Manuel Diéguez

On 12 June 1914 Manuel Diéguez, a general in Obregón’s Cuerpo de Ejército del Noroeste, was appointed governor of Jalisco, his native state.

His first two decrees were issued from San Marcos, before Obregón captured the state capital, Guadalajara, on 8 July 1914. Decree núm. 1, on 18 June, made only the Constitutionalist issues of Carranza, Obregón and any issue that Diéguez as state governor was going to make of obligatory acceptance throughout the state. Because of the complete lack of small change, decree núm. 2, on the same date, authorized an issue of $100,000, composed of

| total number |

total value |

|

| 5c | 300,000 | $ 15,000 |

| 10c | 100,000 | 10,000 |

| 20c | 75,000 | 15,000 |

| 50c | 120,000 | 60,000 |

| $100,000 |

These were to be for local use, and would be exchangeable in the Tesorería del Estado for Constitutionalist notes.

San Marcos issue

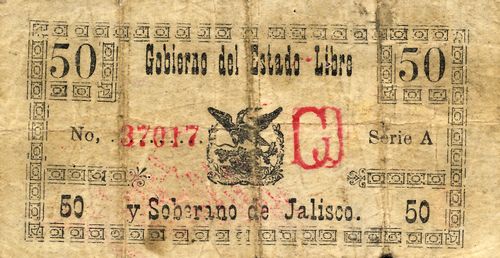

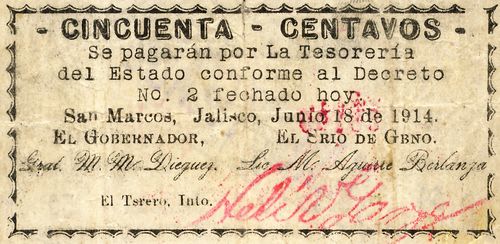

M2342 50c Gobierno del Estado

M2342 50c Gobierno del Estado

| series | from | to | total number |

total value |

||

| 50c | includes numbers 21017CNBanxico #4599 to 38147 |

Diéguez immediately produced some provisional notes whilst still at San Marcos, for simple 50 centavos notes are known. These refer to decree núm. 2 as “today” and have the printed names of Diéguez as governor, Manuel Aguirre Berlanga as secretary, and the hand signature of Helio Garza(?) as interim treasurer.

|

He remained loyal to Carranza, fighting the Villistas in both Jalisco and, later, other states. In 1923 and 1924 he supported Adolfo de la Huerta’s revolution, fighting in Guerrero, Oaxaca and Chiapas, until captured and executed in Tuxtla Gutiérrez on 20 April 1924. |

|

|

He was Secretario General of Jalisco in 1914, governor of Jalisco from April 1915 to April 1916, Carranza’s Subsecretario de Gobernación from 1916 to 1917 and Secretario de Gobernación from 1917 to 1920. He remained loyal to Carranza and retired from public life after Carranza’s murder. He died on 4 October 1953. |

|

| Helio |

These notes found little favour with the public and by late September 1914 the government in Guadalajara was arranging their withdrawal, alongside Obregón’s issue from TepicMéxico Libre, Año I, Tomo I, Núm. 31, 11 September 1914. The exchange took placed in the Jefatura de Hacienda, situated next to the jardín de la Soledad.

First Dirección General de Rentas issue

However, Diéguez later arranged for more professional notes to be printed in Guadalajara, as authorised by his decree núm. 2. This issue consisted of cartones of 5c, 10c and 20c and notes for 50cBoletín Militar, Tomo I, Núm. 15, 1 August 1914. The article also mentions a $1 note. The 20c notes entered circulation on 6 AugustMéxico Libre, Núm. 2, 6 August 1914, and the 5c and 10c were expected shortlyMéxico Libre, Núm. 2, 6 August 1914; El Reformador, 7 August 1914. The 10c cartón was later counterfeited (see below).

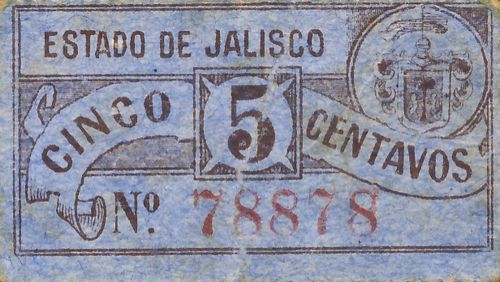

M2309 5c Estado de Jalisco

M2309 5c Estado de Jalisco

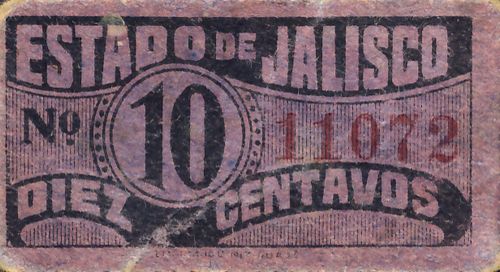

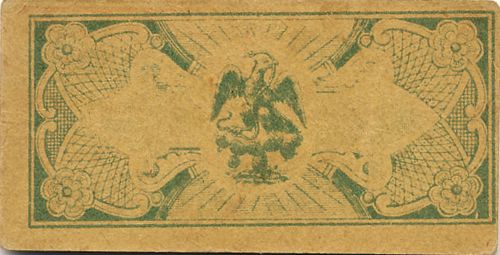

M2310 10c Estado de Jalisco

M2310 10c Estado de Jalisco

M2311 20c Estado de Jalisco

M2311 20c Estado de Jalisco

| from | to | total number |

total value |

||

| 5c | 00001 | includes numbers 00813CNBanxico #11345 to 79243CNBanxico #4506 | |||

| 10c | includes numbers 01538CNBanxico #4510 to 42221CNBanxico #4508 | ||||

| 20c | includes numbers 4342CNBanxico #4513 to 47639CNBanxico #4512 |

According to the printer, José María Iguíniz, he did not have enough pasteboard for the cartones, so the remainder were printed as notes, probably by the Ancira printing house.

