Bouligny and Schmidt, Sucesores

Bouligny and Schmidt was one of the major printers in Mexico City.

Edgar Bouligny, born in New Orleans in 1852, came from an established French Creole family. His father, John Bouligny, represented Louisiana in Congress in the years immediately prior to the Civil War and as an independent, stubborn, and virulently unionist member, he received national attention for bravely refusing to vacate his seat when Louisiana voted to secede, being the only Congressman from the South to remain.

In 1885 Edgar Bouligny was listed as working in Nichol’s Publishing House in Mexico CityThe Two Republics, 5 July 1885. Then he had his own printing company, which he sold in June 1888. He left for the United States, but it was reported that he would soon return as the agent of a large American lithography establishment The Two Republics, 1 June 1888. This became Bouligny & Co., a subsidiary of a Philadelphia firm. It was a printer’s and book-binder’s, located at calle de los Rebeldes núm. 1. Among other jobs it printed lottery tickets and other valuables, including it seems vouchers for companies such as the Negociación Minera de San Andres de la Sierra.

Bouligny had a violent temper and a tendency to resort to firearms, which had already led to several deathsA sensational newspaper article recalled: “The strain of fiery Gallic blood coursing through his veins, backed by a spirit of reckless daring, made him truly formidable as a fighter, and it is said he was a stranger to fear. An insult which other men would barely notice was sufficient to arouse his anger and bring about either a fight on the moment, or a duel soon afterward. And he seldom missed in his aim when facing an adversary in mortal combat. "Fighting duels to wipe out insults," he once said in New Orleans, with a careless laugh and a languid grimace, "is the same to me as eating." He was polite and punctilious in his duels as any French grandee, and invariably took such affairs with singular coolness and seriousness. On these occasions his quick temper was wholly lost sight of, and his seconds wondered at the young man's bravery. All preparations made, at the given signal he would turn about as on a pivot and fire almost while turning. His man was dead, probably without having pulled the trigger.

Bouligny entered into the affairs of the reconstruction period in his native city with that interest and earnestness which were characteristic of his every action, and which led some persons to think that he was too meddlesome. A quarrel arose over some question of these affairs. A duel was fought and Bouligny’s opponent killed. The matter took place in the outskirts of New Orleans. Considerable talk was caused by his first killing, which brought him before the people in an unpleasant light. A friend of the dead man had a grievance against Bouligny and stated in the hearing of one of the latter's friends, "I'll shoot that - - Bouligny on sight." The young man thus threatened was told to be on his guard, and particularly one night at the New Orleans Opera House, as the other man was determined to carry his threat into execution before the sun should rise.

Again Bouligny was warned. He was sitting in the theater with his young wife when told that his enemy was waiting in the street, but coolly sat out the play and walked out without the least concern, his wife leaning on his arm.

"Are you Edward Bouligny?" asked the man who had threatened him outside the theater door.

“Yes," was the reply, accompanied by profanity and a bullet, the latter from beneath Mrs. Bouligny's opera wrap, which served as a shield for the revolver. That was the second victim of his pistol.

His third was a Federal officer, who fell in a fight at the New Orleans Jail while Bouligny and a mob were attempting to take a prisoner — a friend — from the jail. In this affray eighteen men were killed by the Gatling gun. Bouligny escaped the shower of deadly lead. The gun dropped too low at first sight and the discharge blew a hole through his leg below the knee. He fell and a moment later the leaden hail hissed above him, cutting down the mob around his prostrate figure.

The next time he sent his fellowmen into eternity was during the police suppression of the lawless La Mafia in New Orleans, an organized gang of Italian highbinders. He assisted the police materially, for which he earned the enmity of La Mafia.

Bouligny was almost blind without powerful magnifying-glasses, a fact which some of the Mafia gang were aware of. So when they decided to take his life boldly on the streets of the city one of these ruffians walked beside him and tore off his spectacles. Quick as a flash Bouligny's pistol was out, and in an instant the fellow who took his spectacles was dead before him. Then followed a fusillade of pistol bullets from the group of eight or ten Mafia across the street, whizzing around the helpless man's head and tearing away his clothing. Nothing terrified, he fell upon his face and groped about him on the ground for his glasses, while the shooting was kept up with relentless zeal. He found the spectacles, adjusted them; and stood up to meet his would-be assassins.

Every time he fired a man fell, and being prepared for such an assault he continued firing until either five or six of his assailants were dying or dead upon the street. The others decamped, some badly wounded.

