Scrip of textile mills

La Compañía Industrial de Orizaba

La Compañía Industrial de Orizaba S.A. (CIDOSA) was formed in 1889 with capital from Thomas Braniff, and the BarcelonnettesBarcelonnette is a subprefecture in the department of Alpes-de-Haute-Provence, located in the southern French Alps. Between 1850 and 1950, it was the source of a wave of emigration to Mexico, including some who went on to develop department stores and other businesses. On the edges of the towns of Barcelonnette and Jausiers there are several houses and villas of colonial style (known as maisons mexicaines), constructed by emigrants to Mexico who returned to France between 1870 and 1930. Ollivier y Cía (Ciudad de Londres), J. Tron y Cía (Palacio de Hierro)The El Palacio de Hierro department store was born from a company created in 1879 by Joseph Tron who had acquired the store Las Fábricas de Francia, founded in 1850 by the firm Gassier Reynaud y Sucs. In 1888 Tron founded the limited-liability joint-stock company (sociedad anónima) El Palacio de Hierro, which eventually became Mexico's largest department store. At first, it operated on a small lot, but Tron then built a five-story building designed by a French architect with iron structures, similar to those of the Eiffel Tower, and with an area of more than a thousand square metres. It was inaugurated in June 1891. By 1900 it had been extended to 2,600 square metres. It became a highly profitable enterprise, reporting a 15 percent profit in 1904,and Signoret, Honnorat y Cía (Puerto de Veracruz). and in the next ten years it acquired and constructed four textile factories in the Orizaba valley: Cerritos, San Lorenzo, Río Blanco and Cocolapan (acquired in 1899).

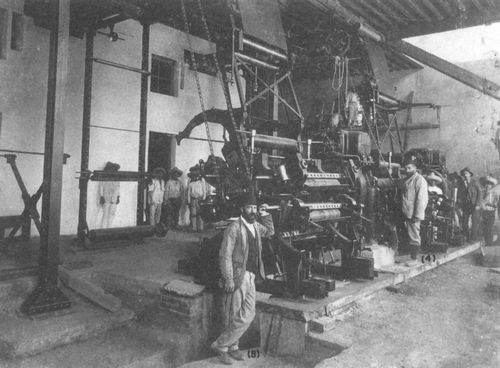

The Rio Blanco factory was built to supply the owners’ department stores in Mexico City and other major cities throughout the country. With more than 40,000 spindles and almost 2,600 workers, it was the largest textile mill in the country and was large even by international standards. Like most textile mills in Mexico, it was originally built on an unpopulated site that was eventually transformed into a company town.

Another way in which the Compañía Industrial de Orizaba's partners earned income, from the foundation of their factories until 1912 were the tiendas de raya (company stores). These businesses served the entrepreneurs to recover part of the wages of the workers, by forcing them to buy in them the food, clothing and other goods they needed. They existed in the San Lorenzo Factory, in Río Blanco and Santa Rosa. The tiendas de raya received the vales issued by the textile companies as an advance of the salary at the request of the worker. Vouchers could be redeemed for goods or for money at 90% of their value. The following Saturday the amount advanced to the workers was deducted from their salaries to pay the debt.

Río Blanco’s company store was leased to Victor Garcín, a Barcelonnette who had been in the region for some decades. Eduardo Garcín, his brother, was the Compañía Industrial de Orizaba manager in 1903 and a member of the board in 1905 and 1906. However, Garcín’s store was not merely a company store. He seems to have run the largest store in the area, occupying a whole block, and sold not only directly to workers but also to several stores in the region. Besides Río Blanco’s company store Garcín owned two other stores: “El Centro Comercial” at Nogales, and “El Modelo” at Santa Rosa, and nine pulquerías which also held billiard tables.

After the conflicts of 1907, where the workers burned the tiendas of Victor Garcín, he decided to sell his property to Manuel Diez and left the area.

La Compañía Industrial Veracruzana S.A.

The Santa Rosa textile factory

After the Compañía Industrial de Orizaba was created, several owners of dry-goods stores decided to enter textile production by becoming partners of manufacturing companies. The Compañía Industrial Veracruzana S.A. (CIVSA) was founded in 1896 as a limited-liability joint-stock corporation by several Barcelonnette entrepreneurs under the leadership of Alejandro Reynaud. The Compañía Industrial Veracruzana inaugurated a new factory in 1898, the Santa Rosa, which became the second-largest mill in the country, and, like Rio Blanco, had the latest technology, including hydroelectric power.

