Establishment of El Banco de Sonora

On 18 September 1897 a concession to establish a bank was granted to Prospero Sandoval, Baudelio SalazarBaudelio Salazar was an assayer (ensayador) in 1879 (El Siglo Diez y Nueve, 16 July 1879) and had moved to Chihuahua by 1894. He was a deputy in the Chihuahua legislature in September 1895 and setting up a mining exchange (bolsa de minería) in Chihuahua in 1896 (Semana Mercantil, 6 January 1896) (an American) and Luis A. MartínezLa Constitución, 1 October 1897. The consequent contract was agreed between the bank’s board (the three concessionaires plus Juan de Dios Castro as vice-president) and the state executive on 6 December and approved by the state legislature on 15 DecemberLey núm. 10. (La Constitución, 25 December 1897) and the bank finally opened its doors on 10 January 1898.

The bank was capitalised at 500,000 pesos, of which Ramón Corral took 50,000; Manuel Mascareñas 50,000; Augustus Abbott 200,000 with the balance held by P. Sandoval and Co. and the principal merchants of Guaymas and HermosilloJ. R. Southworth, El Estado de Sonora. Sus Industrias, Comerciales, Mineras y Manufactureras, Nogales, Arizona, 1897.

Ramón Corral Verdugo was born of an undistinguished family on the Hacienda de las Mercedes, Alamos in 1854. Corral earned his reputation and multiplied his wealth through business and mining. Thus he was not a hacendado but a speculator in the world of finance as well as an efficient administrator and able politician, who began his political career by joining the rebellion against Governor Ignacio Pesqueira, was elected to Congress in 1877, and eventually became president of the Chamber of Deputies. Shortly afterwards he returned to Sonora as lieutenant governor, then became its governor, and from that office went on to be mayor of the Federal District, vice-president of the Republic, and minister of Gobernación, the key cabinet post, in 1904 and 1910.

Ramón Corral Verdugo was born of an undistinguished family on the Hacienda de las Mercedes, Alamos in 1854. Corral earned his reputation and multiplied his wealth through business and mining. Thus he was not a hacendado but a speculator in the world of finance as well as an efficient administrator and able politician, who began his political career by joining the rebellion against Governor Ignacio Pesqueira, was elected to Congress in 1877, and eventually became president of the Chamber of Deputies. Shortly afterwards he returned to Sonora as lieutenant governor, then became its governor, and from that office went on to be mayor of the Federal District, vice-president of the Republic, and minister of Gobernación, the key cabinet post, in 1904 and 1910.

Corral held 10% of the bank’s shares. As under the bank’s concession no official or employee of the executive branch could serve on its board Corral was never a director though his daughter’s portrait graced the bank’s notes.

Manuel Mascareñas Porras was born in Durango on 28 October 1848, came to Sonora in 1869 and set up a business in Guaymas. In 1873 he married Luisa Navarro Montijo, daughter of Cayetano Navarro. He spent most of the 1870s in the port, where he dabbled in commerce and politics. He served several terms on the Guaymas council. He later moved to Hermosillo, where he formed a partnership with Rafael Ruíz and opened a small retail business. Mascareñas continued to take part in politics, being elected several times to the Hermosillo council. In 1880 President Díaz established the customs post at Nogales: Mascareñas realised the possibilities and in 1885 moved his business to that town. He purchased the hacienda Santa Barbara which consisted of more than 15,000 hectares. By 1900, after acquiring adjacent lands, he had amassed more than 36,000 hectares.

Manuel Mascareñas Porras was born in Durango on 28 October 1848, came to Sonora in 1869 and set up a business in Guaymas. In 1873 he married Luisa Navarro Montijo, daughter of Cayetano Navarro. He spent most of the 1870s in the port, where he dabbled in commerce and politics. He served several terms on the Guaymas council. He later moved to Hermosillo, where he formed a partnership with Rafael Ruíz and opened a small retail business. Mascareñas continued to take part in politics, being elected several times to the Hermosillo council. In 1880 President Díaz established the customs post at Nogales: Mascareñas realised the possibilities and in 1885 moved his business to that town. He purchased the hacienda Santa Barbara which consisted of more than 15,000 hectares. By 1900, after acquiring adjacent lands, he had amassed more than 36,000 hectares.

