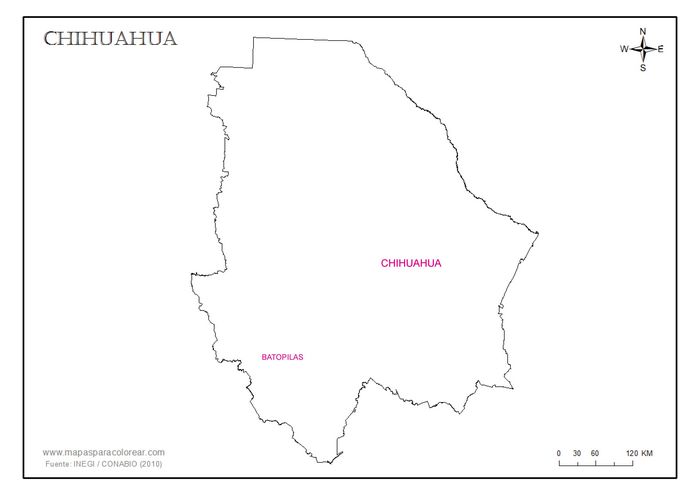

Batopilas

Batopilas is a beautiful little town at the foot of a deep canyon that still retains traces of its former prosperity, brought about by the patronage of Alexander Robey Shepherd.

Batopilas is a beautiful little town at the foot of a deep canyon that still retains traces of its former prosperity, brought about by the patronage of Alexander Robey Shepherd.

|

Alexander Robey Shepherd was born in southwest Washington on 30 January 1835. He dropped out of school at 13 and took a job as a plumber's assistant. Eventually, he worked his way up to becoming the owner of the plumbing firm. He then invested the profits from that firm in real estate development, which made him a wealthy socialite and influential citizen of the city. He was an early member of the Republican Party and a member of the Washington City Councils from 1861 to 1871, during which time he was an important voice for D.C. emancipation, then for suffrage for the freed slaves. President Grant appointed his friend, the financier Henry D. Cooke, as first governor with Shepherd as vice-chair of the city's five-man Board of Public Works. The Board of Public Works was actually an independent entity, reporting directly to Congress, and Shepherd asserted himself as a leader to such an extent that he often did not bother to consult the other members of the Board before he made decisions and took sweeping action. The Cincinnati Enquirer of the time stated "Boss Tweed and his gang, to whom Shepherd's enemies are so given to comparing him, were vulgar villians (sic), stupid sneak thieves, by the side of this remarkable man."Cincinnati Enquirer. Shepherd believed that if the federal government was to remain in Washington, the city's infrastructure and facilities had to be modernized and revitalized. He filled in the long-dormant Washington Canal and placed 157 miles (253 km) of paved roads and sidewalks, 123 miles (198 km) of sewers, 39 miles (63 km) of gas mains, and 30 miles (48 km) of water mains. Under his direction, the city also planted 60,000 trees, built the city's first public transportation system in the form of horse-drawn streetcars, installed street lights, and had the railroad companies refit their tracks to fit new citywide grading standards for the District. In September 1873 Cooke resigned and Shepherd, having befriended Grant, was promoted by the President to the governorship. Once in office, he engaged in a series of social reforms and campaigns that were progressive even by Radical Republican standards. He "integrated public schools, supported the vote for women, sought representation for D.C. in Congress and a Federal payment to the city." Despite the lack of finances, the massive public works project continued and intensified during Shepherd's term as governor of the District of Columbia. However, the cost of the modifications ballooned and an audit revealed that the city was in arrears by $13 million and the legislature declared bankruptcy on its behalf. Shepherd was investigated for financial misappropriation and mishandling, and it was discovered that the project and its funding had been carried to absurd extremes. Although none of Shepherd’s actions was found to have violated any laws, the territorial government was abolished in favour of a three-member Board of Commissioners. Shepherd remained in Washington for a further two years, still a real-estate magnate and a celebrated and influential member of Washington society. In 1876, however, he declared personal bankruptcy and, once his accounts were settled, decided to try his luck at mining. He organised the Consolidated Batopilas Mining Company with a capital of $3,000,000 and purchased 'the Great Batopilas mine' (apparently the San Miguel group), several important mines in the vicinity, surface rights to about 900 square miles of land, mortgages on several farms, a group of large buildings with some smelting machinery, and agencies in Chihuahua and other towns through which to send monthly shipments of silver to New York. In 1880, he moved his family to Batopilas and within a short time had taken over as 'el patron grande'. Because of Batopilas' isolation, Shepherd was a semiautonomous ruler. Always a favourite of President Díaz, in later years he cultivated the friendship of the Terrazas family and Enrique Creel joined his board in 1910. He died in Batopilas on 12 September 1902 from complications of a surgery to remove his appendix. |

