Second attempt

The first Banco de Chihuahua had stopped functioning before the Banco Mexicano appeared in early 1878La Patria, Mexico City, 23 April 1878. Confirmation of this is that the bank was not in operation in August 1883 ('There are three banking houses and you can get exchange on any city nearly in the world. There is the Bank of Mexico, the Bank of MacManus and Sons, and of Creel and Co. These last two are American, though Creel is by marriage to the daughter of Gov. Terrazas identified with the native element.' El Paso Herald, 5 August 1883) nor was it in existence on 31 July, 1882 (El Norte, 5 July 1900) but on 19 December 1883 Müller was given permission to re-establish his bank and issue the 300,000 pesos. In the same decree the bank was also given permission to circulate another 500,000 pesos, this time payable on sight in Mexican silver pesos (en pesos de plata del cuño mexicano). The first issue had to be in circulation within two months, and the second issue within eight months or the concession would lapse. Such notes as were to be issued had to carry the signature of the Administrador General de Rentas del Estado or an indication that they had been registered in a book established in his office to record numbers and denominationsPeriódico Oficial, 5 January 1884. So the bank should have issued notes within two months of December 1883 but it is not included in González’s authorisation to issue fractional currency during the nickel crisisPeriódico Oficial, 7 May 1884, had not started by July 1884Memoria de la Secretaría de Hacienda correspondiente al ejercicio fiscal de 1884 á 1885, Mexico, 1885 and is not mentioned in a newspaper article on Chihuahuan banks in August 1884El Tiempo, Mexico City, 19 August 1884.

On 23 August 1884 a newspaper reported that the Banco de Chihuahua had been granted an extension of eighteen months to the period granted to existing banks to comply with the 1884 Código de ComercioEl Foro, 23 August 1884. This was at the time that the Chihuahuan elite were lobbying against the Act and probably referred to the requirement for banks to withdraw their notes unless they subjected themselves to the Act.

Since it is inconceivable that the bank put more than 300,000 pesos into circulation (the highest amount it achieved in 1890 was $158,000) there would have been no need for another series (or overprint) with the revised legend ‘en pesos de plata del cuño mexicano’. Indeed, there does not seem to have been any notes of this first isue with the seal or some other indication of the Administrador de Rentas, as specified by the terms of the 1883 decree.

Issues

25c notes

| date of issue | date on note | series | from | to | Presidente | Contador | |

| 1875 | C | Müller | Markt |

The 25c is known only as a proof and not as an issued note.

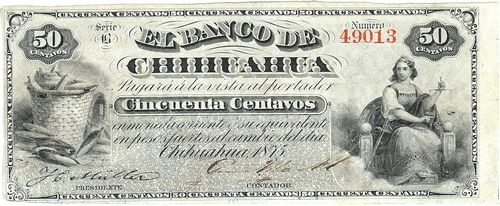

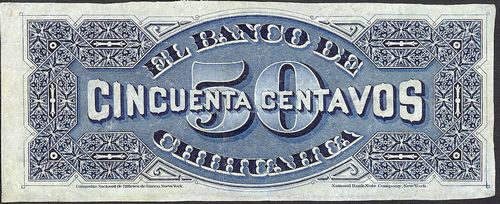

50c notes

M70a 50c Banco de Chihuahua

M70a 50c Banco de Chihuahua

| date of issue | date on note | series | from | to | Presidente | Contador | |

| 1875 | B | Müller | Markt | includes numbers 6039 to 49016A group of 50c notes bearing serial numbers 490— "were found in an envelope when some carpenters were removing the old wooden floors of the house that belonged to General Luis Terrazas, whilst twelve $1 notes survive, most of which were also in the same hoard." (Richard Long, Mexican Market Forecast, vol. 1, no. 13, 16 July 1979) |

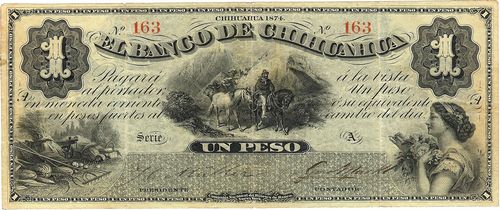

$1 notes

M71a $1 Banco de Chihuahua

M71a $1 Banco de Chihuahua

| date of issue | date on note | series | from | to | Presidente | Contador | |

| 1874 | A | 001 | Müller | Markt | includes number 163 to 73553CNBanxico #5352 |

I888 concession for El Banco de Chihuahua

On 15 December 1888, in accordance with the new federal Code, the concession for a Banco de Chihuahua was renegotiated with the Secretaría de Hacienda y Crédito Público. Lauro Carrillo represented the bank and so the application was probably from the anti-Terrazas Pacheco faction. This will have been that faction’s second attempt to acquire a bank after the failure of the first Banco Minero Chihuahuense.