A negro robbed a friend of Bouligny in El Paso, Texas, and tried the same business with Bouligny. who killed him on the spot.

In Arizona a man covered him with his revolver, and Bouligny agreeably admitted that his new acquaintance could "wipe the earth" with him, at the same time bowing politely with hands raised. The bowing became obsequious and accompanied by sweeping gyrations of Bouligny's body, to the complete delight of the man with the revolver.

But suddenly Bouligny managed to twist his body and quickly draw his pistol, firing at once. Again he killed his man.

There are three or four other such cases which could not be remembered yesterday by the narrator, in which Bouligny took human lives. Withal he was not a bad-natured man nor a desperado. He was thrown among people who freely used their pistols, and all his murders were in redeemable encounters or free and open fights. He has a charmed life, but what may become of him now under Mexican law, which does recognize capital punishment, is a matter of conjecture” (San Francisco Call, Volume 67, Number 165, 12 November 1890).

This account sensationalises the Opera House shooting. Another account says "As a young teen, [he] was once arrested for firing his pistol into the belly of another teen who first punched him on the steps of the French Quarter’s elegant Opera House at the conclusion of a performance there. After firing the gun, he fled into the building through the scattering crowd, ran up the staircase, and somehow avoided three shots fired at him by his accoster who chased after him. (One cannot help but wonder why two teenagers from upstanding families were carrying weapons). Both boys were arraigned in court the following day wherein a high-pitched argument erupted between them in front of the judge’s bench. After being subdued, they were both sentenced to 24 hours in jail and fined $25." It certainly whitewashes the killing of the African-American. In fact, while staying at the Vendome Hotel, El Paso, on 5 May 1887, Bouligny sent for a barber, Ned Kennard, to go to the hotel and shave a sick friend. Kennard did so and charged $1 for the job. Bouligny refused to pay what he considered an exorbitant charge. Kennard picked up a rock, when the latter raised his pistol and fired, The ball struck Kennard in the neck killing him almost instantly (Los Angeles Herald, Volume 27, Number 31, 6 May 1887). On the evening of Saturday, 8 November 1890, two workers of his printing house, Gabino Lara and Rafael Insunza, who had been paid off earlier in the day, returned to complain that he had not been paid in full. When Bouligny refused them, they went in search of a policeman who accompanied them back to the shop. The two went inside but the policeman, Gabriel Cortés, stayed outside until he heard an argument. He then entered and got into an argument with Bouligny himself. Bouligny drew his pistol and shot, Cortés responded and several shots were fired. Alfred W. Lobenhoffer, the firm’s book-keeper, tried to close a door between the two parties to end the affair, and received a bullet in his spine. Bouligny fled but surrendered to the police in the company of his attorney later that night El Siglo Diez y Nueve, 10 November 1890; La Vanguardia, 11 November 1890. The English language The Two Republics, 11 November 1890, gives a more jaundiced report, favourable to Bouligny.

Lobenhoffer held on for 18½ days before dying, whereupon an autopsy established that it was a bullet from Bouligny’s pistol that killed himThe Two Republics, 25 November 1890. On 12 April 1891, after a trial, Bouligny was sentenced to four years' imprisonment and one year's detentionThe Two Republics, 12 April 1891; San Francisco Call, Volume 69, Number 134, 13 April 1891. However, on 18 December 1891 he was aquited on appeal and set freeDaily Anglo-American, 19 December 1891.

In May 1892 it was reported that Bouligny, along with some well-known investors, was organising a new company, to be called “The Mexican National Bank Note Company” to undertake printing, but more especially, “engraving of the finest character”Daily Anglo-American, 16 May 1892. The shareholding was $50,000 and among the investors were Sebastían Camacho, José Gargollo, Pedro Mendez, León Signoret, R. Arozarena, Eduardo Dublan, Samuel Knight and Fischweiler. However, nothing seems to have come of this.

In January 1896 Carlos Schmidt, a German, joined the firm, which was then called Bouligny & Schmidt, S. en C.The Two Republics, 11 January 1896. Bouligny died in New Orleans on 12 April 1901 after a long illnessThe Mexican Herald, 13 April 1901. Strangely, his son, Edgar Jean Bouligny, Jr., continued his father’s irascible behaviour, becoming the first American to be wounded in World War I“At 13 [Edgar Bouligny, Jr.] found himself in a New Orleans boarding school for boys where military science was taught, the College of the Infant Jesus, presumably for disciplinary reasons. Even within this closed environment, however, he managed to burglarize over 20 homes and businesses. His parents took their lawyer’s advice and had him plead insanity. The strategy worked. He was sent to the Louisiana state mental hospital in Jackson, avoiding detention, at least in a penal facility.