At first Mascareñas focused his attention on cattle ranching, importing American Herefords to breed with Mexican cattle. In a few years he had one of the most productive and profitable cattle enterprises in the north, exporting large amounts of beef to the United States by rail. The ranch also produced wheat, corn, and other agricultural staples. It was not long before Mascareñas became involved in Nogales politics. By 1887 he had been elected Presidente Municipal of Nogales, later becoming the Mexican consul in Nogales, Arizona, and serving in that capacity until the outbreak of the Mexican Revolution.

He died on 19 November 1936, in Alameda, California, at the age of 88.

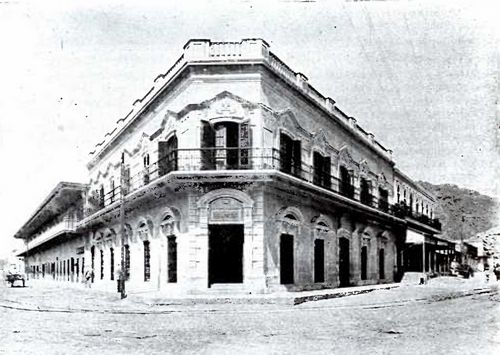

Luis Martínez' house in Guaymas

Luis A. Martínez was the first and most genuine of the Sonoran capitalists: starting with nothing, he managed to build up a large number of undertakings whilst also devoting himself to politics. He came to Guaymas in 1886, began as an employee of the port authority, and established his own casa comercial near the quay in 1892. He was one of the main shareholders in the Compañía de Transportes Marítimos of Mazatlán, for which he was the Guaymas agent. This merged with its competitor, the Línea de Navegación del Pacífico, to form the Compañía Naviera del Pacífico, and Martínez retained his shareholding and agency. By the first decade of the century the Compañía Naviera del Pacifico was the largest in MexicoJorge Murillo Chisem, Apuntes para la Historia de Guaymas, Sonora, 1990. Martínez was also a founding shareholder of the Compañía Industrial y Explotadora de Maderas, the largest diversified machine shop on the West Coast and, as well as the Banco de Sonora, a founding shareholder in the Banco Hipotecario y Agrícola del Pacífico.

Luis A. Martínez was the first and most genuine of the Sonoran capitalists: starting with nothing, he managed to build up a large number of undertakings whilst also devoting himself to politics. He came to Guaymas in 1886, began as an employee of the port authority, and established his own casa comercial near the quay in 1892. He was one of the main shareholders in the Compañía de Transportes Marítimos of Mazatlán, for which he was the Guaymas agent. This merged with its competitor, the Línea de Navegación del Pacífico, to form the Compañía Naviera del Pacífico, and Martínez retained his shareholding and agency. By the first decade of the century the Compañía Naviera del Pacifico was the largest in MexicoJorge Murillo Chisem, Apuntes para la Historia de Guaymas, Sonora, 1990. Martínez was also a founding shareholder of the Compañía Industrial y Explotadora de Maderas, the largest diversified machine shop on the West Coast and, as well as the Banco de Sonora, a founding shareholder in the Banco Hipotecario y Agrícola del Pacífico.

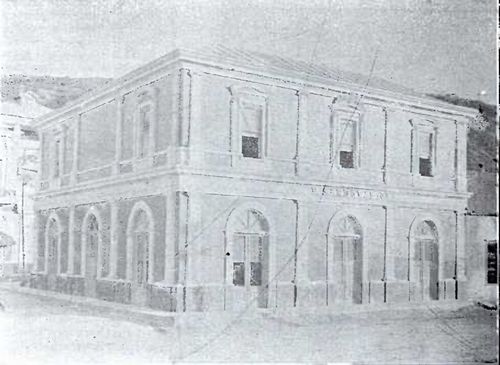

Offices of P. Sandoval and Co. in Nogales

P. Sandoval and Co. commenced business in 1884 and were the oldest established customs brokers in Nogales. They had their own commercial business as well as being commission merchants and customs agents for many commercial houses and a number of the leading mines in Sonora and a banking house for payments to mining companies in the districts of Altar, Magdalena and Arizpe. The firm consisted of Próspero and Aurelio Sandoval, sons of José V. Sandoval, who had been Presidente Municipal of Guaymas in 1856. Próspero was the collector of stamp tax, whilst Aurelio had the agency for the Ministry of Public Works. They also owned large tracts of land in and around Nogales.