In 1897, when the Santa Rosa mill was still under construction, the Cía Industrial Veracruzana board decided that there was an urgent need to establish a provisional store since there were no commercial facilities in the surrounding area. The store was necessary so that workers “do not lack what they need or waste time by having to go to find it as far away as Orizaba.” It seems that other than the store at Nogales that served the Cía Industrial de Orizaba’s San Lorenzo factory, there were no stores except in Orizaba, eleven kilometres away from Santa Rosa. So, before the mill started operating, the board of directors consulted some Orizaba storekeepers, Cabrand y Caffarel and Gilberto Fuentes to see whether they would establish such a store, “by their own means and without commitment on the part of the company.” As early as December 1896, Caffarel had asked the board to grant the company store’s concession to Donnadieu y Caffarel of Nogales but the board decided to postpone the decision because there were several bidders for it. In April 1897, the company began the construction of the store at the corner of the roads to Nogales and Necoxtla and by early January 1899 construction was nearly completed. The Cía Industrial Veracruzana board decided to lease it to Gilberto Fuentes, in exchange for $150 per month and a 5% commission on the weekly discounts they made at the workers' credit for buying merchandise in the store. The store remained leased to the Fuentes family for several decades. After the conflicts of 1907, the partners ordered the Director General of the Santa Rosa factory to void any obligation of the company to the tienda.

The role of the tienda de raya

(Much of the following section is taken from Aurora Gómez-Galvarriato, Myth and Reality of Company Stores during the Porfiriato: The tiendas de raya of Orizaba's Textile Mills, presented in the XIV International Economic History Congress, 21 to 25 August 2006, Helsinki, Finland)

According to the prevailing view, company stores were opened because they yielded a double benefit to their owners. First, through company stores employers were able to extract extra benefits from the already low wages. Second, by keeping workers indebted, they could prevent their work force from moving into other jobs that could offer them better conditions. However, the discussion of the Cía Industrial Veracruzana board posits a different reason, namely to provide workers with a nearby place to buy their necessities. These reasons must have been shared by other enterprises. When haciendas, mines, or mills first established in a region, their population was initially too small for an independent store or housing area to be profitable, thus company provision of stores and housing was considered a necessity. Another reason for establishing a monopoly was to prevent competition that would lower benefits including the rent that could be charged.

From what we can learn from the Cía Industrial Veracruzana S. A. and the Cía Industrial de Orizaba S. A. records, we know that company stores were not run directly by the employer but operated under concessions granted to third parties. The employer was responsible for deducting workers’ debts to the store from their weekly wages. In compensation for this duty, the employer received a percentage of what the workers spent at the store.

In the Orizaba textile mills, workers were paid most of their wages in silver coins as we know from the weekly letters that came and went from Mexico City to the mills demanding large amounts of coins to pay weekly wages, or reporting on their remittance or arrivalArchivo de la Compañía Industrial de Orizaba, Correspondence, A. Reynaud to Río Blanco, several letters: Archivo de la Compañía Industrial Veracruzana, Correspondence, MX-SR, 30 August 1910. From August to December 1906, 18 letters of the Compañía Industrial de Orizaba report that the office in Mexico City sent by express $3,000 pesos in “tostones” for the weekly payroll (rayas). From January 1907 to March 1908 29 letters reported they sent $5,000 pesos weekly, also mostly in “tostones” .

In the Orizaba valley scrip, or vales, were an advance on wages due the following payday. It was negotiable at the company store at its full value if it was traded for merchandise, or at 70 percent or 80 percent of its value if it was exchanged for money. On the following Saturday, the amount advanced to workers in scrip during the week was deducted from their wages and paid to the company store, after deducting five per cent commission. This general procedure appears to have been common to company stores throughout the world at the time.

Numerous accounts tell that company stores deducted a certain percentage of the value of these vales. It is not clear whether these accounts refer to the discount made when exchanging scrip for money, or when purchasing at the store with scrip, although the former seems more plausible. We should understand this discount as the interest rate the company store charged for the credit it gave, minus the five per cent it paid in commission to the mill.

It is possible that in some textile mills workers were fully paid in scrip, since several newspaper articles denounced this practice, yet no study has yet found evidence in hacienda or company records of such a case. It is difficult to trust these accounts given that it also common to find articles that indicate that in the Compañía Industrial Veracruzana S. A. and Compañía Industrial de Orizaba S. A., workers were paid only in scrip, while hard evidence tells this was not true. Thus, an article in El Hijo del Ahuizote, on 5 April 1903, for example, said that the Santa Rosa workers were paid with cardboards or tokens, so that they buy at the company storeEl Hijo del Ahuizote, 5 April 1907. Newspaper articles that appeared in the following days of the 7/8 January massacre, generally agreed that workers in Río Blanco were paid only in scripSee for example El Diario del Hogar, 9 January 1907, "Obreros Sublevados en Río Blanco y Nogales Incendian una Casa de Comercio”.

