Victoriano Huerta' 1915 abortive issue

Huerta and Abraham Z. Ratner

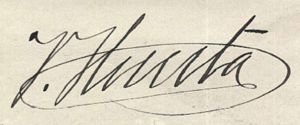

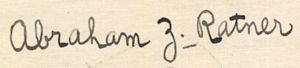

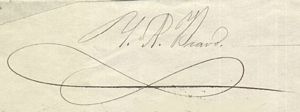

When Victoriano Huerta was forced from the presidency in July 1914 he went into exile, in Britain, then Spain, and arrived in the United States in April 1915. In May the American Bank Note Company had received a personal introduction to Abraham Z. Ratner, a wealthy newspaper owner who was Huerta’s financial adviser and private secretary. The ABNC wrote to Ratner with a quotation for 1,832,500 notes (later reduced to 750,000) in seven denominations and agreed to have the engravings finished and ready for approval by 30 June. However, it added a stipulation that no delivery would be made to Ratner until “Gen. Huerta is on Mexican soil and is recognized as President of Mexico by such portion of the Mexican Congress as are on Mexican soil”. On 4 June the ABNC received copies of the three signatures for the notes – Huerta as Presidente Interino, Ratner as Secretario de Hacienda (later amended to Agente Financiero (possibly because he was not a Mexican)), and General I. A. Bravo as Secretario de la Guerra.

|

Huerta pledged allegiance to President Madero, and carried out Madero's orders to crush revolts by rebel generals such as Pascual Orozco, defeating him at Rellano in May 1912. However, in February 1913 Huerta joined a conspiracy against Madero, who entrusted him to control a revolt in Mexico City. The decena trágica saw the forced resignation of Madero and his vice president and their murders. The coup was backed by the United States under the Taft Administration but the succeeding Wilson administration refused to recognize the new regime and allowed arms sales to rebel forces. The Constitutionalists defeated the Federal Army and Huerta was forced to resign on 15 July 1914 and flee the country to Spain, only 17 months into his presidency. While attempting to intrigue in the U. S. against the Carrancista government, Huerta was arrested in 1915 and died in U.S. custody. |

|

Abraham Z. Ratner was a controversial figure of Jewish origin, born in Lithuania in 1877. He settled in Tampico, Tamaulipas between 1895 and 1898 and opened the Tampico News Company in 1902, offering a mail order service of imported goods to 70,000 customers throughout Mexico. Ratner and his brother, José B. Ratner, moved their business from Tampico in 1909El Imparcial, 18 January 1910, and branched out on a larger scale in Mexico City, occupying one whole building on Calle Palma and a salesroom on Avenida 16 de Septiembre. While the industries of Mexico were going at normal speed the mail order business thrived. Fifty young women were employed as typists to attend to the correspondence, and dozens of clerks and employees were required for the details of the business. Toward the close of 1910 the beginning of the Madero revolution curtailed the volume of sales. In the spring of 1911 the business was still further depressed, and the Tampico News Company found itself deeply in debt to the Mexico City Banking Company. But the Ratners had secured an enormous stock of American firearms— rifles, carbines, revolvers, automatics, with abundance of ammunition—picked up at bargain prices in the StatesThe Mexican Herald, 10 August 1911. Shortly after it was received in Mexico City the de la Barra Government issued an edict under which consignments of arms to dealers were held in the custom houses. Dealers were permitted to sell the stock on hand but could not replenish it. The Ratners had already brought in their great supply and now they had a clear field with monopoly prices. They advertised widely and their profits were large. With the increase of reported and actual disturbances throughout Mexico, in the months following Madero's inauguration, the firearms sales of the Tampico News Company grew steadily. In February 1912, the Madero Government became suspicious, and caused two secret service men to solicit and secure positions in the Ratners' employ. On the night of 2 May their efforts one of them was chosen as an aid to the Ratners in a delivery of arms. After midnight an automobile was brought into an alley alongside the Tampico News Company building on Calle Palma, the arms were placed on board and were conveyed out of the city beyond Tacubaya where the car was met by Emiliano Zapata and a body of his followers. The detective made his report immediately upon his return and at daybreak the Ratners were taken into custody, and their remaining stock was confiscated. That day they were deported to New York as “pernicious foreigners" under article 33 of the Mexican ConstitutionThe Mexican Herald, 15 May 1912. After Madero was killed, the Ratners returned to Mexico, and resumed business and in October 1913 the Tampico News Company moved to sumptuous new offices on the corner of Avenida 16 de Septiembre and Avenida BolivarMulticolor, 16 October 1913. In December 1913 when people began to refuse to accept state banknotes, Ratner, in a gesture of confidence, announced that his Tampico News Company would accept all such notes, even those of states, like Durango, that were in the hands of rebelsEl Independiente, 20 December 1913. Ratner acted as President Huerta's financial advisor and personal friend and in 1913 helped him buy a shipment of weapons in New York, which would enter Mexico as contraband to fight the Constitutionalists. In February 1914 he left Mexico, heading to New York and EuropeEl Diario, 18 February 1914: The Mexican Herald, 20 February 1914 but was back to Mexico to give financial support to the Spanish driven out of Torreón and to oppose the American invasion of VeracruzEl Pais, 22 April 1914. In April 1915, together with generals Aurelio Blanquet and José C. Delgado, he accompanied Huerta from Spain to New YorkThe Mexican Herald, 12 May 1915. By this time the newspapers had forgotten his philanthropy and avowed Mexican identity and referred to him as a serial arms dealer and JewEl Pueblo, 21 May 1915. He died in 1919. |

