La Brigada Morales y Molina

General Pascual Morales y MolinaPascual Morales y Molina was born in Jilotepec, Estado de México on 17 May 1876. In 1896 he graduated from and then taught at the the Instituto Científico y Literario in Toluca. Because of his Constitutionalist beliefs and professional standing, in 1914 he became Jesús Carranza’s chief of staff (jefe del Estado Mayor) and had a miraculous escape when Carranza was killed in an ambush at San Jerónimo, Oaxaca.

General Pascual Morales y MolinaPascual Morales y Molina was born in Jilotepec, Estado de México on 17 May 1876. In 1896 he graduated from and then taught at the the Instituto Científico y Literario in Toluca. Because of his Constitutionalist beliefs and professional standing, in 1914 he became Jesús Carranza’s chief of staff (jefe del Estado Mayor) and had a miraculous escape when Carranza was killed in an ambush at San Jerónimo, Oaxaca.

He served as a Brigadier General in the División del Centro. Then Venustiano Carranza appointed him governor and military commander of the Estado de México, a post he took up on 19 October 1915 when the Zapatistas were driven out of Toluca. During his governorship he promoted education and morality and waged a campaign of repression against the Zapatistas. In 1916, he left the governorship on becoming Attorney General (procurador general de la Nación). He died in Jilotepec, on 30 April 1928, having retired from public life. first had his brigade issue a small quantity of paper currency in Chilpancingo, with Carranza’s authorization. This was to satisfy the demand for change since the central government had sent funds, but in $100 Gobierno Provisional de México notes, which were for all practical purposes virtually useless.

Later, at the beginning of February 1915, after he had evacuated Chilpancingo for Acapulco, he continued issuing notes to pay his troops, until the total amount issued was quite sizeable.

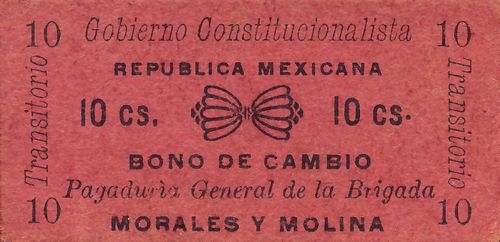

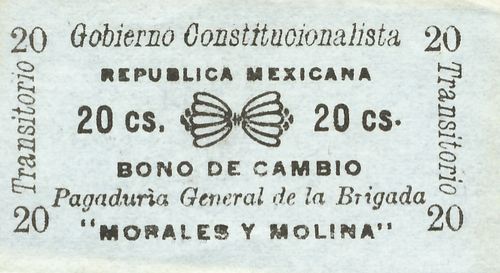

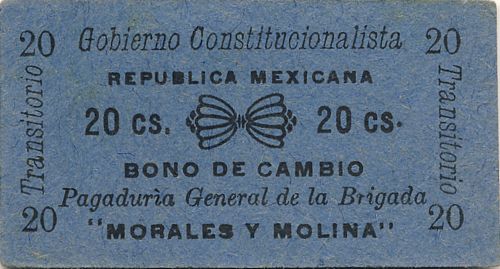

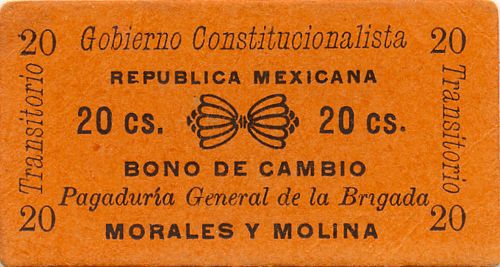

There was a series of cartones and notes in six denominations (10c, 20c, 50c, $1, $5 and $10), designated Bono de Cambio, as they were (originally) issued because of a shortage of change. That they were printed on a variety of coloured papers, and even graph paper, shows that the printers used whatever was at hand.

The 10c and 20c have a common design

M1884 10c Brigada Morales y Molina

M1884 10c Brigada Morales y Molina

with the 20c known in various colours (light blue, dark blue, orange).

