Forced loans

Forced loans were frequently exacted by the state or factions within the state. It is necessary to distinguish such forced loans from extraordinary levies. The latter were just additional taxes whilst the former were nominally intended to be repaid (though many who were subject to such 'loans' did not expect to see their money again), occasionally bore interest and usually gave the lender a receipt that could be offset against future dues or taxes. Such documents, though they usually did not have printed denominations and were made out to a particular individual, were frequently transferable and, if the issuer retained or gained a position of power, of value.

The state government was already in debt by the 1860s and in his governor's statement in 1861 Terrazas reported the large claims on the state's resources included loans (not necessarily forced) made by various individuals during the recent stormy pastDiscurso of Governor Terrazas, 18 September 1861. However, the period of the French intervention and the various revolts in the 1870s were particularly fertile times. The following list is no doubt not exhaustive.

The French intervention

During the French intervention Terrazas levied forced loans of $40,000 on 18 May 1862La Alianza de la Frontera, 22 May 1862. The sum was to be divided between the districts thus:

Iturbide $8,000

Hidalgo 6,600

Mina 2,000

Rosales 1,800

Rayón 1,600

Allende 2,000

Guerrero 2,000

Bravos 2,000

Matamoros 2,000

Jimenéz 1,000

Victoria 2,500

Abasolo 1,600

Balleza 2,000

Camargo 2,500

Galeana 1,200

Aldama 1,200, $21,000 on 3 September 1862La Alianza de la Frontera, 4 September 1862. The sum was to be divided between the districts thus:

Iturbide $4,000

Hidalgo 3,600

Mina 1,000

Rosales 1,000

Rayón 800

Allende 1,100

Guerrero 1,100

Bravos 1,000

Matamoros 1,100

Jimenéz 600

Victoria 1,200

Abasolo 800

Balleza 1,000

Camargo 1,500

Galeana 600

Aldama 600, $33,000 on 16 May 1863La Alianza de la Frontera, 16 May 1863. The division was:

Iturbide $7,200.00

Hidalgo 7,200.00

Mina 2,400.00 (Guadalupe y Calvo 1,500, Morelos 800, Batopilas 100)

Rosales 2,400.00

Rayón 800.00

Allende 2,100.00

Guerrero 1,300.00

Bravos 1,000.00

Matamoros 1,000.00

Jiménez 600.00

Victoria 800.00

Abasolo 700.00

Galeana 600.00

Aldama 500.00

Camargo 4,000.00

Balleza 600.00 and $99,000 on 25 June 1863La Alianza de la Frontera, 25 June 1863. Including $7,200 from Mina but with a rebate of $4,500 (Guadalupe y Calvo $2,814; Morelos $1,500, Batopilas $186).

Angel Trias levied a forced loan of $10,000 on seventeen private citizens in the capital (including Luis Terrazas, Mariano Sáenz, Félix Maceyra and Antonio Asúnsolo) in October 1864. The loan was to have been repaid within three monthsEl Republicano, 29 October 1864. The full list was:

