La Fábrica “El Tunal”

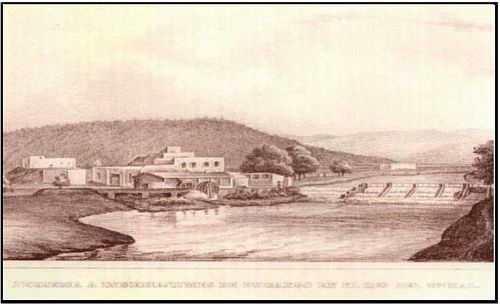

The cotton cloth factory, La Fábrica de Hilados y Tejidos “El Tunal”, also called “La Providencia”, was situated on the banks of the river Tunal, in El Pueblito, now virtually a suburb of the city of Durango. The factory was founded by the German, Hermán Stahlknecht, and the Spaniard, José Fernando Ramírez Alvarez, in 1837.

José Fernando was born in Hidalgo del Parral, Chihuahua, on 5 May 1804, studied at universities in Durango and Zacatecas and graduated as a lawyer in 1832. He was Deputy for Durango in 1833 and 1842, and from 1841 to 1852 held various public appointments: Secretario de Gobierno, Presidente of the Tribunal Mercantil and of the Junta de Instrucción Pública, Director of the Periódico Oficial, Senator for two sessions and Ministro de Relaciones Interiores y Exteriores. Antonio López de Santa Anna appointed him to the Supremo Tribunal de Justicia de la Nación, but he was exiled to Europe in 1854 for supporting the Plan de Ayutla, which sought to remove the dictator Santa Anna and led to the War of Reform. He returned in March 1856. Under Maximilian he again occupied the Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores and served as president of the Imperial Council and in 1867 he was a magistrate of the Supremo Tribunal de Justicia del Imperio. When the Republic was restored, he returned to Europe and died in Bonn, Germany, on 4 March 1871. A scholar and bibliophile, he was instrumental in saving many of the books from the old convent libraries as well as pre-Hispanic texts.

In 1850, by which time the factory was under the proprietorship of the firm of Stahlknecht and Lehmann, it employed supervisors from New England and several hundred Mexican women. The Stahlknecht family, through the company Stahlknecht y Compañía, was also involved in banking.

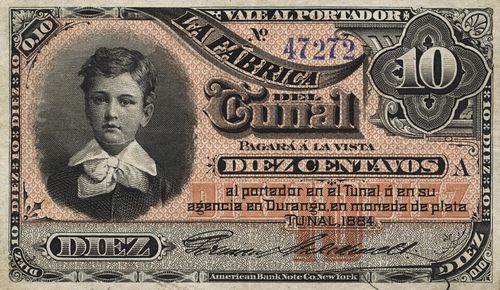

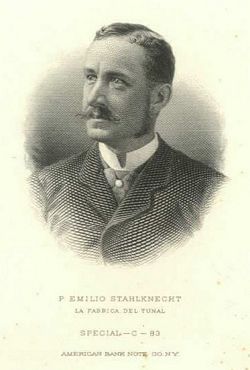

On 1 April 1884 the factory’s owner, P. Emilio Stahlknecht, placed an order with the American Bank Note Company for a series of four denominations of company scrip with which to pay his workersABNC, folder 1524, La Fábrica del Tunal (1931-1932).