As with the other concessions renegotiated at this time, the bank’s concession was limited to fifteen years. It could no longer issue notes of legal tender, payable in silver with an 8% discount and such notes as remained in the bank, or in circulation, had to be withdrawn and destroyed before 30 June 1889. The bank was given permission to issue notes payable on sight in silver coins (moneda de plata). Such notes could be in denominations of 25c, 50c, $1, $2, $5, $10, $20, $50, $100, $500 and $1,000, but only six of these values (25c, 50c, $1, $5, $10, and $20) were printed.

The contract also stated that the existing issue of silver notes (moneda de plata) was to be replaced by a new issue, with a different design and signed by the Interventor with the bank given one year to carry out the substitution. However, the concession was drafted in a standard format, so we do not have to assume that by this time the bank had in circulation both (a) notes de moneda corriente, pagaderos en plata con 8 por ciento de descuento to be withdrawn by 30 June 1889; and (b) notes de moneda de plata to be withdrawn by 15 December 1889. Only the former are known and it seems that the latter were not needed.

Once the new concession had been granted a new company was established by Carlos Pacheco, Lauro Carrillo, Félix Francisco Maceyraironic that Maceyra had criticised the original Banco de Chihuahua, Agustín Becerra, José Valenzuela and Hubert Waithman. The company’s capital was composed of ten founder shares of $50,000 each, of which 40% was paid up: Carlos Pacheco took one share; Lauro Carrillo two (one for transferring the concession); Félix Francisco Maceyra two; Agustín Becerra one; José Valenzuela one; Hubert Waithman one; Celso González one and Manuel de Herrera one. Félix Francisco Maceyra was appointed President and Celso González Accountant (Contador).

The bank was thus owned by the anti-Terrazas faction known as the circlo Pachequista. This group had the support of President Díaz and held power in Chihuahua from 1884 until 1892 with Pacheco as governor from 1884 to 1888 and Carrillo as interim governor in 1887 and constitutional governor from 1888 until 1892In the 1886 state legislature the pro-Pacheco deputies included Pedro Acosta y Ortiz, Lorenzo J. Arellano, Pedro Cabajal, Gaspar Sales, Tomás Dozal y Hermosillo, Antonio Prieto and Lauro Carrillo whilst the Terracistas included Enrique de la Garza, Felipe Acosta, Francisco A Muñoz, Leonardo Siqueros, Matías Balderrama, Gabriel Aguirre and Rómulo Jaurrieta. Other members of the group were Félix Francisco Maceyra from Chihuahua and the González and Herrera families from Guerrero who were all included in the share allotment.

The new bank began operations on 7 December 1889El Estado de Chihuahua, 14 December 1889.

American Bank Note Company print run

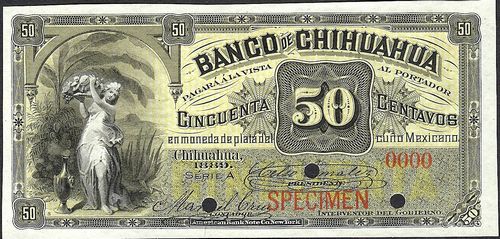

The ABNC produced the following series of notes. Again, none of the vignettes used were specific to this bank. The 25c note had a vignette of peasants (C-3730) on its face and the 50c note had a goddess (listed as Cont. #23 (103).

