Private issues (bars, restaurants and cafes - others)

As stated in the article in the Mexican Herald in September 1914The Mexican Herald, 20th. Year, No. 6,941, 8 September 1914 saloons issued a large amount of their own vales.

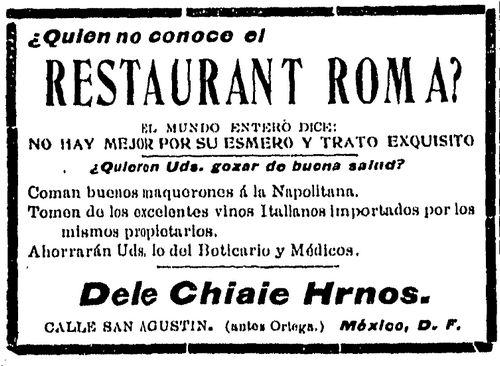

Restaurant “Roma”

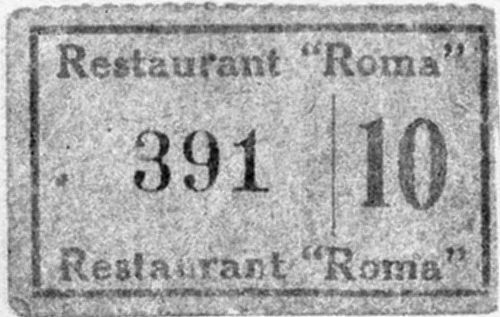

The Restaurant Roma at calle San Agustín was an Italian restaurant run by Pablo delle Chiaie and brothers. We known of a 10c note dated August 1914.

M1423 10c Restaurant Roma

M1423 10c Restaurant Roma

Another set were produced in tear-off strips. These included

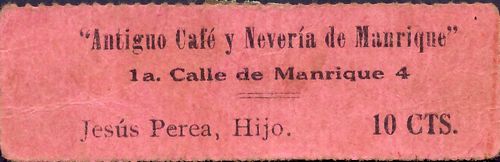

“Antiguo Café y Nevería de Manrique”

M1281 10c Antiguo Café y Nevería de Manrique

M1281 10c Antiguo Café y Nevería de Manrique

A cafe and ice-cream parlour run by Jesús Perea, hijo at 1a. calle de Manrique 4. This cafe, in Tacuba and Monte de Piedad, was certainly antiguo as it was the first café in Mexico, founded, according to a plaque, in 1789. It is said that Miguel Hidalgo plotted there.

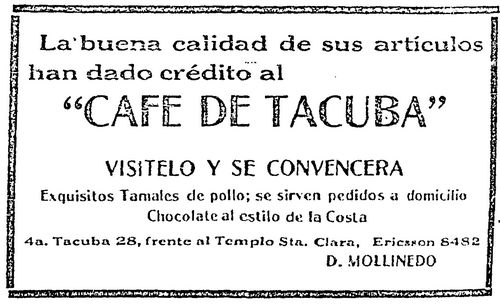

Café de Tacuba

Home delivery of chicken tamales! The Café de Tacuba, housed in a former convent, was opened in 1912 by Dionisio Mollinedo Hernández. It is still operating, run by Dionesio’s great grandson, Juan Pablo Ballesteros, with almost the same décor and dishes.

Home delivery of chicken tamales! The Café de Tacuba, housed in a former convent, was opened in 1912 by Dionisio Mollinedo Hernández. It is still operating, run by Dionesio’s great grandson, Juan Pablo Ballesteros, with almost the same décor and dishes.

