El Banco Peninsular Mexicano

Fusion of the two Yucatán banks

During a boom at the beginning of the century both the Yucatán banks, irresponsibly and corruptly, extended credit to henequen growers. These growing abuses were detailed in both the local and Mexico City pressfor example, El Imparcial, Núm. 3905, 20 June 1907, but not before many henequeneros found themselves teetering on the brink of financial ruin. The easy money made available by banks was linked both to local casas exportadoras and foreign lenders. The Banco Yucateco, for instance, was firmly under the control of the Molina house, while the Banco Mercantil was tied to Eusebio Escalante e Hijo and this was of crucial significance, since a weakness in a major casa exportadora could undermine the fiscal well-being of the whole regional banking industry. Foreign lending institutions like the Credit Lyonnais were also vulnerable because of their indulgent investments in peninsular banks. As late as May 1906, French banks had lent three million pesos to the Banco Yucateco, an unwarranted show of confidence in a monocultural economy that was about to come apart.

Frequent speculations by henequeneros in peninsular joint stock companies (sociedades anonimas) further destabilized the regional economy. As the price of henequen continued to decline from 1904 to 1907, the artificially high prices of peninsular stocks could not be maintained. The bubble burst in 1907 and the first local casualty was the Escalante house.

Rumours of the collapse of Eusebio Escalante é Hijo had been circulating in Merida throughout the first months of 1907. The Escalante house was the oldest casa exportadora in Yucatan, and although it could no longer lay claim to dominance in henequen sales, its investments in the Yucatecan economy were still considerable. Besides the commercial house in Merida, the firm owned the Agencia Comercial, whose warehouses, docks, lighters, and other means of transport enabled the Escalantes to move fibre from hacienda to steamship. The Agencia, which had been created in the late 1880s in a partnership with another prominent casa, Manuel Donde y Cia (which succumbed to bankruptcy in an earlier bust cycle in 1895), owned considerable real estate in the port of Progreso. In addition, Escalante e Hijo had invested heavily in the Ferrocarriles Unidos, tramway companies, banks, urban properties and haciendas, a variety of attendant service industries and some chancy agricultural companies in the eastern portion of the peninsula. Like all casas, Escalante é Hijo served as creditor to a great number of hacendados: in some cases, it made cash advances; in others, it provided mortgages to planters. Finally, many wealthy businessmen and individuals in Merida and elsewhere had invested in the Escalante casa.

In a desperate but futile effort to avoid bankruptcy, Nicolas Escalante Peón went to Mexico City in May and June of 1907 to speak with Olegario Molina, Secretario de Fomento, Colonización y Industria, and Limantour, Secretario de Hacienda. What was at stake was more than just the failure of one of the largest henequen firms in the peninsula as the Yucatecan banks, especially the Banco Mercantil (the Escalante bank), were also in imminent danger of default. Limantour agreed to bail out the Yucatecan banks by authorizing the Banco Nacional de México to loan a million pesos to the Banco Yucateco and the Banco Mercantil under certain unspecified conditions. Later in 1908, Limantour agreed to the fusion of the two weakened banks into one stronger institution, the Banco Peninsular Mexicano.

While the federal government had intervened to prop up the peninsular banking industry, it did not, however, rescue the ailing Escalante casa. As a direct result of the Escalante failure in July 1907, Avelino Montes S. en C. would scuttle one of its principal rivals in the henequen trade, obtain control of the Ferrocarriles Unidos de Yucatán and of the peninsular banks, and then use its new clout to purchase a steamship line in 1908. Rarely has a business profited so well from another's misfortune. Escalante's demise ensured Molinista dominance over the key facets of the regional economy.