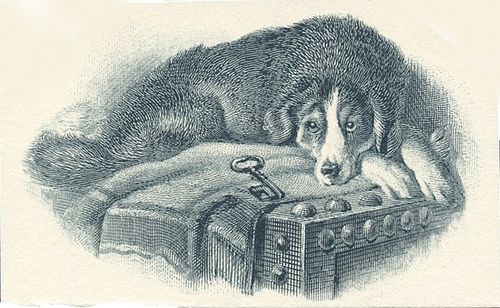

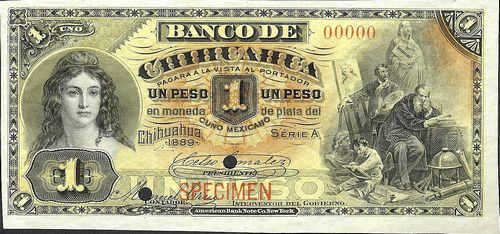

The $1 had the portrait of a goddess (ABNC #187) and a representation of the arts (ABNC #437) on the face and a dog guarding a strongbox (ABNC #333) on the reverse.

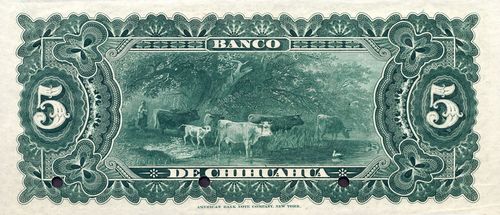

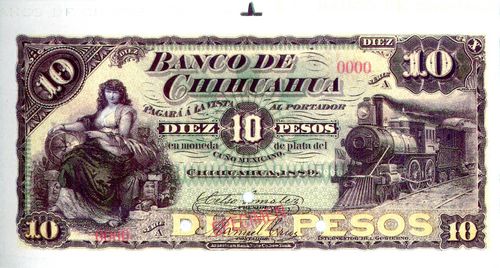

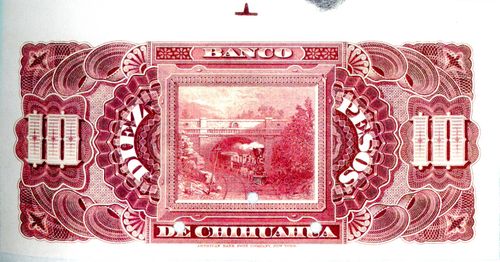

The $5 had a girl (goddess) with a basket of flowers (C-335) (similar to the reverse of the earlier $1 NBNC note) and a portrait of Athena, the goddess of wisdom, (C-152) on its face and a pastoral scene (C-172) on the reverse. The $10 had a seated goddess with shield and palm frond (C-255) and part of a vignette of a train (C-295) on the face and a vignette of a train passing under a bridge (listed as NBNC “Aqueduct”) on the reverse.

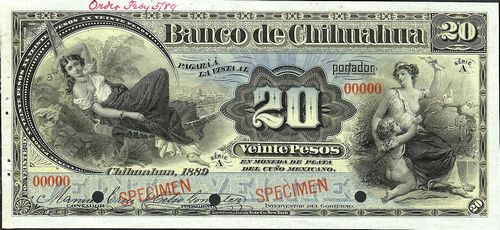

The $20 had a vignette, entitled ‘The Siesta’ (ABNC #838), which had been engraved by James Smillie James Smillie was born in Edinburgh, Scotland, on 23 November 1807. His father was a silversmith and James was fascinated from a young age by the art of engraving silver objects and soon became determined to learn the art himself, though his mother held him back for some time, saying he was far too young. But the young James, only twelve at the time, was rather persistent and so ended up being an apprentice at the Edinburgh studio of James Johnston, a well-known silver engraver. This was short-lived, due to Johnston’s sudden death, and another apprenticeship followed, this time in the studio of Edward Mitchell. This, however, was cut short as well, because in 1821, the whole family emigrated to Quebec, Canada.

James' father started his own silversmith shop in Quebec and employed James, who set to work developing his engraving skills. He soon moved from engraving names in rings, etc, to more elaborate engravings for visiting cards. Soon after, he would open his own engraving shop, together with his elder brother David. Business was booming, as the local regiment came to them for engraving their ornaments and crests. Later, father and sons would combine their shops in a better part of town, to attract more business. All the while, James developed his engraving and artistic talents. He received a number of orders for engraving various scenes.

In 1827, Smillie got the opportunity to sail to England, where he would be able to get better training as a landscape and portrait engraver. While finding no luck in London, he returned to his home town of Edinburgh where he managed to be taken in and trained by Andrew Wilson. For the first time, Smillie was able to seriously study the art of engraving and he made great strides.