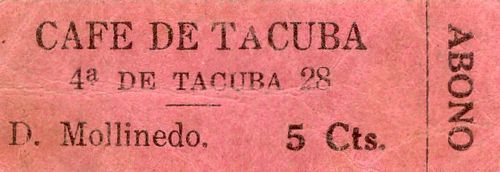

M1297 5c Café de Tacuba

M1297 5c Café de Tacuba

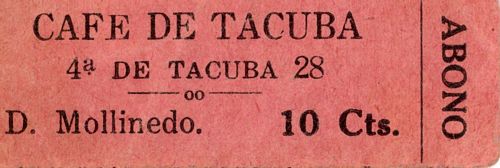

M1298 10c Café de Tacuba

M1298 10c Café de Tacuba

5c and 10c notes were included in Casasola's expositionhttps://mediateca.inah.gob.mx/repositorio/islandora/object/fotografia%3A191512.

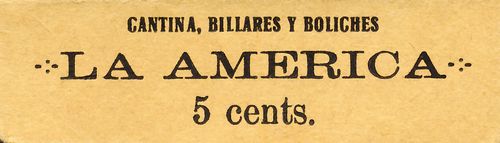

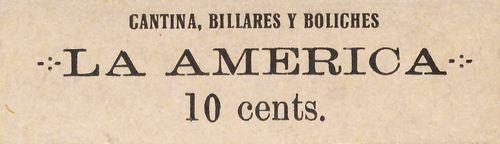

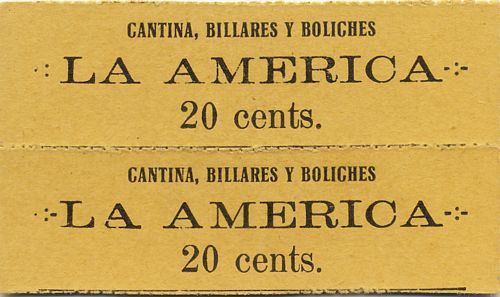

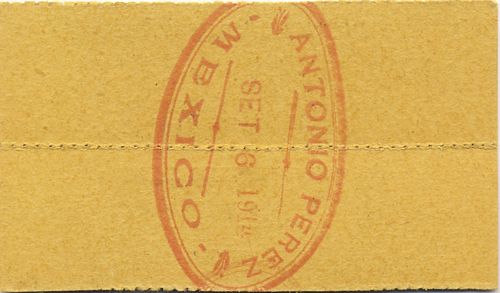

“La America”

M1300a 5c La America

M1300a 5c La America

M1301a 10c La America

M1301a 10c La America

M1302a 20c La America

M1302a 20c La America

A bar, pool hall and bowling alley, at calle 7a de Capuchinas(?), run by the Spaniard, Antonio Pérez. The 20c notes are dated to 6 September 1914.

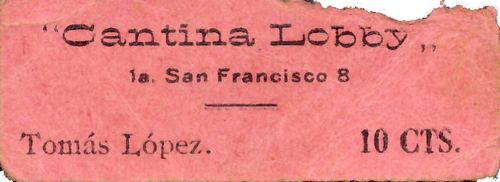

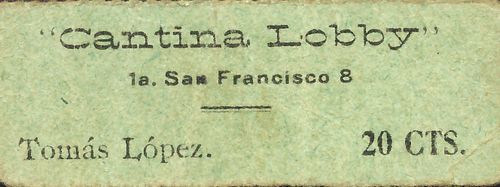

Cantina Lobby

M1308 10c Cantina Lobby

M1308 10c Cantina Lobby

M1309 20c Cantina Lobby

M1309 20c Cantina Lobby

A cantina run by Tomás López at 1a San Francisco 8.

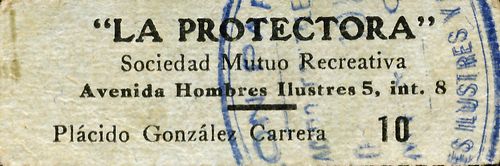

Cantina Salón Paris / "La Protectora"

M1408 10c La Protectora

M1408 10c La Protectora

A 10c note from the Sociedad Mutuo-Recreativa "La Protectora" with the handstamp pf the Sálon Paris, run by Placido González Carrera. The Salón Paris was located at the corner of avenida de los Hombres Ilustres (today avenida Hidalgo) and 1a calle Puente de Mariscala.

