DeWitt's Colony

In the hopes that an influx of settlers could control Indian raids the newly independent Mexico liberalized its immigration policies for the north of the country and settlers from the United States were permitted in the colonies for the first time.

In 1822 Green Dewitt petitioned the Mexican government for permission to settle colonists in Texas but was denied. He was inspired to try again after the passage of the Ley General de Colonización (General Colonisation Law) on 28 August 1824 and after having met the earlier empresario, Stephen F. Austin, with whom he continued to have a close relationship. Austin's influence, together with Baron de Bastrop’s, helped DeWitt to petition the Mexican government successfully, on 7 April 1825, for an empresario contract to settle "four hundred industrious Catholic families...known to be respectable and industrious," and also any equally respectable families of Mexican nationals who "shall come to settle with us." On 15 April the government in Saltillo, Coahuila, gave him permission to settle in an area bounded by the Guadalupe, San Marcos and Lavaca Rivers. DeWitt’s surveyor, James Kerr, chose to place the capital, called Gonzales after Rafael Gonzales, provisional governor of Coahuila y Tejas, at the confluence of the San Marcos and Guadalupe Rivers.

By 1828 the colony consisted of 11 families and 27 single men. Most were primarily from the southern states, with some coming from as far north as New York. By 1829 the colony had experienced a boom, expanding to 30 families and 34 single men. By 1830, it had 56 families, and 65 single men. On 6 April 1830 the Mexican authorities passed a law prohibiting further immigration to Texas from the United States. Austin was able to secure a waiver for DeWitt's colony, but the measure made it difficult for him to recruit families. When his contract expired on 15 April 1831, he had settled a total of 166 families.

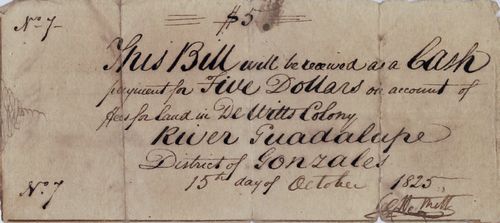

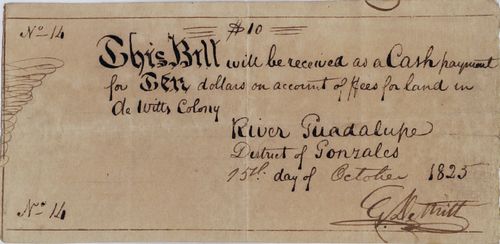

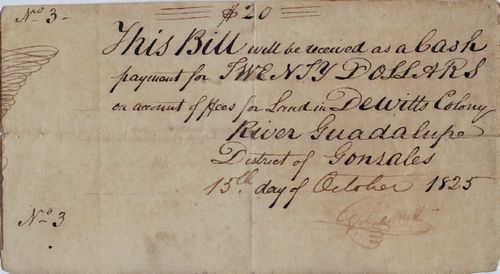

In the colony "‘Money was as scarce as bread. There was no controversy about “sound” money then. Pelts of any kind passed current and constituted the principle medium of exchange” Noah Smithwick, The Evolution of a State, or, Recollections of Old Texas Days, 1900. DeWitt did issue, however, what was essentially land scrip in denominations of five, ten, and twenty dollars, for his colonists to buy their lands, with the legend ''This Bill will be received as a Cash payment for ... Dollars on account of fees for land in DeWitts Colony.'' This handwritten currency was transferable and generally passed as a medium of exchange.

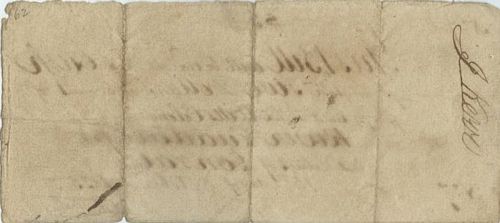

M679.1 $5 DeWitt's Colony

M679.1 $5 DeWitt's Colony

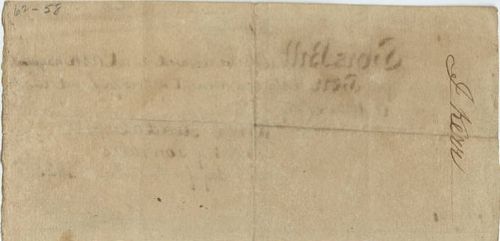

M679.2 $10 DeWitt's Colony

M679.2 $10 DeWitt's Colony

M679.3 $20 DeWitt's Colony

M679.3 $20 DeWitt's Colony

| date on note | from | to | total number |

total value |

||

| $5 | 15 October 1825 | 1 | includes number 5 | |||

| $10 | 1 | includes number 14 | ||||

| $20 | 1 | includes numbers 3 and 4 |

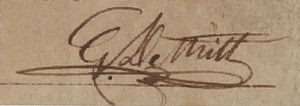

These notes were signed by DeWitt. The $5 and $10 notes are endorsed on the back by James Kerrimages from DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University.