M1885 20c Brigada Morales y Molina

M1885 20c Brigada Morales y Molina

M1885 20c Brigada Morales y Molina

M1885 20c Brigada Morales y Molina

M1885 20c Brigada Morales y Molina

M1885 20c Brigada Morales y Molina

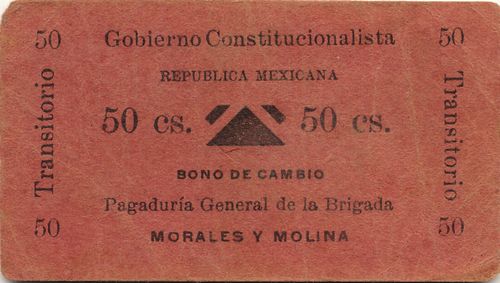

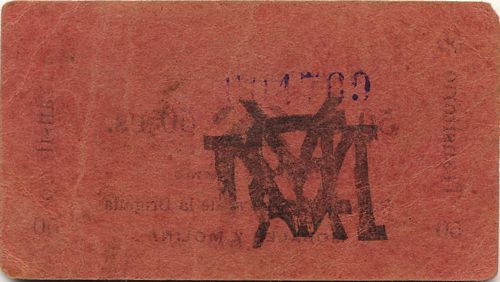

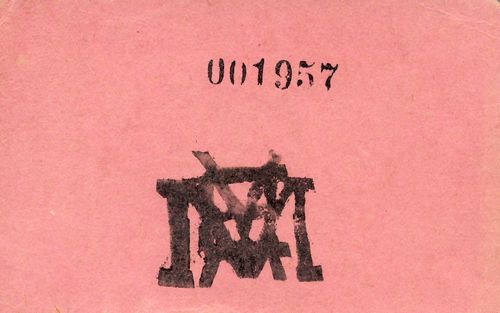

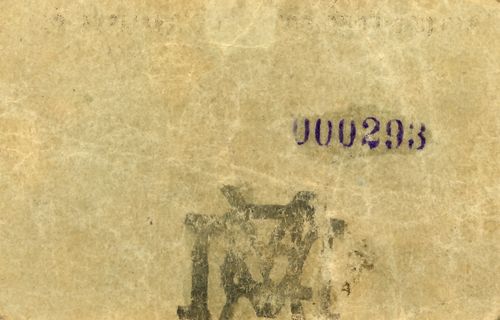

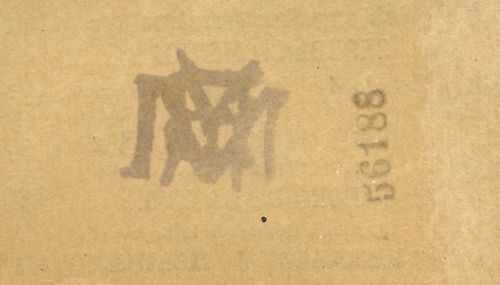

The 50c has a different centrepiece and are numbered and monogrammed on the reverse (two different monogram stamp swere used). They are known in light red

M1886 50c Brigada Morales y Molina

M1886 50c Brigada Morales y Molina

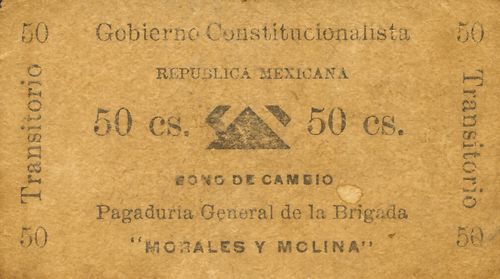

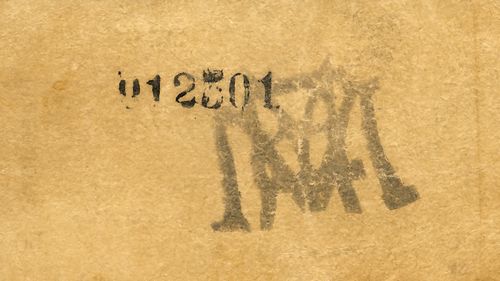

and light brown, with a slight change of type (“MORALES Y MOLINA” in quotes). This might have been on the same plate,