|

|

In October 1899, accompanied by his staff, the 1st and 28th Battalions and a squadron of cavalry, Bravo landed in Progreso, Yucatán, in order to pacify Yucatán and end the fifty year War of the Castes. Seven months later, on 4 May 1901 he declared a successful end to the war and in 1903 became the Jefe Político of the new territory of Quintana Roo. He then returned to Mexico City, where he received the military command and the command of the Army Corps of the Federal District. When Madero became president he was discharged from the army but during Huerta’s dictatorship he was recalled and placed in command of the Nazas Division. During the siege of Torreón, which lasted 14 days, he was relieved and went on to take the military command of the Federal District. After the departure of Huerta and the change of government, Bravo, like many other military and executives of past governments, went into exile in Texas, where he died on 11 April 1918. On 3 May 2021, the Mexican state offered an apology to Mayans and Yaquis "for the xenophobic and genocidal measures" taken during the War of the Castes. It is reckoned that 250,000 died during the war. |

|

and on 11 June ordered its works to prepare the platesABNC.

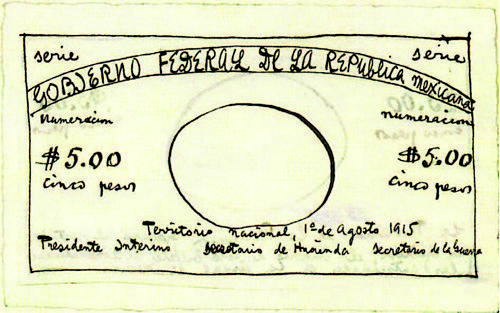

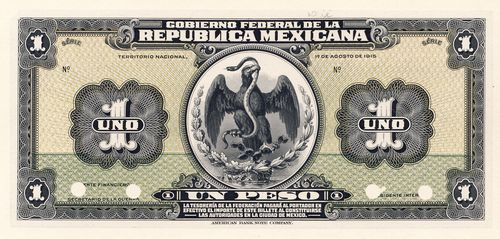

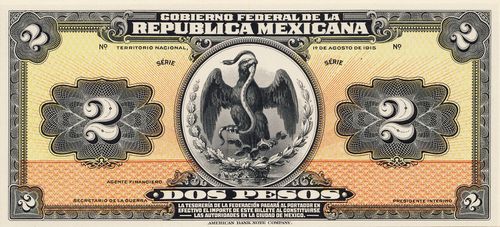

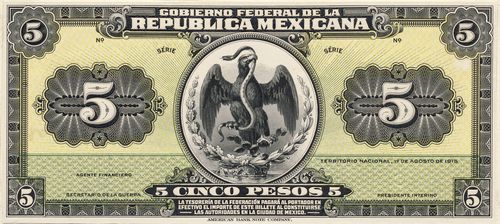

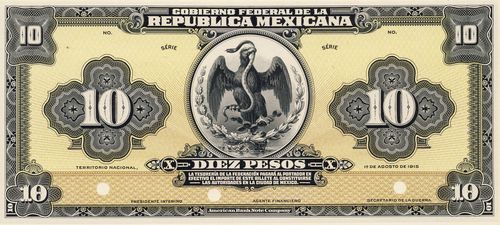

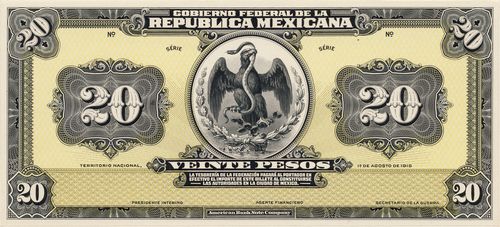

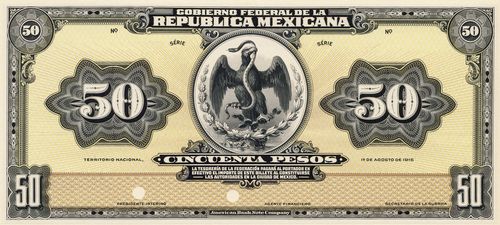

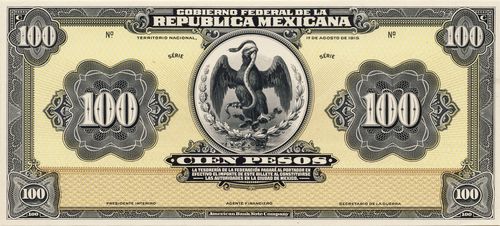

The mock-up shows that these ‘Gobierno Federal de la República Mexicana’ notes were to be dated 1 August 1915, on Mexican soil. The ABNC produced some proofs: note the uncommon titles of the proposed signatories (PRESIDENTE INTERINO, AGENTE FINANCIERO and SECRETARIO DE LA GUERRA), the dateline (TERRITORIO NACIONAL, 1o DE AGOSTO DE 1915) and the condition that the notes would be redeemed once the Tesorería de la Federación had been established in Mexico City.

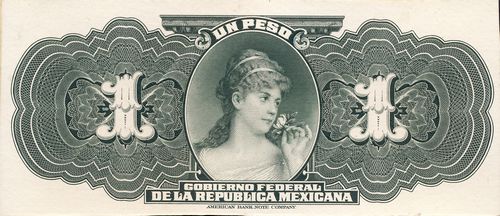

All that remains of this issue are black and white face proofs and multi-colored face and back proofs of six denominations: one, two, five, ten, twenty, fifty and one hundred pesos.

M1267a $1 Gobierno Federal

M1267a $1 Gobierno Federal

M1268a $2 Gobierno Federal

M1268a $2 Gobierno Federal

M1269a $5 Gobierno Federal

M1269a $5 Gobierno Federal

M1270a $10 Gobierno Federal

M1270a $10 Gobierno Federal

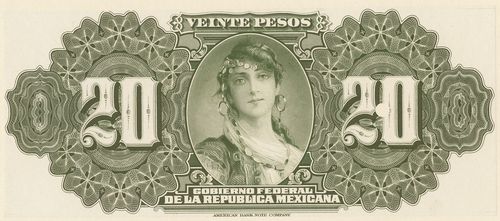

M1271a $20 Gobierno Federal

M1271a $20 Gobierno Federal

M1272a $50 Gobierno Federal

