Advertisements on Chihuahua notes - Clubs and bars (Ciudad Juárez)

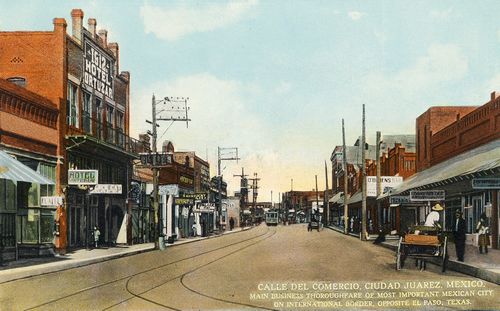

Ciudad Juárez became an adult playground even before U.S. Prohibition because Texas prohibition preceded the national program by more than nine months. On 15 April 1918, saloons in El Paso closed, and spirits, beer, and wine were no longer legally sold in the American town. The U.S. Congress passed the Volstead Act on 28 October 1919, and alcohol producers and purveyors legally were ordered to cease operation by early 1920. The effect on Ciudad Juárez, according to a reporter for the New York Herald Tribune, was a very high percent of the citizenry engaged directly or indirectly in the selling of liquor to thirsty Americans who daily crossed the Rio Grande. The proprietors of the new drinking palaces were chiefly foreigners — Spanish, French, and American — who secured prestanombres mexicanos (silent Mexican partners) to operate legally in Mexico. Juárez had two breweries, three large distilleries, and between two and three hundred better class saloons. Practically all of the city’s revenue and a good part of Chihuahua state taxes came from levies, legitimate and illegitimate, on those establishments.

Prohibition proved a major boost to Ciudad Juárez, but bars, cafés, and cabarets did not disappear when it was repealed in 1933. Like the curio trade, Juárez adjusted to changing conditions and consumer demand in the United States, but the activity pattern had become entrenched, and into the 1950s, the Mexican border town still held appeal for certain forms of adult entertainment.

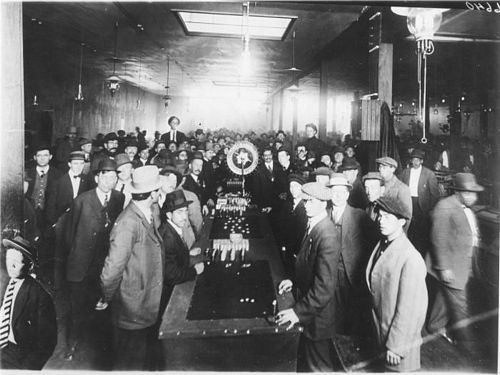

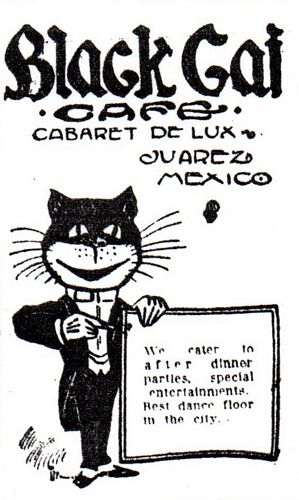

Black Cat Café

The Black Cat Café was on the ground floor of the Hotel Ortuzar, the property of the Spaniard Emiliano Ortuzar, on 16 de Septiembre near to the junction with calle Lerdo.

During the Villista era from December 1913 to December 1915 it was owned by Villa’s brother, Hipolito Villa and was a favourite of Villa himself. It was the location for one report of dealing in counterfeit currency.

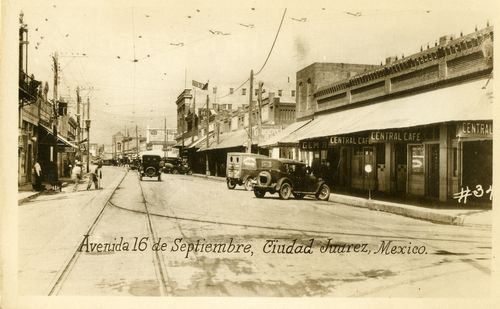

Hotel Ortuzar and Black Cat Cafe on left

Interior of the Black Cat Café (photo courtesy of Susana Reyes/Juárez de mis Recuerdos)

Later it offered a caberet de lux.

