Second concession for El Banco de Santa Eulalia

By 1882 Francisco MacManus may have withdrawn from active involvement in the bank as on 31 July 1882 his sons, Tomás and Ignacio, and son-in-law, Scott, were given permission to issue an additional 100,000 pesos in notes of one, five and ten pesos, payable in silver pesos at par (pagaderos á la vista por pesos fuertes de plata). The notes now had to be backed by mortgages over property and registered by the Administrador de Rentas, the government had the right to appoint Interventors, and the bank had to grant the government a credit facilityPeriódico Oficial, 5 August 1882. The family was at this time very affluent as this salutary tale attests.

"A Dearly Bought Lesson.

Yesterday, a young man giving his name as McManus, called on Jefferson Reynolds, president of the National bank of this city, and asked for assistance. He said that his father was proprietor of a private bank at Chihuahua. Some time ago he was given a large sum of money by his father and started with his sister for St. Louis, where she was to attend school. They reached the city about two weeks ago, and after enjoying the sights presented by Chicago’s rival, he started on his return. In an evil moment Satan whispered in his ear that he stop at Santa Fe. Satan was wrong, but McManus did not know it. He stopped at Santa Fe. He also stopped at several gambling dives. At one of these places he met a fair damsel, who induced him to go to her Palace, up a long, dark alley, and there with the tertio-millenial [the Tertio-Millenial Exposition] full in sight, she robbed him of $3,500.

The story was found to be true and the young man started on his way home yesterday afternoon, fully equipped with a first-class ticket. It is to be supposed that Mr. McManus will skip Santa Fe when he goes to St. Louis again." (Las Vegas Daily Gazette, 8 February 1883). The designs of the five and ten pesos notes (the most uncomfortable members of the series with the ten pesos covered with a motley of disparate typefacesA personal view. El Paso Daily Times, 22 April 1883 says of the $5 note "the light and shade, the drapery, the blending of the colours and tints, are done in a rare harmony. All in all, the design and the artist's, engraver's and printer's work are not excelled by any bank notes in existence") were approved in October 1882 (the reverse of the $10 was proofed in blue and in brown) and the notes issued on 18 April 1883, thirty thousand pesos’ worth being issued in the first two daysEl Paso Daily Times, 22 April 1883. These $5 and $10 notes were hand signed.

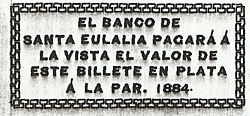

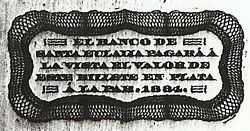

The bank had the American Bank Note Company make up two different overprints with the legend ‘EL BANCO DE SANTA EULALIA PAGARA A LA VISTA EL VALOR DE ESTE BILLETE EN PLATA A LA PAR. 1884’ to be used for ‘overprinting all notes of this issue’. This overprint would have been applied to any 25c, 50c or $1 note issued over and above the first 100,000 pesos in accordance with this additional concession but as it is probable that the bank never had more than this amount of notes in circulation at any one time it would not have required the overprints.

Also by 1883 the bank had established a branch in Parral under the management of Adolfo IwonskyEl Paso Daily Times, 4 May 1883.