|

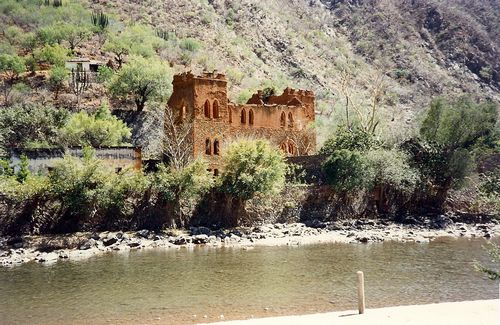

La Hacienda de San Miguel

La Hacienda de San Miguel, situated on the river bank opposite the town, was one of the two main reduction plants which Shepherd made his home and the centre of his operations. By 1902 San Miguel had about ninety stamps, amalgamating pans, cyanide and leaching plants, a machinery shop and a foundry at which the company could make its own castings. The buildings at San Miguel, whose impressive ruins still dominate the town, housed this equipment and also included the main offices, the manager's house, dormitories, a dining room, a swimming tank for employees, and stables for the mules. Around all these stood a high, solid stone wall as protection against floods and robbers.

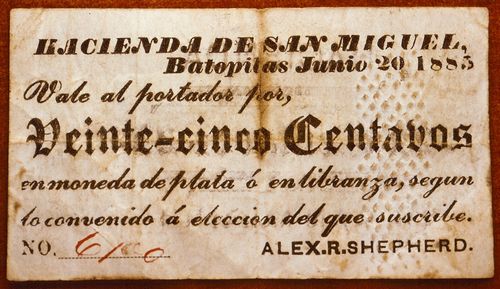

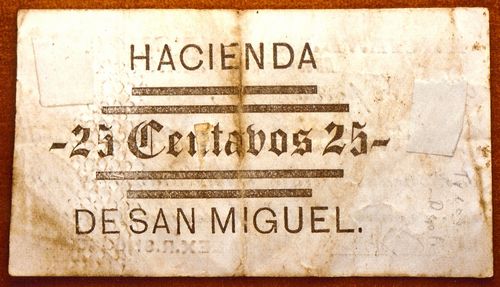

M607 25c Hacienda de San Miguel

M607 25c Hacienda de San Miguel

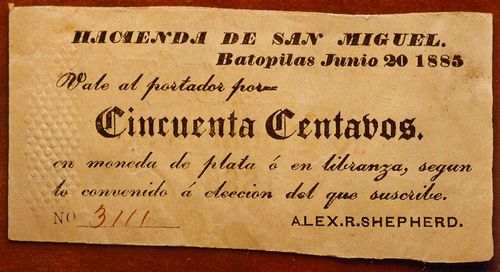

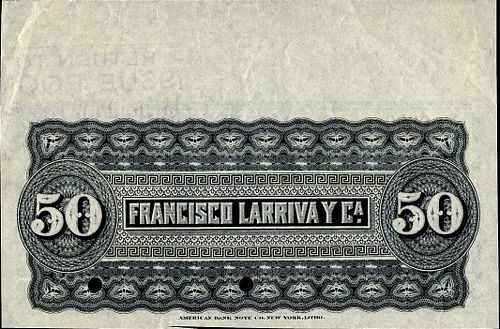

M608 50c Hacienda de San Miguel

M608 50c Hacienda de San Miguel

We know of two notes issued by Shepherd for use on the Hacienda de San Miguel. The notes, for 25c and 50c, have the printed date of 20 June 1885, and were payable to the bearer 'in silver coin or in a bill of exchange according to convenience and at Shepherd's choosing' (en moneda de plata ó en libranza según lo convenido á elección del que subscribe)details and images courtesy of Richard G. Doty, National Museum of American History. These examples were already in the museum (and a star attraction) in 1886.

"Coins of Interest Which Visitor to the National Museum Should Look At.

[From the Washington Star.]