| Series | from | to | total number |

total value |

||

| 10c | A | 00001 | 50000 | 50,000 | $ 5,000 | |

| 25c | A | 00001 | 40000 | 40,000 | 10,000 | |

| 50c | A | 00001 | 40000 | 40,000 | 20,000 | |

| $1 | A | 00001 | 20000 | 20,000 | 20,000 | |

| $55,000 |

M714a 10c La Fábrica del Tunal

M714a 10c La Fábrica del Tunal

M715a 25c La Fábrica del Tunal

M715a 25c La Fábrica del Tunal

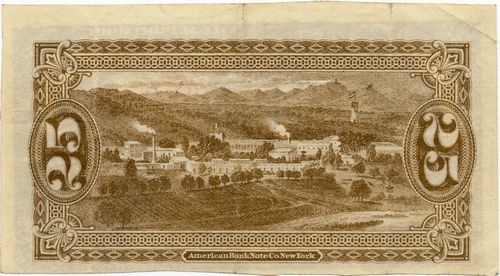

M716a 50c La Fábrica del Tunal

M716a 50c La Fábrica del Tunal

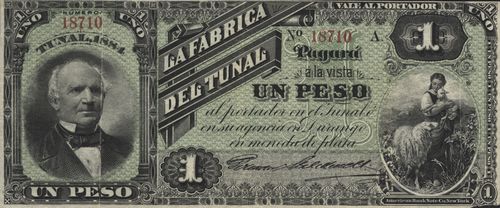

M717a $1 La Fábrica del Tunal

M717a $1 La Fábrica del Tunal

The face of the notes carried portraits of members of the owning families – the original founders, Hermán Stahlknecht and José Fernando Ramírez Alvarez on the 50c and $1 notes, P. Emilio Stahlknecht (C 83) himself on the 25c and the young Germán Fernando Stahlknecht, born on 10 April 1876, appears on the ten centavos.

The ABNC also three stock vignettes: a plough and a horse's head, entitled "Horse Head No. 1" (#36), on the 50c and a young shepherdess, who also appears on the 25c Banco Mejicano of Chihuahua, on the one peso.

The ABNC also three stock vignettes: a plough and a horse's head, entitled "Horse Head No. 1" (#36), on the 50c and a young shepherdess, who also appears on the 25c Banco Mejicano of Chihuahua, on the one peso.

Horse Head No. 1

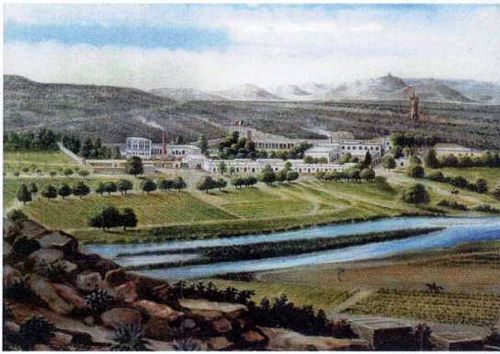

The reverse of all values had a vignette of the factory, based on a painting by Leon Trousset which is now in the Susan Dowd Family Collection.

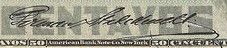

The printed signature is of [ ] Stahlknecht[identification needed].

| [ ] Stahlknecht |  |

The Mexican government passed its Código de Comercio on 15 April 1884. Chapter XII referred to “Los Bancos”. Articles 954 to 955 stated that in future federal authorisation would be needed to establish any bank (bancos de emisión, circulación, descuento, depósitos, hipotecarios, agrícolas, de minería o con cualquier otro objeto de comercio). Articles 957 and 958 laid down that they would have to be joint stock companies (sociedades anónimas) with at least five founder members, and a minimum share capital of $500,000, with at least half fully paid up. Only banks conforming to the law could issue notes payable to the bearer on sight: note issue could not exceed paid-in capital: fixed cash reserves were required, and all banknotes other than those of El Banco Nacional de México were taxed at 5% of their value. A final article stated that existing banks could not continue operating unless they subjected themselves to the Act within six months.

On 10 January 1885 the District Judge (Juez de Distrito) complained to the Secretaría de Hacienda about the Fábrica del Tunal’s issue. The Secretaría ordered the local Jefe de Hacienda to investigate and take any action in accordance with the recent Código de Comercio. On 9 February the Jefe de Hacienda reported that, in accorance with article 979 of the Code, it had fined the company $25.22 for an issue of $252.20 and told them to withdraw the vales.