|

Sara Seely DeWitt contributed to her husband's venture with the profits from the sale of her property in Missouri. By October 1825 Green DeWitt was inspecting the work already done in his colony by his surveyor, James Kerr. After a few weeks he returned to Missouri to promote the colony. By April 1826 he was bringing to Texas his wife, two sons, three of four daughters, and three other families. The group joined those already in the colony, who eventually settled at Gonzales. For almost the next decade DeWitt worked to develop the colony. As his contemporary, Noah Smithwick, later said of the empresario, he "was as enthusiastic in praise of the country as the most energetic real estate dealer of boom towns nowadays." Because the Mexican government had not specified a boundary between DeWitt's grant and the earlier grant made to Martín De León further south on the Guadalupe River, the two empresarios had numerous disputes involving boundaries and contraband trade, resulting in irreparable damage to their relationship. DeWitt apparently did not have the degree of personal influence over his settlement that Austin exercised at San Felipe. Although he represented the District of Gonzales in the Convention of 1833, he never held an elected office in the colony's government. Despite his apparent success in establishing the colony, he was unable to fulfil his contract by the time it expired on 15 April 1831, and he failed to get it renewed. He spent his last years engaging in some limited commercial investments and improving his own land on the right bank of the Guadalupe River across from the Gonzales townsite, premium land given him as empresario. For the most part, however, his colony proved neither materially nor financially rewarding for him. He had apparently invested all his family's resources in his struggling colony, and as early as 1828 its problems compelled one visitor, though impressed with the empresario, to note that "dissipation [and] neglectful indolence have destroyed his energies." Indeed, DeWitt endorsed his wife's petition in December 1830 to the ayuntamiento of San Felipe de Austin asking for a special grant of a league of land in her maiden name "to protect herself and family from poverty to which they are exposed by the misfortunes of her husband." The Mexican government complied in April 1831. In an attempt to improve his economic position and to secure premium land for settling eighty families, DeWitt journeyed in 1835 to Monclova, where he hoped to buy unlocated eleven-league grants from the governor, who was attempting to raise money for defence through land sales. But he failed to acquire any land. While in Monclova DeWitt contracted a fatal illness, probably cholera. He died on 18 May 1835 and was buried there in an unmarked grave. Though he did not live to see the battle of Gonzales, which traditionally is considered the first skirmish of the Texas Revolution, his wife and daughter, Naomi, cut up Naomi's wedding dress to make the "Come and Take It" banner that his fellow colonists adopted as their battle flag. |

|

|

In January 1825 Kerr was appointed surveyor general of the Green DeWitt colony. In April or May he took his family and about eight slaves to Brazoria, where he joined the colony of his close friend, Stephen F. Austin. Later that year his wife and two of his children died of cholera at their camp on the San Bernard River. Leaving his surviving three-year-old daughter with friends in San Felipe, he set out with Erastus (Deaf) Smith and five other men to select a site for the capital of the DeWitt colony. In August 1825 the men built cabins on Kerr's Creek near the junction of the San Marcos and Guadalupe rivers and made plans for the establishment of Gonzales. The next year the makeshift huts were destroyed by Indian raiders. In January 1827 Kerr acted as attorney and surveyor for Benjamin Rush Milam. The same year Austin dispatched Kerr, James Cummins, and Richard Ellis to Nacogdoches to attempt to persuade Haden Edwards to abandon his Fredonian Rebellion. In May 1827 Kerr signed a treaty with the Karankawa Indians. The same month, as one of the Old Three Hundred, he received title to a league now in Jackson County. He settled this holding and reportedly brought in the first crop in the county. The Kerr cabin became a centre where new settlers were routinely greeted and entertained. On 15 December 1830, the ayuntamiento of San Felipe de Austin ordered a favourable report on Kerr's petition for additional land because of services he had rendered for the public good. Kerr was the Lavaca delegate at the Convention of 1832. The next year, as a member of the Convention of 1833, he made a memorandum of the full list of representatives; he also took enough time from public service to marry Sarah Fulton, a foster daughter of John J. Linn. In June 1835 Kerr reported the political news in Mexico and the rise of Antonio López de Santa Anna to Gail Borden, Jr. In October 1835 Austin wrote Kerr requesting that he and John Alley sign a letter to the American colonists of Texas confirming the advance of Gen. Martín Perfecto de Cos and his Centralist army. Kerr was elected a delegate to the Consultation of 1835 but did not serve because he was involved in a campaign against the Lipan Apaches. He later won appointment to the Consultation as a member of the General Council, in which capacity he was author of the decree appointing Sam Houston, John Forbes, and John Cameron to negotiate a treaty with the Cherokees. Kerr was elected a delegate to the Convention of 1836, but there is no record of his attendance. During the period of the republic Kerr represented Jackson County in the House of the Third Congress and introduced antidueling legislation and a bill to make Austin the capital. Though he was admired and respected by his associates, even his family members admitted that he was not much for looks. One day when he was visiting a saloon, a homely stranger approached him and announced, "I'm sorry, but I'm going to have to kill you." Kerr calmly asked the man why such drastic action was necessary, whereupon the visitor explained, "I have always said if I ever saw a man uglier than I am, that I was going to shoot him." Kerr invited the man over to the window and, after inspecting the man in the daylight, wryly commented: "Shoot away, stranger, if I'm any uglier than you I don't care to live!" Kerr spent his last years practicing medicine. On 25 December 1850, he died in his Jackson County home. |