Augustus Abbott was an American with experience in banking, having been manager of the California State Bank at SacramentoSacramento Daily Union, 19 March 1898 and part-owner and manager of the rich Santa Rosalia mine in Arizpe, Sonora. Abbott and his California friends subscribed for about two-fifths of the bank’s stock and he assisted in its organization but, according to an interview in August 1897, did not intend to take any further part in its managementThe Oasis, Nogales, 14 August 1897.

On 25 January 1898 Abbott married Miss Luella Saxtorph of East Oakland, and immediately after the wedding took his bride to Mexico. A month later, he was reported to be on the run, flying through the country to escape the wrath of the directors and stockholders of the Santa Rosalia mine. It was claimed that he had failed to account for several thousand dollars that had disappeared while he was superintendent and on 1 March a suit for $30,000 was filed and an attachment issued against his 12,500 shares in the mineSacramento Daily Union, 19 March 1898. However, within a couple of months the matter had been settled, with the directors admitting that they had been mistaken and had failed to realize that, in accordance with Mexican law, Abbott kept his accounts in Mexican currency, where the peso was worth half a dollar. “$30,000” in the accounts in Mexican pesos converted to $15,000 in U.S. dollars. They had read the books wrong and everything was fineThe Oasis, 11 June 1898. Though things might have been a little more complicated, and smoothed overThe Sacramento Daily Union reported “As Superintendent of the rich Santa Rosalia mine in Mexico, Abbott was paid a salary of $250 a month, but his frequent and prolonged visits to this city and the attention which he paid to other enterprises in which he engaged in Mexico led to his retirement, and W. J. Coleman was appointed as his successor in November, 1897. Subsequently, in settling up the company's business, the Directors say, a number of vouchers, amounting to about $5,000, were not to be found. A full investigation of the company's affairs at Arispe, in the State of Sonora, Mexico, was instituted, and President John Daggett and other stockholders devoted more than three weeks in February and March to scrutinizing the books and business of the concern. They found that Abbott had transacted all the business of the Santa Rosalia .Mining Company in his own name and that the books of the company in reality were written as if private accounts. These facts and the discovery of excessive expense charges were immediately communicated by Daggett to the Directors here and legal steps were taken without delay to protect the company against loss by attaching Abbott's stock in this city.

While this investigation was going on Abbott and his newly wedded wife were spending their honeymoon in the City of Mexico. In some way he received word of the discoveries that have been made, and instead of returning to Hermosillo, where it was said he was about to enter into the banking business, he continued his journey to the United States. Since that time his movements have been followed as closely as possible by the company's attorneys, but they refuse to say more than to admit that they have good reason to believe that he was in Little Rock a few days ago.

Although the amount actually involved in the present suit is only about $30,000, it is said that the stock now under attachment, which has a market value of about $63,000, will not more than repay the company for the losses which the Directors believe they have suffered through Abbott's alleged mismanagement.

John Daggett, President of the company, was reticent when asked yesterday about the extent and manner of Abbott's operations. He stated merely that the former Superintendent owed the company money and that the Directors were puzzled over his recent movements. Secretary Hugh Tevis was scarcely more communicative, but he made no effort to disguise the fact that the company intended to proceed against Abbott with vigor.

Both officers of the company said that it had been their purpose to keep the matter from the public, but they were not inclined to minimize the seriousness of the dilemma in which Abbott found himself. They would not commit themselves absolutely to any expression of opinion as to what developments the present investigation would lead to, but they were satisfied that the company had insured itself against loss by its prompt action.

The same disinclination to talk was shown by Gavin McNab, attorney for the Santa Rosalia Mining Company. He stated merely that the suit was the result of differences between the company and Abbott and that all the facts would be shown in court at the proper time. More than that McNab refused to say” (Sacramento Daily Union, 19 March 1898).