"Do you want to see some of Shepherd's money?" said an attache of the National Museum to a Star reporter. Of course the reporter wanted to see it. The money in question consisted of two bits of paper, about the size of a 60-cent shinplaster. The notes are printed on white paper, in black, without any attempt at ornament, or any of the usual devices to baffle counterfeiters. The notes are dated at Hacienda de San Miguel, Batopilas, and the text upon them is in Spanish. One note is for 25 and the other for 50 cents. In the lower corner is printed the name, Alexander E. Shepherd, well known in this city. A card near the notes informs the curious people who stop to look at them that such notes are in general circulation in Batopilas district, and are preferred by the people there to the paper money issued by the Mexican government. A very extensive collection of coins and- specimens of money has been placed on exhibition in the museum. A curious piece of money is a bit of pasteboard, about the size of a street-car ticket, and marked with a stencil by the man that issued it. The one exhibited is for 3 cents, and was issued by a business house in Mexico. The pasteboard currency has been legalized by the state of Tamaulipas. …" (The Weekly Wisconsin, Milwaukee, 1 May 1886).

There is also a handwritten voucher[image needed] bearing Shepherd's signature and dated 1 September 1886, payable to the bearer (al portador) for five pesos in assayed silver (en plata quintada).

The Batopilas Mining Company

Shepherd set up a tienda de raya which undercut other local retailers, and, like all companies, offered credit to his employees so that only the balance was paid out in cash on Saturday nightGrant Shepherd, The Silver Magnet, New York, 1938. At first his men demanded silver coins, but currency was both expensive and dangerous to bring in. Local merchants refused to accept Chihuahua banknotes, and at their suggestion Shepherd secured permission from the state government to issue his own paper notes.