Although local judges issued a formal order of arrest for both Eusebio Escalante Bates and Nicolas Escalante Peón in 1909, the two were warned by a highly placed 'government functionary' of their impending arrest a full two months before the order was issued. This advance notice gave them enough time to flee to New York. The lawyers for the receivers tracked the Escalantes down in New Rochelle, New York, and through an international legal instrument called 'Letters Rogatory' made the Escalantes take the stand in New York. Despite the numerous legal and ethical questions raised during the trial, however, the Escalantes received a juicio de amparo, or protection, from the Mexican courts and were ultimately exonerated from any criminal wrongdoingJoseph, Gilbert M., and Allen Wells. “Summer of Discontent: Economic Rivalry among Elite Factions during the Late Porfiriato in Yucatan.” Journal of Latin American Studies, vol. 18, no. 2, 1986, pp. 255–282.

As if the banks did not have enough problems, in January 1908 when Antonio Cáceres replaced Mateus Ponce as cajero of the Banco Yucateco it was discovered that the latter had defrauded the bank of $740,000, from a strongbox that contained notes from Mexico City that had not yet been put into circulationEl Tiempo, México, 9 January 1908. Although some culprits were arrested and convicted, the untimely robbery undermined the credibility of the already weakened regional banking industry and paved the way for the fusion of the two banks. The stolen notes were of the $50 and $100 denominations so the new bank gave holders 35 days until 31 December to hand in any notes for exchangeDiario Oficial, Yucatán, Núm. 3695, 15 December 1909.

On 9 May the wife and father-in-law of the mozo of the Banco Yucateco, Abelardo Canto, were arrested and each was found to have $2,000 in bank notes. This reopened the case of the robbery at a time when the public thought that it had been concluded with only the verdict of justice to comeEl Popular, Año XII, Núm. 4,118, 10 May 1908.

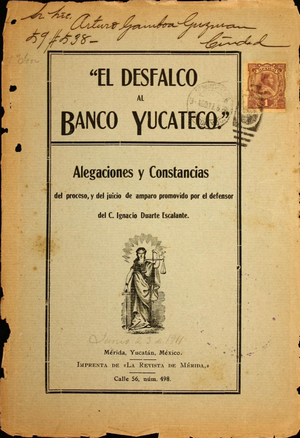

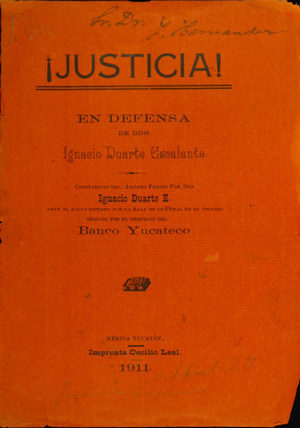

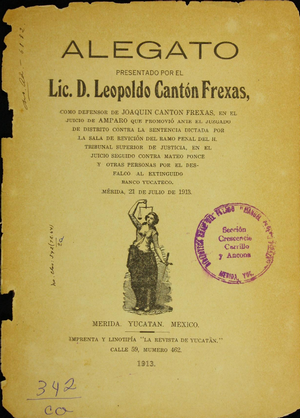

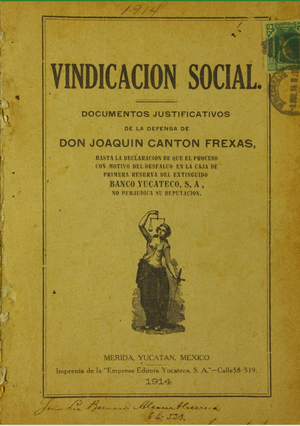

The subsequent trials of Ponce and his supposed associates generated a cottage industry of ligitation and publication over the years.

|

|

|

| El desfalco al Banco Yucateco: alegaciones y constancias del proceso, y del juicio de amparo promovido por el defensor del C. Ignacio Duarte Escalante |

¡Justicia!: en defensa de don Ignacio Duarte Escalante, constancias del amparo pedido por don Ignacio Duarte E. ante el fallo dictado por la sala de lo penal en el proceso seguido por el desfalco del Banco Yucateco |

|

|

|

|

| Alegato presentado por el Lic. D. Leopoldo Cantón Frexas : como defensor de Joaquín Cantón Frexas, en el juicio de amparo que promovió ante el juzgado de distrito contra la sentencia dictada por la sala de revisión del ramo penal del H. Tribunal Superior de Justicia, en el juicio seguido contra Mateo Ponce y otras personas por el desfalco al extinguido Banco Yucateco, Mérida 21 de julio de 1913 | Vindicación Social: documentos justificativos de la defensa de Don Joaquín Cantón Frexas, hasta la declaración de que el proceso con motivo del desfalco en la caja de primera reserva del extinguido Banco Yucateco, S. A., no perjudica su reputación |