Not long thereafter, he escaped, fled to St. Louis at 17, and took a job as a bellhop at a hotel in that city. A short time later his wanderlust brought him to San Francisco where he was shanghaied and forced to work as a deckhand on a steamer to China, then back to San Francisco. Disillusioned and aimless, he joined the U.S. Army and, in his first assignment, helped to guard that city from looters in the aftermath of the earthquake of 1906. He left the Army in 1912, but when war broke out in Europe in 1914, he felt drawn to the adventure. Edgar’s affinity for France and his sympathy for their struggle against the Germans was compelling. Besides, he was fluent in French, thanks to his mother’s’ insistence on a proper Creole education for her son. He along with roughly 120 other Americans joined the French Foreign Legion.

Bouligny enlisted in August of 1914 in the Legion, one of the first Americans to do so, and remained there until May of 1917 when he became a fighter pilot for the notorious Lafayette Escadrille. During his stint on active duty, he was wounded four times at the Battle of the Somme, becoming the first American casualty of the Great War. More danger befell him when an enemy bomb exploded under his trench near Rheims. Bouligny was buried in the debris for 27 hours before he was accidentally discovered and dug up, stunned but still alive. Later as a pilot he survived landing his disabled biplane after taking fire from the famed German “Flying Circus” in the skies over Albania. Arrogant as ever, the six-footer often boasted that the Germans did not have a bullet with his name on it. He was awarded the Croix de Guerre by the French military for his heroism in combat.

Before returning to the U.S., he met a pretty French girl named Odile Hubeau while having photos developed at the shop in Paris where she worked. They immediately began seeing each other several times a week. Deeply in love, they were married nine months later. But what appeared to be an endearing story of a wartime romance abruptly turned sour when, a day after their marriage, Edgar confessed to her that he was already married to an American. To the lovesick young French woman, that seemed not to be an impediment as long as her hero divorced his first wife, which he did once they arrived in the U.S. to begin their lives together. There, they would drive around the nation as partners in a photography business, an affinity shared by both of them. But what followed was only occasional success selling their work to travel magazines and such.

By the late 1920s they were broke, so the couple decided reluctantly to return to New Orleans, perhaps to lean on Edgar’s family for financial help. They rented a cheap French Quarter apartment at 409 Bourbon Street. Penniless and without direction, the decorated airman was no longer held in the esteem he had once achieved while in uniform. His wartime exploits overseas never translated into a solid post-war career in America, and the discontent stirred his inner demons. Clinging to the memories of his salad days as a pilot in France, Edgar found solace sharing the aerial photos he took from his cockpit while flying over the ruins of shelled cities and broken battlefields to American Legion posts and civic associations. During these presentations, Edgar could at least temporarily relive those moments which connected him spiritually to his great great-grandfather Dominique, whose burial in St. Louis Cathedral among Louisiana governors and bishops attested to the significance of his life.

But these talks were never sufficient to tame his tortured spirit. He began going out alone at night to various clubs in the “Tango Belt,” a niche in the French Quarter on upper Iberville Street where the lascivious dance continued well into the early morning. Edgar returned home way too late, way too often. Not surprisingly, this led to loud arguments with Odile, followed by curses and beatings. By 1931 the marriage was irreconcilable. The 43 year-old Bouligny was exhibiting the classic symptoms of what was then called “shell shock” or, in modern terminology, PTSD. He had become only a residue of his former self, an ugly predator, and his still adoring wife was his convenient and easy prey.

One day he seemed particularly agitated and punched her, knocking the petite 37 year old to the floor of their tiny kitchen. When the six-footer came at her again with clenched fists, she shot him with his own .22 caliber pistol, which she had hidden in the kitchen sideboard. As he lay dying, she picked up the head of her bleeding husband and rested it on her lap crying over him, sobbing again and again that she loved him. Odile was taken to the police station where she detailed in both French and fractured English the recent years of physical abuse. The coroner identified eight bruises on her which, he said, were likely caused by kicks or punches, validating her claim of self-defense. Several of the couple’s relatives hurried to the police station to speak on her behalf, including Edgar’s inconsolable 76 year old mother who prayed the rosary incessantly throughout the ordeal. “Poor boy. He was never the same after the war,” she cried. “He was sick. None of my family feel hard against her.” Odile was released without charges, still muttering, “I love him still. I will always love him.”