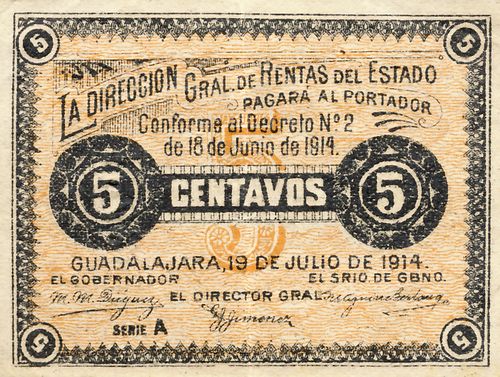

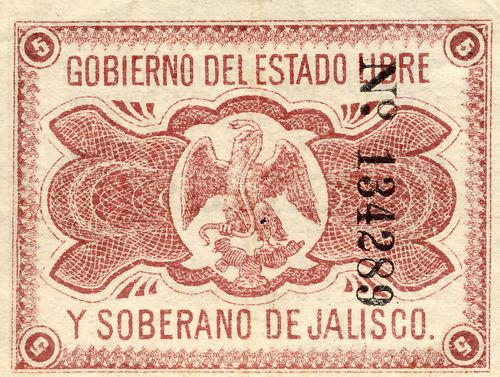

M2313a 5c Gobierno del Estado

M2313a 5c Gobierno del Estado

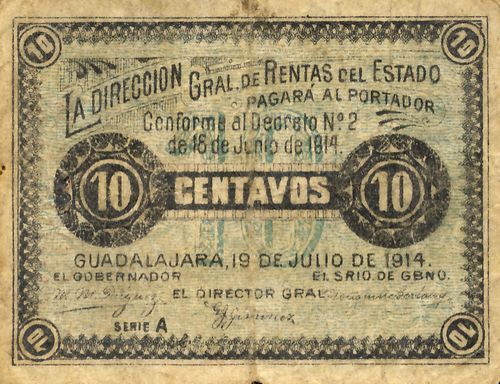

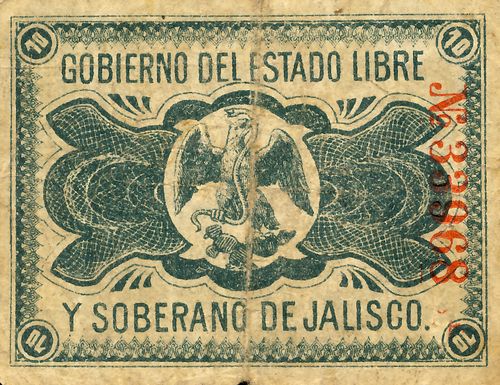

M2314a 10c Gobierno del Estado

M2314a 10c Gobierno del Estado

M2315c 20c Gobierno del Estado 'AMORTIZADO'

M2315c 20c Gobierno del Estado 'AMORTIZADO'

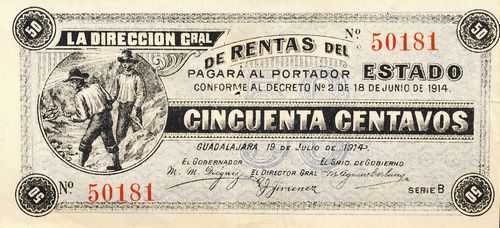

M2316a 50c Gobierno del Estado

M2316a 50c Gobierno del Estado

| date on note | Series | from | to | total number |

total value |

||

| 19 July 1914 | 5c | A | includes numbers 73475CNBanxico #4514 to 289261CNBanxico #4515 | ||||

| 10c | A | includes numbers 33968 to 60456CNBanxico #4516 | |||||

| 20c | A | includes numbers 12906CNBanxico #11350 to 63826 | |||||

| 50c | B | includes numbers 50181 to 90595CNBanxico #4531 |

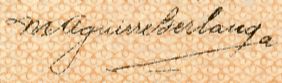

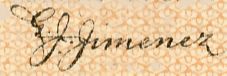

These larger notes carried the printed signatures of Diéguez as governor, Manuel Aguirre Berlanga as secretary, and Gustavo J. Jiménez as Director General de Rentas.

