Mining scrip and other abuses

Yedras

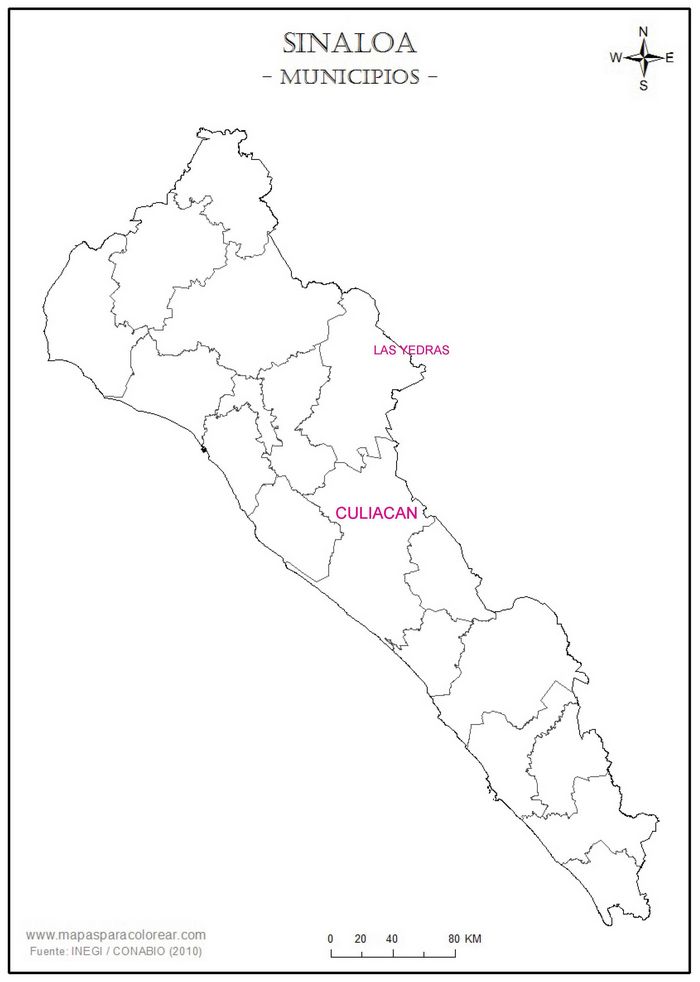

The Anglo-Mexican Mining Company Limited was formed in England in 1883 to purchase from the Yedras Mining Company of New York, the Yedras silver mine, mill and plant in Badiraguato and a large tract of land surrounding the mineSouth Wales Daily News, No. 3703, 15 January 1884. The mine was located about 130 kilometres north of Culiacán.

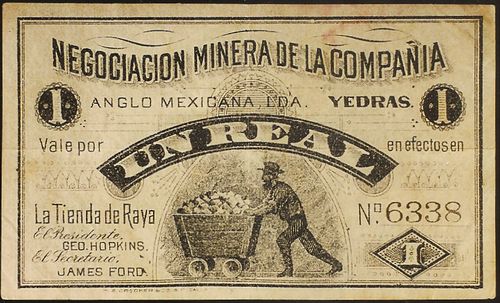

M748 1r Yedras

M748 1r Yedras

| from | to | total number |

total value |

||

| 1r | includes number 6338 |

In 1886 a newspaper reported that the company had established a tienda de raya, operating a monopoly and charging excessive prices for its goodsEl Diario del Hogar, 4 April 1886 The report says that the company was American. This 1 real vale for goods in the tienda de raya has the names of George Hopkins as Presidente and James Ford as Secretario, both of whom were based in London, England, and was produced by H. S. Crocker & Co., of San Francisco, California.