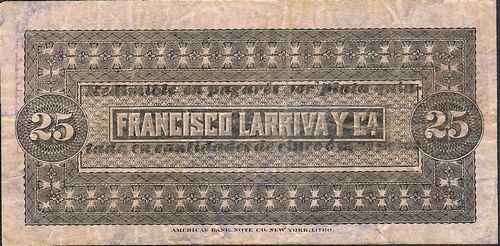

M618a 25c Compañía Minera de Batopilas

M618a 25c Compañía Minera de Batopilas

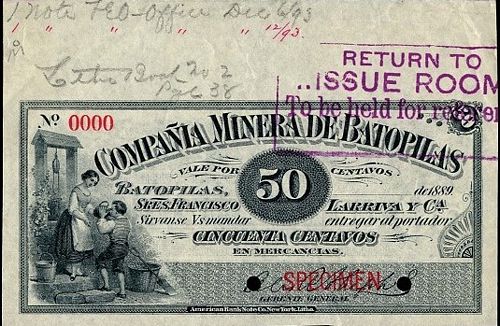

M619s 50c Compañía Minera de Batopilas specimen

M619s 50c Compañía Minera de Batopilas specimen

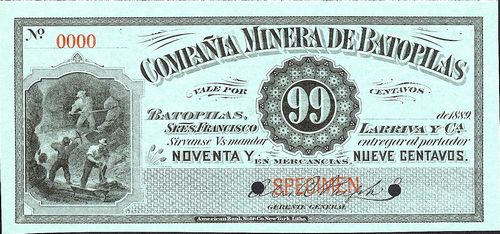

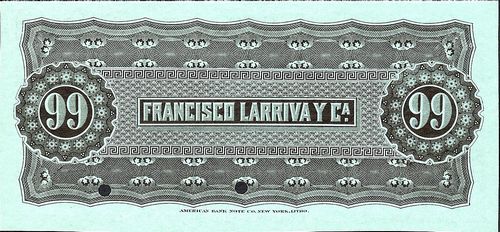

M620s 99c Compañía Minera de Batopilas specimen

M620s 99c Compañía Minera de Batopilas specimen

| series | to | from |

total |

total value |

||

| 25c | A | includes number 11382 | ||||

| 50c | ||||||

| 99c |

The surviving notes of La Compañía Minera de Batopilas (Batopilas Mining Company) are three values printed by the American Bank Note Company, for 25, 50 and 99 centavos, drawn on Sres. Francisco Larriva y Ca.On 5 December 1887 Francisco and Mariano Larriva, of Batopilas, partnered with Enrique C. Creel to found a business venture. Creel invested $3,000 whilst the Larrivas put in the hard work (trabajo y empeño) with profits or losses to be shared equally (AGNCH, protocolo of Antonio Sánchez Aldana, 5 December de 1887). By February 1889 Francisco Larriva had the Batopilas agency for the Banco Minero (AGN, Antiguos Bancos, Actas de Banco Minero, libro 1, 28 February 1888 to 5 January 1899). Francisco Larriva was jefe político of Andrés del Río district from 1898 to 1902 and a deputy in the state legislature. It is probable that this is the same Francisco Larriva who became a leading citizen in Torreón, Coahuila, payable in merchandise (en mercancias) and dated 1889The American Bank Note Company archives record that they were ordered by Felix Bazet. Bazet was born in 1852. A Frenchman who married a Mexican woman, Bazet's profession is given elsewhere as a clerk (dependiente). He came to Chihuahua in 1883 and was living there in 1888.

Shepherd’s notes circulated freely in Batopilas. Upon demand, the company would redeem the notes (in multiples of $5 or more) in hard cash, discounting about 8% for transporting in the coin.

The system also prevented one form of exploitation: “The company has five stores in operation at the five principal mines and at Hacienda San Miguel, where the men can purchase at fixed rates the year round and not be subject to discount on the vales of the company. This was found to be necessary to prevent extortion by persons who discounted vales at 20 to 30 per cent. and the plan has worked perfectly"The Boston Herald, 10 March 1894. The gross sales of the stores amounted to $58,530.44 for the year, and the profit was $6,162.21. The profit from exchange of vales for drafts was $15,102.52.

On 30 November 1889 President Díaz prohibited the use of vales by private companies. By the end of 1889 Shepherd suspended the issue of low denomination vales but then produced another series, after supposedly consulting with local businesses. A $5 note[image needed], dated 28 January 1890, had the legend: “Num. . – Pagaré al portador cinco pesos en plata quintada por su ley á los setenta días de su presentacion, en cantidades mayores de cien pesos, conforme al contrato celebrado[text needed] con el comercio de este Míneral a dia 18 de Enero de 1890.

“Batopilas, Enero 28 de 1890. – Alex. R. Shepherd.”Diario de Hogar, Año IX, Núm. 134,18 February 1890. Given the timeframe these notes could have been produced locally, in Batopilas or Chihuahua.

On 1 February 1890 a group of local businessmen complained to the Secretaría de Hacienda about the legality of the latest issue of vales which were only payable seventy days after presentation in multiples of one hundred pesos. These referred to the meeting that Shepherd had called on 18 January 1890 but in fact only six merchants had attended and only two had given their consentDiario de Hogar, Año IX, Núm. 134, 18 February 1890. They also claimed that workers who received them in payment had to suffer a large discount when they tried to get money for themEl Minero Mexicano, 27 February 1890.

The Mexico City paper, El Diario de Hogar, on 18 February 1890, devoted its front page to an attack on this latest issue, pointing out that Shepherd, a foreigner, should not be treated differently to the native businesses in Yucatán that had just be massively fined for issues that actually predated the Codígo de ComercioDiario de Hogar, Año IX, Núm. 134,18 February 1890. The Secretaría initially imposed a fine of three hundred pesosDiario de Hogar, Año IX, Núm. 176, 8 April 1890. By April the Diario de Hogar had changed its tune. Although it applauded the fine of 300 pesos, it now praised Shepherd’ s entrepreneurship and the success of his company and argued that he had used his issue to keep workers employed when production flagged or for unprofitable but useful projects, and that to prohibit them would lead to the diminution of a thriving mining company, thousands of workers unemployed and the depopulation of the town. It called for the vales to be authorised, in the same way as banknotesDiario de Hogar, Año IX, Núm. 176, 8 April 1890.

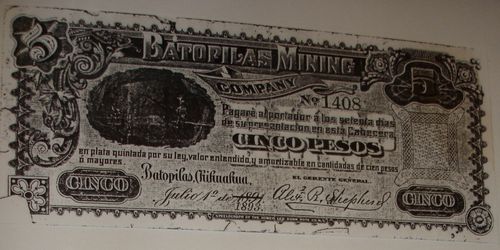

We also know of a $1 and a $5 note, printed by the Homer Lee Bank Note Company, again payable in silver seventy days after presentation, in quantities of one hundred pesos or more (‘al portador a los setenta días de su presentación en esta Cabecera en plata quintada por su ley, valor entendido y amortizable en cantidades de cien pesos ó mayores’ ), dated 1 July 1891. The $5 note is overprinted 1893, marking the start of a new fiscal year. Though these new notes were redeemable on the same terms as the 1890 notes, they appear to have been a different issue because (a) they do not refer to the contract with storekeepers and (b) surely El Diario de Hogar, in its description, would have remarked on the United States and Mexican shields on their reverse.