BLACK CAT CAFÉ (rubber stamp)' known on $1 dos caritas.

Central Bar And Cafe

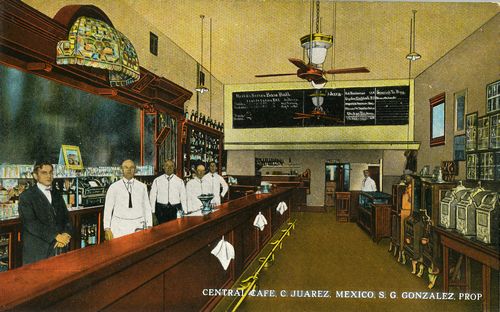

Founded in 1907, the Central Café, unlike most Prohibition era cabarets, was initially a traditional dining and entertainment venue designed to appeal to Mexican and American families. The dining room of the café was simple, tidy, and efficient, and the walls surrounding the space was covered with hand painted murals of classic Mexican scenes. The kitchen was staffed with Mexican cooks who prepared family style meals that attracted a steady clientele.

The Central Café was owned and operated by Severo G. González, a Mexican-American from El Paso who became something of a local celebrity through his enterprising accomplishments. In addition to the Central Café González was a tireless sports promoter. In 1926 he opened the New Tivoli Cockpit that would stage prize cockfights, and in the same year he partnered with other investors to build and operate the Juárez Coliseum, a twelve thousand-seat open- air sports arena for prize fights, wrestling matches, dog races, bicycle races, and track meets.

The Central Café was located at 461 16 de Septiembre at the corner with Avenida Lerdo, where the southbound streetcar turned west on to the town’s main street.

When Prohibition began to transform dining establishments in Juárez to bar- cafés and cabarets, González played right along. Like other proprietors González converted part of his establishment to a full- blown bar complete with slot machines.

In 1924, González opened the Central Café No. 2, and, unlike the original, the interior was lavishly decorated with purple draperies with gold fringe wall furnishings and satin- shade- covered table lamps surrounding a dance floor. The menu was elevated to include wild game dishes to appeal to the demands of Prohibition era diners. Additionally, the Central Café establishments— the original and No. 2— boasted the only air conditioning systems in place among Ciudad Juárez cabarets.

During the 1920s the Central Café featured live orchestral entertainment, a necessary ingredient to successful Juárez cabarets. The Central Café became an institution in Ciudad Juárez, a first-class cabaret that helped set the standard for sophisticated dining and dancing in the city. Regardless, Prohibition in the United States was repealed in 1933, and the Mexican federal government, under Lázaro Cárdenas, outlawed casino gambling in 1934. The death knell to the cabaret scene in Ciudad Juárez had sounded. Referring to the operation of the Central Café, S. G. González placed an advertisement in the El Paso Times on 27 March 1934 that said it all: “We will be open all this week, including Sunday, with the usual service, good food, and good music. Then adios”Information on this and other bars from Daniel D. Arreola, Postcards from the Chihuahua Border: Revisiting a Pictorial Past, 1900s–1950s, University of Arizona Press, 2019.

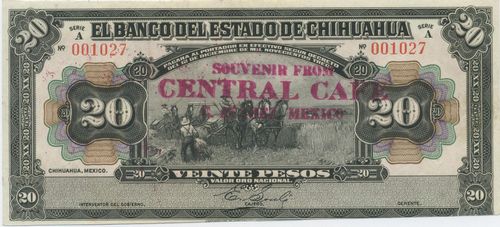

A rubber-stamped 'SOUVENIR FROM / CENTRAL CAFE / C. JUAREZ, MEXICO', known on $5, $10, $20, $50 and $100 Banco del Estado.

In 1915 González also ran a Central Bar and Cafe at 215 South Stanton Street, El Paso.

