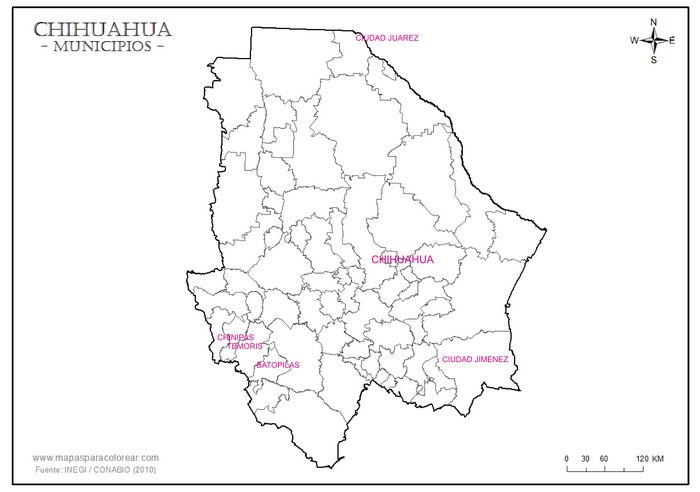

Local revolutionary issues

Madero's proposed bond issue 1911

There exists a draft of a decree, dated 28 January 1910 (sic, surely 1911), issued from the banks of the Rio Bravo, in Mexican territory, and signed by Francisco Madero as Presidente Provisional, Jefe de la Insurrección, that empowers Abraham González, Alfonso Madero, Federico González Garza, Adrián Aguirre Benavides and Braulio Hernández (or any three of them) to raise a loan of a million dollars by means of bonds or notes (bonos ó billetes al portador)CEHM, Fondo Federico González Garcia, carpeta 8, legajo 716.

On 1 March 1911, Francisco Madero wrote from Washington to his brother Ernesto with another draft of this decree in the name of the President of the provisional government. This version established a commission composed of Alfonso Madero, Federico González Garza and Adrián Aguirre Benavides to raise a loan of a million pesos and to issue all the bonds or notes (bonos ó billetes) necessary for this purpose, to be redeemed within a year of their establishment as the de facto government. Madero wrote that the decree should be dated to the time that he was at GuadalupeCEHM, Fondo Federico González Garcia, carpeta 8, legajo 1325.

Both versions of this decree (with the total fixed at one million U.S. dollars) exist, with the earlier date 15 February 1911 and the place of issue Guadalupe, in the Bravos district, Chihuahua.CEHM, Fondo Federico González Garcia, carpeta 10, lejagos 1296 and 1297. However, it seems that this decree remained just an aspiration.

Local issues during the 1911-1915 revolution

During the Mexican revolution, especially in the earliest days, a few local military commanders issued paper currency to pay their troops or to purchase suppliesCredit notes (vales) and requisition slips are incredibly common but cannot be considered currency.

During the Mexican revolution, especially in the earliest days, a few local military commanders issued paper currency to pay their troops or to purchase suppliesCredit notes (vales) and requisition slips are incredibly common but cannot be considered currency.

Chínipas

When in April 1911 nearly fifteen hundred revolutionaries under Rafael Becerra, of Urique, besieged Chínipas for nearly eight weeks Reinaldo Almada, the jefe político interinoFrom 16 February to 27 June (previously Tesorero Municipal of Chínipas from 17 December 1908 to 11 February 1911) of the Arteaga district, ordered the printing of 17,000 pesos in vouchers to cover the salaries of the local 5º Batallón. When hostilities came to an end with the treaty of Ciudad Juárez the vouchers were made good by the State TreasuryFrancisco R. Almada, [ ], describes them as certificates drawn on the state treasury (certificados contra la Tesorería General).. None are known to exist.