M621 $1 Batopilas Mining Company

M621 $1 Batopilas Mining Company

M622 $5 Batopilas Mining Company

M622 $5 Batopilas Mining Company

| date on note | to | from |

total |

total value |

||

| $1 | 1 July 1891 | |||||

| $5 | 1 July 1891 | |||||

| 1 July 1893 | includes number 1408 |

A December 1893 newspaper article tells of Shepherd’s ability to strong-arm (or bribe) even President Díaz and states that Shepherd’s notes circulated throughout northeast Mexico”Obstinacy and Diplomacy.

Gov. Shepherd is today in some ways one of the most obstinate men that ever lived, but it is a genial, good-natured obstinacy that really tickles the other fellow. Two examples will illustrate this: …

The next step was to introduce the use of paper money, but the banks at the capital placed every obstacle in the way. Then the doughty baron said: “I will print my own money and you must use it, for it will be secured by bullion placed in your banks.” This was declared to be an impossibility, an offense against the government punishable by death. “I can and I will, now you see,” said the petty king, and the money was issued. The miserly, silver-hoarding people kicked and said it was “muy malo,” “very bad,” “the rats eat it.” The king said “good for the rats,” and smiled and issued more money. The military commander threatened arrest, and the king said, “Come and take me if you think you can.” The governor of the state sent his peremptory orders by mail and by special courier, and was laughed at for his pains. The power of President Diaz was invoked, and his special messenger came and was a carefully entertained guest for several days and departed with his face wreathed with smiles, and it is said that he never stopped smiling and patting his pocket book, even when closeted with Diaz at the Castle of Chapultepec. Then the king received an invitation to visit the president, and the glasses of the two are said to have clinked merrily in the halls of Maximilian above the caves of Moctezuma. At all events the return trip of the king was that of a conqueror, every one from the private soldier to the minister of war bowing low before the dear friend of Diaz, and every one, from railroad porter to banker being paid of in the king’s new “shin plasters,” just so they could learn what it looked like. There has been no change in the Mexican laws, but today Shepherd’s greenbacks are current all over Chihuahua and all up and down the coast of the Gulf of California.” (The Evening Star, Washington, 14 December 1893) but Shepherd himself in the Batopilas Mining Company’s Annual Report for 1893 refers to Diaz' 'intelligent, liberal and progressive policy' and states that circulation was limited to Batopilas”Some publications have been made concerning myself and the currency of the company, which are so erroneous and extravagant as to require correction. There being no mint or bank of issue nearer than Chihuahua, President Diaz, with the intelligent, liberal and progressive policy which has always characterized his dealings towards properly conducted enterprises, granted me the right to issue vales payable in assayed silver, as a local currency. The total amount in circulation at this date, as shown by balance sheet, is $11,975.50, and has never exceeded $15,000. These are redeemed by drafts on Chihuahua, Mexico, or El Fuerte, and about two-thirds of them are redeemed weekly, none of them being circulated outside of Batopilas.” (The Boston Herald, 10 March 1894). THe truth was, no doubt, somewhere in between.

An article in a local Batopilas paper, in April 1894 stated that

in the mining centre in the sierra Saturdays and Sundays were the days that workers looked forward to, from the Monday when they go to work. On Saturday afternoon they settle their account with the Administrator with whom they work and receive the surplus of their wages, in not very clean but constant notes, which although they do not have the sonorous and Argentine tinkling of the provocative eagle pesos - which are already considered here as a numismatic curiosity, - nevertheless serve well to provide for their needs and encourage their vices. … The shops and clothing stores are full of buyers, and sales in each establishment are equivalent to and even exceed those of the rest of the week. The circulation [is] of Shepherd banknotes, and a few of the Banco Nacional, Banco Minero and Banco Mexicano, established in the capital of the State; It is remarkable that, with a little copper coin, … , [this] is all that serves for commercial traffic and transactions.

