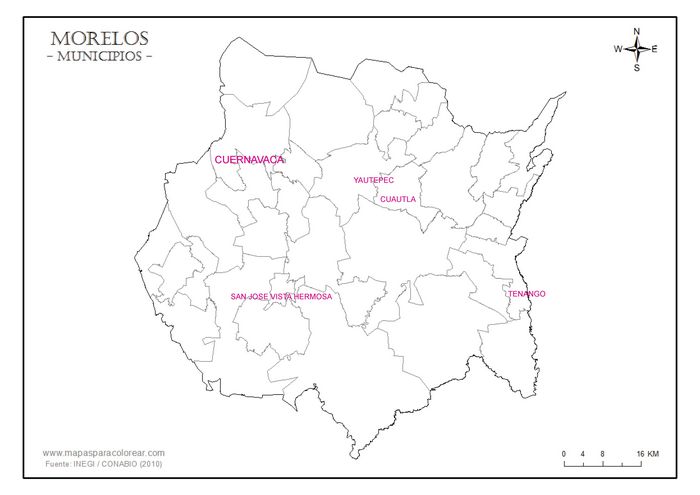

Private issues

Yautepec

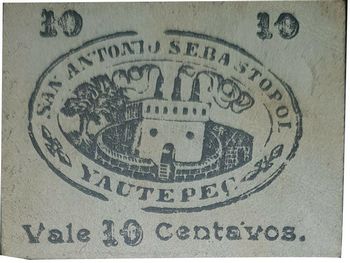

San Antonio Sebastopol

M3235 10c San Antonio Sebastopol

M3235 10c San Antonio Sebastopol

Dick Long, as far back as 1974, was warning that this might be a fantasy. However, if they are legitimate, they come from the Sebastopol sugar mill of Daniel Reyes, one of the most important industries in Yautepec in the first decade of the century. They have a datestamp for MAR 8 1914 on the reverse.

Cuautla

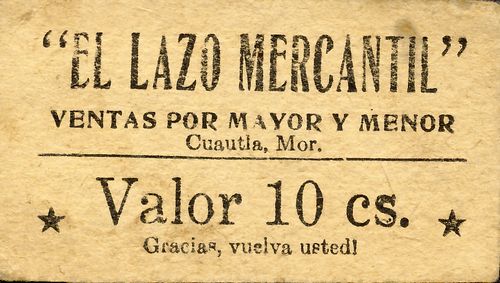

El Lazo Mercantil

M3230 10c El Lazo Mercantil

M3230 10c El Lazo Mercantil

A 10c note from a wholesale/retail store. The legend 'Gracias, vuelva usted (Thanks. Come again)' suggests that it was a coupon rather an a substitute for cash..

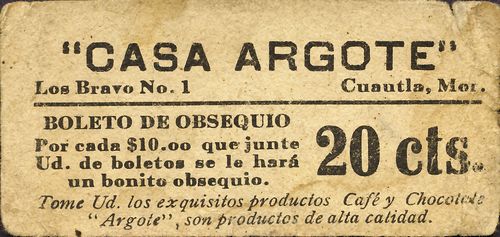

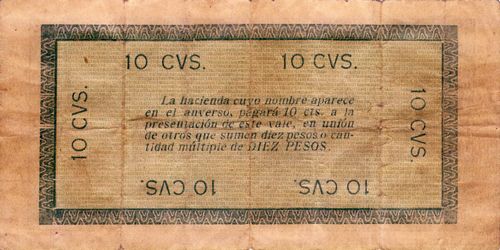

Casa Argote

M3233 20c Casa Argote

M3233 20c Casa Argote

The “Casa Argote” produced coffee and chocolate of, according to this note, high quality. This is described as a gift ticket (boleto de obsequio) and states that for every fifty tickets collected the holder would receive a nice gift (por cada $10.00 que junta Ud. de boletos se le hará un bonito obsequio). However, it might have been used as a substitute for cash.

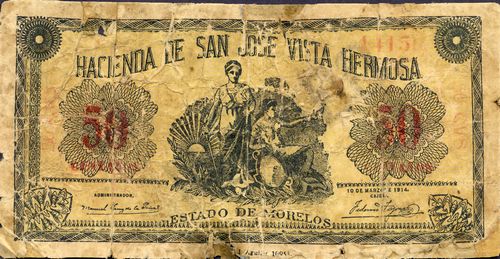

San José Vista Hermosa

Hacienda de San José Vista Hermosa

The Hacienda de San José Vista Hermosa dates all the way back to the conquistador Hernán Cortés. In 1820 it was bought by Manuel Vicente Vidal, whose family owned it until 1910, when they were driven out by General Emiliano Zapata. By the end of the revolution it was in ruins, but was bought and restored in 1945 as a hotel.