|

The fact that these notes were denominated in U. S. dollars rather than Mexican pesos was one of several indicators, including the presence of black slaves (in violation of Mexican law), that the U. S. immigrants did not sincerely embrace their new Mexican citizenship.

Green DeWitt was born on 12 February 1787, in Lincoln County, Kentucky. While he was still an infant, his father moved the family to the Spanish-held territory of Missouri. Although little is known of his father's activities there, the family was prominent enough to educate Green beyond the normal rudimentary level, and when the boy turned eighteen he returned to Kentucky for two years to complete his education. He then returned to Missouri, where he married Sarah Seely of St. Louis in 1808. DeWitt enlisted in the Missouri state militia in the War of 1812 and achieved the rank of captain by the war's end. He then served for a time as sheriff of Ralls County. In 1821 he was inspired by Moses Austin's widely circulated success in obtaining a grant from the Spanish government to establish a colony in Texas. As early as 1822 he petitioned the Mexican authorities for his own empresario contract but was unsuccessful. Having seen Texas and visited Austin, DeWitt journeyed in March 1825 to Saltillo, the capital of the Mexican state of Coahuila and Texas, where he petitioned the state government for a land grant. Aided by Austin and the Baron de Bastrop, he was awarded an empresario grant on 15 April 1825, to settle 400 Anglo-Americans on the Guadalupe River and was authorized to establish a colony adjacent to Stephen F. Austin's subject to the Colonization Law of 1824. He was accused of having misappropriated public funds in Missouri by Peter Ellis Bean before the jefe político at San Antonio shortly after he received his grant, but was exonerated on 16 October 1825, after Stephen F. Austin investigated the matter.

Green DeWitt was born on 12 February 1787, in Lincoln County, Kentucky. While he was still an infant, his father moved the family to the Spanish-held territory of Missouri. Although little is known of his father's activities there, the family was prominent enough to educate Green beyond the normal rudimentary level, and when the boy turned eighteen he returned to Kentucky for two years to complete his education. He then returned to Missouri, where he married Sarah Seely of St. Louis in 1808. DeWitt enlisted in the Missouri state militia in the War of 1812 and achieved the rank of captain by the war's end. He then served for a time as sheriff of Ralls County. In 1821 he was inspired by Moses Austin's widely circulated success in obtaining a grant from the Spanish government to establish a colony in Texas. As early as 1822 he petitioned the Mexican authorities for his own empresario contract but was unsuccessful. Having seen Texas and visited Austin, DeWitt journeyed in March 1825 to Saltillo, the capital of the Mexican state of Coahuila and Texas, where he petitioned the state government for a land grant. Aided by Austin and the Baron de Bastrop, he was awarded an empresario grant on 15 April 1825, to settle 400 Anglo-Americans on the Guadalupe River and was authorized to establish a colony adjacent to Stephen F. Austin's subject to the Colonization Law of 1824. He was accused of having misappropriated public funds in Missouri by Peter Ellis Bean before the jefe político at San Antonio shortly after he received his grant, but was exonerated on 16 October 1825, after Stephen F. Austin investigated the matter. James Kerr was born near Danville, Kentucky, on 24 September 1790. In 1808 his Baptist minister father moved the family to Missouri. Kerr fought in the War of 1812 under Nathaniel Boone and achieved the rank of lieutenant. Thereafter he was sheriff of St. Charles County, Missouri. In 1819 he married Angela Caldwell and moved with his bride to Sainte Genevieve, Missouri. He served two terms in the House and one in the Senate as a representative of the Sainte Genevieve district.

James Kerr was born near Danville, Kentucky, on 24 September 1790. In 1808 his Baptist minister father moved the family to Missouri. Kerr fought in the War of 1812 under Nathaniel Boone and achieved the rank of lieutenant. Thereafter he was sheriff of St. Charles County, Missouri. In 1819 he married Angela Caldwell and moved with his bride to Sainte Genevieve, Missouri. He served two terms in the House and one in the Senate as a representative of the Sainte Genevieve district.