M1886 50c Brigada Morales y Molina

M1886 50c Brigada Morales y Molina

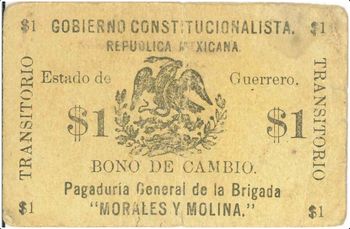

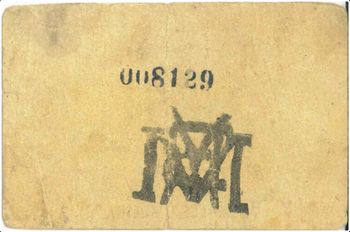

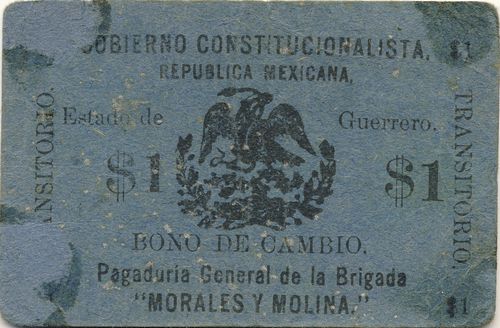

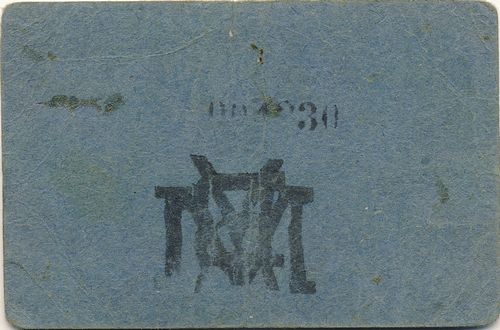

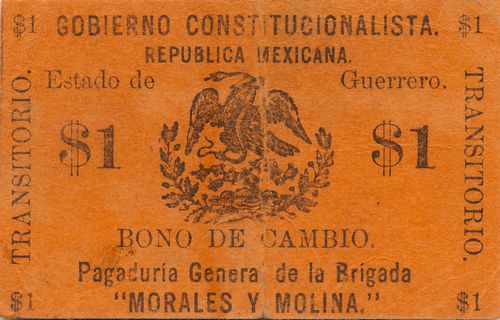

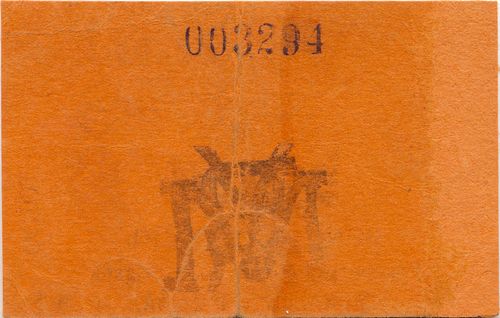

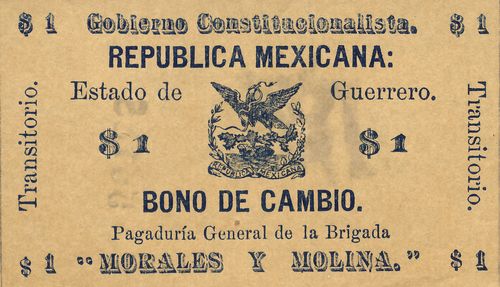

For the $1, there were three designs. The first shared its design with the $5 and $10 notes and is known on white, blue and orange paper.