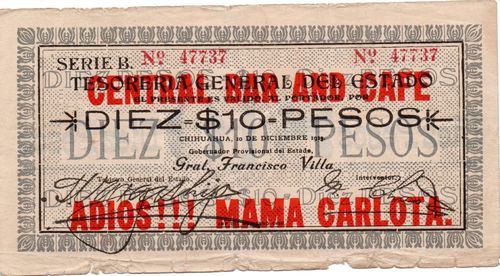

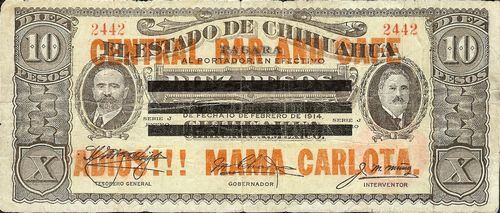

'CENTRAL BAR AND CAFE/ADIOS!!! MAMA CARLOTA. known on $10 sábanas.

'CENTRAL BAR AND CAFE/ADIOS!!! MAMA CARLOTA and three black bars', known on $10 dos caritas

We can date this overprint as on 15 September 1915 J. N. Amador wrote to Carranza from El Paso, that the Villista currency had no value, and that from that date establishments were using them as flyers. One cantina had overprinted $10 note with the words “Adiós Mama CarlotaCEHM, Fondo XXI-4, telegram Amador, El Paso to Carranza, Veracruz, 15 September 1915. The following month the Periódico Oficial of Sinaloa reported that businesses were buying notes by the kilo to use as flyers. Travellers from the United States had brought samples and in the Administración de Correos they had seen a $10 note with “Central Bar and Café, ¡¡Adiós mámá Carlota!”Periódico Oficial, Sinaloa, Tomo VI, Núm. 99, 14 October 1915.

The original “Adiós á Mamá Carlota” was a song about Maximilian’s empress, written by Vicente Riva Palacio as a parody of “Adiós Oh Patria Mia!” by the poet Rodríguez Galván.

Farewell Bar

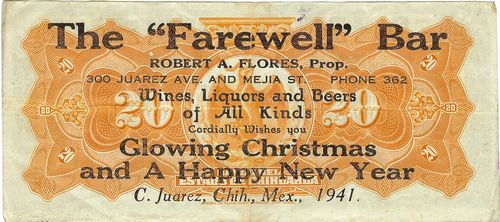

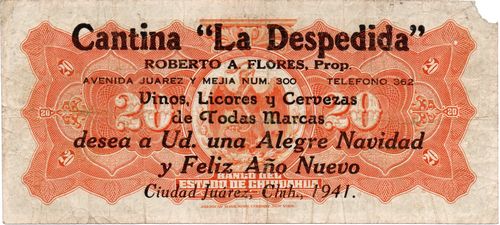

In the 1940s the Farewell Club (later known as the Café Florida Bar and Restaurant) owned by Robert M. Flores, advertised “booths for families”. These notes, in English and Spanish, are dated to Christmas 1941.

'The “Farewell” Bar/ROBERT A. FLORES, Prop./300 JUAREZ AVE. AND MEJIA ST. PHONE 362/Wines, Liquors and Beers/of All Kinds/Cordially Wishes you/Glowing Christmas/and A Happy New Year/C. Juaraz., Mex., 1941.', known on $20 Banco del Estado.

Cantina "La Despedida"/ROBERT A. FLORES, Prop./ AVENIDA JUAREZ Y MEJIA NUM. 300 / TELEFONO 362 / Vinos, Licores y Cervezas / de Todas Marcas / desea a Ud. una Alegre Navidad / y Feliz Año Nuevo / Ciudad Juárez, Chih., 1941.', known on $20 Banco del Estado.

