Félix Díaz

Félix Díaz was the nephew of president Porfirio Díaz. Imprisoned by Madero for rebellion, he escaped from jail during the decena trágica and was a party to the Pacto de la Embajada, which installed Huerta as President and allowed Díaz to run as presidential candidate on the next election. Huerta did not honour his part of the agreement and ultimately sent Díaz into exile to New York and later Havana.

Cecilio L. Ocón

On 17 December 1914 the American Bank Note Company gave Cecilio L. Ocón a quotation for 28,100,000 notes in five denominations from one to a hundred pesos thus

| Number | Total value | |

| $1 | 20,000,000 | $ 20,000,000 |

| $2 | 5,000,000 | 10,000,000 |

| $5 | 2,500,000 | 12,500.000 |

| $10 | 500,000 | 5,000,000 |

| $100 | 100,000 | 10,000,000 |

| 28,100,000 | $ 55,500,000 |

and by January 1915 had prepared modelsABNC. Ocón was a close personal supporter of Felix Díaz and been involved in the assassination of president Madero: he later was Díaz’s financial agent and supported several of his counterrevolutionary attemptsJosé Cecilio Luis Ocón Ruday was born in Mazatlan, Sinaloa, on 27 August 1879.

In October 1912 he met with the former Porfiristas Manuel Mondragón and Gregorio Ruiz in Havana to forge a military coup against President Francisco I. Madero in a plan that consisted of freeing the generals Bernardo Reyes and Félix Díaz from prison and kidnapping and shooting Madero. At the start of the decena trágica Bernardo Reyes and Félix Díaz were released from prison but Reyes was subsequently killed in combat. Ocón was quartered in La Ciudadela with the rebels Manuel Mondragón and Félix Díaz receiving supplies from the resident entrepreneurs of Mexico City, including Ignacio de la Torre, son-in-law of the general Porfirio Díaz and the Asturian Íñigo Noriega.

Ocóne was responsible for the murder of Gustavo Madero, brother of the president Francisco I. Madero, who was taken prisoner in the Gambrinus restaurant at the same time as the president with the vice president José María Pino Suárez, Federico González Garza and Felipe Ángeles were taken prisoner by General Aureliano Blanquet. Gustavo was taken to La Ciudadela and personally handed over to Ocón, who after slapping him ordered the cadets of the Escuela de Aspirantes to do with him what they wanted They were vicious beating him, torturing him at bayonet point and leaving him blind by gouging out his only healthy eye and then shooting him dead. Ocón also witnessed the murder of Francisco Madero and José María Pino Suárez.

Ocón was present at Huerta's inauguration along with other personalities such as ambassador of United States Henry Lane Wilson. During the first months of Huerta’s dictatorship he had to deal with the constant accusations of being involved in the murders of the Maderos and of having been the promoter of the military coup. When Huerta broke with his ally Félix Díaz, Ocón fled to the United States from where he later emigrated to Cuba. Some time later he settled with his family in Spain, from where the triumphant revolutionaries would request his extradition to Mexico to be tried before a court martial in September 1914. Their properties were expropriated by the Carranza supporters.

At the beginning of 1916, in complicity with Félix Díaz, Ocón staged an uprising against Venustiano Carranza, but failed because no one supported the rebellion. Ocón was Félix Díaz’ financial representative in the United States. Not only did he fail to obtain funds, but he also had permanent problems with the political representative of Felicismo, Pedro del Villar.

After Carranza’s assassination Ocón became interested in participating in other rebel movements but was not accepted due to his personal background and sought to do business with banana and henequén companies, which were never successful. He was ostracized and anonymous, so details of his later life are unknown, although it is said that he tried to achieve success as a television entrepreneur. It is speculated that he died in 1948. . For this reason I believe that this correspondence, though placed in the Huerta folder, refers to a proposed Díaz issue. The 17 December quotation was sent to Ocon, care of Martin Stocker, at 105 “C” St., S. E., Washington, D. C. so identifying Stocker might help in placing this issue.

El Ejército Reorganizador Nacional

In early 1915 the ABNC received orders for notes for the Ejército Reorganizador Nacional, which was the name of Díaz’ movement. These were to carry the legend “Paz y Justicia” and be signed by the Contador General and Díaz as General en Jefe. The notes stated that they could be redeemed on a New York or San Francisco bank at that rate of 12c U.S. gold for each peso (por el Banco … en New York o el Banco … en San Francisco a razón de doce centavos oro americano por cada peso)”, hardly likely to inspire immediate confidence.

The ABNC produced some models.

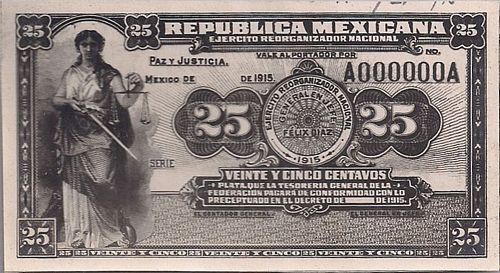

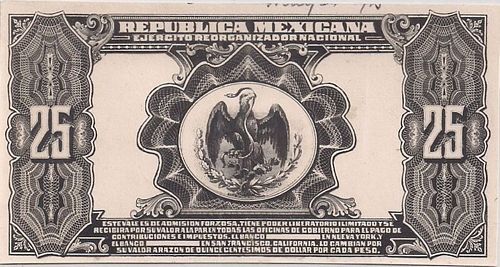

M1279 25c Ejército Reorganizador Nacional

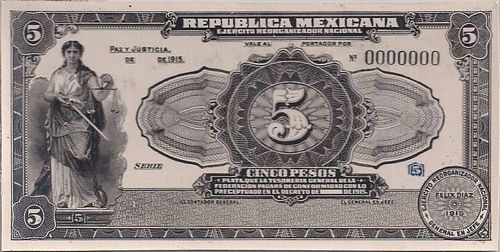

M1280 $5 Ejército Reorganizador Nacional (type 1)

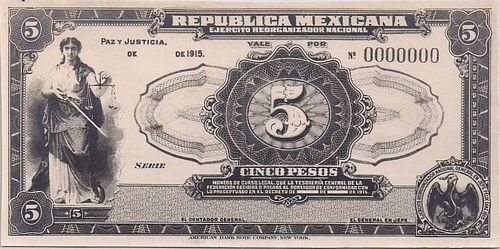

M1280.5 $5 Ejército Reorganizador Nacional (type 2)

Nothing came of this order and in February 1916 the ABNC destroyed the models it had made for the 25 centavos and 5 pesos notes. Díaz returned to Mexico in May 1916 as the leader of his Ejército Reorganizador Nacional, but his revolt was unsuccessful.

Strangely, on 19 December 1914 the New York Times reported that a new revolutionary movement headed by General José Ines Salazar, recently launched in central Chihuahua, had placed its own currency in circulation. This money, printed in the United States, bore Salazar’s signature and the legend ‘Peace and Justice’ (Paz y Justicia)The New York Times, 19 December 1914. However, Salazar’s attorney told the El Paso Herald, on 29 December, said that Salazar had not as yet issued any manifesto, and the one recently given publication and credited to him was a fake. “[Salazar] will not issue any fiat money to conduct his revolution. He will conduct it without that, ... If any one tells you that money is being issued in the name of the Salazar revolution, tell him that he lies; it is not true”El Paso Herald, 29 December 1914. The activities of the various (and overlapping) counterrevolutionary groups seem to have been confused.