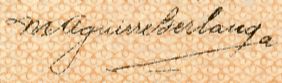

| Manuel Diéguez |  |

| Manuel Aguirre Berlanga |  |

|

Gustavo J. Jiménez was Director General de Rentas in August 1914El Reformador, 7 August 1914. On 21 August it was reported that Adolfo Ruiz, from Hermosillo, Sonora, would take over as Jefe de Hacienda within a few daysEl Reformador, 21 August 1914. Jiménez was Jefe de Hacienda in early September but Ruiz was Jefe by 29 September (Boletín Militar, 30 September 1914). By August 1919 Jiménez had been promoted to be Tesorero General del Estado in OaxacaPeriódico Oficial, Oaxaca, 28 August 1919. |

|

Second Dirección General de Rentas issue

On 11 August, by decree núm 12, Diéguez authorized a further issue of $100,000.

| total number |

total value |

|

| 5c | 100,000 | $ 5,000 |

| 10c | 100,000 | 10,000 |

| 20c | 75,000 | 15,000 |

| 50c | 140,000 | 70,000 |

| $100,000 |

These were supposedly guaranteed by a deposit of Constitutionalist notes in the Dirección General de Rentas and could be exchanged for such Constitutionalist issues, including those issued by the governments of the states of Sonora, Chihuahua, Sinaloa, Durango, Nuevo León and Tamaulipas.

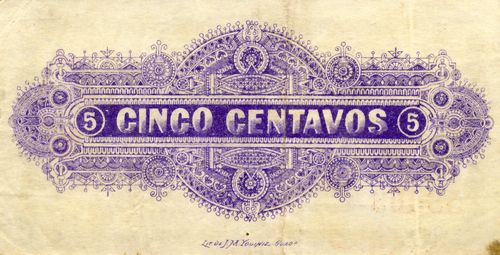

M2318a 5c Dirección Gral de Rentas

M2318a 5c Dirección Gral de Rentas

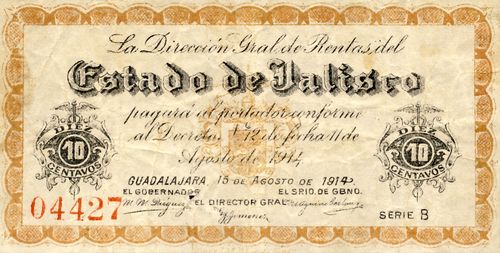

M2319a 10c Dirección Gral de Rentas

M2319a 10c Dirección Gral de Rentas

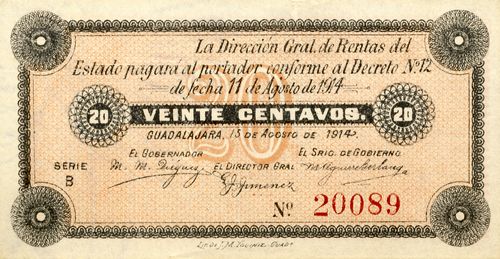

M2320a 20c Dirección Gral de Rentas

M2320a 20c Dirección Gral de Rentas

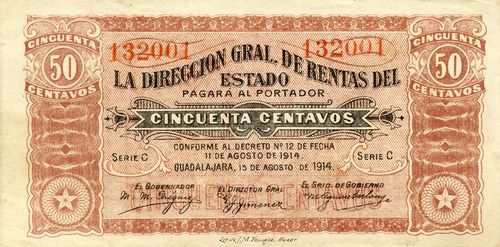

M2321a 50c Dirección Gral de Rentas

M2321a 50c Dirección Gral de Rentas

| date of issue | date on note | Series | from | to | total number |

total value |

||

| 14 September 1914 | 15 August 1914 | 5c | B | 1 | 99999 | 100,000 | 5,000 | includes numbers 45617CNBanxico #4518 to 63841 |

| 10 September 1914 | 10c | B | 1 | 99999 | 100,000 |

10,000 |

includes numbers 04427 to 73893CNBanxico #4524 | |

| 20c | B | 1 | 75000 | 75,000 |

15,000 |

includes number 20046CNBanxico #11357 to 68252CNBanxico #4528 | ||

| 50c | C | 140,000 |

70.000 |

includes numbers 8849CNBanxico #4537 to 80675CNBanxico #11359 |

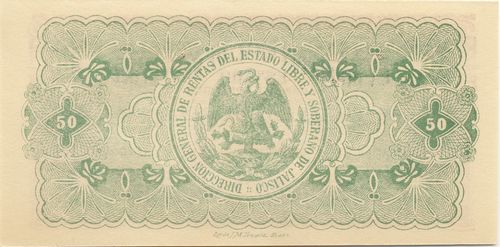

The 50c note was modeled on the Chihuahua 50c note which had been printed in May 1914 by the Maverick-Clarke company of San Antonio, Texas for Francisco Villa’s state government. By August relations between Carranza and Villa were becoming strained, so it is perhaps surprising that they chose this image (and struck with it in subsequent issues). These notes were produced by the well-established local printing house Litografía y Encuadernación de J. M. Iguíniz.

Although the Director de Rentas, Gustavo G. Jiménez, told a newspaper that he expected the new notes to be put into circulation on 24 AugustMéxico Libre, Núm. 8, 19 August 1914 the new 10c notes in fact were put into circulation on 10 SeptemberEl Reformador, Tomo I, Núm. 34, 9 September 1914: México Libre, Núm. 29, 9 September 1914 and the 5c a few days later on 14 SeptemberMéxico Libre, Núm. 35, 15 September 1914. 0n 21 September the Dirección de Rentas received from the printers $20,000 in 50c notes. $50,000 of the $100,000 still needed to be put into circulationEl Reformador, Núm. 44, 22 September 1914. The $20,000 were put into circulation, through exchange, on 22 SeptemberEl Reformador, Núm. 45, 23 September 1914.