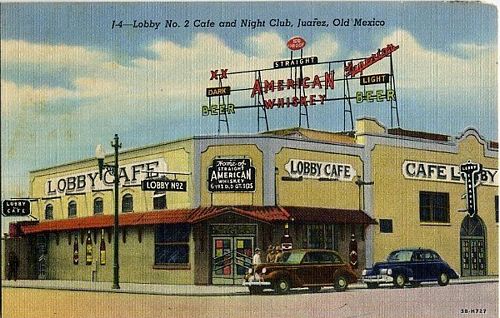

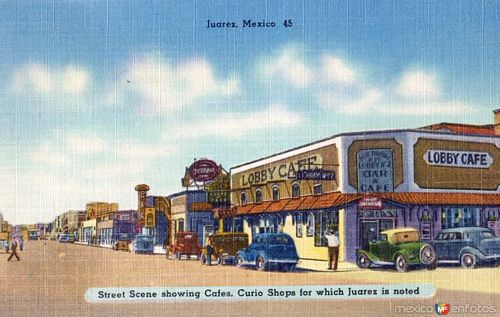

Lobby Cafe

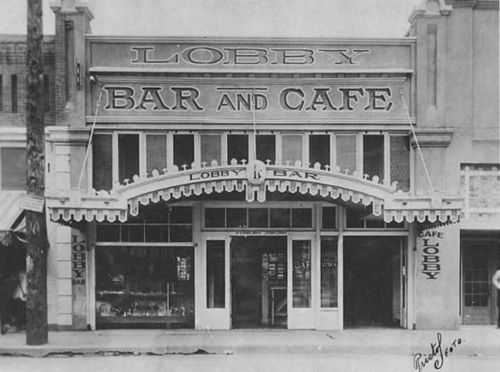

Lobby Café, first location, 1920s

The Lobby Café opened by Hugo Bonaguidi and two associates, August Lammori and Frank Dispenza, was originally located on 16 de Septiembre. The enterprise was soon relocated to Avenida Juárez, close to the international bridge, where it occupied a building previously housing the Paris Café and Bar.

At its new location, the establishment became known as the Lobby Café No. 2, and later, when ownership shifted to Fred Borland, simply the Lobby Café. The Lobby quickly gained a reputation as a first-class supper bar where a staff of thirty waiters, bus boys, bartenders, chefs, and hatcheck girls provided efficient service.

The Lobby Café No 2 under Fred Borland began to use radio station XEJ to live broadcast its orchestral entertainment.

'Souvenir / Lobby Cafe / C. Juarez, Chih., Mex.', known on $50 Banco del Estado. (This example also has a typewritten comment 'Billy Rozell-Owen 3936 S. Harvard Blvd. Los Angeles Calif.')

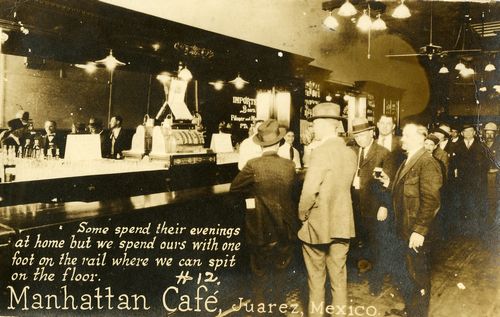

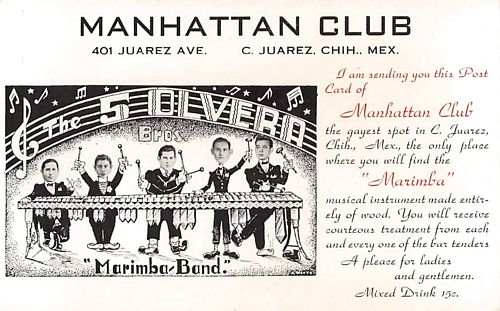

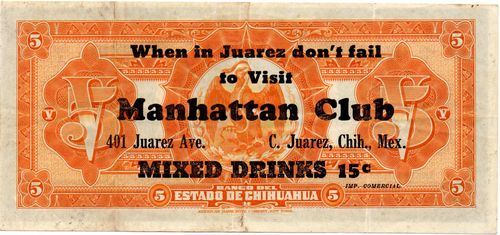

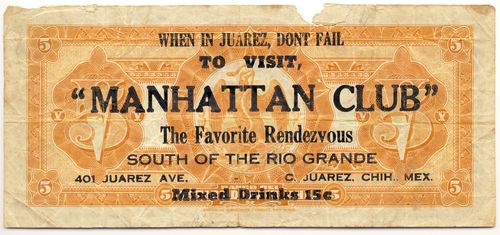

Manhattan Club

Manhatten Bar & Cafe on left

The Manhattan Cafe became the Manhattan Club, "the gayest spot in Ciudad Juárez" (when "gay" meant something else) with mixed drinks costing 15c.