M1272a $50 Gobierno Federal

M1273a $100 Gobierno Federal

M1273a $100 Gobierno Federal

The stock vignettes of females on the back were C-586 for the $1 note, C-396 $2, C-1292 $5, C-537 $10, C1301 $20, and C-547 $50. The $20 note includes the first appearance of a vignette (‘Ideal head of an Algerian Girl”) that was later, in 1925, used for the early $5 Banco de México notes and led to the legend that it was a portrait of Gloria Faure, Alberto J. Pani’s mistressGloria and her sister, Laura, originally from Catalonia, Spain, were dancers and actresses who acted in reviews, as well as being “friends” of prominent politicians, including the then Minister of Finance Alberto J. Pani. When Pani went to New York in 1925 to re-negotiate the Lamont - De la Huerta debt agreement with the Americans on behalf of the Mexican Government, Gloria accompanied him. Pani’s extramarital activities then became a political issue in Mexico when opponents used them to attack the administration of President Plutarco Elias Calles. They hired a private detective to shadow the finance minister and the reports of his comings and goings with Gloria Faure were leaked to the newspapers. The front page of the 14 October edition of the New York Daily Mirror, a Hearst tabloid, featured a photograph of Faure, posed with a dress provocatively raised above her knees. An article on page 3 was headlined “Beauty Calls Pani Mexico’s “Best Lover” But Gloria Hates Him Now Because He Sent Her Home. Consul Speeds Girl to Border as Government Refuses Action in Case” and explained

“The governments of two nations, of two states and of a great city united yesterday in hustling one demure, if ravishingly beautiful little 19-year-old Mexican senorita out of New York.

Early last evening Senorita Gloria Yuste, also known as Gloria Faure, Mexico City actress, was speeding toward home under the special protection and at the expense of the Mexican Consul General here, a half-brother of President Calles, over a road expressly for her by the State Department of the United States.

She left behind her a chaos that shouts of international complications, Mexican revolutionary stirrings, the plots and counter-plots of Latin American intrigue, AND—

In an upper room of the Waldorf-Astoria, she left a distraught Mexican Secretary of Finance Senor Alberto J. Pani, sadly embarrassed by the petition brought by political enemies here before our Department of Labor, demanding action against him under immigration laws and the Mann White Slave act for allegedly having brought the senorita from Mexico to the Waldorf-Astoria for immoral purposes.