Some designs were particular to the establishment, thus

Café de Berna

M1295 50c Café de Berna

M1295 50c Café de Berna

A 50c note. This note was part of a display of vales photographed by Casasola in c. 1915https://mediateca.inah.gob.mx/repositorio/islandora/object/fotografia%3A191512.

Cercle Francais de México

This long-established association had its own restaurant and bar run by J. B. Zerboni.

M1325 20c Cercle Français de México

M1325 20c Cercle Français de México

10c[image needed] and 20c notes, the latter known dated 8 February 1916. The advert on the reverse is for Soberbios cigars from El Buen Tono.

El Alcázar

The restaurant and sweets counter (From Artes y Letras, año V, núm. 119, 4 July 1909)

M1354 20c El Alcázar

M1354 20c El Alcázar

A cafe, restaurant and ice cream parlour at Gante 7, owned by J. Trinidad Guarneros. The stamp on the reverse reads 'TRINIDAD GUARNEROS - ABARROTES NACIONALES Y EXTRANJEROS - OTUM[ ] MEXICO' and is dated 1 September 1915. This particular note was included in Casasola's expositionhttps://mediateca.inah.gob.mx/repositorio/islandora/object/fotografia%3A191511.

Sanborns

In 1898 Walter Sanborn, a young American recently licensed as a pharmacist, took a job in the Mexico City apothecary shop run by an old German named Schmidt. Four years later his brother Frank came down for a visit and was equally fascinated by the country and in 1903 the brothers opened their own drugstore in Mexico City. The business, founded as Farmacía América, became Sanborn Hermanos in 1907.

The Sanborns were not content to run a pharmacy. They started to serve lunch to their employees to keep them from going home for the siesta and soon began serving sandwiches to their customers as well. In 1910 they sent to the United States for a soda fountain, which was still a novelty even there. The needed milk supply for ice cream and malteds was unsafe, but the brothers found a few healthy cows and imported Mexico's first cream separator along with the soda fountain to serve what they claimed was the first scoop of ice cream south of the border. Sanborns did so well catering to the Mexican sweet tooth that the brothers brought in a herd of tested cattle, thereby becoming fathers of Mexico's modern dairy industry. They rented more space to accommodate trade, and the soda fountain grew into a restaurant.

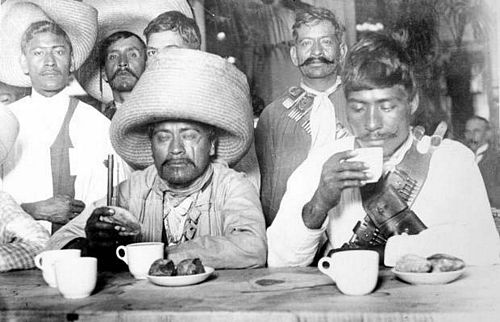

Undoubtedly Sanborns’ most difficult period was the decade that followed the Mexican Revolution of 1910. The store was smashed by soldiers in 1914, when the brothers evacuated their U.S. workers, but it survived as a kind of neutral zone in which Sanborn employees were forbidden to talk politics and the same ban was "tactfully impressed" on its patrons. The troops of Emiliano Zapata used Sanborns as a gathering place, a fact that gave rise to some iconic photographsIconic indeed, and worthy of interpretation. “In December 1914, during the occupation of Mexico City by the División del Norte, and the Zapatista Liberation Army of the South, a group of Zapatistas decided to eat at Sanborns. Their decision to go there was surely not accidental. They knew that Sanborns was where the most powerful people in Mexico shopped and ate. An unknown photographer documented the movement of the troops in the capital and accompanied the Zapatistas into Sanborns. The presence of the Zapatista soldiers in Sanborns signaled that a new political power had arrived in the capital city. Scholars and journalists have often erroneously attributed the setting of these images as within the Casa de los Azulejos. In fact, Sanborns had not yet moved into what would become their flagship location. This common misunderstanding is important to note because Sanborns held social significance long before their store occupied the historic building. The Zapatistas were eating in one of the two Sanborn drugstores found in downtown Mexico City, the one at 12 San Francisco Street and Betlemitas (now Filomeno Mata).