The Banco Mercantil de Yucatan shareholders met on 18 January 1908 and agreed to the merger. The shareholders meeting of the Banco Yucateco on 22 January was adjourned until 28 February on account of the discovery of Ponce’s fraudABNC, folder 151, Banco Peninsular Mexicano (1907-1932). The merger was approved by the Secretaría de Hacienda on 11 March 1908 and the new bank started operations on 1 April 1908Memoria de las Institucions de Crédito corresponsiente al año 1908, tomo II. At 30 June the bank had 235,864 notes of the two banks, representing $10,270,006, on hand with another 264,196 notes, worth $5,514,385, in circulation. The interventor was holding another 79,899 notes, worth $2,234, 990ibid..

The board for the new bank was composed of Ricardo Gutiérrez, Alonso Aznar Dondé, Domingo Evia, Eduardo Robleda, Ricardo Molina Hubbe and Enrique Hort, with Agustín Vales Castillo as comisario. The advisory board in Mexico City was Fernando Pimentel y Fagoaga, José A. Signoret and F. de LizardiEl Tiempo, 3 March 1908.

The new bank’s head offices were those of the Banco Yucateco, at calle 58, núm. 510.

On 1 November 1908 Adolfo Leal de los Santos, took over from José Castelló as Director GerenteMemoria de las Instituciones de Crédito correspondiente al año de 1908, vol I..

Notes

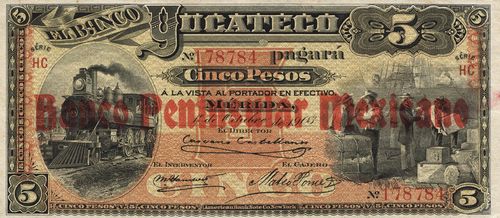

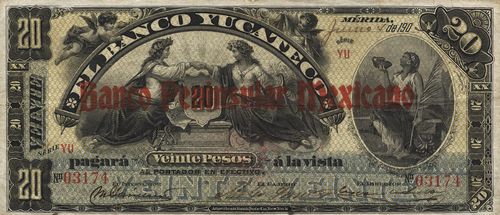

The merged bank used notes of the previous banks, now overprinted in red "Banco Peninsular Mexicano".

M554a $5 Banco Peninsular Mexicano

M554a $5 Banco Peninsular Mexicano

M556a $20 Banco Peninsular Mexicano

M556a $20 Banco Peninsular Mexicano

American Bank Note Company print run

Because of financial constraints the bank did not order any notes from the American Bank Note Company until 1913, though immediately after its formation there was some discussion. One of the bank’s directors, Olegario Molina, offered to get an order for the ABNC in return for a commission. On 15 April 1908 Leslie Hendriks, the company’s Resident Agent in Mexico City, wrote that he had been informed by Hugo Scherer, jr., representing the Banco Nacional de México, the question of stock certificates and bank notes for the new bank would be arranged by the local board in Mexico City and not by the bank in Mérida. Hendriks suggested that if any change be made and an order placed by the bank, it might be well to consider Molina 's offer but as the matter looked then he trusted it would not necessary to do soABNC, folder 151, Banco Peninsular Mexicano (1907-1932).