José Cordero $3,000

Viuda de Olivares $1,600

Luis Terrazas $1,000

Mariano Saenz $1,500

Félix Maceyra $350

Antonio Asúnsolo $250

Juan M. Asúnsolo $100

Avila y Jurada $400

Leonardo Siqueiros $100

Salido y Puchi $500

Juan Mandri $500

Rafael Gameros $300

Joaquin Campa $100

Faudoa y Zabiata $50

Berardo Rivilla $100

Mariano Maceyra $50

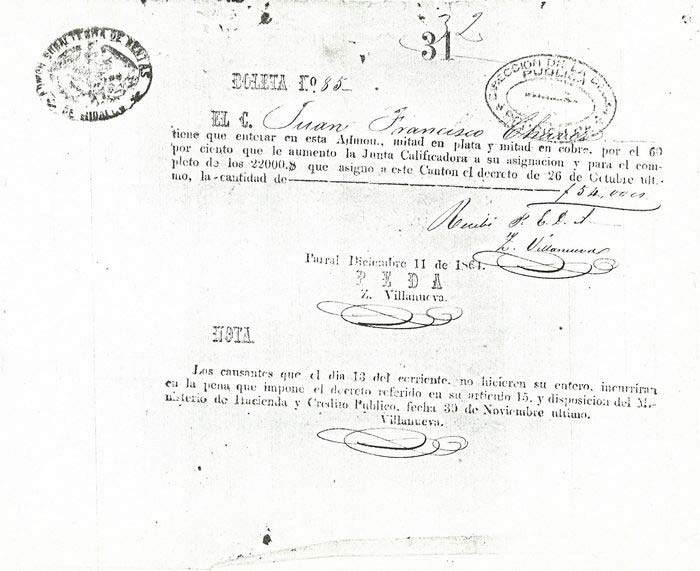

Miguel Betancourt $100. Angel Trias also imposed a contribution of 100,000 pesos on the stateibid.. There survives a receipt from Parral dated 11 December 1864 and signed by Z. Villanueva.

The receipt is a demand, numbered 'Boleta No. 85', stating that the person named has to hand over to the Administrador de Rentas, half in silver and half in copper, his share of the $22,000 levied on the canton by the Junta Calificadora by the decree of 26 October[text needed], with a hand-written acknowledgement of receipt..

There was a forced loan by the Junta Calificadora (Assessment Board) in Guadalupe y Calvo on 7 March 1865Francisco Almada, Guadalupe y Calvo, Mexico, 1940.

Remedios Meza

On 9 September 1865 General Remedios Meza, with the 2a Brigada de Durango asked for a forced loan (prestamo extraordinario) of $15,000 from Guadalupe y Calvo, which the Jefe Político managed to get reduced to $9,000. They handed over $2,500 from federal funds, and $2,000 from the decree of 7 June, with the rest distributed amongst the businesses and inhabitants of Guadalupe y Calvo, with the condition that the State of Durango would repay it. However, when the holders of the documents issued by Meza later sought reimbursement they were unsuccessfulibid..

On 18 June 1871 the rebels Francisco Cañedo, Doroteo López and Adolfo Begne captured Guadalupe y Calvo and imposed a forced loan of ten thousand pesos. They retreated to Sinaloa a week later.

The rise of Porfirio Díaz

In July 1872 the Porfirista Donato Guerra captured Chihuahua City and imposed a forced loan of 150,000 pesos. Governor Terrazas had retreated to Guerrero, from where he sent Gabriel Casavantes and José Valenzuela out to the Sierre Madre mining districts with instructions to raise loans for the cost of resistance under the nominal guarantee of the State Treasury. The next month, when Guerra reached a peace agreement with Terrazas, it was decided to hand the matter of Guerra's loan over to the federal authority in Mexico City to decide how to resolve the affair.

In 1876, when President Sebastian Lerdo announced that he was to seek re-election, the disappointed Porfirio Díaz again rose in revolt. In Chihuahua Angel Trias declared for Díaz, besieged the state capital and took Governor Ochoa prisoner. The Tuxtepecanos held Chihuahua City from 2 June to 19 September. In July Trias, as Military Commander, levied a forced loan of $56,000 on the principal citizens and issued certificados, which were to be accepted for tax purposes by state and federal officesBoletin Militar, 1 July 1876. The list was:

Nestor Armijo $2,500

Antonio Asunsolo 2,000

Henrique Muller 2,000

José de la Luz Corral 2,000

Luis Faudoa 2,000

Ketelsen y Degetau 2,000

Francisco Macmanus 2,000

Félix Francisco Maceyra 2,000

Enrique Norwald 2,000

González Treviño Hermanos 2,000

Luis Terrazas 2,000

Nicolás Armijo 1,500

Banco de Chihuahua 1,500

Gosch y Markt 1,500

Guillermo Hagelsieb 1,500

Pedro Zuloaga 1,500

Ramón Luján (for self and Senora Dolores Alvarez) 1,500

Walterio Henry 1,500

Miguel Betancourt 1,000

Agustín Cordero Zuza 1,000

Domingo Leguinazábal 1,000

José Félix Maceyra 1,000

Horcasitas Hermanos 1,000

Gustavo Moye 1,000

Mariano Puchi 1,000

Casa de Mariano Sáenz 1,000

Miguel Salas 1,000

Jesús María Ortiz 800

Viuda de Chabre e hijos 800

Juan Manuel Asúnsolo 600

Grandfan y Audetal 600

Eduardo Fricth 500

Fuentes y Bezaury 500

Testamentaría de D. Francisco Celis 500

Compañía Americana 500

Carlos Moya 500

Francisco Mollmaun 500

Testamentaría de Mariano Maceyra 500

Dr. Jesús Muñoz 500

Treviño y Tejeda 500

Pedro Mignagoren 500

Lic. Antonio Jáquez 400

Guillermo Moye 400

Miguel San Martín 400

Dionisio Trías 400

José María Sini 350

Ignacio Uranga 300

Genaro Chavéz 300

Bermúdez Hermanos 300

Testamentaría de Da. Jesús Porras de González 300

Luciano Delgado 250

Viuda de Bustamante e hijo 250

Viuda de Felipe Siqueiros 200

Da. Concepción Gabaldón 200

Francisco Marquéz 200

Eduardo Ptacnick 150

Concepción Orcillo 100

Juan Chavéz 100

Da. Concepción Maceyra 100

Pedro Olivares 100

Miguel Sepúlveda 100

Doña Josefa Terrazas 100

Lorenzo Martín del Campo 100

Bartolo Guereque 50. Terrazas was upset by his own assessment of $2,000, slipped away to his haciendas and began to organise the resistance.

Enrique Müller

Enrique Müller also refused to pay the 3,500 pesospresumably the $2,000 in his own name and the $1,500 levied on the Banco de Chihuahuaassessed in Trias' levy, escaped to the countryside and from his hiding place aided the loyal troops. It was Müller’s misfortune to fall into the hands of a band of rebels commanded by Colonel Delgado who took his prisoners to El Paso del Norte (now Ciudad Juárez). Müller sought the protection of the American military commander at El Paso and the latter threatened to bombard the Mexican town unless Müller was released, which by the way was not done though fortunately the threat went unfulfilledMrs. Müller through some friends applied to Colonel Andrews at Ft. Davis, who responded by (SD papers, letter Louis H.Scott to , 25 January 1877. Scott had not yet received his Exequatur and so was not formally recognized as the U.S. consul in Chihuahua). The New York Herald, however, published an article by John Watson Foster, then United States Minister to Mexico, relative to the Müller case with the alarming headlines, “The Turks of America. Mexico and its Abuses upon American Citizens. A Government of Thieves.”

When Müller was arrested, he was in company with four other gentlemen, all of whom claimed to be citizens of the German Empire. These four German citizens were held for a few days and then allowed to leave, leaving only a portion of their arms and a small sum of money which they happened to have on their persons. Müller, however, was kept a close prisoner for more than a month, dragged over rough mountains and across a desert country, placed in their first ranks under the fire of his friends, and obliged to submit to every iniquity which they could possibly offer to him. They even stole his saddle and his boots, and then after treating him in this manner, exacted $3,500 for his ransom. When the kidnapping was reported to Mexico City, Díaz sent a message cautioning the commanding general against further outrages against Germans, but did not mention Americans.

When Müller was released after paying the ransom, the first thing the state government did was to demand a ‘loan’ of $4,000, which Müller did not expect to be repaid.

The United States government, through its diplomatic channels, investigated the Müller affair and the Mexican authorities were exonerated by the Hon. J. C. Houston, American Vice-Consul in Chihuahua City, on 3 August 1877Memorias de Hacienda 1878-1879, México, 1880.