Temoris

In 1912 the Maderista Feliciano A. Díaz took up arms in Temoris and on May 14 cleared the Orozquista Ramón Valenzuela from Chínipas. A little later he took command of Batopilas and in September drove back into Sinaloa Blas Retes and Francisco Quinteros who had captured Batopilas and Lluvia de Oro. In 1913 Díaz issued his own currency in TemorisJ. Remigio Agraz, La Casa de Moneda de Chihuahua, in VII Simposio de Historia de Sonora, Hermosillo, 1982. No examples are known.

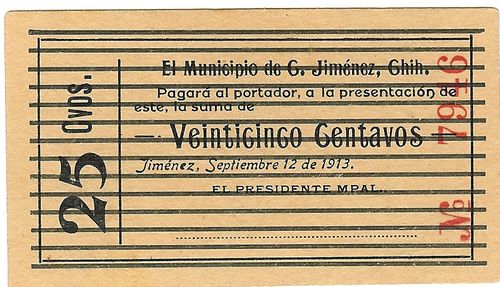

Ciudad Jiménez

Presumably because of a shortage of small coins the Municipio de Ciudad Jiménez, in the south of the state, issued a cartón for 25 centavos dated 12 September 1913 and signed by the Presidente Municipal. The notes are comparable with the private issues in use around Hidalgo de Parral at the same time (see Vales issued in Parral) and may have been redeemed under Villa’s decree of 23 December.

M945 25c Municipio remainder with original text erased

| from | to | total number |

total value |

||

| 25c | includes number 7946 |

as stated, these were to be signed by the Presidente Municipal who at this time was [ ]. (Miguel González was elected Presidente Municipal in January 1913Periodico Oficial, 2 March 1913).

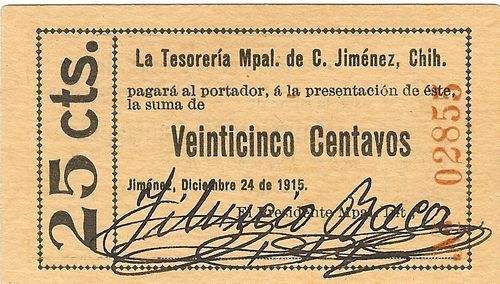

No issued examples are known but some unissued sheets were reused in December 1915, with the original text erased (as in the above image) and new text printed on the other side. This time the legend was Tesorería Municipal de Ciudad Jiménez.

M945 25c Municipio

M945 25c Municipio

| from | to | total number |

total value |

||

| 25c | includes numbers 02855 to 04906 |

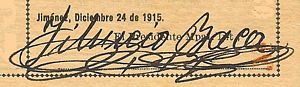

These later notes were still for 25 centavos, were dated 24 December 1915 and signed by the interim Presidente Municipal Tiburcio Baca.

|

After the split between Villa and the Constitutionalists Baca allied himself with the latter. As Presidente Municipal of Ciudad Jiménez he organised a Social Defense corps to protect the population from the excesses of Villa's troops. In the last days of October 1916, Villa kidnapped Baca, his brother-in-law, Darío Acosta, and his neighbour Jorge Soto, demanding that their families pay a ransom, which could not be covered because the constant looting had exhausted their resources. Furious, Villa ordered the torture of his prisoners and on 3 November he transferred them to Estación Morita, in Valle de Allende. Baca was beaten savagely and, together with Dario Acosta, buried alive up to the chest and shot dead. Another version relates that the prisoners had been buried up to their necks and Villa had ordered a cavalry platoon to ride over themRubén Rocha Chávez, Tres Siglos de Historia, Parral, 1981. |

|

Ciudad Juárez

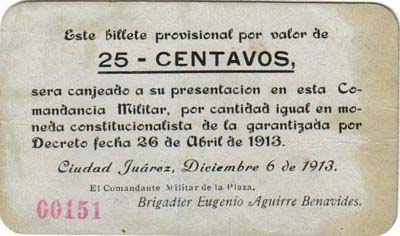

M937 25c Comandancia Militar

M937 25c Comandancia Militar

| from | to | total number |

total value |

||

| 25c | includes number 00151 |

On 28 November 1913 the American consul in Ciudad Juárez reported that “coin money has wholly disappeared and no fractional (Federal?) currency to take its place; fiat money of large denominations issued by the Constitutionalist of the States of Coahuila and Sonora has appeared here and the rebels are endeavoring to force it on the public which is considered equal to confiscation of goodsSD papers, 812.00/9952.

