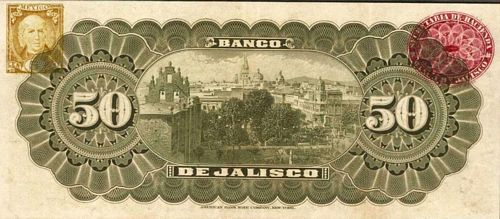

| 1910-1911 Miguel Hidalgo 20 x 25 mm (DO#399 2¢ slate and 401 5¢ bistre) |

Banco de Jalisco $50 dated 5 January 1911 | |

|

|

|

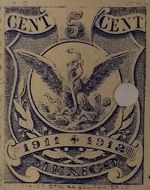

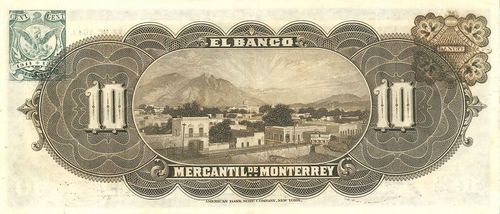

| 1911-1912 Escudo nacional 20 x 25 mm (DO#413 2¢ slate and 415 5¢ blue) |

Banco Mercantil de Monterrey $10 dated 27 July 1911 | |

|

|

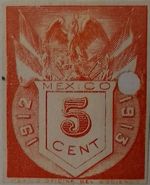

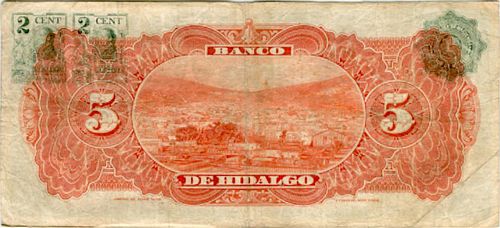

|

| 1912-1913 Escudo nacional 20 x 25 mm (DO#426 2¢ green and 428 5¢ vermilion) |

Banco de Durango $5 dated 18 June 1913 |

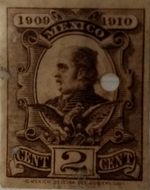

On 11 October 1913 Victoriano Huerta granted himself extraordinary powers under which he issued various decrees with the aim of obtaining resources to maintain his government afloat and fight Constitutionalist forces. On 5 November he suspended the obligation of the issuing banks to redeem their banknotes in cash, that is, it imposed their compulsory circulation and, on 19 November, he allowed these banks to also issue 1 and 2 peso banknotes and days later also 50 cents notes, although only the Banco de Jalisco managed to put the latter into circulation. Although it is not explicitly mentioned in the decree, the one and two peso bills of around a dozen banks put into circulation between the end of 1913 and 1914 bear a one cent Revenue Stamp. Most of them bear the stamp of Mariano Matamoros, but those dated from July 1914 such as that of the Banco de Coahuila (M175), Guanajuato (M348a) and the Banco Minero de Chihuahua (M130d), even some of the latter dated in June, also were printed with the one with the arms and child but it is not easy to distinguish.

|

|

|

| 1913-1914 Mariano Matamoros 20 x 25 mm (DO#438 1¢ olive, 439 2¢ green and 441 5¢ orange) |

Banco de Jalisco $10 dated 26 March 1914 | |

|

|

|

| 1914-1915 Arms and child 20 x 25 mm (DO#452 2¢ green and 454 5¢ orange) |

Banco Ociental de México $20 dated 1 April 1914 |

A lesser-known decree, at least among the numismatic community, was also published on 19 November, by which Huerta created and increased various taxes.Diario Oficial, 19 November 1913 pp 158-160 According to the recitals, these measures sought to address the increase in expenses, the depreciation of the currency, the increase in debt service and would be reversed or eliminated when circumstances permitted. Article 1 doubled the tariffs indicated in art. 14 of the Revenue Stamp Law, among which banknotes were included. According to the transitory articles, when stamps were printed on stocks, bills, bonds and other documents, the fee would be paid on the date of request for the printing of said stamps, regardless of whether the date of said documents was earlier. This situation may explain why two stamps of two cents each appear on the 5-peso banknotes issued by the Banco de Hidalgo dated 1 December 1913

and in those of 5 and 20 pesos from the Banco Oriental de México on 3 January 1914 instead of just one.

However, not all the banknotes from that time fall into this case; those of 1 peso of the Banco de Yucatán dated 30 November, those of the Banco Nacional de México of 6 December, have only one like almost all those issued in 1914 including the 5 pesos of the Banco de Hidalgo of 21 April 1914. However, the Banco Oriental notes represent an even more interesting case, given that there are 5 and 20 peso notes with one and two stamps and other denominations of the same date with only oneAfter a careful review of the banknotes in the numismatic collection of the Banco de México I managed to see that two stamps are seen on five peso banknotes within the 410,000 to 509,000 serial number range, and beyond 510,000 they normally only have one stamp (it must be said that there are few outliers). Likewise, in the 20 pesos banknotes, there are two stamps on those ranging 45,000 to 53,000, and only one stamp beyond 55,000 (to 69,000). Probably, a counter order arrived when they were sealing those notes.. Surely the measure was quickly reversed although I have not yet found a reference to it.

In the following years, during the Revolution, there were multiple issues of paper money, issued normally only backed by the political force of the military authorities in turn, however there were also commercial issues that paid the Revenue Stamp, not printed directly on them like banknotes, but with adhesive stamps on the reverse, but those pieces merit a separate study.

References:

Genaro García, Diccionario de la renta federal del timbre, comprende fielmente todas las leyes y disposiciones administrativas urgentes sobre dicho impuesto / arreglo. Mexico, Herrero Hnos., 1900.

Gonzalez Prieto, Alejandro, El Timbre Fiscal en México, Mexico, SHCP, 1998

Ludlow, Leonor, López-Bosch, Cedrian and Chapa, Arturo. Valores de la Nación, Memoria histórica de la Tesorería de la Federación, Mexico, SHCP, 2017

Roberts, Michael D, Follansbee, Nicholas; Barr, William, et ed., Mexico’s Revenue Stamps, Mexico-Elmhurst Philatelic Society, International, 2011

Sierra, Carlos and Martínez, Rogelio, El papel Sellado y la Ley del Timbre 1821-1871-1971 relación documental, Mexico, SHCP, 1972

(based on articles in the USMexNA journals. In these Cedrian thanked Jaime Benavides, Luis Gómez-Wulschner, Itzel Hidalgo, Ricardo de León, Raúl Martínez, Carlos Medina, Simon Prendergast, Alberto Rodríguez, Siddharta Sánchez, for their support in providing illustrations as well as their kind comments and suggestions).