M3237a 10c Hacienda de San José Vista Hermosa

M3237a 10c Hacienda de San José Vista Hermosa

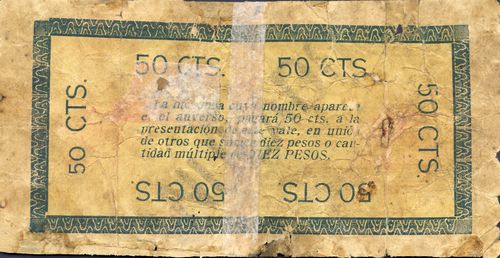

M3239 50c Hacienda de San José Vista Hermosa

M3239 50c Hacienda de San José Vista Hermosa

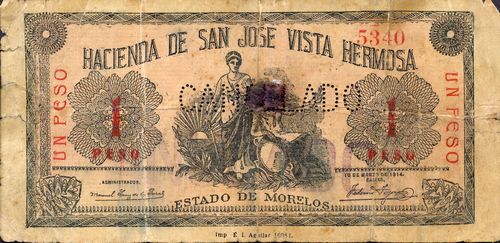

M3240 $1 Hacienda de San José Vista Hermosa

M3240 $1 Hacienda de San José Vista Hermosa

| from | to | total number |

total value |

||

| 5c | |||||

| 10c | |||||

| 50c | includes number 14156 | ||||

| $1 | includes number 5340 |

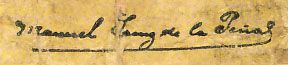

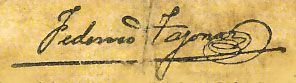

Four values printed by the Mexico City firm of Eduardo I. Aguilar. They are dated 10 March 1914 and carry the printed signatures of Manuel [ ] de la Peñas[identification needed] as Administrator and Feder[ ][identification needed] as Cajero.

| Manuel [ ] de la Peñas |  |

| Feder[ ] |  |

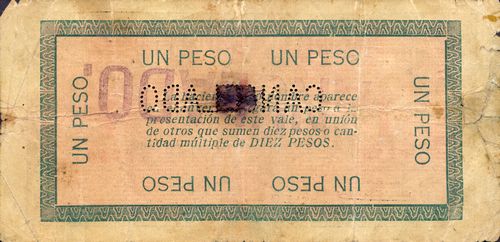

The legend on the reverse states that they were exchangeable for cash in multiples of ten pesos. It also refers to “the hacienda whose name appears on the front” which suggests that Aguilar produced similar notes for other haciendas.

Tenango

Hacienda de Tenango

Santa Ana Tenango, 1905 (courtesy Archivo de Pablo Bernal)

Luis García Pimentel (1855-1930) was an acknowledged representative of the Porfirian regional elite of Morelos and the owner of two sugar haciendas located in the east of the state, Santa Ana Tenango and Santa Clara Montefalco. Luís took over the reins of the family business when his father, Joaquín García Icazbalceta died, modernizing the machinery, building a 57 kilometre canal to bring irrigation water from Cuautla, introducing tracks for the platforms that took the cane from the field to the mill and sugar to the railway station. He installed a dynamo that provided electricity to his mills, grinding the cane with electric machines and illuminating the main buildings of the haciendas with electric light before this service existed in Mexico City.

The García Pimentel family owned the mill at the beginning of the Mexican Revolution. On 3 April 1911 the hacienda was attacked by a group commanded by Emiliano Zapata which burned the sugar cane fields and some of the houses of the employees and dynamited the tienda de raya. The García Pimentel managed to continue sugar production, thanks to the payment of an insurance policy from Lloyd's of London for £14,000. They defended their heritage as much as they could, to the point of organizing a battalion of Japanese "Samurai". Unfortunately, in 1914, the factory and the main house were attacked by revolutionaries and destroyed by fire and dynamite. It is said that the hacienda burned for eight days. The remains of the magnificent construction were completely abandoned and all economic activity ceased completely.

We know of handwritten vales from early 1914.