M1887 $1 Brigada Morales y Molina

M1887 $1 Brigada Morales y Molina

M1887 $1 Brigada Morales y Molina

M1887 $1 Brigada Morales y Molina

M1887 $1 Brigada Morales y Molina

M1887 $1 Brigada Morales y Molina

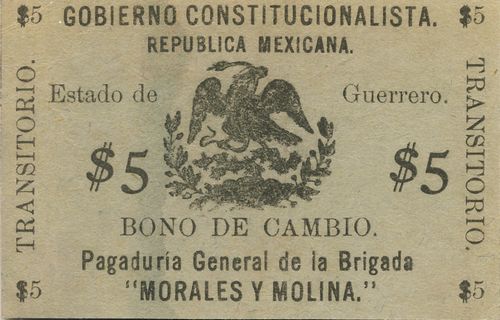

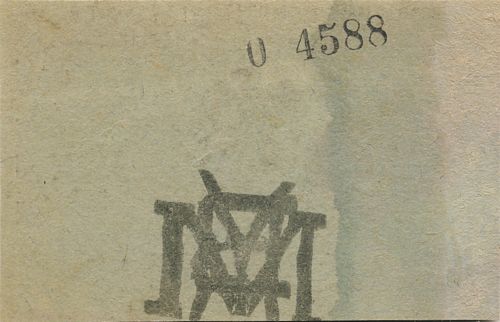

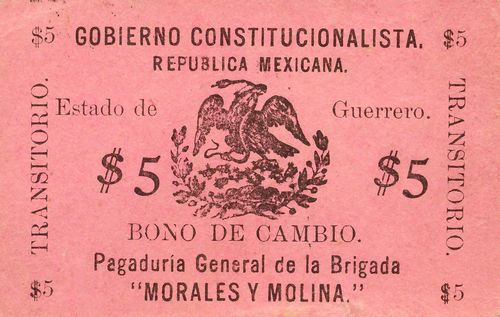

The $5 is known in grey or pink

M1890 $5 Brigada Morales y Molina

M1890 $5 Brigada Morales y Molina

M1890 $5 Brigada Morales y Molina

M1890 $5 Brigada Morales y Molina

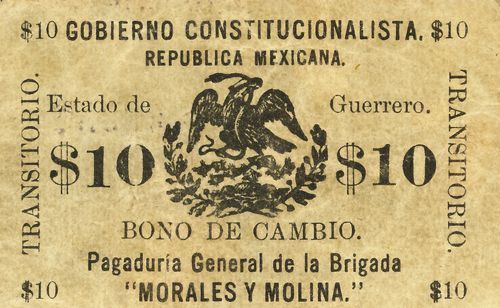

and the $10

M1891a $10 Brigada Morales y Molina

M1891a $10 Brigada Morales y Molina

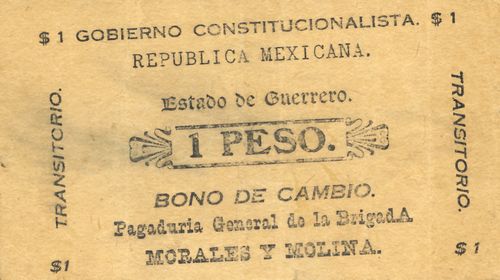

A second type of $1 has a different national emblem and typeface, but still has the monogram and number on the reverse.

M1889 $1 Brigada Morales y Molina

M1889 $1 Brigada Morales y Molina

Finally a third type has no central emblem and is signed on the reverse. Could this have been dated to after 25 May, when Robles del Campo sent Carranza the two monograms that Morales y Molina had been using to seal the paper currency that he had issued?

M1888 $1 Brigada Morales y Molina

M1888 $1 Brigada Morales y Molina

| from | to | total number |

total value |

|||

| 10c | ||||||

| 20c | ||||||

| 50c | MORALES Y MOLINA | includes numbers 004734CNBanxico #11112 to 005717CNBanxico #4375 | ||||

| "MORALES Y MOLINA" | includes numbers 000896CNBanxico #11115 to 071178CNBanxico #4379 | |||||

| $1 | includes numbers 000298CNBanxico #4392 to 008129 | |||||

| different vignette | includes numbers 051342CNBanxico #4388 to 908492CNBanxico #4383 | |||||

| no central vignette | ||||||

| $5 | includes numbers 002693CNBanxico #4394 to 004822CNBanxico #4396 | |||||

| $10 | includes number 000227CNBanxico #11116 to 000293 |

On 24 March Carranza told General Julián Blanco that these bonos were of forced circulation but he would soon send him funds so that they could be exchanged for Gobierno Constitucionalista notesCEHM, Fondo XXI-4 telegram Venustiano Carranza, Faros, Veracruz to General Julián Blanco, Dos Caminos, Guerrero, 24 March 1915.