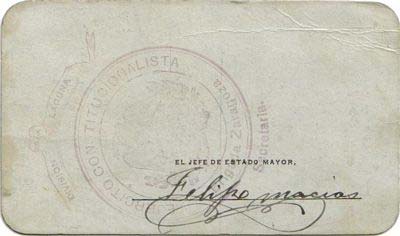

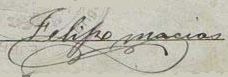

A couple of historians report that Adrian Aguirre Benavides, an early supporter of Villa, whilst jefe militar of Ciudad Juárez in December 1913, printed his own currency to pay his troops. Villa was not amused by this insubordination and almost had Aguirre Benavides shotJ. Remigio Agraz, La Casa de Moneda de Chihuahua, in VII Simposio de Historia de Sonora, Hermosillo, 1982: Francisco Almada, Diccionario, Historia, Geografia y Biografia Chihuahuenses, Chihuahua,. Neither Aguirre Benavides nor his brother refers to this issue in their memoirs, but a 25c carton survives. This was issued by Eugenio Aguirre Benavides, as Comandante de la Plaza, and signed on the reverse by Felipe Macias, El Jefe de Estado Mayor, of the Brigada Zaragoza.

|

In September 1913 he was appointed Commander of the Zaragoza Brigade and participated in various campaigns. When Villa split with Carranza, Aguirre Benavides continued to side with Villa. He was a delegate to the Aguascalientes Convention and was part of its War Commission. He was appointed Commander of the Convencionista Army and held the position of Undersecretary of War and Navy in the cabinet of Eulalio Gutiérrez. At the end of 1914 Aguirre Benavides was about to break the line that protected Tampico (before the famous Battle of El Ébano) but was driven back by the Carrancistas; if he had done so, the Villista troops would have taken the port and perhaps Villismo would have won, because it would have had access to the oil companies and the money that was generated in the customs. In mid-1915 he was taken prisoner in the vicinity of Los Aldamas, Nuevo León, by Colonel Teódulo Ramírez, and died by firing squad on 2 June 1915. |

|

|

Felipe Macias participated with the rank of Major in the capture of Torreón in September and October 1913. He was then put in charge of the First Regiment of the Brigada Zaragoza’s and Aguirre Benavides’s chief of staff. On 8 January 1915, with the rank of General, the Convention accepted his credential to be represented in the assembly by Melchor Menchaca. |

|

These notes were exchangable for Monclova currency at the Comandancia Militar.

It is also possible that Aguirre Benavides ran off some Monclova notes without authorisationThe Villistas had Monclova plates (Garland Roark, The Coin of Contraband, New York, 1964). Monclova notes are known with the validation ‘Division del Norte, Ejercito Constitucionalista, Jefatura de Armas’..

Since Carranza prohibited the use of scrip in his decree (núm. 14) of 28 December 1913 the practice must have been widespread.

Batopilas

In April 1914 Villa stationed Colonel Gabino Durán at Batopilas and ordered him to work the mines there. Durán paid his men in notes that he had printed at Batopilas and later had these redeemed for Constitutionalist money. Almada states that this issue reached $63,000Francisco R. Almada, Diccionario, Historia, Geografia y Biografia Chihuahuenses, Chihuahua, 1952. A packet of these notes, totalling $369·85, was listed amongst the decommissioned currency in the Chihuahuan treasury in September 1915Periódico Oficial, 12 September 1915. Unless un paquete vales Gabino Durán referred to handwritten chits. but none is known to have survived. To achieve such a total there must at least have been notes for $1, 5c and 10c (or 10c and 25c).