After some five months, Smillie returned to Canada. After the sudden death of their father, both brothers moved to the United States in 1830, in search of better job opportunities. James’ career flourished and he became known for his quality engravings, which made the major banknote printing firms sit up and pay attention. In 1861, the National Bank Note Co hired him as Master Engraver, and he engraved vignettes for U.S. postage stamps and for bank notes.

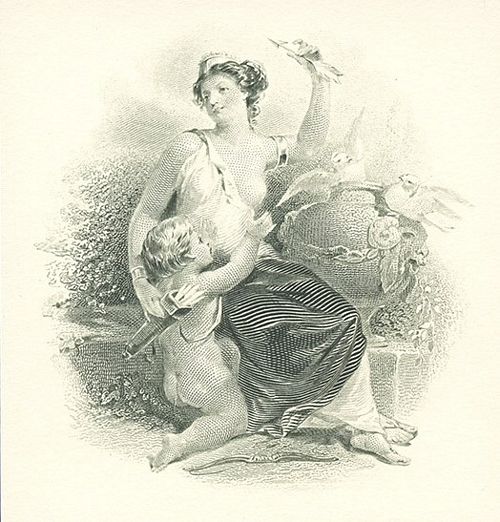

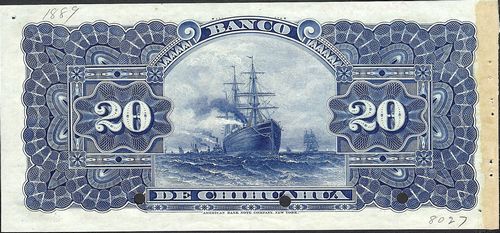

James Smillie retired in 1874 but remained active as an engraver, even doing the odd job for the American Bank Note Company. He died on 5 December 1885., and another of Cupid being disarmed by his mother, Venus, after Cupid had accidently shot his mother with an arrow, causing her to fall in love with the mortal Adonis (C-208) on the face and a ship (C-239) (really appropriate!) on the reverse.