Francisco Macmanus and Sons and other Americans

During the Tuxtepecano occupation Americans were forced to pay many thousand dollars in money, and a refusal to pay was followed by immediate imprisonmentSD papers, letter Louis H. Scott to Hamilton Fish, Mexico, 23 January 1877. The Department of State received the letter on 10 February 1877 and acknowledged it on 13 July. Scott was to inform the Department of all such proceedings and take the depositions of the sufferers for future use . Acting governor Samaniego surrendered Chihuahua City to the Porfirista General Juan B. Caamaño on 5 February 1876. Later that same day General Angel Trias and his forces entered the city. Apparently there was some disagreement between the two generals and Trias soon tendered his resignation to Caamaño and retired to private life. Caamaño needed money for his troops, and learning that there was a lot of merchandise lying at Presidio del Norte, told the merchants, the Treviño Bros, Gustavo Moye, Henry Nordwald and Francisco Macmanus and Sons, that if they introduced their goods and paid him the duties, he would not have to resort to a forced loan. He stated that he would send an escort of two hundred men and bring in the (wagon) train and have them passed by the Custom House officer in Chihuahua, as there was no organized Custom House force in Presidio at the time. The merchants agreed and paid about $30,000,according to Scott in his report of or $10,000 from Nordwald and Macmanus, according to his letter of 9 July 1877, the money was used to pay off some of Caamaño’s troops, and the train started for Chihuahua on 19 February. They had journeyed one or two days when Trias arrived and ordered the train back to Presidio. Trias demanded that the goods were passed through the Presidio Custom House before proceeding to Chihuahua, and that the owners hand over $6,000 as part payment of the duties to be paid.

At the time they paid Caamaño the merchants believed he had the authority of the Díaz government, but on 14 February Jose Eligio Muñoz arrived in Chihuahua as provisional governor and one of his first statements was to the effect that he would not recognize the transactions made by Caamaño and that he would compel the merchants to pay the duties a second time. Caamaño under these circumstances would not hand over the government to Muñoz and Trias, who, finding themselves foiled, took possession of the train and demanded that the merchants pay the duties againSD papers, letter H. Nordwald and F. Macmanus and Sons to John W. Foster, 5 March 877. The merchants demurred and asked for the matter to be placed before the parties in Mexico City and said that they would abide by the decision whatever that might be. This was refused so after some parlay F. Macmanus and Sons gave Trias $2,000 (and the duties which were about $3,000) and H. Nordwald gave him $4, 000 (and his duties which were nearly $8,000)SD papers, letter H. Nordwald and F. Macmanus and Sons to John W. Foster, 5 March 1877; letter Scott to W. Houston, Secretary to Assistant Secretary of State, Washington, 10 April 1877.

Trias held the city from 2 June until 19 September, when it was again occupied by the opposition.

The two American companies asked for the Díaz’ government to recognise the payment and renew business confidenceSD papers, letter H. Nordwald and F. Macmanus and Sons to John W. Foster, 5 March 877. On 8 March 1877 the U.S. consul, Louis H. Scott, also wrote to Foster, embellishing on the characters of Trias and MuñozSD papers, letter Louis H. Scott to John W. Foster, 8 March 877.Gustavo Moye sent a similar petition through the German Consul to their MinisterSD papers, letter H. Nordwald and F. Macmanus and Sons to John W. Foster, 5 March 877. Trias was “a man entirely “given over to cups.” After his defeat at the “Avalos” on the 19th of Sept. he went to San Antonio Texas, where he carried on his drunken frolics as long as his ill gotten money lasted. He was arrested and fined in the police courts at San Antonio as a common drunkard. When the news of Gen. Diaz’ success became known, Trias returned to Mexico and gathered around him a few of his desperate followers. He and his party came with Gen. Caamaño, and when Gov. Samaniego went out to treat with Gen. Caamaño, a messenger was dispatched to Trias’ camp near by, inviting him to be present at the council. Unfortunately he was too drunk to do so. The following morning when Gen. Caamaño occupied the “Plaza” Trias was so drunk that four men could not place him in his saddle, so the people say who saw him. It was until late in the afternoon of the same day that he could be made presentable.