On 11 April General Agustín Robles del Campo was appointed by the governor, Julián Blanco, as Comandante Militar in Acapulco. A few days later he wrote to Carranza that though Morales y Molina’s currency had been accepted with difficulty in the beginning, this had become impossible since Morales y Molina had left Acapulco, since people thought that the currency had been withdrawn and therefore demanded Carrancista notes. Businesses, when forced to remain open, had raised the prices of their goods, and were short of many of them since the only money used in the marketplace lacked any value outside the state and they could not purchase stock. Constitutionalist cartones and fractional coinage had disappeared leaving just Morales y Molina’s ever depreciating notes. Robles del Campo believed the only solution would be immediately to withdraw these notes, giving businesses drafts drawn on Veracruz in exchange. He added that Edmundo González Roa, who had been sent by the Secretaría de Hacienda as Visitador de Hacienda, could confirm the palpable damage that this paper money was causingCEHM, Fondo CDLXXX (Miscelánea de documentos sobre Venustiano Carranza, 1872-1922), carpeta 1, legajo 15.

There were other similar reports. On 14 April Nestor Guinto, Presidente Municipal of Aguas Blancas, Guerrero, told Carranza that the dealers in maize and other foodstuffs were refusing to accept Morales y Molina notes in spite of fines because they were unable to use them to buy further imports and people were starving. Guinto asked Carranza to order the notes to be exchanged to prevent further disorderABarragán, caja II, exp. 9, f 41. On 27 April a junta of Acapulco merchants sent a telegram (via a U. S. warship and the U. S. State Department) to Carranza that the region was suffering from a complete lack of cereals and asked him immediately to exchange the Morales y Molina bonos for notes of general circulationCEHM, Fondo XXI Venustiano Carranza, carpeta 37, legajo 4017.

On 25 May Robles del Campo wrote to Carranza that he was sending him, by separate post, two monograms that Morales y Molina had been using to seal the paper currency that he had issued. These monograms, as well as a numerator stamp and a number of blank frames (esqueletos), ready to be used for circulation, he had picked up when he took charge of the Comandancia, in order to put a stop to the issue.

Robles del Campo did not know how much had been issued but would investigate and report. Most of the issue was concentrated in Acapulco, and in practice was being redeemed by the federal offices and some businesses, as no-one was accepting it in transactions, and the troops were therefore refusing to take it in payment of wages. It was urgent to change this money in the most convenient wayCEHM, Fondo XXI Venustiano Carranza, carpeta 40 legajo 4376.

Withdrawal

So this issue ended in early April, and quickly lost favour. However, it was one of the military issues that Carranza acknowledged. On 13 July 1915 the Secretaría de Hacienda, in circular núm. 32, was allowing these notes to be deposited, and they were included amongst the twenty different military issues listed when Carranza decided to unify the currency and withdraw all such issues. On 28 April 1916 Carranza decreed that, in order not to prejudice the holders of such notes, the Tesorería General de la Nación, the Jefaturas de Hacienda and the Administraciones Principales del Timbre would receive such notes on deposit. Holders had until 30 June to hand them in and obtain a receipt. Thereafter any outstanding note would be considered null and void, and meanwhile anyone who dealt with such notes, or retained them in their possession, would be punished.

On 24 July 1916 Carranza decreed that from 1 August notes that had been deposited in accordance with the former decree would be exchanged for infalsificables at a rate of ten for one, but excepted certain issues, including these Morales y Molina notes. For these he set a new time limit for depositing them of 30 September and the manner of their redemption would be decided in the future.

Finally on 4 September 1917 Carranza decreed that, since certain individuals and businesses were still speculating with the nullified issues, it was strictly forbidden to deal in these issues.