The classic country of silver, the breeding ground of this precious metal, … has no silver coin in circulation. Therefore, although this abnormal circumstance is exploited for large profits by some merchants; in general it constitutes an obstacle to commerce, an obstacle sometimes difficult to overcome, if not with a heavy penalty, especially when it comes to transactions with those who bring in consumer articles, and foodstuffs, from the neighbouring state of Sinaloa, where the Chihuahua notes are not in circulation. To overcome this difficulty, if it is not possible to obtain in silver or pesos fuertes in the market, one solicits from the Hacienda de San Miguel a draft on Mazatlán, El Fuerte or Álamos, issued at an established discountEl Minero, Año II, Núm. 19, 1 April 1984.

The practice of issuing its own currency ended at the government's request in the mid-90s, as the growth of the banking system began to ease the payroll situation for most of the mining camps. Shepherd then recalled his scrip and burned it at a public festival. In 1899 a correspondent reported that the Batopilas Mining Company had managed to see off all other retail competition. The company paid half in cash (numerario) every fortnight and half in goods (efectos) through an account at the tiendas de raya, and even though the tiendas’ prices were 40-50% higher than others, this stranglehold had defeated the competitionEl Continente Americano, 19 July 1899. The system was still in place in 1901 with the company paying every three or four weeks, half in cash and half in goods from the tienda de raya, which always lacked basic necessities (Regeneración, Tomo II, Núm. 57, 7 October 1901).

Various references confirm the currency's semi-official status. In November 1886 a Mexico City newspaper reported that on the northern frontier a bushel of maize would cost $2.50 in Batopilas notes (papel del Banco de Batopilas) as compared with $2 in Banco de Santa Eulalia notes, $1.80 in Banco Chihuahuense notes and $1.20 in American dollarsEl Diario del Hogar, 5 November 1886 while three months later they were quoted, as ‘papel del Banco Shepherd Batopilas’ at 59-60c, the same rate as the Banco de Santa Eulalia and Banco Mexicano but less than the Banco Minero Chihuahuense and Banco Nacional de MéxicoPeriódico Oficial, 9 February 1887. The Ciudad Chihuahua newspaper El Norte, in its panegyric on the Banco Minero, mentioned an earlier Bank of BatopilasEl Norte, 5 July 1900.

Mendoza y Abasolo, Sucs

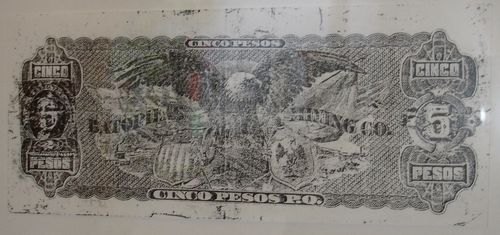

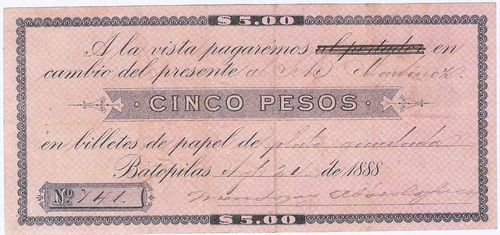

M613 $5 Mendoza y Abasolo, Sucs.

M613 $5 Mendoza y Abasolo, Sucs.

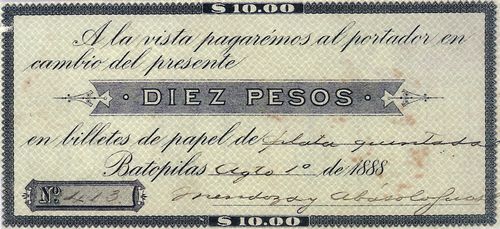

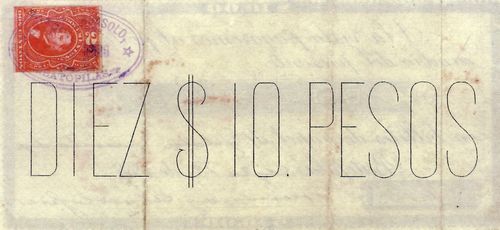

M615 $10 Mendoza y Abasolo, Sucs.