Now for our worthy Gov. He was refused his seat in the Congress of Mexico as an evil minded man, one who poisoned everything with which he came in contact, and he is generally known here as the “Bird of Prey.” He is of all men that Gen. Diaz could select, the most unpopular, and a more revengeful and vindictive man I know can not be found. He takes affront where none is intended, but it serves his purpose as well and he wrecks his vengeance all the same. Muñoz and Trias would in one short year ruin this state beyond redemption. What can the people of Chihuahua look forward to with a Governor whose chief delight is to bring trouble and disaster upon commerce, who dislikes all foreigners with a deadly hatred, and whose chief ally and supporter is a drunken worthless man who is under the influence of the most desperate class of men the State can produce”.

On 21 March Scott wrote to the State Department, explaining the critical situation of the Americans residing in Chihuahua, and stating that German citizens were protected while Americans were not. Scott asked for instructions on how to act and what protection the treaty between the USA and Mexico gave to Americans residing in MexicoSD papers, letter Scott to State Department, Washington, 21 March 1877.

The day before Naranjo’s arrival in Chihuahua governor Muñoz and General Trias sent an armed force to the offices of H. Nordwald and Francisco Macmanus and Sons demanding from each firm $5,000 or the embargo of their safes. Macmanus and Sons’ duties were a trifle less than $4,000. As they had already paid Caamaño more than the duties amounted to and had given to Trias, with Muñoz’ consent, over $2,000 on the duties they were now exacting for the second time, both replied “take our safes, imprison us, but pay you this amount, we will not, under any consideration whatever.” The troops invaded the private office of Mr. Nordwald and occupied it, but they did not come any further than the door of Macmanus & Sons. Nordwald had also paid Trias a portion of duties before they made a demand on him for the $5,000. The merchants held out, and the next day Naranjo arrived and settled the business by making a new loan to which both merchants paid $2,000 each.

The next day, General Naranjo at the head of fifteen hundred men marched into Chihuahua and remained for thirty days. In order to support his troops he compelled F. Macmanus and Sons to pay him $2,600, for which he gave them an order on the Customs Houses at either Presidio del Norte or El Paso for the amount so paid adding to the order $2,500 which had been paid to General Trias when he occupied Chihuahua during the months of June and July 1876, in return for their receipts. This new order was given by General Naranjo and approved by Governor Muñoz and the chief of the Custom Houses of the state (or State Treasurer). However, later, the Custom House official at Presidio del Norte, Juan Muñoz (a brother of the former governor) informed Macmanus’ agent at Presidio that he had instructions from Mexico City of Mexico not to pass any goods upon the orders of Naranjo. Although he passed goods for Mexican on just such an order, he told Macmanus that he would exact the greater part of any duties in money and accept the orders only for the smaller part. Macmanus and Sons asked for the American Minister in Mexico City o get the orders recognizedSD papers, letter Louis H. Scott to F. H. Seward, Assistant Secretary of State, 9 July 1877.

Naranjo then astounded Macmanus and Sons by saying that he would not recognize the amount paid to Trias on the duties as he did not know what Trias had done with the money. However, he did not succeed however in making them pay more than $540 for the third timeSD papers, letter Louis H. Scott to F. H. Seward, Assistant Secretary of State, 9 July 1877.

Francisco Macmanus once refused payment of a so-called loan of $4,000.Twenty soldiers with fixed bayonets were placed in his store and an officer with drawn sword demanded the money or the result would be worse with him. Macmanus had a notary at his counter and submitted a written protest, but that did not save him from paying the money. He sent the claim to Mexico City but his attorney advised him not to spend any more money over the matter as it was utterly hopeless and he would never recover a cent.