Third Dirección General de Rentas issue

On 24 October, by decree núm. 43, Diéguez authorized a third issue of $100,000El Reformador, Tomo I, Núm. 69, 21 October 1914: El Reformador, Tomo I, Núm. 71, 23 October 1914: México Libre, Núm. 73, 23 October 1914, again comprising

| total number |

total value |

|

| 5c | 100,000 | $ 5,000 |

| 10c | 100,000 | 10,000 |

| 20c | 75,000 | 15,000 |

| 50c | 140,000 | 70,000 |

| $100,000 |

.

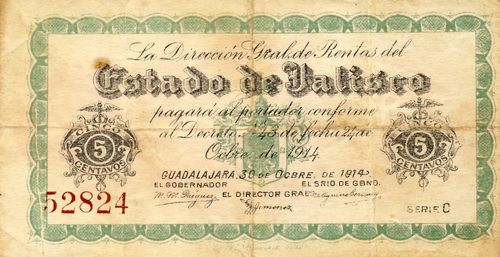

M2323 5c Dirección Gral de Rentas

M2323 5c Dirección Gral de Rentas

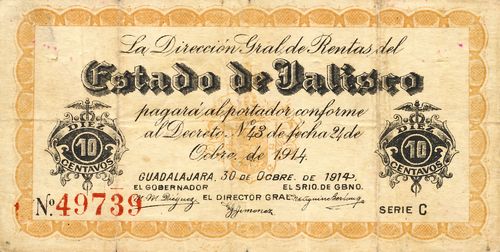

M2324 10c Dirección Gral de Rentas

M2324 10c Dirección Gral de Rentas

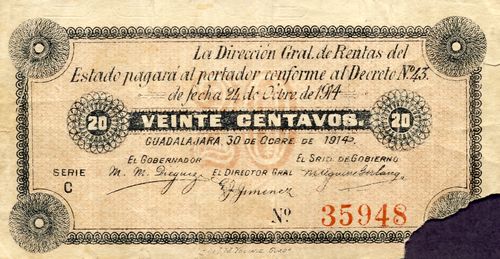

M2325 20c Dirección Gral de Rentas

M2325 20c Dirección Gral de Rentas

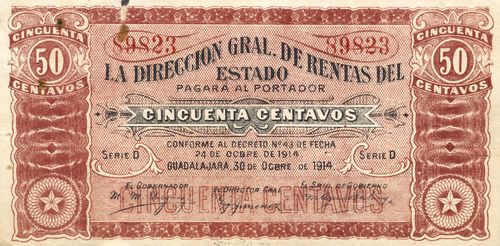

M2326a 50c Dirección Gral de Rentas

M2326a 50c Dirección Gral de Rentas

| date on note | Series | from | to | total number |

total value |

||

| 30 October 1914 | 5c | C | 100,000 | 5,000 | includes numbers 7406CNBanxico #11361 to 27251CNBanxico #4523 | ||

| 10c | C | 100,000 | 10,000 | includes numbers 3663CNBanxico #4525 to 89427 | |||

| 20c | C | 1 | 75000 | 75,000 | 15,000 | includes numbers 34050CNBanxico #11363 to 72577CNBanxico #4529 | |

| 50c | D | 140,000 | 70,000 | includes numbers 81787CNBanxico #4536 to 126767CNBanxico #11364 |

On 11 November Carranza wired Diéguez from Cordoba, Veracruz, saying that should communications be interrupted because of the break with the Convention Diéguez was authorised to issue up to a million pesos in notes to pay for his troopsAHSDN, exp. Xl/481.5/315, ff. 616-617.

Diéguez was not popular with either the upper or the lower classes of society and many of the revolutionaries from Jalisco, headed by Julián C. Medina, joined Villa. On 12 December Diéguez was forced to move his capital to Ciudad Guzmán and two days later was driven out of Guadalajara.

Eugène Cuzin, one of the directors of the Banco de Jalisco, kept a diary of events during part of the revolutionEugène Cuzin, Diario de un francés en México durante la revolución, del 16 de noviembre de 1914 al 9 de julio de 1915, México, Conaculta-Fonca, 2008. Cuzin had to manage and take care of himself, of the companies in his charge (the commercial warehouse La Ciudad de México, the Compañía Industrial de Guadalajara and the Compañía Industrial Manufacturera), of the workers, of the supply of inputs, prices, circulation, devaluation and validity of banknotes, and changing laws; or convince the authorities in turn of the risk that some measures would cause among the population. In November 1914 Diéguez authorised the issue of 2,000,000 pesos (the División del Occidente issue) and in the first week of December Cuzin was concerned about the new issue, assured that the currency would be devalued and asked, "Where will we go?"

Guadalajara's provisional governing board appointed a commission of five people to appear before General Francisco Villa in Ocotlán and inform him that the city had been evacuated, with the aim that the Villista troops arrived in the city as soon as possible and establish a government that would provide guarantees. Among the members of that commission were Manuel Rivas, Holms, the English consul, Julio Collignon, Ernesto Pulsen and Eugène Cuzin. On December 17 Villa and his troops Villa made a triumphant entry, and Medina became governor.