The photographer took several shots of the Zapatistas in Sanborns. One image that is now known as “Sanborns waitresses attend the Zapatistas,” depicts a group of soldiers eating their breakfast at the soda-fountain bar of the drugstore. The major contrasts in the photograph make this particular image very powerful, showing the revolutionary soldiers within an elegant salon of the Porfirian regime. The duality of the situation invites the spectator to glance into the changing political culture of Mexico during the violent period of the Revolution. The image shows a group of rugged Zapatistas wearing bandoliers and sombreros resting their rifles along the lunch counter while drinking coffee and eating bread served by the Sanborns waitresses.

The female workers are shown positioned behind the bar in black dresses, black shirtwaist, and white aprons. One waitress in the center of the photograph posed with her arms extended holding a coffee cup had her eyes fixed ahead towards the soldier who is looking at the camera. The Zapatistas were dining inside the new Sanborns refreshment parlor, the recently inaugurated part of the store devoted to the company’s expanding ice cream and soda fountain business. The soldiers sat around the marble lunch counter in a large room painted white and lined with gold framed mirrors.

These photographs never appeared in illustrated magazines or newspapers at the time. However, they nevertheless came to represent powerful visual testaments of the temporary upheaval of Mexico’s social order during the Mexican Revolution.

Scholars who have analyzed these photographs tend to focus on race and class. Carlos Monsiváis, in his description of the photograph, suggested that, “primitivism peek[ed] into an important site of Porfirian power in order to permit careful comparisons with the elegant ‘científicos’ of the fallen regime.” The Zapatistas had entered a “sacred zone in order to commit profanity, and then, disappear[ed] without a trace

Fernando Benitez said the Zapatistas, “clutched their cups of coffee awkwardly while the waitresses contemplated the great savages as submissive and as frightened as themselves.

The Spanish writer and journalist Arturo Pérez-Reverte described the group of, “serious looking mustached guerrillas so burned by the sun that their skin looks black.”

Andrea Noble noted, “The lack of élan for the city is clearly legible in the faces of these Zapatista troops, whose rural demeanor is wholly incongruous in the gentrified ambience of the North-American ‘soda fountain.”

The significance of the racial descriptions used in these analyses are the binaries that separate a sense of place and entitlement. Sanborns represented the natural site of distinction for elite white Mexicans while the uncouth, rustic, and racially dark colored Zapatistas seemed unsuitable in their urban surroundings. The Zapatistas entered Sanborns because they understood the store’s social meaning and they recognized it as a place reserved for powerful Mexicans. Eating in there served as a symbolic act of resistance against the old Porfirian regime. To borrow from Michel de Certeau, since the Zapatistas lacked their own space in Mexico City, they had to “get along in a network of already established forces and representations.”

What made aristocratic institutions like Sanborns unwelcoming for rural peasant outsiders had much to do with the racial politics and class tensions of the time. During the Porfiriato, indigenous people suffered widespread discrimination due to their ethnicity and were caricaturized in the press as being incompatible with modernity. Sanborns, on the other hand, held particular racial and class connotations connected with Porfirian power and upper-class respectability. Mexicans living in and around the capital understood that Sanborns represented a place of leisure for Mexico City’s upper-class. In choosing to eat there, the Zapatistas deliberately challenged the social meaning of the institution and its associations with Porfirian power and U.S.-styled modern consumerism. They had used the store as a stage to publicly contest state power. The image of the Zapatistas in Sanborns photographs are similar to other acts of political iconoclasm.