'When in Juarez don’t fail/to Visit/Manhattan Club/401 Juarez Ave. C. Juarez, Chih., Mex./MIXED DRINKS 15c/IMP. COMERCIAL', known on $5 Banco del Estado

'WHEN IN JUAREZ, DON'T FAIL / TO VISIT, / "MANHATTAN CLUB" / The Favorite Rendezvous / SOUTH OF THE RIO GRANDE / 401 JUAREZ AVE. C. JUAREZ, CHIH., MEX. / Mixed Drinks 15c', known on $5 and $10 Banco del Estado

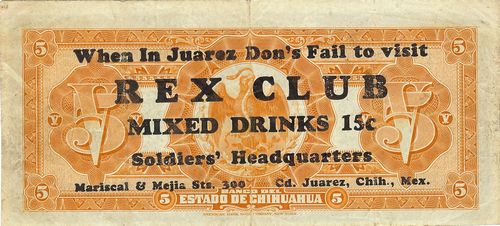

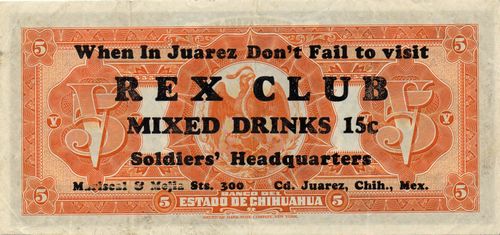

Rex Club

'When in Juarez Don’s fail to visit/REX CLUB/MIXED DRINKS 15c/Soldiers’ Headquarters/Mariscal & Mejia Sts, 300 Cd. Juarez, Chih., Mex.' known on $5 Banco del Estado

In another version the typographical error was corrected.

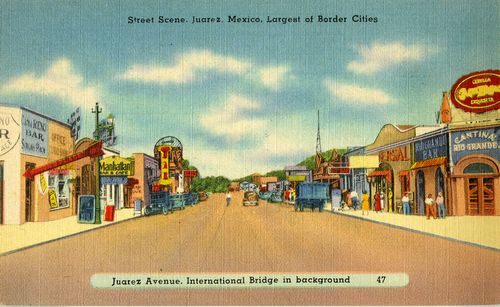

Rio Grande Bar

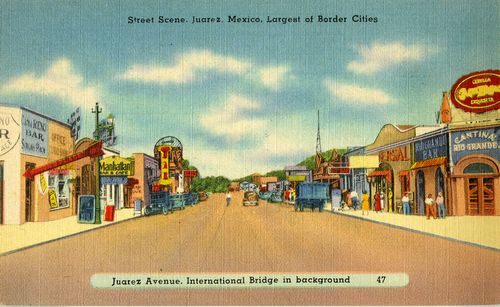

Cantina Rio Grande on right

The Rio Grande Bar & Cafe, at 418 Juárez Avenue, "two blocks from the Santa Fe Bridge", was operated by Angel González.

'SOUVENIR / RIO GRANDE BAR / CD JUAREZ CHIH, MEX', known on $5 Banco del Estado

Tommy's Place

Tommy’s Place, at 4 Juárez Avenue and owned by Tomás Sookiasian, was particularly popular with American soldiers from Fort Bliss who enjoyed the air-cooled comfort, home-cooked meals, good fellowship and range of drinks at the bar.

Tommy’s Place is one of the places that claim to have invented the margarita. The story is that, on 4 July 1942, a bartender by the name of Franciso “Pancho” Morales mistakenly created the drink after a woman ordered a magnolia. This new creation spread through the southwest and helped to speed up the importation of tequila into the States with its widespread popularity. Morales was a Juárez bartender for 21 years before immigrating to the United States in 1945 and becoming a milkman for 25 years.

'TOMMY'S PLACE/4 Juarez Avenue C. Juarez, Chih./ TOMAS SOOKIASIAN, Prop.', known on $20 Banco del Estado.