On 8 January 1915 Cuzin noted that the Villista central government had issued 300,000,000 pesos (sic) with the aim of withdrawing from circulation all banknotes and replacing them, with which Cuzin agreed in principle, as they would have "a single type of banknotes instead of all these dirty papers that exist today." Cuzin was upset and worried about the issue of paper money of forced circulation, both Villista and Constitutionalista, and by the devaluation of the peso, which forced them to increase prices. Quite a few counterfeit notes were circulating and it was very difficult to recognize them. The Compañía Industrial Manufacturera accumulated 30,000 pesos in Mexico City without being able to get rid of them, because everybody rejected them and Cuzin mentioned that they would be taken to Guadalajara to be put into circulation. Cuzin had no hope that that would fix matters and noted: "Little by little we are drowning. We have passed more than one sleepless night because of this situation."

On 18 January 1915 Diéguez recaptured Guadalajara from the troops that Villa left behind. With the entry of the Constitutionalists to Guadalajara for the second time, the problems with the circulation of notes were accentuated, for the Villista paper money was rejected by everybody. Cuzin and his businesses accumulated 4,000 pesos in Villista paper and did not know what to do with them. There were poor people who had nothing but those notes and could not buy food. "It could happen that the people will rise up if they arrive to lose all that." Cuzin feared a revolt or a popular mutiny. The Carrancista officials and soldiers also brought worthless notes and were angry if they were not changed in the warehouse, threatening to send the employee to prison. Cuzin heard rumours that they would shoot between 60 and 80 people, so he wrote down the following: "Here's a bit of terror".

On 22 January 1915, pessimism began to take hold of the French merchants gathered at the La Ciudad de Páris warehouse, for the situation was getting worse. The next day, the Director de Rentas published a notice[text needed] stating that all payments made with the Villista money were worthless and had to be paid again before 4 February. Cuzin got very upset saying “We have already paid about eight thousand pesos. But it is very unfair to have to pay again.“

The problems with notes of different denominations and issues was a constant. On 26 January Cuzin faced a conflict. because one of his employees at La Ciudad de México did not want to accept a ten peso note from a Carrancista soldier. The worker was imprisoned and Cuzin, as head of the store was escorted by six soldiers to the barracks of Belén, "like a bandit”. Upon arrival, Cuzin argued with some minor officials, one of them said to him: "All you merchants abuse by rejecting notes. This time we are going to show you who we are." To which Cuzin replied: “I have nothing to do with this place, I do not want to mingle in your affairs. I come only to know why you force me to accept a note that no one accepts, not even your paymasters when they go looking for change.” The official replied: "This note was given to the soldiers, so it is good." Cuzin replied: "Several soldiers and officials have carried counterfeit notes and those that were no longer circulating." He demanded Colonel Ibáñez to tell him what notes they should accept, right away the colonel replied that it was only necessary to read the decrees issued by the Carrancista government. An irritated Cuzin told the soldier: “You are the one who creates all these problems. You give notes to your soldiers and then it turns out that the trade has to accept them in good faith. On this matter there is a decree stipulating that these banknotes are no longer worth anything and it punishes even those who put them into circulation. If they want to be fair, they would talk to the governor and indicate which notes should be accepted. This would avoid problems for all their soldiers, and trade.”

This problem was repeated in other commercial warehouses and they were fined up to 500 pesos. For this reason, the consuls in Guadalajara agreed to protest the way Cuzin was taken away from his establishment, for many thought he would be shot. The issue of notes became more and more complicated, in the morning the government forced them to accept some and in the afternoon they were informed that they were no longer of any value, which made the merchants desperate and they no longer knew what to do.

Fourth Dirección General de Rentas issue

On 4 February, by decree núm. 59, Diéguez authorized a fourth issue of fractional notes - $100,000 comprising of

| total number |

total value |

|

| 5c | 100,000 | $ 5,000 |

| 10c | 50,000 | 50,000 |

| 20c | 50,000 | 10,000 |

| 50c | 160,000 | 80,000 |

| $100,000 |

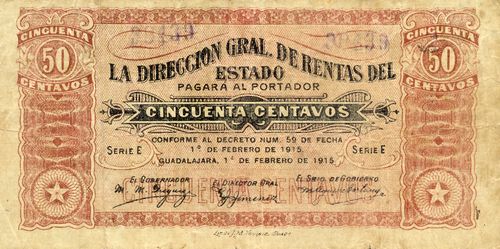

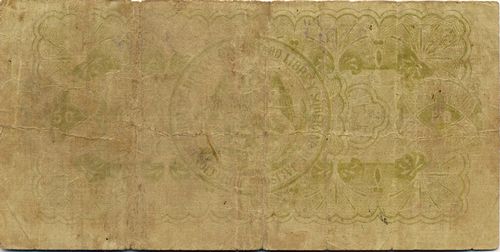

| date on note | Series | from | to | total number |

total value |

||

| 1 February 1915 | 50c | E | 1 | 160000 | 160,000 | 80,000 | includes numbers 39439 to 175798 |

These would be changed, when opportunity offered, for Carranza’s Gobierno Provisional de México notes. However a later decree (núm. 65, see below) referred to 50c notes authorized by a decree of 1 February and this is the date on the only known value. On 6 April 1915, the Villista Medina, in an official clarification, stated that the notes that were of forced circulation in the state were the two Chihuahua issues, the Constitutionalist cartones and the 5c, 10c and 20c notes of the first, second and third issues of the Dirección General de RentasEl Estado de Jalisco, Tomo LXXX, Núm. 42, 8 April 1915; La República, Núm. 59, 9 April 1915. So he was, of necessity, allowing the smaller values but did not acknowledge any 50c notes or Diéguez’ fourth issue.