On 16 March 1999, eight members from the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) entered Sanborns at the House of Tiles. Wearing their black ski-masks, the group walked towards the back of the store and symbolically recreated the famous scene from eighty-five years before, when the Zapatistas Army from the South had entered the capital and ate along the bar at a Sanborns. The newspaper Reforma reported that Subcommandante Marcos, along with his group of male and female delegates had traveled from La Realidad in the jungles of Chiapas to Mexico City, “to promote the national consultation for the Recognition of the Rights of Indigenous People and for the End of the War of Extermination” in Chiapas. Groups of photographers and television cameras gathered to witness the historic event, as members from the Democratic Revolution Party (PRD) met and ate alongside the Zapatistas. Sanborns waitresses, cooks, and cleaners could not help but greet their famous customers. The Reforma article included a photo recreation of the iconic 1914 photograph of the Zapatistas in Sanborns. In a similar framing, the masked Zapatistas are positioned at the bar while a Sanborns waitress extends her arms with a tray holding a beverage. … As the Zapatistas finished their meal, they filed out through the tea salon while customers shouted, “Long live the EZLN!” and, “Zapata lives!” A reporter asked a delegate from the Zapatistas if they knew what happened in Sanborns eight decades ago. “We know history,” he responded.”( Kevin M. Chrisman, Meet me at Sanborns: Labor, Leisure, Gender and Sexuality in Twentieth-Century Mexico, York University, Toronto, Ontario, October, 2018).

supposedly General Feliciano Polanco Araujo and General Teodoro Rodríguez

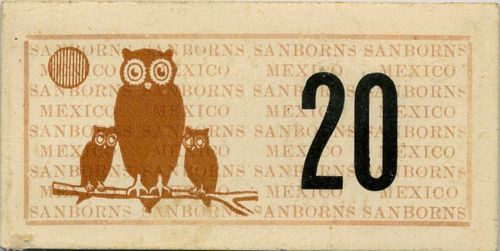

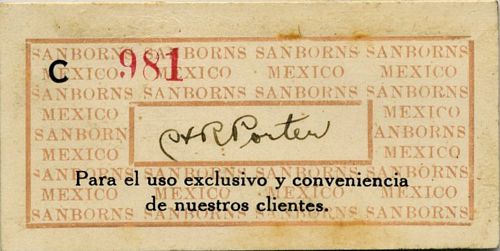

To address the shortage of small change Sanborns produced chits, specifically stated to be “for the exclusive use and convenience of our clients”. 20c and 50c values are known.

M1435 20c Sanborns

M1435 20c Sanborns

M1436 50c Sanborns

M1436 50c Sanborns

| series | from | to | total number |

total value |

||

| 20c | C | includes number 981CNBanxico #10815 | ||||

| 50c |

The signatory is [ ] R. Porter.

| [ ] R. Porter |  |

On 23 June 1915 the Conventionist newspaper El Combate indignantly wrote: 'The cashier at the Sanborn’s drugstore (three calluses on each finger), showing that she is not only ugly but ill educated, refuses to accept the notes that she does not like: yes, the ones that she does not like. And when forced by the outright and convincing arguments of a customer to accept the paper money, she tries at all costs to give in change the shop’s own vales.

Governor, by what right is the famous house of Sanborn’s, which sells cocaine to the effeminate rich (FifisFifi was a characterization as being an upper-class effeminate man. This gendered charge was typical of the time period and the phrase was used to pick on members of the upper-class. Other Mexican newspapers used the term fifí to describe upper-class male customers at Sanborns, e.g. Acción Mundial, 28 April 1916. “La Droguería Sanborns,” “llego otro marchante, mexicano, uno de tantos fifís muy de la casa.” and El Universal, 2 November 1919, “Johnson Fifí!” (ironically, about a fanous African-American refused service because of his colour)) to powder their noses, authorized to issue paper money, or customers obliged to accept those filthy things called vales, which ought to be sent to the Board of Health for disinfection?"El Combate, Tomo I, Núm. 8, 23 June 1915

El Combate returned to the theme on 7 JulyEl Combate, Tomo I, Núm. 20, 7 July 1915, and finally on 27 July the governor of the Federal District banned the use of these vales by shops, hotels, cantinas, restaurants etc under threat of a fine[text needed]El Renovador, Tomo I, Núm. 36, 30 July 1915.