On 15 January 1907, El Diario published an article stating that it was urgent that the system of company stores was modified. The article said that while the law forbade payment through tokens and that there had been several cases where violations to this rule had been punished, it was easy to make a mockery of these regulations through the company stores. The worst damage caused by company stores, according to the article, was that they gave credit to workers through the system of vales. This was terrible since credit “was very dangerous when given to individuals not very reflective and of a light temperament, as our workers frequently are.” Thus, the largest share of wages never went to the workers but entered directly to the company stores who charged higher prices on the “advanced” merchandise and high discounts (of between 12 percent and 25 percent per week) on vales as interest rate. Even worst was the fact that the debts that workers held with company stores were mostly due to buying alcoholic drinks, the most profitable part of their business. The article urged for new legislation that prohibited the issue of vales by private establishments, and the regulation of company storesEl Diario, Vol II, Núm. 95, 15 January 1907, “Es Muy Urgente que se Modifique el Sistema de Tiendas de Raya”.

La Semana Mercantil, a business journal, took a similar stance blaming the tiendas de raya for the violence that took place on 7 January. “The conflict between the interests of the industrial and the worker were not the cause of the conflict” claimed the journal, but the abuses inflicted upon workers by the company stores. “The company stores […] are harmful to workers […] by negotiating the vales of credit [...] they open the way for squandering and vice, and these same evils are the foundation of their prosperity and profits.”La Semana Mercantil, 2ª, Época, Año XXIII, Núm. 3, 21 January 1907, “Los Sucesos de Río Blanco II” While company stores could not be forbidden, since that would have gone against the freedom of trade La Semana Mercantil proposed that the payment of wages in vales should be proscribed in order to prevent the repetition of deplorable events such as those that took place in the factories nearby OrizabaLa Semana Mercantil, 2ª, Época, Año XXIII, Núm. 4, 28 January 1907, “Las Tiendas de Raya”.

In his book Barbarous MexicoJohn Kenneth Turner, Barbarous Mexico, Chicago, 1910 John Kenneth Turner made an interesting description of Río Blanco’s working conditions. Although he seems to have visited Río Blanco, his article is full of inexact information, such as his claim that there were 6,000 workers at the factory Río Blanco (the correct number is between 2,500 and 3,000 depending on the date). On the tiendas de raya he wrote that workers were paid in vales for the company store instead of coins, and that by the means of the company store the firm recuperated all the money that it paid to its workers. He said that the company charged between 25 percent and 75 percent higher prices than those at which merchandise could be acquired in Orizaba, but that workers were forbidden to buy elsewhere.

More recent studies of the “Río Blanco strike”, such as Bernardo García’s and Rodney Anderson’s books have complemented the information given by newspapers with documents found in other archives, particularly that of Porfirio Díaz. However the explanation of the events that resulted in the January 1907 massacre as a great demonstration of workers’ hate for company stores seems to have prevailed. Bernardo García Díaz wrote that “workers wanted to burn all that they rejected and hated particularly those establishments that incarnated injustice in their eyes: the company stores.”Bernardo García Díaz, Un Pueblo Fabril, 149. Rodney Anderson’s account remarks,

With one important exception, the only buildings deliberately burned that day were the company stores of the textile mills in the area. Forced to buy at the company stores because of their location or because wages were paid partly in discounted script, the workers were often in debt to them and universally believed that they paid high prices for inferior goodsRodney Anderson, Outcasts in their Own Land, Northern Illinois University Press, 2008, p.159.

At the Compañía Industrial Veracruzana S. A. on average only 16 percent of workers used the company store and those who used it carried on average a debt of only 26 percent of their wage. Company stores were an efficient source of credit for workers given that they reduced the risk of providing credit to them, and could have been better credit alternatives to other sources of credit such as pawn shops. Yet it seems that the gains they could make, by facing a lower risk than alternative sources of credit, were not channeled to workers but pocketed by the firms and the company store concessionaires.

In 1912 tiendas de raya were banned by the Convención de Industriales y obreros textiles and in 1914 by the Governor of Veracruz, Cándido Aguilar and by the Constitution of 1917.