Villa defeated Diéguez and reoccupied the city on 13 February, being received even more enthusiastically than on the previous occasion but problems continued. On 31 March Cuzin noted that a decree was published declaring null and void all paper money issued by Carranza, which for French businessmen was very delicate because the Compañía Industrial de Guadalajara had accumulated 36,000 pesos of those notes; La Ciudad de París, 6,000 pesos; El Nuevo MundoEl Nuevo Mundo was founded in May 1886 and originally located in the portal Hidalgo, on calle San Francisco Street (today 16 de Septiembre), in front of the Government Palace: then it moved to the building located on the east corner of calle Pedro Moreno and calle Ramón Corona, next to the same palace. The corporate name was Caire y Tiran, the founding partners were Jules Caire and Joseph Tiran (both born in 1862 in the Ubaye valley, Jules Caire in Barcelonnette and Joseph Tiran in Tournoux), and had a share capital of 6 500 pesos, dividing the profits equally. On 15 September 1896, the stock of El Nuevo Mundo became the property of Laurens y Brun, the company formed by Jean Laurens and Auguste Brun, who leased the estate that occupied the business.

In 1909 El Nuevo Mundo was considered one of the finest department stores for clothing and silk. It sold national and foreign goods, made wholesale and retail sales, imported directly from Europe and the United States, and also had a clothing workshop run by French dressmakers (El Regional, Guadalajara, 28 September 1909), 50 000 pesos; La Ciudad de México, 26,000 pesos; the Banco de Jalisco more than 100,000 pesos. Most shops had large sums of that money. So they tried to negotiate with the government to exchange them for more "current" notes.

Julian C. Medina's decree was dated 1 April and stated that all Carrancista currency, including the Ejército Constitucionalista, was invalid, even if it had been restamped in the offices of the Jefatura de HaciendaLa Republica, 1 April 1915. The news that all the currency issued by Carranza was prohibited, irrespective of date or resello, with the exception of the 5c, 10c and 20c cartones, had already been published in Guadalajara on 31 MarchPeriódico Oficial, 8 April 1915. This, therefore, superseded the notice that the Oficina de Timbre had posted up on the same date, in which it informed the public that the Departamento de Hacienda y Fomento in Chihuahua, in a telegram dated 22 March, had said that notes of the Gobierno Provisional issued prior to the split which lacked resellos were of forced circulation until they were exchanged for notes of the Banco de Chihuahua (presumably dos caritas)La Republica, 1 April 1915.

Cuzin was upset by the forced circulation and on 3 April 1915 wrote the following: ”With the forced circulation of banknotes, they can seize everything in exchange for that paper, and then how much will such a paper be worth? Nothing. By this in a way they manage to dispossess everyone, as they intend to do. We will suffer a severe shortage of cereals in four or five months, and the next year the farmers, from whom many oxen have been taken away, will not plant much. Then hunger will come and, perhaps, by force there will be to turn to the United States to supply us with what is missing. And the United States, obviously, will take advantage of the situation to impose conditions.”

On 6 April the Presidente Municipal of Guadalajara, Guilebaldo F Romero, clarified that the notes of forced circulation were the sábanas (which should have a Jefatura de Hacienda del Estado resello), the dos caritas and the Estado de Durango notes signed by F. R. Laurenzana, Pastor Rouaix y M. del Real AlfraroEl Estado de Jalisco, 6 April 1915. However, on the same day, Governor General Julián C. Medina, announced that the only notes of forced circulation were (1) both Chihuahua issues, (2) Constitutionalist cartones of 5c, 10c and 20c, (though not those of Colima or any other state), and (3) the 5c, 10c and 20c notes of the Dirección General de Rentas de Jalisco dated 19 June, 15 August and 24 October 1914El Estado de Jalisco, 8 April 1915.

Diéguez then retook the city on 18 April 1915. On 23 April, with news of Villa’s defeat, the problem worsened, many commercial establishments rejected the one-peso Villista notes which they had been accepting. The poor and the workers had nothing but these. The presidente municipal agreed with the merchants accepting the one-peso notes, but Lieutenant Ulloa proposed that they should all be received regardless of their value, a proposal opposed by Cuzin and eight merchants because it would be very serious for them, because they would accumulate that money in exchange for the goods. However, the public approved of the lieutenant's initiative. Despite this, the presidente municipal agreed with the proposal of Cuzin and the other merchants and decided to put into circulation only one peso Villista notes. Alfred Lèbre, from La Ciudad de Londres, agreed to have all the notes circulated, but Cuzin convinced him that it was "stupid". Lèbre finally agreed.

During these changes in fortune both sides made pronouncements about the paper money in issue, and there are a series of overprints known on the other issues as one side or the other revalidated notes. However, Diéguez’ own issues escaped the need for revalidation, possibly because their quality made them less susceptible to counterfeiting. Thus, on 11 January 1915 Medina told people to present the money issued by Conventionist jefes who had operated in the state at the Dirección General de Rentas before 31 January to check its validity as after that date it would be considered worthlessEl Estado de Jalisco, Tomo LXXX, Núm 14, 12 January 1915. Then on 19 January the newly-arrived Diéguez published Carranza’s decree of 27 November disowning Chihuahua and Convention issues. On the next day, he issued another series of notes ($1, $5 and $10), but in his capacity as General en Jefe de la División de Occidente, rather than as governor.