Finally, we need images before we can categorise the following issues.

Cantina Salón Azul

A 5c note[image needed] from this cantina, run by D. Celorio Hermanos.

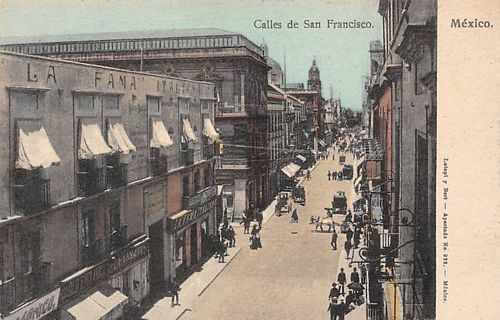

“La Fama Italiana”

A 5c note[image needed] from a gran salón cantina, on the corner of calle de San Francisco and calle de Bolivar, run by Valentín Fernández.

A 5c note[image needed] from a gran salón cantina, on the corner of calle de San Francisco and calle de Bolivar, run by Valentín Fernández.

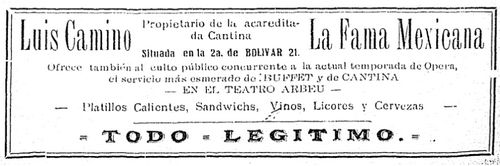

“La Fama Mexicana”

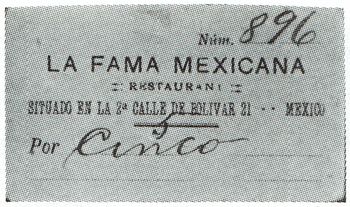

A 5c note], number 896, from a restaurant situated at 2a calle de Bolivar 21 was included in Casasola's expositionhttps://mediateca.inah.gob.mx/repositorio/islandora/object/fotografia%3A191512.

M1400 5c La Fama Mexicana

M1400 5c La Fama Mexicana

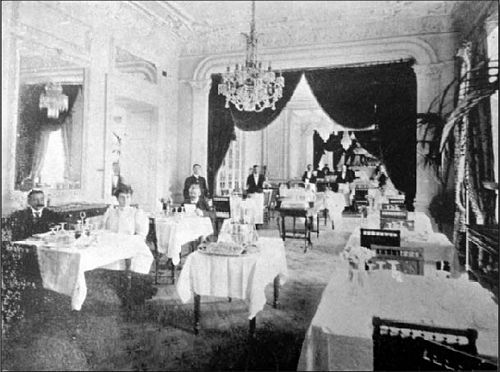

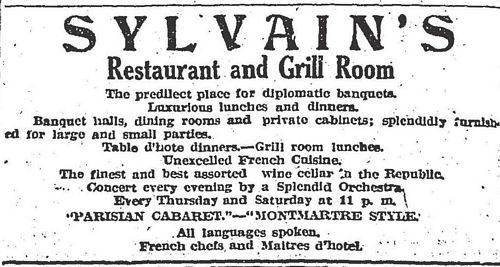

Restaurant Sylvain

Restaurant Sylvain (from Artes y Letras, año II, núm. 23, June 1906)

The Restaurant Sylvain was located at calle de Coliseo (today Bolivar) 36. Its chef, Sylvain Daumont, was President Díaz’ chef for special occasions, and the restaurant was renowned for its cuisine. That it was reduced to issuing vales shows how the shortage of small change affected all levels of society.

We know of a 5c note[image needed].