Then, in June 1898, The Oasis reported “The suit, however, it is now determined, meted out an injustice to the defendant, and its instigation was solely due to the fact that the directors of the plaintiff corporation were either in ignorance or did not stop to consider the fact that Mexico is a silver standard country and that two of its dollars equal only one of the coinage of the United States in the commercial world. Since the directors of the mining corporation have been apprised of the fact they have dismissed the suit against Mr. Abbott, the dismissal being prompted by the fact that they had no suit to prosecute, as their books balanced to the cent with those of their former superintendent, who was immediately exonerated when the comparison was made.

Abbott was the trusted employe and business associate of the officers of the company for almost three years into the management of one of the richest mining properties owned in San Francisco - and it was not until several months after his retirement from the position of superintendent that the management determined that suit for the recovery of a large amount of money must be instituted. The directors were of the opinion that they had dug up a deep plot, that irregularities existed in Abbott's accounts and that he had left on a tour abroad for the sole purpose of remaining out of the reach of processes issuing out of California courts. That Abbott was absent there could be no doubt, and owing to this fact suit for the recovery of $30,000 was filed against him and an attachment was issued against 13,500 shares in the mining corporation, of which he was owner, held in escrow by the Bank of California and on the secretary's books. No service on Abbott was made, but he became cognizant of the facts of the case while traveling, and he informed his attorney Colonel W. R Harlow, of Nogales, Arizona. Abbott was non-plussed at the action of the directors, but he continued on his trip, trusting to Colonel Harlow to see that the complainants were properly appraised of the facts. Colonel Harlow has completed his labors in behalf of Abbott, has apprised the directors of the facts of the case, has received their word that the former superintendent does not owe one cent to the corporation and is now on his way home.

"The facts of the transaction and circumstances that so startled the directors of the corporation are these,” said Colonel Harlow last evening. “Mr. Abbott was placed in charge of the mining property, and he went into Mexico to see that its development was properly conducted, and it was his desire to obey the laws of Mexico instead of his wish to disobey the laws of the United States that led to the suit being filed against him. The laws of Mexico make it necessary to keep the books of all corporations in Spanish. This being the fact, when the income from the mine was balanced it was placed in the books in figures representing its value in coin of the realm in which it was produced. For instance, one of the items on the Mexican books that roused the suspicions of the directors was one of $44,000, representing a like number of Mexican coins of that denomination, while the books of the directors only credited the output of the mine wit $22,000, half the amount placed to its credit by its superintendent on its accounts. Many similar conditions were found to exist, and the directors, when they received the books from Mexico; immediately concluded that a shortage existed. Mr. Abbott trusted to the knowledge of the directors regarding the difference of money values to set them right regarding the accounts, but in their anxiety to protect themselves against loss they did not stop to consider the condition of affairs.

In the meantime Mr. Abbot had arrived from Mexico, and after marrying one of Oakland's belles, started on his wedding tour. He went to Mexico and then started on a tour of the United States. It was the tour of his honeymoon that took him away from the city and his business which led some of the directors to believe that he was traveling solely to escape summons in the action which has been filled against him. He learned of the suit, however, and instructed me to care for his interests and investigate the allegations of the directors. This I did. Two months ago I went to Mexico and investigated the books of the company still remaining there, and learned of the output of the mine. I soon became acquainted with the condition that had led to the misunderstanding, and returned to this city. The matter in the meantime had been placed in the hands of James McNabb by the directors for settlement, and together we went over the books of the company. An expert accountant was employed and when he had concluded his labors it was found that there was not one cent due from my client. To corroborate this statement, I have in my possession a receipt from the company for all of its demands against Mr. Abbott. The matter which treated considerable surprise at the time, has proven to be based on a film of circumstances which, if the directors had investigated, would have disappeared without even the trouble incurred by the filling of a complaint for money which was not due.”(The Oasis, 11 June 1898).