On 4 April Foster met Sr. Vallarte, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, to remonstrate against the exaction of the forced loans. Vallarta sent orders to Chihuahua to desist from forced loans against Americans, and since then American citizens had not been molested. Francisco Macmanus had stated that he with other merchants were requested by Governor Muñoz and General Trias to make some “advance” to them “to pay off their troops, but all these sums had been repaid or adjusted by orders of the Customhouses, which the merchants have accepted; and that the only unsettled claims of American citizens were the loans to Caamaño.

As for the Müller affair, Foster reported to the American Secretary of State that, following the reports in American newspapers, as soon as he had any authentic facts, he brought the matter to the Mexican government’s attention, but of course this was long after Müller had paid the money and been released. Müller had never made a statement of his complaint to Foster or to the consul at Chihuahua, so Foster had no data upon which to make a formal complaint or demand; but he had notified the Minister of Foreign Affairs that in due course he would present a formal complaint and expect full reparation for all damages and injuries to Mr. Müller. The explanation of the release of Mr. Müller’s German companions, at the time of his seizure, as given to Foster, was that the Trias partisans had two causes of ill-will towards Müller personally: firstly, had refused and evaded the payment of a $3,500 forced loan levied by Trias in Chihuahua some months before and secondly, he had participated in the defence of his hacienda, when attacked by a party of Trias guerrillas when a number of the latter had lost their lives. The question of nationality did not enter into the matter so much as the spirit of revenge.

Foster also suggested that it was an opportune time to insist upon the addition of an article to the Treaty of 1831, specifically exempting American residents and property from forced loans{SD papers, letter Foster to William H. Seward, Secretary of State, 26 May 1877.

When Terrazas recaptured the capital his party also resorted to forced loans to pay for the costs of the war since we have a record of a receipt (Billete númo 56) for $1,000 issued to José Dolores Solís. This short-term loan (prestamo de pronto reintegro), which had yet to be repaid three years later, was to cover the expenses of the Jefatura de Hacienda and could be used to pay federal taxes (para cubrir las atenciones de ésta Gefatura de Hacienda ... los cuales ... serán devueltos con los derechos federales que cause próximamente, admitiéndosele en págo de los mismos)details from Clyde Hubbard.

On 12 December 1876 the Porfirista Emiliano Ibarra entered Chinípas and imposed loans on the inhabitants. However, he was attacked four days later by the Comandante Militar Jesús Marquez, Ignacio Rascon and a troop of irregulars and driven back to Sinaloa.