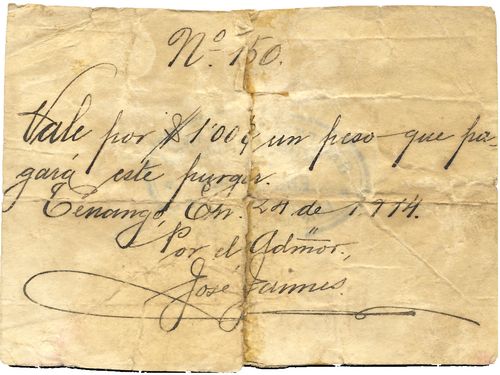

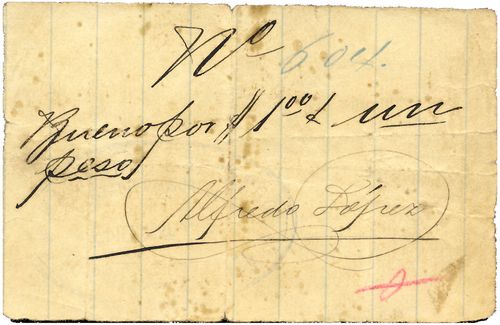

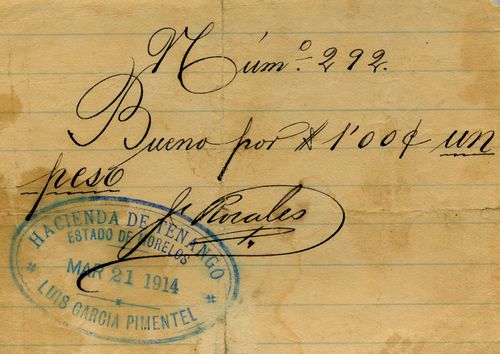

M3242a $1 Hacienda de Tenango

M3242a $1 Hacienda de Tenango

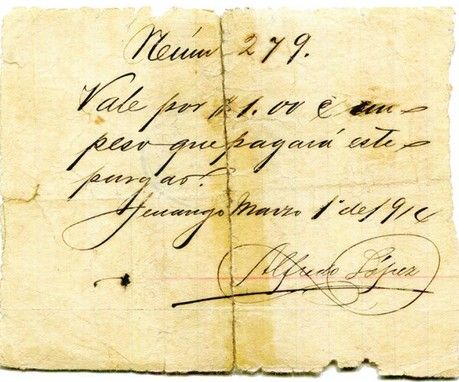

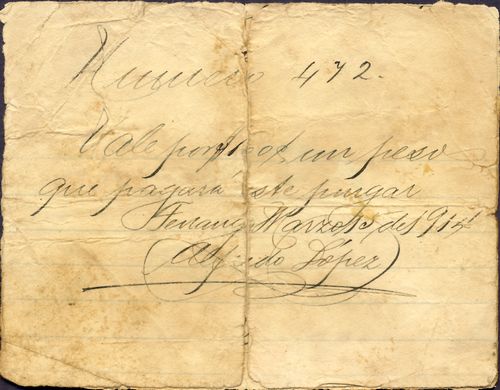

M3242b $1 Hacienda de Tenango

M3242b $1 Hacienda de Tenango

M3242b $1 Hacienda de Tenango

M3242b $1 Hacienda de Tenango

M3244 $1 Hacienda de Tenango

M3244 $1 Hacienda de Tenango

M3243 $1 Hacienda de Tenango

M3243 $1 Hacienda de Tenango

| date on note | from | to | total number |

total value |

signed by | ||

| $1 | 20 January 1914 | José Jaimes | includes number 6 | ||||

| 24 January 1914 | includes numbers 64CNBanxico #5418 to 169CNBanxico #11672 | ||||||

| 1 March 1914 | Alfredo López | includes number 279 | |||||

| 14 March 1914 | includes number 493 | ||||||

| 15 March 1914 | includes numbers 424CNBanxico #5420 to 492CNBanxico #5419 | ||||||

| 21 March 1914 | J. Rosales | includes numbers 237 to 292CNBanxico #11674 |

The signatories were

| José Jaimes signed for the Administrador |  |

| Alfredo López |  |

| J. Rosales |  |

Before the revolution, García Pimentel had been a prosperous businessmen, who was familiar with his surroundings, which he leveraged to increase his profits. After the armed struggle however, he was unable to recover his previous economic successMaría Carolina Moguel Pasquel, “Un empresario agrícola porfirista en Morelos. El caso de Luis García Pimentel” in Secuencia, 97, January-April 2017, pp. 170-199.