|

George Hopkins was the chair of the board of directors of the company since its creation. He was a London-based civil engineer and mining promoter, who by 1893 acted not only as chairman of two Anglo-Mexican gold and silver mining enterprises (this Anglo-Mexican Mining Company Ltd. and the Princesa Gold Mining Company Ltd.), but also as chairman of twelve and as director of another two British free-standing companies active in Australia, South Africa, Canada, the USA, Peru, and Uruguay. Hopkins's companies were mostly gold and silver mines, but also included a lead-mining and a land-development enterprise. To provide labour for the Anglo-Mexican Mining Company, Hopkins contracted with a Hong Kong firm, which promised to ship Chinese coolies to the mining camp via Mazatlán and Guaymas. Problems plagued this project from the start. An early group of 300 Chinese arrived in Mazatlán in the summer of 1886. They lived in two rooms in a building in the centre of the town while they awaited the arrival of the mining company's agents. Local authorities accused the contractors of maltreating the coolies. Living in poverty and hunger, eating discarded watermelon rinds, they were finally provided rotten fish and a paltry supply of rice by the townspeople. Finally the company removed the coolies to the mines. Of the 300, about one half obtained employment. If they were healthy and capable after their ordeal in the city, they obtained jobs in the mines at wages up to a peso and a half a dayEl Tiempo, Año III, Núm. 858, 29 June 1886; Año III, Núm. 858,1 July 1886; Año III, Núm. 872, 16 July 1886; SD Papers, microcopy 159, reel 5, E. G. Kelton, United States Consul, Mazatlán, to the Secretary of State, 1 December 1886. A second group of Chinese arrived in Mazatlán from San Francisco in October 1886. No company agent met them, therefore, some left for other areas of Sinaloa and Sonora in violation of their contracts. At their own expense city authorities fed and housed the remainder. The 150 Chinese barely survived on clams and crayfish that they caught. Finally, when some Chinese died, the populace, moved by their misery, donated twelve centavos a day for their relief. They expected the Chinese consul in San Francisco to reimburse them. Representatives of the company soon arrived and took the Chinese to the camp at YedrasEl Socialista, Año XVI, Tomo XVI, Núm. 46, 31 December 1886; El Monitor Republicano, Año XXXVII, No. 73, 26 March 1887).. George Hopkins was still chairman of the Anglo-Mexican Mining Company and based in England from 1896The Mexican Herald, 29 June 1896 to 1899The Mexican Herald, 13 January 1899. |

|

| James Ford was the secretary of the company since its creation, based at temporary offices at 5 Old Broad Street, London. |

Following the law of 30 November 1889 forbidding the use of scrip, on 11 June 1891 the superintendent of the company, Algernon Sydney Jones wrote to the Ministro de Fomento asking for an exemptionSuprema Corte de Justicia de la Nácion, Ignacio I. Vallarta, Archivo Inédito, 131. He explained that the mine was six days travel from Culiacán, five from the district capital, Badiraguato, and twelve from Chihuahua with no important town nearby. The company therefore paid daily, to attract employees, but there was a lack of fractional currency, since the Culiacán mint was not producing much, and the employees, when moving on, took the money that they had been paid with them. So the company paid in fichas, to be exchanged for hard cash, whenever the stage arrived from Culiacán every one or two weeks, but never abused this system. The new law made the current practice impossible and threatened to leave the mine without workers so Jones asked for an exemption.

On 5 September 1892 Morlett, Ituarte y Compañía made a complaint to the Supreme Court over the use of fichas to pay the workers at the mineArchivo Ignacio L. Vallarta, 1337. But on 5 December 1893 the company asked the Secretaría de Hacienda if it could continue using fichasArchivo Ignacio L. Vallarta,1407 so it seems that it employed the usual stratagem of dragging the matter out as long as possible.

By 1896 the mine had been closed because of the continuing losses it had sustainedThe Mexican Herald, 29 June 1896.

Other instances

On 30 September 1907 a Mazatlán newspaper, El Demócrata, carried a long article by Enríquez Martínez Sobral attacking the system of fichas, by which workers, on requesting an advance, were paid not in dinero but in ‘“fichas,” vales, tarjetas, planchuelas ú otros signos que naturalmente, no son de recibo en ninguna parte’ to be used in the tienda de raya. Or workers were paid in fichas and never saw a coin, so that they had to return their wages in purchases with the patrónEl Demócrata, Mazatlán, Tomo II, Año II, Núm. 449, 30 September 1907.

On 18 June 1911 in a letter to El Correo de la Tarde, Juan Manuel Banderasfor Banderas's life, see Saúl Almando Alarcón Amézquita, Juan M. Banderas en la Revolución, Universidad Autónoma de Sinaloa, March 2006 denounced the oppression felt by mine workers who received their wages not in legal tender but in vales for the tienda de raya. In addition he enclosed a copy of a notice that the Junta Militar had sent to the governor, about the payments that mining companies made with ‘boletos de crédito'El Correo de la Tarde, 18 June 1911.