Newspapers from Modesto to St. Louis to Brownsville gave the story front page status. In a few, the report occupied an entire page accompanied by broad artist renditions of the murder scene and photos of the couple – Edgar, square jawed and looking resolute in his impeccable uniform and Odile, prim in the stylish dress of the 1920s. Several reprinted an entire account of Bouligny’s adventures before and during the war written by Captain Paul Rockwell, who had earlier penned a history of Americans who joined the French Foreign Legion before the U.S. declaration of war. The former pilot had longed for the attention he had once received as an acclaimed fighter ace over a decade before, yet as Odile made her way back to her native country shortly after the shooting, that attention was now fraught with disdain for him rather than veneration. Once a national hero, the New Orleanian had become merely a character in a tragic opera.”

(taken from Brian Altobello, “World War I Centennial”, in www.myNewOrleans.com).

Thereafter, the company was Bouligny & Schmidt, SucesoresIn 1903 its staff included Henry Sitges as manager, Donald and Edwin Murray and Charles Naylor as engravers, and Guillermo Brugmann as bookprinter (The Massey-Gilbert Blue Book of Mexico, 1903).

The firm became involved in printing paper currency in 1914 when the banks were desperate for new notes. As Charles Blackmore, the ABNC's Resident Agent in Mexico City, explained on 4 May in a letter about the Banco de Guanajuato, the “notes called for in this bank's last order are to be paid to the Mexican government on account of the loan which has been made on all the banks of the Republic. As it is impossible to receive any shipments of notes from New York on account of the present unsettled conditions the government has given instructions to the banks that they are to have their notes printed here in Mexico, replacing the notes which are printed here by the notes which they receive later on from New York"ABNC, folder 237, Banco de Guanajuato (1907-1932).

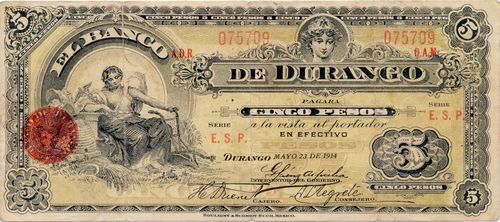

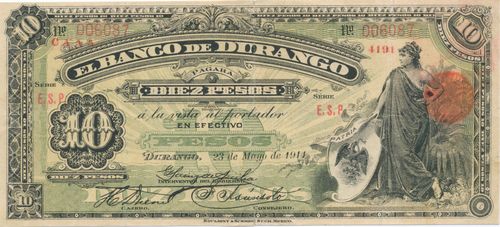

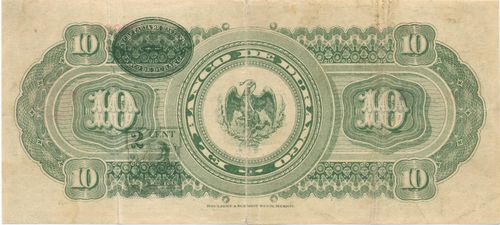

Bouligny and Schmidt used the same templates for a series of $5 and $10 for the Banco Minero de Chihuahua, Banco de Coahuila ($10 only), Banco de Durango and Banco de Guanajuato. The Banco de Durango had only recently received 25,000 $10 notes from the ABNC in March 1914, which demonstrates how quickly the need for banknotes grew.

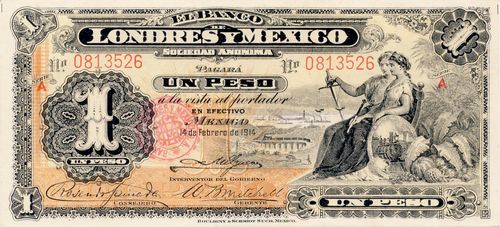

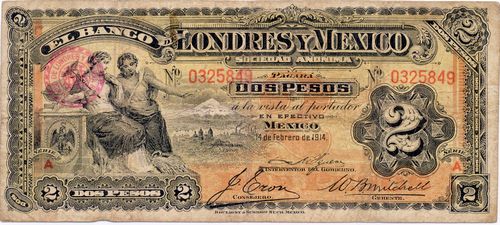

They also produced quite reasonable $1 and $2 notes for the Banco de Londres y México.

The company also produced notes for companies in Acapulco, Guerrero, Misantla and El Higo, Veracruz and for mining companies in Pachuca, Hidalgo (the Real del Monte y Pachuca, La Blanca y anexas and Purisima) and at El Oro, Estado de México.