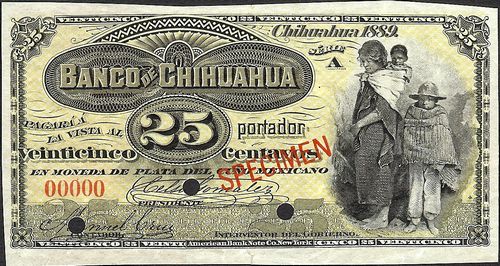

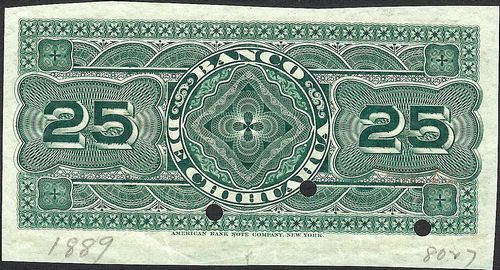

M73s 25c Banco de Chihuahua specimen

M73s 25c Banco de Chihuahua specimen

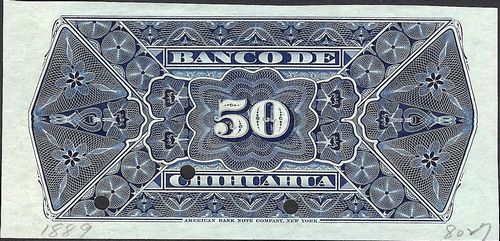

M74s 50c Banco de Chihuahua specimen

M74s 50c Banco de Chihuahua specimen

M75s $1 Banco de Chihuahua specimen

M75s $1 Banco de Chihuahua specimen

M76s $5 Banco de Chihuahua specimen

M76s $5 Banco de Chihuahua specimen

M77s $10 Banco de Chihuahua specimen

M77s $10 Banco de Chihuahua specimen

M78s $20 Banco de Chihuahua specimen

M78s $20 Banco de Chihuahua specimen

| Date | Value | Number | Series | from | to |

| February 1889 | 25c | 800,000 |

1 | 800000 | |

| 50c | 200,000 |

1 | 200000 | ||

| $1 | 100,000 |

1 | 100000 | ||

| $5 | 8,000 |

1 | 8000 | ||

| $10 | 4,000 |

1 | 4000 | ||

| $20 | 1,000 | 1 | 1000 |

American Bank Note Company records show that in February 1889 it printed a total of 500,000 pesosTwo $1 tint plates (no. 1 and 2) and $1 face and back plates (12 notes); two $5 tint plates (no. 1 and 2) and $5 face and back plates (2 notes); two $10 tint plates (no. 1 and 2) and $10 face and back plates (2 notes); and two $20 tint plates (no. 1 and 2) and $20 face and back plates (1 note) were engraved on 5 February 1889.

One 25c tint plate was engraved on 5 February 1889 and four 25c face and back plates (no. 1, 2, 3 and 4) (18 notes) were engraved on 22 April 1889.

One 50c tint plate was engraved on 5 February 1889 and four 50c face and back plates (no. 1, 2, 3 and 4) (10 notes) were engraved on 22 April 1889 (ABNC, folder 1529, Banco de Chihuahua (1931-1931))., but highest known numbers and the total value of notes in circulation at any one time suggest far less were issued, and in fact $300,000 in unissued notes were burnt when the bank failedCEHM, Colección José Y. Limantour, carpeta 50, legajo 13399, letter José Valenzuela to Limantour, 10 July 1896.

The 25c and 50c issued notes have a small control number in the left bottomhand (50c) or right bottomhand corner (25c). The number is either no number, 2, 3 or 4 and refer to the four different plates (of either 18 25c notes or 10 50c notes) that the ABNC produced.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The American Bank Note Company produced specimens of the 25c and 50c notes with a lighter background in July 1889 but these did not gain approvalABNC, folder 1529, Banco de Chihuahua (1931-1931).

Signatures

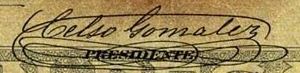

The notes carry the printed signatures of Celso González as President and Manuel Cruz as Accountant (Contador) and the hand signature of Miguel Ahumada as Interventor.

|

González was in charge of collecting taxes (recaudador de rentas) in 1867 and a deputy to the local Congress on five occasions. He was substitute governor from 9 April to 3 October 1884 and had to deal with the nickel coinage crisis. Then when the federal Código de Comercio came into force, he had to direct efforts to ensure that the local banks maintained their concessions. Later he was twice substitute governor for Lauro Carrillo. González’s fortunes deteriorated in the 1890s, by which time the Terrazas had taken over the Banco de Chihuahua. Without their own access to credit the Guerrero undertakings could not survive the financial depression. González himself obtained a loan from Enrique Creel for 200,000 pesos but by the time of his death, in 1897, the loan had not been repaid and as a result Creel took over all the estates that González had built up during the 1880s and 1890s and had had to pledge as securityEl Correo, 24 May 1903. |

|

|

Manuel Cruz: He was already contador in December 1889 and held the post until October 1891. Born in 1848, he served as deputy and jefe político of Matamoros. In this role he raised the Guardia Nacional to fight the Porfiristas in 1876 and defeated them at Piedras Verdes. He died in Mexico City in 1898. |

|

|

Ahumada was in charge of the tax service (Jefe de la Gendarmería Fiscal) in Chihuahua in 1892 when Díaz chose him as the compromise candidate for the governorship to settle the political infighting between the Terrazas and Carrillo cliques. He was governor from 1892 until 1904 though he renounced the post in 1903 when he was elected governor of Jalisco, winning reelection until January 1911. During the Maderista revolt in 1911, Díaz once again called upon him to take over the governorship of Chihuahua but this time his influence and prestige were unable to deflect the revolution and he handed over the reins to Abraham González on 10 June. In 1913, he was a deputy in the 9th district of Jalisco in the legislative chamber called up by President Huerta. He was the President of the Chamber of Deputies in 1914. He emigrated to El Paso, Texas and died there on 27 August 1916. |

|

Other personnel

Other people associated with the bank included:

| Agustín Becerra was a founding shareholder. | |

| Mauro Candano was contador from November 1891 until February 1895. Born in 1855, Candano had both a military and political career. He married Aurelia González from Guerrero and was a member of the Carrillo faction, serving as interim governor for Lauro Carrillo in 1889. From 1891 until 1895 he was contador of the Banco de Chihuahua and then in 1896 was contador of the Banco MejicanoFrancisco Almada, Gobernadores de Chihuahua, Chihuahua, 1980 but is he confusing this with the Banco de Chihuahua? but went to Mexico City in 1897. He later returned to Chihuahua, took part in the Ciudadela coup in 1913 and thereafter supported Huerta (though he interceded on behalf of some of the regime's victims). He died in 1938. | |