On 22 May Hendriks reported that he had a letter from Molina, requesting a decision regarding his proposition, and stating that he wished a reply as soon as possible as the National Bank Note Company of Philadelphia had offered him 5% commission if he secured the order for them, but as Molina had approached the ABNC first he felt that it would not be the proper thing to take the matter up with the National until the ABNC had given him a decision. However, Hugo Scherer, jr, had assured him that the orders would be placed by the local board, but not for three or four months to come. “It therefore occurs to me that it would be a good plan to accept Mr. Molina’s offer and pay him 2½%, after our invoice is covered, and not on receipt of the order as he suggests, provided the order is placed by the Bank direct, but not if placed by the Local Board here, or by the Bank through any commission house in New York, as I understand you have previously allowed commissions to such houses and we cannot be expected to pay two commissions. My idea is this: Yucatan business interests form a sort of family affair and they are all out for all the graft possible, and if by any chance, the Bank placed the order, we would be covered. On the other hand, I think it more than likely that the Local Board here being aware of these conditions, will take the ordering out of the hands of the Bank as far as is possible. So that I think will be safe for me to offer Mr. Molina 2½% provided that the Bank itself places the order direct with you, or through this office, but not if the order is placed by the Local Board here, or by the Bank through a New York commission house.” However, Hendriks was talking about orders for stock certificates, not bank notes.

Hendriks was also reassured by Fernando Pimentel y Fagoaga, Vice President and General Manager of the Banco Central Mexicano, the other banks that had rescued the Yucatecan banks, that no order was being placed.

On 9 December 1908 Hendriks heard by accident that the stock certificates had been ordered from Bouligny and Schmidt. He called on Scherer and then on Pimentel who were not only surprised but very much annoyed at this action which they said was absolutely unauthorised and that while it was now too late to do anything about it they would bring the responsible parties to time in the matter. “Mr. Castelló who, until recently was Manager of the Bank, had just returned from Merida and he tells me that the order was placed by the Board in Merida while he was away and that their reason for doing so was that the Societé Marseillaise had telegraphed insisting on immediate delivery of the new shares in exchange for the old ones of the Banco Mercantil and Banco Yucateco which they held. I am extremely mortified to learn of this but I supposed myself safe in relying on Messrs. Scherer and Pimentel and this came with as great a surprise to them as it did to me. In fact, when I went to see them they would neither of them believe me until I proved my statement beyond a doubt. You will notice also that the price is extremely low and we could hardly have been able to do business at this price - $15,500 Gold for 165,000 steel engraved acciones with 50 coupons attached. As far as getting a higher price for better work is concerned, the bank is in no condition to spend any more money than is absolutely necessary. In fact, Mr. Scherer remarked that he did not see how they could afford to order any stock certificates at the present time and that the only reason that they continued to use the old bank notes was because they could not afford to order new ones.”

Hendriks was strongly reprimanded by New York for his failure to secure this order, unjustly in his opinion. He was also pleased to report that the stock certificates produced by. Bouligny & Schmidt Sucrs. for this bank had not turned out satisfactorily.

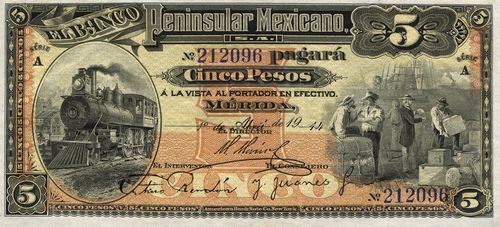

With Huerta’s modification to the Ley General de Instituciones de Crédito the bank, through its agents in New York, Messrs. G. Amsinck & Co., ordered new $1 notes (F 3978). The ABNC found it could alter the dies of the $1 Banco Yucateco and on 21 November 1913 instructed its department to alter the face and back dies by changing the title, changing the date line to read “19---“, changing “CAJERO” to “CONSEJERO”, and erasing the facsimile signatures and engraving new signatures. On 24 November the ABNC submitted the designs and quoted prices and delivery for 500,000 to 1,000,000 notes.

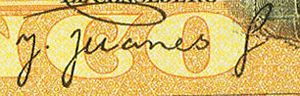

On 8 December 1913 Mr. Focke of Amsinck & Company telephoned to say that he had received a telegram from the bank, stating that they would defer ordering bank notes at present, but the next day they asked to substitute the recent order for $1 notes with an order (F 4011) for 300,00 $5, to be printed from the Banco Yucateco plate with the name changed and the facsimile signatures of M. Marín C. as DIRECTOR and J. Juanes G as CONSEJERO.