Berlanga's decree

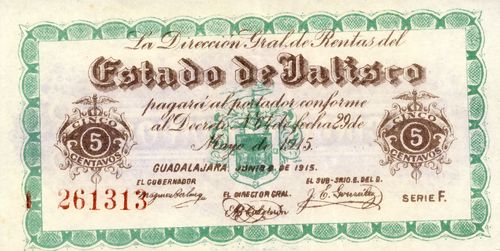

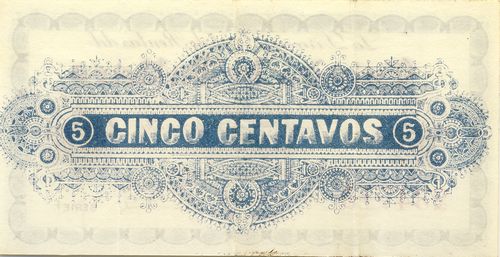

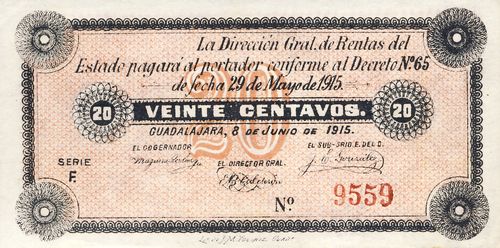

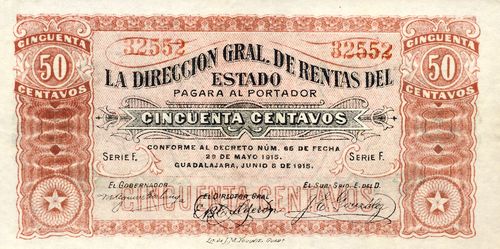

Finally, on 29 May, in decree núm. 65, Manuel Aguirre Berlanga, now interim governor, authorized a fifth issue:

| total number |

total value |

|

| 5c | 200,000 | $10,000 |

| 10c | 100,000 | 10,000 |

| 20c | 100,000 | 20,000 |

| 50c | 140,000 | 50,000 |

| $90,000 |

and also increased by another $10,000 the 50c notes of the 1 February decree.

| number | value | |

| 50c | 20,000 | $10,000 |

| $10,000 |

Some 5c notes refer to 'Decreto No 64' instead of the correct 'Decreto No 65'.

| date on note | Series | from | to | total number |

total value |

||

| 1 February 1915 | 50c | E | 160001 | 180000 | 20,000 | 10,000 | includes number 166291CNBanxico #11365 |

| 8 June 1915 | 5c | F | 200,000 | 10,000 | 'Decreto No 64' includes numbers 12421CNBanxico #4522 and 261350CNBanxico #4521 |

||

| 'Decreto No 65' includes number 115793CNBanxico #4520 and 263977CNBanxico #4519 |

|||||||

| 20c | F | 1 | 99999 | 100,000 | 20,000 | includes numbers 4884 to 91425CNBanxico #4526 | |

| 50c | F | 140,000 | 50,000 | includes numbers 30632 to 79832CNBanxico #4532 |

Counterfeits

On 4 September 1915 the Director General de Rentas, E, B. Calderón, published a warning that counterfeit 10c cartones had been found. Examples of counterfeit and legitimate notes were on display in the department stores “La Ciudad de México” and “La Fama Italiana” so that people could know the differencesBoletín Militar, Tomo III, Núm. 260, 5 September 1915.

Use in other states

Guanajuato

On 12 February 1916 Salvatierra in Guanajuato was told that Diéguez notes were of forced circulationASalvatierra, caja 1915 telegram José Siurob, Guanajuato, to Héctor E. Huacuja, Presidente Municipal, Salvatierra12 February 1916.

Sinaloa

In August 1915 Coronel José J. Obregón in Mazatlán, declared that the latest issue of notes from Jalisco were of forced circulation in SinaloaBoletín Militar, Tomo III, Núm. 235, 7 August 1915.

Zacatecas

On 27 August 1915 the Jefe Pólitico in Zacatecas, L. T. Villaseñor advised that the notes issued by the Pagaduría General del Ejército del Noroeste, as well as those issued by General M. M. Diéguez in Guadalajara and by the Zacatecas Cámara de Comercio were of forced circulation.

Withdrawal

On 11 May 1915 Carranza’s Secretaría de Hacienda, in a list of notes, included in those that were of legal tender, the ones issued by General Diéguez, as governor of Jalisco, in accordance with the Secretaría’s authorization of 27 March 1915.

On 28 June Carranza, in his circular núm. 28, stating that the need for the fractional notes (10c, 20c and 50c) of the Cuerpo de Ejército del Noreste had passed, ordered that they be exchanged in the Tesorería General de la Nación for other Constitutionalist notes. This circular was reprinted in the Boletin Militar of 25 September.

On 29 August Obregón, in Mexico City, wrote to Carranza, in Veracruz, asking to order that the notes issued by Díeguez in Guadalajara could be changed as the public still held them and in some places there were difficulties because they were not considered as of legal and forced circulationABarragán, caja III, exp. 25, f. 52.

