Private issues

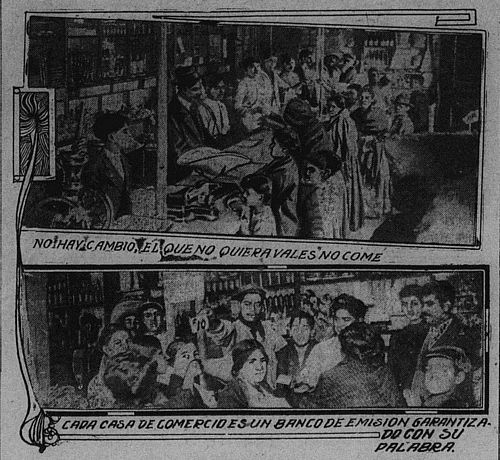

'NO HAY CAMBIO, EL QUE NO QUIERA VALES NO COME (No change. Whoever does not want to take vales does not eat)' and 'CADA CASA DE COMERCIO ES UN BANCO DE EMISION GARANTIZADO CON SU PALABRA (Every shop is a bank of issue guaranteed by its own word)'

(El Día, 15 May 1914)

Although the Constitucionalists occasionally aknowledged the necessity for, and even authorised the issue of, private issues the overriding position was they were illegal, as a contravention of Mexico's currency law. This was established in Carranza's decree núm. 14, when, while increasing his own issue, he prohibited the use of fichas, tarjas, vales u otros objetos de cualquiera materia, como signos convencionales en substitución de la moneda establecida por la ley de 25 de marzo de 1905 y del papel moneda.

In May 1914 a newspaper was complaining that the issue of vales by shops was becoming the most dangerous exploitation and also the surest way to drive out fractional currencyEl Día, Núm. 1, 15 May 1914. The article was illustrated and mentions among the establishments that had issued vales an egg-seller towards Niño Perdido and various important grocery stores in the Merced market.

By 8 September The Mexican Herald was reporting “The lack of fractional currency in the city reached an acute stage yesterday when it was practically impossible to obtain small change in any commercial establishment. This was especially noticeable in the smaller tiendas on the side streets, where customers clamored in vain for change after paying for a purchase in paper money. Most of the lecherias refused absolutely to sell milk unless the exact amount of the purchase was presented by the customer.

As this was almost impossible in many cases, numbers of persons were obliged to go without their daily supply of milk. The same trouble was experienced at the carbonerias, where the poor are accustomed to buy small quantities of charcoal. They could purchase nothing if they had not the exact amount ready, as the proprietor said they had no change.

At many of the small grocery stores purchasers were told when they presented a bank note that, as there was no change, they would have to receive vales on the store. There was a general protest against this plan, but as no articles would be sold under any circumstances when notes from one peso up were presented, many customers were compelled to accept the vales.

The saloons issued a large amount of their vales during the days immediately preceding their closing, and as these vales are good only at the particular saloon issuing them, patrons of these places can not make them pass in any other establishments and consequently will lose their amounts if the saloons remain closed indefinitely. Street car tickets are being accepted freely by all commercial houses as small change"The Mexican Herald, 20th Year, No. 6,941, 8 September 1914.

Athough the government was issuing 5c and 10c cartones, these were insufficient and also being hoarded, so ten days later the newspaper could report that “the situation caused by the lack of small change in the city again became very acute yesterday. In many business houses it was almost impossible to obtain fractional currency and a number of sales had to be refused by proprietors in cases where the prospective purchasers were unknown. … In the butcher shops and the small grocery stores of the city the situation was more accentuated, owing to the fact that the sales were smaller and the consequent need for fractional currency greater. Notwithstanding the regulations of the government against the issuing of vales, a number of stores emitted their paper, compelling customers to accept them or go without their change whenever a note was presented in payment of a purchase”. The 5c and 10c cartones seem to have disappeared and the only relief was the appearance of the 20c cartones, which were paid out to a number of the civil employees and rapidly found their way into circulation. Also Constitutionalist notes from the northern states were beginning to make an appearanceThe Mexican Herald, 20th Year, No. 6,951, 18 September 1914.

Almost a year later, on 9 August 1915 the governor of the Federal District issued a decree that only Carrancista issues were valid, so effectively repeating Carranza’s prohibition of any ‘vales, fichas o algún otro objeto que por medio de signos convencionales pudiera substituir a la moneda establecida por la ley de 25 de Marzo de 1905 y al papel moneda’The Mexican Herald, Año XXI, Núm. 7,315, 30 September 1915.

On 17 October Governor Heriberto Jara set a force of secret agents to work at watching grocery stores in the outlying districts which he had been informed were selling articles at a premium where notes were changed, refusing to make sales if notes were presented in purchases of less than fifty centavos or giving vales to the customer, so as to oblige him to come back, and other such abuses. According to warnings already given by the authorities, groceries or other establishments caught in these practices would be punishedThe Mexican Herald, 20th Year, No. 6,981, 18 October 1914.

On 4 December F. M. Busto, the Oficial Mayor Encargado de la Secretaría, remarking that many of the stores and cinemas in the capital had issued tarjetas to make up for the lack of small change, reminded them that they were prohibited by the decree of 28 December 1913 and threatened them with arrest or a fineEl Pueblo, Año II, Tomo II, Núm. 405, 7 December 1915.