…

Early yesterday morning in a huge touring car, one of eight maintained by the Mexican consul general’s office, she was bundled over to Elizabeth, N. J. and there, while wires between Elizabeth and New York, and New York and Washington, were humming over the solution of the dilemma she has caused, Senorita Faure sat in a room of the Hotel Whittmann in Union Square, tapping the ashes from a perfumed and monogrammed cigarette and smiling through languorous half-closed eyes, said to a Daily Mirror reporter in liquid Castilian. “I loved Senor Pani very much. He was a wonderful lover, the most wonderful by far in all of Mexico.”

The languor dropped and black eyes flashed fire.

“But now I hate him. Why should he drive me out of New York in the middle of the night?”

Later, calmed, she added: “Of course, I knew he was married, but his wife never understood him,” and the reporter wondered if she had any thought that as a flapper-philosopher on the subject of running away with other women’s husbands she also thought she was being original.

“My Senor Alberto is as wonderful a lover as he is a financier. You do not realize how he can love, how he made shivers go up and down me when he touched his lips with mine. “Go back to him? Never! My lover must love only me, and me always. I can be cast aside but once.”

Senorita Faure declaring through an interpreter on leaving: “Do not think bad of me. I am just like any New York girl.”

Though nothing developed in the United States, Pani was bitterly attacked in the Mexican Chamber of Deputies, though defended by Calles who told his Deputies that he did not want a Cabinet of eunuchs.

When the $5 note was issued earlier in 1925 it was rumoured that the gitana (gypsy) was in fact a portrait of Gloria Faure. The story was widely believed, encouraged by Gloria herself who kept a photograph of herself in gypsy costume to show visitors. Even when she retired to the Cote d’Azur her house, and the photograph, was an obligatory stop for Mexican tourists.

However, the story was always a myth. In September 1925 the Banco de México had written to the American Bank Note Company enquiring about the origin of the vignette, which suggests both a lack of discipline in their commissioning processes and, perhaps, fears about the rumours that were circulating. The ABNC made enquiries and replied that the vignette was a stock image, engraved on 27 September 1910 by their engraver Robert Savage from a book of lithographs that the company’s then president, Mr. Green, had picked up on a trip to Europe. The lithograph depicted an Algerian girl and the vignette was entitled “Ideal Head of an Algerian Girl”.

However, this knowledge was lost, so in 1976 Profesora Guadelupe Monroy, who was setting up the bank’s numismatic museum, wrote again to the ABNC asking for details on the portrait. The reply repeated that the original engraving had been made in 1910 and was of an Algerian girl.

So the myth was once again debunked, as it has been since, though the legend still lives on in many dealers’ lists and catalogues. But questions still remain. Who actually chose this (non-Mexican) image? Did they do so because of some resemblance to a known person? Was the vignette chosen because Pani thought she was the spitting image of his mistress?.

On 27 June, as Huerta was travelling by train from New York to El Paso, presumably as the first step towards his coup d’état, he was apprehended and charged with conspiracy to violate U.S. neutrality laws. After some time in the U.S. Army prison at Fort Bliss, he was released on bail but remained under house arrest due to the risk of flight to Mexico. Later he was returned to jail, and while confined, died of cirrhosis of the liver. On 15 November 1915 the ABNC instructed its factory to have all dies and plates placed in its vaultsABNC.

José Victoriano Huerta Márquez was born on 22 December 1850 in Colotlán, Jalisco. He decided upon a military career early on as the only way of escaping the poverty of Colotlán, graduated from the military academy in 1877, and during the following decades served throughout the country. In 1907 he retired from the army on grounds of ill health but rejoined in 1910 on the eve of the Revolution. His actions against the Zapatistas in Morelos forced a break between Madero and Zapta, who rebelled against Madero immediately after his November 1911 election.

José Victoriano Huerta Márquez was born on 22 December 1850 in Colotlán, Jalisco. He decided upon a military career early on as the only way of escaping the poverty of Colotlán, graduated from the military academy in 1877, and during the following decades served throughout the country. In 1907 he retired from the army on grounds of ill health but rejoined in 1910 on the eve of the Revolution. His actions against the Zapatistas in Morelos forced a break between Madero and Zapta, who rebelled against Madero immediately after his November 1911 election. Ignacio Argüelles Bravo was born in Guadalajara, Jalisco on 31 August 1837. He joined the army, fighting in the civil war and then fought the French when they invaded Mexico in 1862. He was taken prisoner of war after the battle of Puebla and deported to France, where he remained for a year, then returned to Mexico, to join General

Ignacio Argüelles Bravo was born in Guadalajara, Jalisco on 31 August 1837. He joined the army, fighting in the civil war and then fought the French when they invaded Mexico in 1862. He was taken prisoner of war after the battle of Puebla and deported to France, where he remained for a year, then returned to Mexico, to join General