Other shareholders included the bank’s first president and vice-president, Rafael Ruíz and Juan de Dios Castro. The full list in December 1897 was

| number of shares | value | |

| A. Abbott | 500 | $50,000 |

| Manuel Mascareñas | 500 | $50,000 |

| Ramón Corral | 350 | $35,000 |

| José María Elías | 250 | $25,000 |

| Luis A. Martínez | 250 | $25,000 |

| Rafael Ruíz | 250 | $25,000 |

| Baudelio Salazar | 250 | $25,000 |

| G. A. Villaseñor | 250 | $25,000 |

| Ignacio Bonillas | 200 | $20,000 |

| Carmelo Echeverría | 200 | $20,000 |

| Próspero Sandoval | 200 | $20,000 |

| Arturo Serna | 200 | $20,000 |

| Víctor Aguilar | 100 | $10,000 |

| F. A. Aguilar Sucs | 100 | $10,000 |

| F. Loaiza y Cía. | 100 | $10,000 |

| Bley Hermanos | 100 | $10,000 |

| Fred Herrera | 100 | $10,000 |

| José Camou | 100 | $10,000 |

| Juan de Dios Castro | 100 | $10,000 |

| Miguel Gaxiola | 100 | $10,000 |

| Lic. Miguel A. López | 100 | $10,000 |

| Miguel Latz y hermano | 100 | $10,000 |

| Enrique Peña | 100 | $10,000 |

| Rodolfo Rodríguez | 100 | $10,000 |

| Gustavo Torres | 100 | $10,000 |

| Agustín Freese | 50 | $5,000 |

| W. Yberry e hijos | 50 | $5,000 |

| Gerardo May | 50 | $5,000 |

| Juan Bojórquez (hijo) | 50 | $5,000 |

| Gaspar Zaragoza | 50 | $5,000 |

| Antonio Calderón |

In July 1901 the bank increased its capital to $1m and the shareholders were joined by

| Bartolomé R. Salido | ||

| José María Miranda | ||

| Elías Luketich | ||

| Max Müller | ||

| Samuel L. Bringas | ||

| Virginia R. de Tonella | ||

| Juan P. M. Camou | ||

| José C. Camou | ||

| Miguel A. López | ||

| Francisco GándaraAGHES, NP. Taide López del Castillo, Hermosillo, 15 July 1901 |

On 20 August 1905 the bank increased its capital to $1.5m and and in February 1906 new shareholders were

| Carlos Busjacquer | ||

| Fernando Montijo | ||

| George Grünig | ||

| Alejandro. F. Tarín | ||

| Carmen Serna Vda. de Gándara | ||

| Luis BrauerAGHES, Alberto Flores Juez 1º de 1ª Instancia. Hermosillo, 17 February 1906 |

The proofs for the bank’s notes were approved in February and March 1898The proofs of the $5 were approved by Juan de Dios Castro, on 7 February; those of the $10 were approved by R Ruiz, on 21 February, and those of the $20, $50, $100 by Max Müller, on 18 March (ABNC) and the notes themselves began to circulate in March. The notes were printed by the American Bank Note Company and bore the portrait of Ramón Corral’s daughter, Hortencia Corral Vélez, though whatever this adds in uniformity to the series it detracts from each note. Only the hundred pesos note, with its sailing ships, possibly an allusion to Luis Martínez and the importance of Guaymas, is particularly memorable.

On 16 August 1898 the Customs Administrator at Nogales, Carlos G. Mertens, wrote to the Minister of Finance, José Yves Limantour, that he had just learnt that people (led by Sandoval) were denigrating him with governor Corral because he was not accepting the Banco de Sonora’s notes. Mertens said that it would be much easier for him to accept banknotes than silver, and he had no interest which bank they came from, but 54% of his receipts were paid into the agent of the Banco Nacional de México, which only accepted their notes and those of the Banco de Londres y México, whilst some were paid to the Administrador del Timbre, who also would not accept Banco de Sonora notes. The Banco de Sonora had tried to flood the local market with its notes, to drive out the others, but whilst the Banco Nacional de México and Administración del Timbre refused to accept them, there was nothing he could doCEHM, Colección José Y. Limantour, carpeta 35, legajo 9189. On 24 August Limantour replied that this conduct accorded with the government’s agreement with the Banco Nacional de México, and that the Banco de Sonora would undoubtedly be satisfied with the explanationCEHM, Colección José Y. Limantour, carpeta 35, legajo 9190.