Lauro Carrillo was born at Sahuaripa, Sonora on 2 April 1849 though his family soon moved to Morís, Chihuahua. He worked in mining, and was elected to the state legislature in 1879. He served several terms as deputy or senator, and was substitute governor for General Pacheco in 1887, and constitutional governor in 1888. However, he was opposed by the Terrazas and blamed for mishandling the peasant rebellion at Tomóchic and in 1892 President Díaz replaced him with the compromise candidate, Ahumada. He died in El Paso on 6 March 1910. Lauro Carrillo was born at Sahuaripa, Sonora on 2 April 1849 though his family soon moved to Morís, Chihuahua. He worked in mining, and was elected to the state legislature in 1879. He served several terms as deputy or senator, and was substitute governor for General Pacheco in 1887, and constitutional governor in 1888. However, he was opposed by the Terrazas and blamed for mishandling the peasant rebellion at Tomóchic and in 1892 President Díaz replaced him with the compromise candidate, Ahumada. He died in El Paso on 6 March 1910. |

|

Abraham González: Another member of the distinguished Guerrero family, González was a man of learning who spoke English fluently and was reasonably affluent, owning farmlands on the outskirts of Ciudad Guerrero. He served as cashier (cajero) of the bank and distinguished himself by his hard work and honesty. As a relation of Celso, he was an opponent of the Terrazas and lost his job when the latter took over the bank. To compound his difficulty, the lands he owned yielded only modest profits, while foreign corporations blocked his attempts to invest in mining. By 1910 his once promising career had ended in a series of minor jobs, including cattle buyer for an American company, in which role he met Francisco Villa. González became an advocate of reform because of his hatred of the Terrazas family as represented by the government of Enrique Creel. After Madero’s victory at Ciudad Juárez he was named interim governor and won election in 1910, though he took a sabbatical to serve as Madero’s Secretario de Gobernación. In 1912 he returned to take control in Chihuahua, but had to flee Orozco’s rebellion. He returned again after Orozco was defeated but on 22 February 1913 was arrested on Huerta’s orders, and assassinated on 7 March whilst being transported to Mexico City. Villa idolized González and put his portrait on the dos caritas. Abraham González: Another member of the distinguished Guerrero family, González was a man of learning who spoke English fluently and was reasonably affluent, owning farmlands on the outskirts of Ciudad Guerrero. He served as cashier (cajero) of the bank and distinguished himself by his hard work and honesty. As a relation of Celso, he was an opponent of the Terrazas and lost his job when the latter took over the bank. To compound his difficulty, the lands he owned yielded only modest profits, while foreign corporations blocked his attempts to invest in mining. By 1910 his once promising career had ended in a series of minor jobs, including cattle buyer for an American company, in which role he met Francisco Villa. González became an advocate of reform because of his hatred of the Terrazas family as represented by the government of Enrique Creel. After Madero’s victory at Ciudad Juárez he was named interim governor and won election in 1910, though he took a sabbatical to serve as Madero’s Secretario de Gobernación. In 1912 he returned to take control in Chihuahua, but had to flee Orozco’s rebellion. He returned again after Orozco was defeated but on 22 February 1913 was arrested on Huerta’s orders, and assassinated on 7 March whilst being transported to Mexico City. Villa idolized González and put his portrait on the dos caritas. |

|

| Jesús José González was cajero in April 1895 and contador from March 1895 until the end. | |