M615 $10 Mendoza y Abasolo, Sucs.

| date on note | from | to | total number |

total value |

||

| $5 | 24 August 1888 | includes number 741 | ||||

| $10 | 1 August 1888 | includes number 413 |

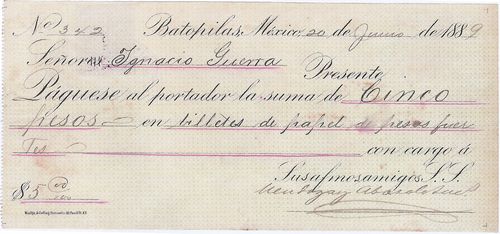

The company of Mendoza y Abasolo, Sucs., Batopilas must have been the successor or associate company of Mendoza y Nesbitt, which issued tokens in Barranca de Cobre and UriqueMartin J. Nesbitt was a mechanical and mining engineer. In 1905 he was part of the firm of Becerra y Nesbitt, wholesalers, forwarders and property agents (Herald, 15 November 1905). Becerra was Buenaventura Becerra. Martin married Buenaventura’s daughter, took over charge of the mines when he died and later succeeded him as jefe político of Urique. One five pesos note of this company ‘in paper notes backed by hard cash/silver pesos (en billetes de papel de pesos fuertes)’ is dated 24 August 1888. A ten pesos note, dated 1 August 1888, is payable in paper notes backed by assayed silver (en billetes de papel de plata quintada).

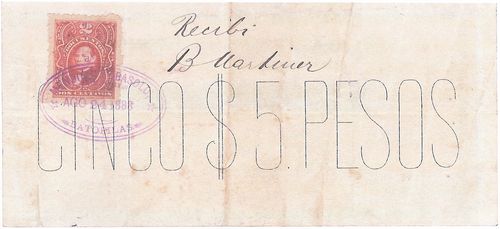

M614 $5 Mendoza y Abasolo, Sucs.

M614 $5 Mendoza y Abasolo, Sucs.

We know of a similar bearer cheque for five pesos, dated 20 June 1889.

In August 1892 the company’s premises in Batopilas were destroyed by fire at an estimated loss of $25,000Diario del Hogar, 13 August 1892: El Nacional, 13 August 1892.

Again, these notes had a short lifespan. On 13 April 1893 Mendoza y Abasolo, Sucs. asked the Banco Minero for a consignment of $10,000 in its notes, guaranteed by Alexander R. Shepherd. The bank sent $7,000AGN, Antiguos Bancos, Actas de Banco Minero, libro 1, 28 February 1888 to 5 January 1899.

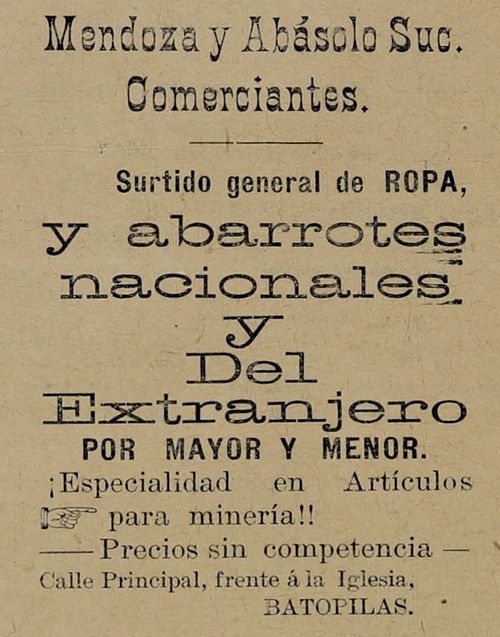

Advert for Mendoza y Abásolo Suc. from El Minero, Año I, Núm. 6, 17 December 1893

Mendoza y Abásolo Suc. advertised in the weekly local paper, El Minero, as a business with a general stock of clothes and national and international groceries, both for wholesale or for retail.

In January 1894 the business announced that it was suspending payments because its member, Juan H. Mendoza, had gone to Europe and was not going to return. However, the majority of its creditors (the Banco Mexicano, Banco Minero, Ketelsen y Degetau and the Banco Nacional de México) expressed their confidence in Benito Martínez who was to remain in charge of the assets of the dissolved firmEl Minero, Año II, Núm. 10, 14 January 1984: La Patria, 25 January 1894: Semana Mercantil, 25 January 1894. However, Mendoza later returned to Batopilas because in November 1896 it was reported that certain mining companies, including Mendoza, were abusing their workers by paying half in money and half in goods (efectos)La Patria, 26 November 1896. Note that the newspaper did not see fit to mention Shepherd’s company. Mendoza went on to mine in Baja California.

