Esteban Cantú

Born in 1880, José Esteban Cantú became known for single-handedly keeping all of northern Baja California out of the Mexican Revolution. As a major in the Mexican army Cantú was Chief of Line in Mexicali in 1911. By August 1912, he had his own cavalry regiment. During the Mexican Revolution, Cantú and his men fought off revolutionists in several skirmishes along the Colorado River and its confluence with the Gila and also turned back a handful of revolutionary soldiers at Las Islitas on 14 November 1913, effectively ending military action against the Federals in the northern area.

Born in 1880, José Esteban Cantú became known for single-handedly keeping all of northern Baja California out of the Mexican Revolution. As a major in the Mexican army Cantú was Chief of Line in Mexicali in 1911. By August 1912, he had his own cavalry regiment. During the Mexican Revolution, Cantú and his men fought off revolutionists in several skirmishes along the Colorado River and its confluence with the Gila and also turned back a handful of revolutionary soldiers at Las Islitas on 14 November 1913, effectively ending military action against the Federals in the northern area.

In recognition of his military prowess Villa had Cantú, then a Mexican Army colonel, keep his military command. By 1 January 1915 Cantú had successfully become the political leader as well, a fact confirmed by Villa in a 20 January 1915 telegram which appointed Cantú as the political and military chief, a position he would hold for 5½ years.

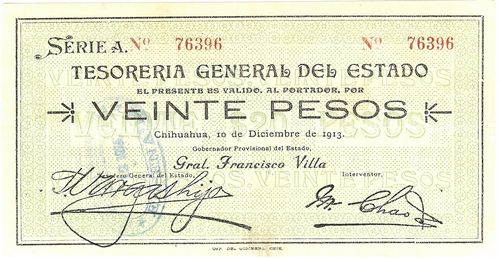

In October 1914 it was reported that more than $300,000 in Villista paper money had been sent to Baja California. The Chinese shopkeepers in Ensenada were closing their businesses rather than accepting this moneyPrensa, 11 October 1914.

Some early Constitutionalist issues (Monclova, sábanas and Ejército Constitucionalista) were revalidated by the Jefatura Política in Ensenada. Two resellos are known:

1) A 49mm blue oval stamp with ‘JEFATURA POLITICA DEL DISTRITO NORTE – ENSENADA’ and date in centre.

2) ‘JEFATURA POLITICA DEL DISTRITO NORTE DE LA BAJA CALIFORNIA, ENSENADA’[image needed]

Cantú took over a land devastated by war and left bankrupt by his predecessors. To begin the reconstruction, he levied trade duties and imposed personal taxes. He began the long process of economic development of the Mexicali Valley. He opened schools even in the smallest villages; encouraged industry, agriculture and commerce; and started important infrastructure, including drainage, roads, streets, electricity, and bridges. He also built a road to link Mexicali with Tijuana.

Cantú tried to remain neutral when Carranza became President but kept ignoring federal orders. One sourceSD papers, No. 274, 812.00, NA, W. F. Fullam to the Secretary of the Navy, 29 May 1918 notes that the territory did not pay one single peso in taxes to Carranza’s treasury, although another Antonio Ponce Aguilar, El Coronel Esteban Cantú en el Distrito Norte de Baja California, 1911-1920, Mexicali, 2010, p. 99 holds that Cantú frequently sent taxes to the federal government. A more serious affront was Cantú’s refusal to use Mexican coinage or currency of any vintage, using that of the United States instead. As paper money had suffered from inflation, in January 1915 Cantú ordered[text needed] that all commercial transactions and salaries were to be paid in gold pesos or United States dollars at the rate of two pesos to the dollar: he reiterated this rate in his circular of 21 June. When Joaquín Aguirre Berlanga was sent to the Northern District to introduce the new currency of the central government, Cantú refused to accept it. Thus the United States dollar remained the medium of exchange during the Cantú years.

In October 1915 Cantú sent a circular to all the banks, authorities, and principal merchants of Calexico informing them that he no longer recognized the Convention government and that he intended to remain neutral regarding the conflict on the mainland until the last minute, when he would recognize the government that emerged from the civil war raging between Villa and Carranza.

In 1920 the new President de la Huerta appointed Baldomero Almada governor but Cantú refused him entrance, and finally the central government had to resort to force, sending troops under the command of General Abelardo L. Rodríguez.

One historian writes "Accustomed to paying his troops and employees in gold, Cantú now began to print paper money because his government was so short of cash. Workers found the currency unacceptable; merchants closed their shops rather than accept the worthless paper, and Cantú found it increasingly difficult to recruit new troops for his army."Joseph Richard Werne, Esteban Cantu and the Mexican Revolution in Baja California Norte 1910-1920, Fort Worth, Texas, 2020, p. 101

In July 1920, given the loss of support and revenue Colonel Cantú abandoned his post and went into exile in the United States.