Then, on 18 May, the Secretaría entered into a contract with Stahlknecht y Compañíathe contract was between the Secretariá de Hacienda en representación del ejecutivo de la Union, and José M. Ramirez (El Siglo Diez y Nueve, 22 May 1885) for an issue of vales al portador, for the single, exclusive use for wages and salaries of workers and employees of the “El Tunal” factory. The contract still had to be approved by CongressMemoria de la Secretaría de Hacienda correspondiente al ejercicio fiscal de 1884 á 1885, México, 1885.

During the revolution

In October 1913 the revolutionary government was said to be going to reopen the factory and was already sourcing cottonEl Demócrata, Durango, 12 October 1913.

M1453 50c La Fábrica del Tunal used by Brigada Ceniceros

M1453 50c La Fábrica del Tunal used by Brigada Ceniceros

M1454 $1 La Fábrica del Tunal used by Brigada Ceniceros

M1454 $1 La Fábrica del Tunal used by Brigada Ceniceros

Some 50c and $1 notes are known as REVALIDADO or with a validation on the back ‘EJERCITO CONVENCIONISTA – D. DEL N. BRIGADA CENICEROS – FUERZA DEL MAYOR – PRIMITIVO ESPINOSA’ (Ceniceros Brigade of the Conventionist Army, Division of the North, Force of Major Primitivo Espinosa).

The Brigada Ceniceros, led by General Severino Ceniceros, was part of Villa’s División del Norte. Ceniceros was born in Cuencamé, northern Durango, in 1880 and with his fellow townsman, General Calixto Contreras, was an early adherent to the revolutionary cause - the two of them were responsible for the famous MUERA HUERTA coin. Primitivo Espinosa, also from Cuencamé, was related to Conteras and, though a wealthy merchant, agitated for agrarian reform. So the location and personnel fit.

One piece of evidence is a telegram from the state of Durango to the Visitador de los Municipios de Jalisco, on 14 December 1914, that notes of the Fábrica Tunal had no valueADUR, Fondo Secretaría General de Gobierno (Siglo XX), Sección 6 Gobierno, Serie 6.7 Correspondencia, caja 7, nombre 36 and ADUR, Libro Copiador 278, Telegramas 13 August 1914 - 23 April 1915, p234 . They surely were not responding to a query about 30-year-old company scrip.

Other mentions attest to their (widespread) use. An item from La Opinión, a Mexico City newspaper, of 22 December 1914, headlined “Three individuals detained for circulating counterfeit notes”, recorded that a Carlos Maciel, Raúl Ugarte and Constantino García were being held in Mexico City, as the key to the counterfeiting of an enormous quantity of El Tunal notes. These notes had circulated widely in Aguascalientes, during the time of the Convention, (if strictly literal, from 10 October until 9 November 1914), and had now appeared in the capital. Maciel had been picked up with a wad of brand new notes, which he said he had got from the former Carrancista captain Ugarte, who in turned claimed he had been given them by a Carranista jefe in Aguascalientes. García, owner of the El Imperio cantina, was arrested with the note illustrated in the article and thirty-five others were found in his cash register. He also claimed that he received the notes from Ugarte. Obviously, the notes are not actually counterfeits, merely worthless, and one hopes that the accused did not suffer too great a penalty. But the article does confirm that the notes were in use in 1914, over quite a wide area, and, originally, without the need for any revalidationLa Opinión, Mexico City, 22 December 1914.

Another piece of evidence is an article in the newspaper La Convención of 29 December 1914 on the revalidation ordered for Carrancista notes which states that the only notes that should be refused are those issued by the federal forces in Guaymas, Monterrey and Saltillo and those issued by private companies, such as El TunalLa Convención, 29 December 1914.

A $1 Fábrica del Tunal note is listed in the balance sheet (Corte de Caja) of the Registro Civil of Santa Rosa, Querétaro, on 26 November 1916AQ, Fondo Poder Ejecutivo Sec 2ª Hacienda C-5 Año 1916 Exp. 69.

[The 1906-1916 Accounts of the Fábrica are in box 15, folder 3 of the David W. Walker Papers , University of Chicago]