La Hacienda Nueva Australia

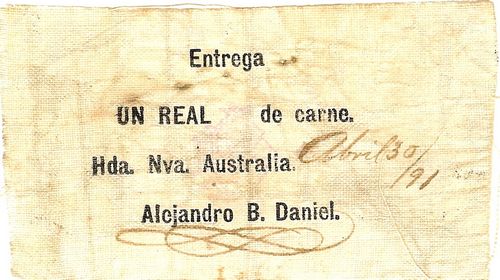

M624 1r Hacienda Nueva Australia

M624 1r Hacienda Nueva Australia

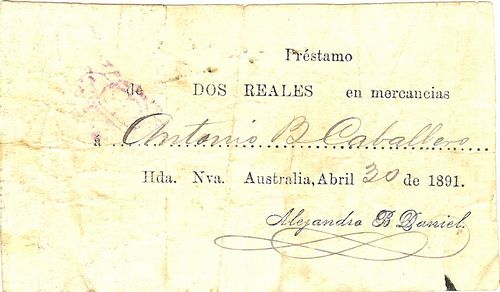

M625 2r Hacienda Nueva Australia

M625 2r Hacienda Nueva Australia

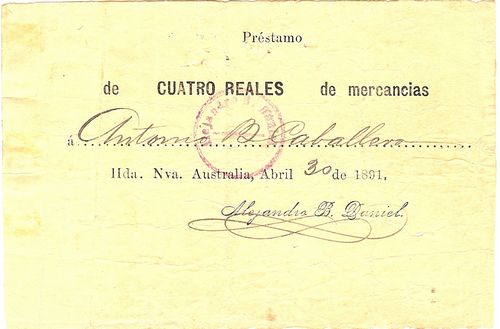

M626 4r Hacienda Nueva Australia

M626 4r Hacienda Nueva Australia

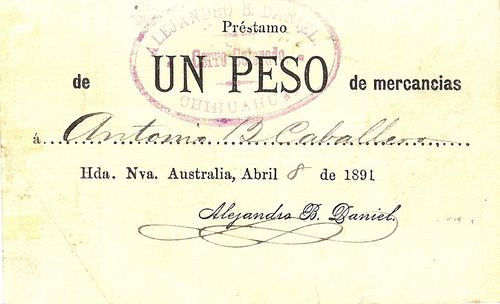

M627 $1 Hacienda Nueva Australia

M627 $1 Hacienda Nueva Australia

The ruins of La Hacienda Nueva Australia are still visible at Cerro Colorado, three miles upstream of Batopilas. The Becerra brothers discovered gold there in 1887 and by 1889 with other shareholders had established a large mining establishment (hacienda de beneficio)El Estado de Chihuahua, 23 March 1889. This hacienda issued vouchers for meat (carne) or merchandise (mercancias). The surviving notes have the signature of Alejandro B. Daniel and are dated 8 April and 30 April 1891. The two reales voucher was printed on cloth, whilst the three others (one real, four reales and one peso) were on paper.

|

Alejandro B. Daniel, a Mexican, was born in 1863. He still owned the Nueva Australia in 1916 and was also co-owner of the Compañía Minera de Cuauhtémoc y Anexas. |

Santo Domingo Silver Mining Company

Although no notes are currently known, mention should be made of this company. The Big Creek Mining Company was initiated in 1867 with its mines located in Batopilas and its corporate offices in Philadelphia, PennsylvaniaJohn P. Logan was the president of the Big Creek Mining Company and E.L. Stillson was the superintendent of the Batopilas mines. The company officially changed its named to the Santo Domingo Silver Mining Company in 1871. Its papers are held by the Historical Society of Pennsylvaniawww.hsp.org: Collection 3034 and include a payroll book (1897-1898) and a set of payroll notes and various bills (1891-1898, n.d.). The payroll book has a separate page for each pay week with entries that list the employee's occupation (i.e. washer, watchman, peon, breaking metal, cook, etc.), name, and amount paid for each day, as well as for the week in total. Some men worked up to seven days a week and wages ranged from $1 to $2.50 a day. Approximately fifteen men are consistently documented each week. Each page is stamped at the top with "Admin. subalterna del timbre, Batopilas." The payroll book pages also itemize each week's expenses for supplies such as hay, wood, and grocery bills. There are also many small sheets of paper with notes concerning payroll.