Lumija plantation and other plantations

The La Zacualpa-Hidalgo Rubber Corporation

Water Carriers at the Fountain – La Zacualpa Rubber Plantation

(from John W. Butler, Rubber, What it is and How it grows, 1908)

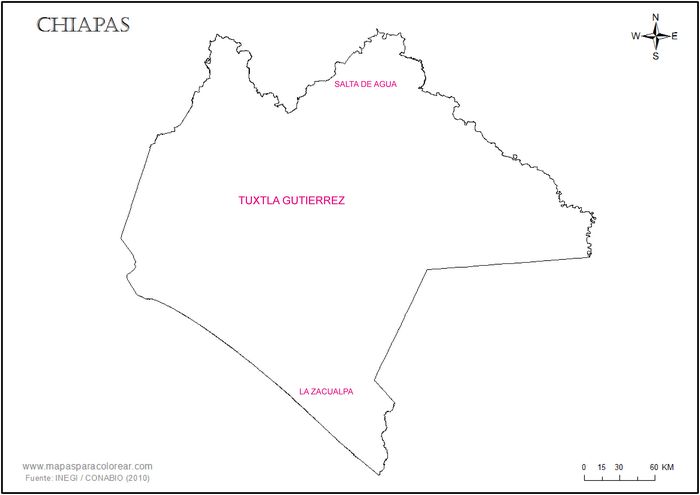

The rubber plantation called La Zacualpa was located in the coastal jungle of the Soconusco department of Chiapasfor details see Peter V. N. Henderson, “Modernization and Change in Mexico: La Zacualpa Rubber Plantation, 1890-1920” in The Hispanic American Historical Review, Vol. 73, No. 2 (May, 1993), pp. 235-260.

Formed in the mid-188os, the La Zacualpa-Hidalgo Rubber Corporation, a Nevada corporation with its headquarters in San Francisco, represented both British and U.S. interests. Its principal shareholder and one of its directors, a British citizen named Oliver Herbert Harrison, invested millions of dollars in the company. He and corporate president E. R. Stackable, an American, sent one William Fisher and a colleague to clear the jungle and plant approximately 18,000 acres of castilloa elastica, the domestic Mexican rubber tree, on the property. The corporation reserved the remaining 12,000 acres for immediate use as pasturage and future development.

On La Zacualpa, management purchased workers with debts of up to one thousand pesos and maintained individual debt totals in the ledgers of the tienda de raya. Workers could also make purchases on credit; therefore the evidence is clear that debt peonage existed on La Zacualpa during the Porfiriato and the early revolutionary period. Whether the peonage helped or hurt the workers, the available records do not tellGovernor Rabasa in 1893 criticized indebted servitude, reasoning that it paralyzed substantial amounts of capital that could be more efficiently employed, and therefore was prejudicial to both servants and landowners. With some landowner support Rabasa's successor, Governor Francisco C. León, held an agricultural congress in 1896 to resolve the question of indebted servitude. There is no question that León wished to rid Chiapas of what he called 'this vicious and spineless custom'. The governor, however, failed to convince both President Díaz and a majority of the delegates to the congress of the benefits of its immediate suppression. One delegate, reflecting the views of the majority, noted that 'there is no doubt that servitude is hostile to progress; but one cannot suppress it all at once, because this will bring worse wrongs.' The congress led to a state-wide survey of indebted servitude which revealed the pervasive character of the institution. The survey found that there were 38,000 indebted servants in Chiapas who owed, collectively, more than 3 million pesos to their employers (Periódico Oficial, 30 July 1898). Indebted servitude remained the most important labour system in the state until it was officially abolished in 1914..

The Revolution affected La Zacualpa through the reformist legislation enacted by Governor General Jesús Agustín Castro between October and December 1914. The most important bill, the Ley de Obreros (Workers' Law) of 30 October 1914Periódico Oficial, Tomo XXXI, Núm. 104, 31 October 1914, mandated changes in agrarian labour practices statewide. Castro's legislation, which was apparently drafted following a brain-storming session with other Constitutionalist leaders, abolished debt peonage in Chiapas. Landlords could no longer use the courts to collect a peon's debts. Agricultural wages had to be paid in cash, not scrip or merchandise, and the statute established a variable minimum wage according to district. Field labourers were not permitted to work more than ten hours a day, and they received a form of workers' compensation if injured on the job. The law also abolished the debt-collecting mechanism of the tiendas de raya, and allowed peones to use the landlord's water and firewood. Peones could also graze as many as six head of cattle or horses on an estate. The landlord had to provide housing, medical attention, and free schooling for all children resident on the estate, who, moreover, were barred from working. If the landlord violated any of these provisions, the statute threatened prison terms, fines, and even confiscation of the estate. As an additional enforcement mechanism, the law established special commissions under the jurisdiction of local military commanders that made bimonthly, random inspections of estates. In exchange for these benefits, the law obligated the peones to work honestly and energetically.

Among the archives that were thrown into landfill by the new owners of the American Bank Note Company was correspondence from 1914 for notes for the Zacualpa Hidalgo Rubber CoABNC, 40238.00. These will have referred to an issue contemplated (and possible effected) during the revolution.

Lumija

The American-owned Lumija plantation, on the Tulija River in the department of Palenque, was reported to be one of the most fertile spots in Mexico. It was being developed in 1900 and it was expected that within the year about 250 acres in coffee trees, 200 acres in rubber plants, and 5,000 new lemon trees and 10,000 new orange trees would be set out. The plantation also cultivated ginger, vanilla, pineapples and other tropical fruitsMonthly Bulletin of the American Republics, Vol. IX, Num. 1, 1900.

On 12 April 1915, C. G. Rieb, the plantation's manager, called on the American consul in Frontera, Tabasco, and reported that he had been fined $500 in Mexican currency for issuing small denomination “due bills” in order to supply his laborers with change (which was unobtainable in that remote area), and that he would be imprisoned on the following day at 4 p.m., unless the fine was paid. Apparently the workers were perfectly willing to receive the notes as they enabled them to deal with the plantation store where they could buy cheaper supplies than from the stores in the adjoining villages. The notes were regularly redeemed every week, if they were not used by the labourers. In order to persuade the authorities they had appointed a committee to call on the Inspector of Plantations at Salto de Agua, Chiapas, about three miles from the plantation, to request him to allow the manager to continue the issue but the Inspector had refused to grant their request.

The Frontera consul, A. J. Lepinasse, added that “due bills” were issued by all the leading plantations in Chiapas. Unless they were permitted to do so they would be compelled to close down, which would be a severe blow and great loss to the American plantations in ChiapasSD papers, 812.515/39.

John R. Silliman, the American consul at Veracruz, took the matter up with the Secretary of Foreign Affairs who in turn raised the matter with the State Governor. On 21 April Rieb telegraphed that he had sorted out his difficulty with the authorities and no further action was required.