1884 nickel crisis

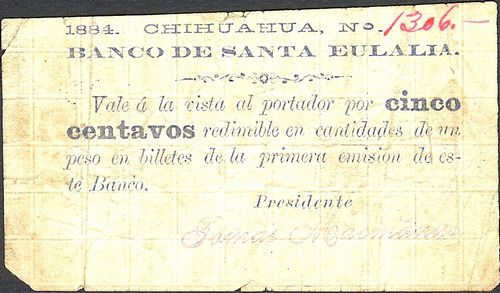

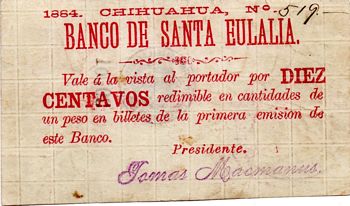

In 1884 Mexican President Manuel González attempted to introduce a new nickel coinage but this was immediately rejected by the population. On 14 April there were riots in Chihuahua as shopkeepers refused to accept the coins and since there were no other acceptable low value coins in circulation the general public were unable to purchase essential goods. To deal with the crisis Interim Governor Celso González ordered 4,400 pesos in copper coins from the Secretaría de Hacienda and also granted each of the four banks in Chihuahua permission to issue fractional paper currency in one, five and ten centavos values up to the amount of 5,000 pesosInforme of Governor Celso González, 1 June 1884.

For the Banco de Santa Eulalia only the two higher values are known, payable on sight in multiples of one peso (vale a la vista al portador en cantidades de un peso en billetes de la primera emisión de este Banco) and it is possible that the one centavo note was never produced.

M158 5c Banco de Santa Eulalia

M158 5c Banco de Santa Eulalia

M159 10c Banco de Santa Eulalia

M159 10c Banco de Santa Eulalia

On 23 March 1886 the Secretario de Hacienda, Manuel Dublán, signed an agreement[text needed] with Carlos Pacheco, representing the banks of Chihuahua, José del Collado, a director of the Banco Nacional de México, and Ramón Uzandizaga, manager of the Chihuahua branch. In it they recognized that the Chihuahuan banks had been established by concessions from the state Congress, at a time when federal control was unclear, and so the Secretaría de Hacienda confirmed the Banco de Santa Eulalia’s concession for a further 25 years, and that it could issue up to $100,000 in notes of various denominations payable in copper at par or in silver at a 8% discount ot at par in hard currency (pagaderos en cobre a la par o en plata con 8% de descuento o pagaderos a la par en pesos fuertes)AHBanamex, Actas del Consejo de Administración, 23 March 1886, folios 246-250.

Withdrawal of notes

On 13 October 1888 the Secretaría de Hacienda gave the Banco de Santa Eulalia six months to call in their notes. The bank’s directors had to produce a list of the notes in circulation within two weeks, and make public announcements of their intention to withdraw their notes. They then had to give a weekly report to the Secretaría of the number of notes cancelled.

On 22 October 1888, in response to a request by the bank’s president, Tomás Macmanus, the date on which to begin withdrawing its notes was put back to 1 January 1889: this was then postponed again until 1 March, and finally to 1 April, by which time the bank had negotiated the contract for the new Banco Comercial.

Incinerations

The Secretaria de Hacienda admitted that it did not know how many notes the bank had issuedMemoria de la Secretaría de Hacienda correspondiente al ejercicio fiscal de 1884 á 1885, Mexico, 1885.

Under the terms of the concession for the new Banco Comercial, all the Banco de Santa Eulalia notes were withdrawn and burnt. On 30 November 1889 $56,500 in notes were incinerated in front of the Administrador de Rentas del Estadooficio núm. 13 of Interventor Ahumada, 8 January 1892 in Memoria de las Instituciones de Crédito correspondiente a los años de 1897, 1898, y 1899: on 27 September 1890 $108,000 were destroyed in the presence of Miguel Ahumada, the InterventorA newspaper reported that on 12 September 1890 $60,000 had been incinerated, and the bank expected that all their old notes should be destroyed by November (El Siglo Diez y Nueve, Mexico City, 17 September 1890) but these will have been included in the later $108,000 total, and finally $26,000 were destroyed on 7 January 1892, again in Ahumada’s presenceoficio núm. 13 of Interventor Ahumada, 8 January 1892 in Memoria de las Instituciones de Crédito correspondiente a los años de 1897, 1898, y 1899. This gives a total of $190,500 being destroyed. On 8 January 1892 Ahumada reported that only $8,000 to $9,000 was still outstandingibid..

On 9 June 1892 the firm of F. Macmanus é hijos asked holders of any remaining notes to present them as soon as possible at their offices at calle Ojinaga 20El Estado de Chihuahua, 11 June 1892.