|

He joined the Revolution of Tuxtepec, to prevent the reelection of Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada, and upon its triumph, Porfirio Díaz appointed him as governor and military commander of Puebla, on 21 November 1876. Later he was appointed military commander and provisional governor of the State of Morelos and then elected constitutional governor of the State for the period that would end in 1881. On 10 November 1879 he was promoted to brigadier general and on the same date was appointed by Porfirio Díaz as Secretary of War and Navy, remaining in that position until the end of the presidential term on 30 November 1880. On 2 December 1880, the new president, Manuel González, appointed him governor of the Federal District and as of 27 June 1881 as Secretario de Fomento, Colonización e Industria (Secretary of Development, Colonization and Industry). As such, he oversaw the enormous material and economic development that characterized the first Díaz governments. The progress in the construction of railroads, development of agriculture, industry and the economy in general, due to the policies developed by the secretariat led to the coining at that time of the phrase "Fomento es Pacheco". In 1879 Luis Terrazas’ faction in Chihuahua had displaced the supporters of Porfirio Díaz from state power, so Pacheco stood as Díaz’ candidate in the gubernatorial elections of 1884, and, with the support of the federal government and the renown gained from his position in Development, he was elected in June and assumed office on 4 October 1884. However, he requested a license from the governorship on 9 December 1884 and returned to Mexico City where he resumed the title of the Ministry of Development. In 1887 the Terracistas group tried to regain political power in the state so on 11 June Pacheco ran in Chihuahua and resumed the governorship, defeating the Terracistas movement, but separating himself from office again on 30 July. He would not exercise the governorship again. |

|

|

José Valenzuela was a founding shareholder. Valenzuela was heir to an important mining fortune together with his brother, the poet protégé of Porfirio Díaz, Jesús E. Valenzuela, José dedicated himself to representing the economic interests of the family in the state, mainly those of the compañía deslindadora led by Jesús and others of the same type. He undertook several commercial businesses and industrialists with the main economic groups of Chihuahua, in addition to being a deputy before the local legislature on several occasions. Both brothers were dealers of a compañía deslindadora within which, among others, Celso González and Manuel de Herrera also participated. The 1884 concession was signed by the two state deputies Manuel de Herrera and José Valenzuela. Valenzuela signed the February 1892 balance sheet on behalf of the president and was made president himself in March 1896. |

|

| Huberto Waithman was a founding shareholder, Waithman was Superintendente of La Negociación Minera de Pinos Altos in August 1886. |

Failure

In May 1890 the bank’s capital was reorganised into 5,000 shares of $10 eachDiario del Hogar, 14 May 1890. In November 1890 Carrillo, then Governor of the state, accompanied by his administrative entourage, made a gira (political campaign trek) through the Sierra Madre. As well as campaign promises Carrillo meant to introduce the Banco de Chihuahua currency and so drive out the notes issued by the rival Banco Minero, whose Terrazas were hoping to recapture the state house in the gubernatorial elections of 1892.

Just as the Guerrero group had been unable to sustain the original Banco Minero Chihuahuense, so it ran into trouble with the Banco de Chihuahua. It was threatened by its diminishing capital and the impending Ley General de Instituciones de Crédito. By May 1896 the bank’s notes were no longer being accepted in various parts of the state, and in view of the general alarm and the threat of a catastrophic collapse, the state governor and bank manager, in agreement with the Secretaría de Hacienda and national government, asked the Banco Minero for a loan of 150,000 pesos to overcome the crisis and close the bank without the scandal and dangers of a bankruptcy. At an extraordinary meeting of the Banco Minero on 17 May 1896 it agreed to the loanAGN, Antiguos Bancos de Emisión, Actas del Banco Minero, libro 1, 28 February 1888 to 5 January 1899. A letter from the interventor, Miguel Ahumada, to Limantour, dated 27 May 1896, gives slightly different dates. Ahumada says he made his regular visit on 16 May and then an unexpected visit on 23 May. Caught unaware, the bank was unable to show that it had the required funds to back up its notes, so Ahumada warned the directors of their responsibilities, and arranged the liquidation and takeover (CEHM, Colección José Y. Limantour, carpeta 1, legajo 176). The Banco de Chihuahua went into voluntary liquidation on 4 July 1896 with the Banco Minero in charge of redeeming the notes still in circulation, a total of some 99,577 pesos.

The National Bank Note Company and American Bank Note Company plates were cancelled by the American Bank Note Company on 18 February 1932ABNC, folder 1529, Banco de Chihuahua (1931-1931).