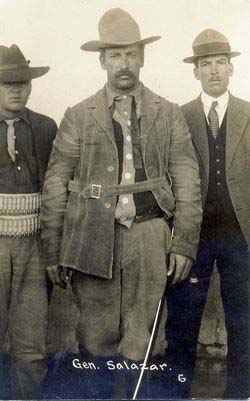

José Ines Salazar / Felix Díaz

In December 1914 the New York Times reported that a new revolutionary movement headed by General José Ines Salazar, recently launched in central Chihuahua, had placed in circulation its own currency. This money, printed in the United States, bore Salazar’s signature and the legend ‘Peace and Justice’ (Paz y Justicia)The New York Times, 19 December 1914: Fort Worth Star-Telegram, 30 December 1914. However, Salazar's attorney, Elfego Baca, of Albuquerque, said that Salazar had not as yet issued any manifesto, and the one recently given publication and credited to him was a fake. "[Salazar] will not issue any fiat money to conduct his revolution. He will conduct it without that, ... If any one tells you that money is being issued in the name of the Salazar revolution, tell him that he lies; it is not true"El Paso Herald, 29 December 1914.

José Ines Salazar had been a Magonista and then joined the Madero rebellion in 1910, but he turned against Madero and joined Orozco (or rather, Orozco joined him). In 1913, he supported Huerta against the revolutionaries, but after defeat at Tierra Blanca and Ojinaga fled to the United States.

José Ines Salazar had been a Magonista and then joined the Madero rebellion in 1910, but he turned against Madero and joined Orozco (or rather, Orozco joined him). In 1913, he supported Huerta against the revolutionaries, but after defeat at Tierra Blanca and Ojinaga fled to the United States.

He was detained in Fort Bliss and then Fort Wingate but just before a trial for perjury, on 16 November he was sprung from the jail in Albuquerque. He surfaced publicly on 5 December in El Paso when he joined with other exiles backing a return by Huerta and Orozco. For six months in 1915 he was active in Chihuahua attempting to organise a counterrevolution against the Carranza government but the arrest of Huerta and Orozco in late June 1915 extinguished that plan. He returned to New Mexico in July 1915, surrendered to law officers and spent nearly five months incommunicado at the penitentiary in Santa Fe before being acquitted of the perjury charge. Freed in December 1915, he returned to northern Mexico. In May 1916, Carranza’s federal soldiers captured and imprisoned Salazar in Ciudad Chihuahua. In September 1916, Villa raided the town and released all the prisoners. Salazar again switched allegiance, now backing his former arch-enemy Villa. In September 1916 he became Villa’s chief of staff, largely responsible for holding his army together during General Pershing’s Punitive Expedition. In April 1917 he commanded over a thousand troops, but that month he suffered the first of a series of defeats. By 9 August 1917 only three soldiers remained with him, and all perished in a shoot out that day.

There was, in fact, some basis for the New York Times report, but the issue was intended for Felix Díaz (See Felix Díaz).

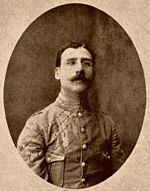

Tiburcio Baca came from a powerful local family and was originally an adherent of Villa

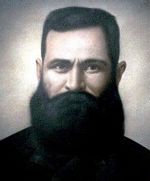

Tiburcio Baca came from a powerful local family and was originally an adherent of Villa Eugenio Aguirre Benavides was born in Parras de la Fuente, Coahuila, on 6 September 1884. He participated in the Maderista movement, fought against Orozco in 1912, and after Huerta’s coup, joined the Constitutionalists.

Eugenio Aguirre Benavides was born in Parras de la Fuente, Coahuila, on 6 September 1884. He participated in the Maderista movement, fought against Orozco in 1912, and after Huerta’s coup, joined the Constitutionalists.