M561a $5 Banco Peninsular Mexicano

M561a $5 Banco Peninsular Mexicano

| Date | Value | Number | Series | from | to |

| December 1913 | $5 | 300,000 | A | 1 | 300000 |

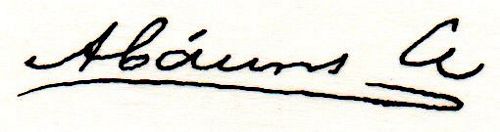

On 20 January 1914 the ABNC returned the unused facsimile (Arturo Rendón as INTERVENTOR) to G. Amsinck & Co.

On 19 February the ABNC forwarded by Wells Fargo Express, per S.S. “Monterey” a box containing 20,000 $5 (A, 000001-020000). On 26 February it sent, per S.S. “Morro Castle”, 100,000 notes (A 20001-120000). On 5 March it sent, per S.S. “Esperanza” another 100,000 (A 120001-220000). Finally it completed the order on 12 March, per S.S. “Mexico” with the remaining 80,000 notes (A 220001-300000).

The plates for the $5 notes were destroyed on 28 August 1931The plates were:

2.–.10 on $5 face plates Nos, A1 & A2

2.–.10 on $5 back plates Nos, A1 & A2

2 – 1 on $5 tints Nos. 1 & 2

made on order F 4011 (ABNC, folder 151, Banco Peninsular Mexicano (1907-1932).

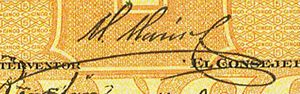

Signatures

The signatures are Menalio Marín Cordoví as Director, Arturo Rendón as Interventor, and José Juanes G. Gutiérrez as Consejero.

Director

|

When Cámara Valdes established the Comisión Reguladora del Mercado del Henequén Marín Cordovíto was appointed to the boardEconomista Mexicano, 18 May 1912. |

|

Interventor

| Arturo Rendón |  |

Consejero

|

José Juanes G. Gutiérrez In 1912 Juanes was president of the Cámara Agrícola de Yucatán and as such, when Cámara Valdes established the Comisión Reguladora del Mercado del Henequén he was appointed to the boardEconomista Mexicano, 18 May 1912. |

|

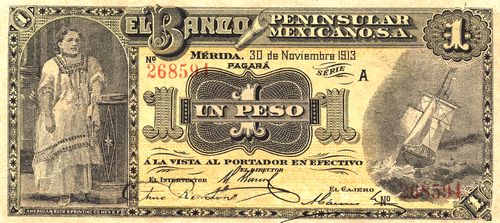

American Book and Printing Company

Though G. Amsinck told the ABNC that the bank had decided agaist a $1 note, it in fact was ordering the same from the Mexico City firm, the American Book and Printing Company. This followed the ABNC's suggestion of a design adapted from the earlier $1 Banco Yucateco note, signed by Rendón as Interventor, Marín as Director and Antonio Cáceres as Cajero.

M560a $1 Banco Peninsular Mexicano

M560a $1 Banco Peninsular Mexicano

Cajero

|

Antonio Cáceres Andrade had been Cajero of the Banco Mercantil de Yucatán since 1 February 1903Períodico Oficial, 6 February 1903. He took over from Matias Ponce as Cajero of the Banco Yucateco on 5 January 1908Periódico Oficial, Año XI, Núm. 3,096, 9 January 1908and was confirmed as Cajero of the new bank from 1 February when the two Yucatán banks mergedEl Diario, vol. VI, núm. 446, 2 January 1908. He was tesorero of the Compañía de Tranvías de Mérida until he resigned in January 1911Periódico Oficial, Año XIV, Núm. 4,039, 25 January 1911. |

|

Under Obregón decree of 31 January 1921 the Banco Peninsular Mexicano was placed into Class B (for banks whose assets and liabilities were about equal and which were given a short time in which to obtain the necessary funds to resume) and allowed to resume all customary operations except the issue of bank notes.