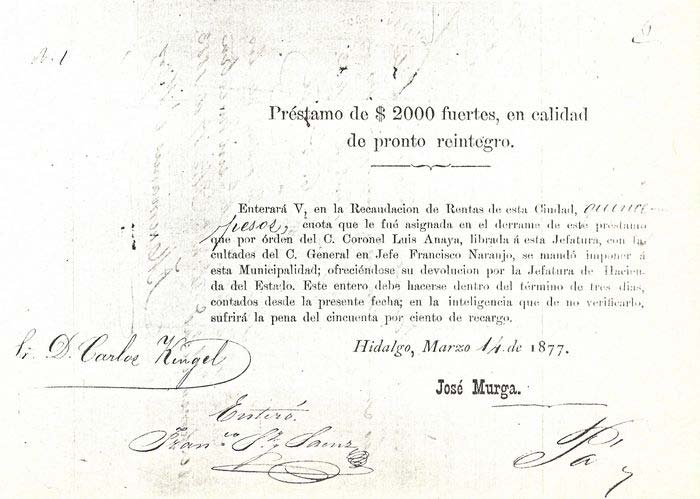

On 18 January 1877 the Porfirista Estanislao González Porras, as Coronel en Jefe de la Brigada de Operaciones and Comandante Militar del Estado, decreed a forced loan of fifteen thousand pesos on the town of Hidalgo del Parral. The loan was to be repaid 'conscientiously and completely' (con toda conciencia y exactitud) as soon as the Porfiristas captured the state capital. Ten days later Porras collected another fifteen thousand pesosAlmada, Resumen de historia del Estado de Chihuahua, Mexico, 1955, has the text of a decree dated 18 January 1877 and of another in similar words dated 28 January 1877. These might refer to the same 15,000 pesos though both demand immediate payment. Almada also has the text of a receipt: 'PRESTAMO FORZOSO. - El Sr. Dn. Luis G. Hevia, ha enterado a la Recaudación de Rentas de esta Ciudad, la cantidad de SEISCIENTOS PESOS FUERTES ($600·00) que le fueron asignados por la Comandancia Militar. - Hidalgo, Enero 28 de 1877'.

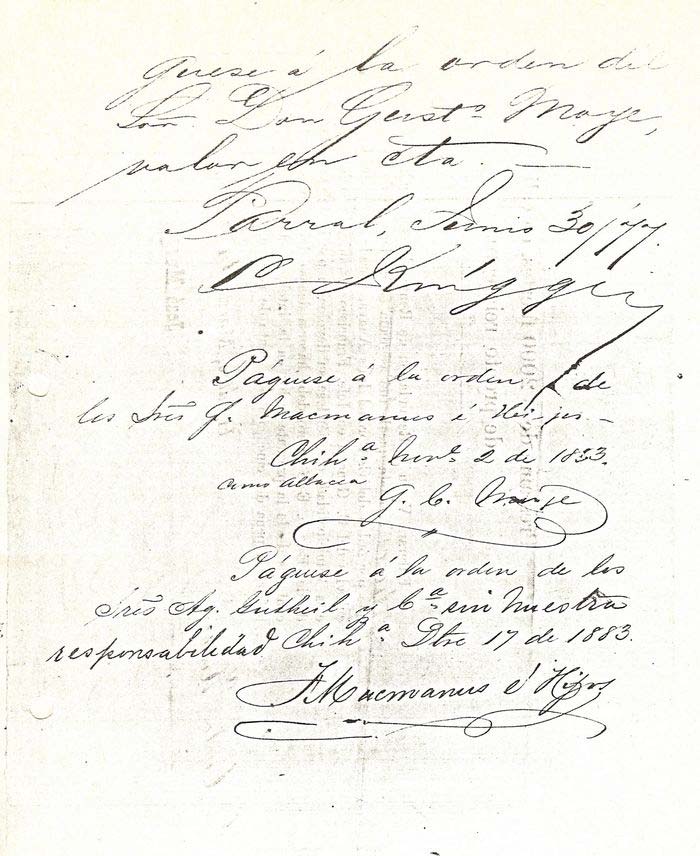

Later Colonel Luis Anaya, using powers granted by General en Jefe Francisco Naranjo, levied another forced loan of $2,000 (Prestamo de $ 2000 fuertes, en calidad de pronto reintegro) on Parral. We know of one receipt for fifteen pesos dated 14 March and signed by José Murga. This was endorsed on three separate occasions, passing at one stage through the hand of Francisco Macmanus y Hijos (the Banco de Santa Eulalia)It was transferred to Gustavo Moye on 30 June 1877; to MacManus and Sons on 2 June 1883 and to Ag. Gulhul y Ca. on 17 September 1883 (details from Clyde Hubbard).

In April 1877 Naranjo negotiated a loan of $10,000 at 12% interest with some of the main businessmen in Ciudad Chihuahua. He should have obtained the authorization of the Federal government because payment was guaranteed with the contributions that the Chihuahua mint would payAP papers, Box 3:1 “Historia Numismatica de Chihuahua”.

On 26 August 1879 there was an uprising in Guerrero, allegedly because of a forced loan (contribución extraordinaria) decreed by the local legislature to pay for the war against the ApachesAlmada, Gobernadores de Chihuahua, 1950, p 369.