On 18 September the Secretaría announced that until it had sufficient funds to exchange the notes issued by Obregón and Diéguez Carranza had decreed that these would continue to be of forced circulation. Two days later the Jefe de Hacienda in Guadalajara, G. Vargas, stated that the notes still remained of legal, forced circulation, until they were exchanged in his JefaturaBoletín Militar, Tomo III, Núm. 277, 26 September 1915. In this respect these notes were in a better position than others that had to be deposited in the Jefaturas in exchange for receipts, to be redeemed at a later date. They appear to have remained a dominant issue in the west of the country for a few more months.

On 28 April 1916, as part of the move to introduce a unified currency, Carranza listed various issues, including the 20 January 1915 issue, that would be accepted until 30 June on deposit by the Tesorería General de la Nación, Jefaturas de Hacienda and Administraciones Principales del Timbre. After that date they would be null and void. All other notes were declared null and void. An American stationed in Guadalajara recorded the effect of this decree on the Diéguez issue: “One of the effects of this edict was to throw out of circulation at once all the Obregón and Diéguez money which, on account of one of the many former financial edicts requiring all other kinds of revolutionary money except the Obregón-Diéguez issues to “resellado” (restamped), had become the favorite money here. This favoritism for the Obregón and Diéguez money was heightened from the fact that such a large percentage of the money which had to be “resellado” was being declared “falso” (counterfeit) by the government agents. Therefore, when the Obregón and Diéguez money was suddenly thrown out of circulation by said edict, many, and especially the market people and wage earners, were caught with hardly any other kind of money in their possession. Moreover, nearly all the subsidiary bills used here for small change were of these issues. Hence thousands of people awoke on Wednesday morning, the 3rd of May, and found themselves unable to purchase in the markets of the city as much as a day’s rations. And there was not offered any relief ahead than the promise by the government that after the 30th of June they might deposit with the government’s agents such money as was yet permitted to circulate and receive – something in the future – one infalsificable pesos for every two of the old." “That there have been abuses on the part of the business public, there can be no question, but to charge them with being the cause of the depreciation in the value of the paper money of the country is absurd. Nearly everything that the present de facto Government has done, has resulted in benefiting the military, to the detriment of the public. A civilian could not get his demonetised bills exchanged at all, unless he used an officer as a "go between," and paid usurious percentages to have it done. This was common knowledge. Hence, about ninety-nine per cent of the civilians lost out on the "deal."Will B. Davis, Experiences and Observations of an American Consular Officer during the recent Mexican Revolutions, 1920, p234. Davis also recorded that the American William B. Arrington, proprietor of a large Notions Store, came to the Consulate and said, "A party wanted me to accept 600 pesos in payment for some mirrors. The money which he offered was such as is being declared counterfeit by the Government's agents. I declined to accept such money. He went away but returned soon after with some agents of the Presidente Municipal, who informed me that if I continued to refuse the money offered me, I would be arrested and fined.” The consul said that officers and soldiers were systematically working off all the notes which they had that had been declared bogus by the government's agents, and were being aided in doing so by the Presidente Municipal.

On 4 April Arrington was arrested by order of the Presidente Municipal, for having refused to accept two counterfeit notes of twenty pesos each, and on refusing to pay the fine of 500 pesos which the Presidente Municipal assessed against him for the offence, Arrington was sent to the Penitentiary. When the consul told Castellanos that he wanted to close Arrington’s business, Castellanos unhesitatingly, and very emphatically said that if the store was closed in the face of General Carranza's edict, that it would be reopened at once, and the goods would be sold as the edict directed should be done in such cases. The consul informed the State Department and went to see Governor Diéguez. The consul told Governor Diéguez that Arrington did not refuse to take Constitutionalista money but was refusing only such money as the Government's own experts were declaring to be counterfeit or such as the Constitutionalistas themselves were refusing to accept as Constitutionalista money. Governor Diéguez pretended not to have heard of the case, and promised to take the matter up with the Presidente Municipal. Arrington was put at liberty by Governor Diéguez on 9 April after an imprisonment of five days without fine or other penalty.

On 10 April Davis reported that there were, counting all nationalities, over five hundred business men arrested and jailed a few days ago by orders of Governor Diéguez, for alleged disregard of the provisions of the Carranza edict, but not one American arrested. It was a curious sight to see the heads of nearly every business house in the city under arrest while the Government's agents were fleecing them of something over two and one-half million pesos.

On 4 May Diéguez wrote to the presidentes municipales that his government had learnt that businesses and the public were refusing his fractional currency but that they should be severely punished, in the concept that once the infalsificables were in circulation, the fractional notes would be quoted, in all cases, at the rate of two pesos for one infalsificableAHLagos, Presidencia Municipal, COR, 1916, caja 156, exp. 4432.

On 12 July Governor Diéguez, in his circular núm. 74, stated that as a result of Carranza’s decree the state’s fractional currency had ceased to circulate but could be exchanged for infalsificables in the Dirección General de Rentas or its office until 30 September, after which it would be null and voidAHTeq, Sección Presidencia, Serié Correspondencia, Año 1915, caja 1, exp. 12. On 24 July Carranza decreed that from 1 August they would exchange the notes listed in the decree of 28 April that had been deposited in the offices of Hacienda with infalsificables at a rate of 10 to 1.