Private issues in Sonora after the revolution

One of the subsidiary aims of the revolution had been to end the exploitation of workers through the tienda de raya. As the revolution was hijacked by the bourgeoisie it is not surprising that in the following decade the workers could still complain, with little redress, of being paid in bad money (mal moneda).

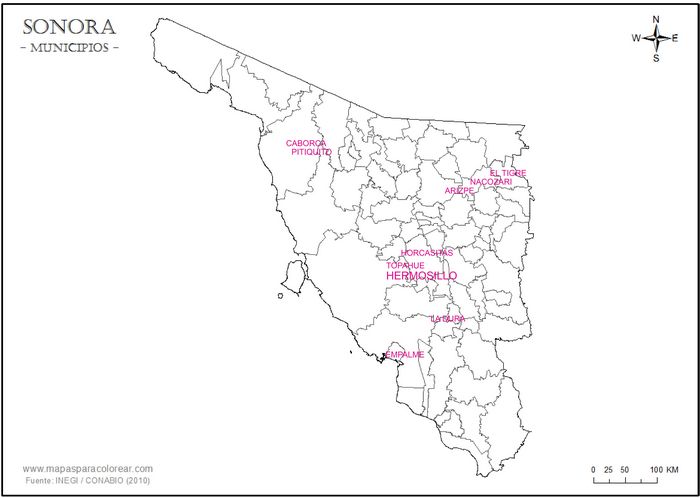

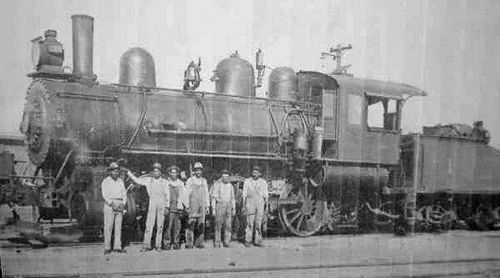

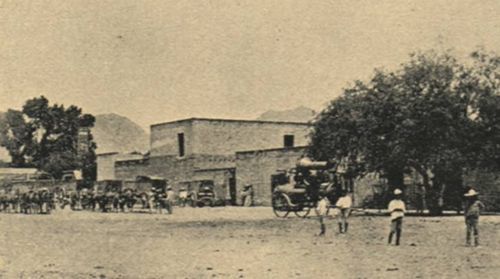

Empalme

Compañia Sud-Pacifico de México y Ferrocarril de Sonora

On 20 August 1916 employees at the workshops of the Compañia Sud-Pacifico de México y Ferrocarril de Sonora at Empalme, outside Guaymas, complained to the Governor, Adolfo de la Huerta, that the company was operating a tienda de raya, paying them only 25% in actual cash. In addition, certain items were only sold for gold. On 26 August the government exhorted the company to sell all its goods, for infalsificables, at normal prices. The company replied that it would do what it could to remove the source of complaintAGHES, Fondo Oficialidad Mayor, tomo 3083.

In March 1917 governor Adolfo de la Huerta decreed additional labour regulations, based on the recommendations of a labour council, which were compatible with those enacted in the new national constitutionprovision of a safe working environment, appointment of government safety inspectors, equal wages for natives and foreigners, hiring preferences for natives over foreigners (when qualifications were equal), foreigners' knowledge of Spanish, cash wages (as opposed to goods or tokens), and provision of medical care by Spanish-speaking physicians and pharmacists. For their part, workers were instructed to be punctual, hardworking, respectful, and obedient to company rules, including the payment of wages in cash.

Rodríguez Hermanos

Rodríguez Hermanos opened “La Mercantil”, the first store in Empalme, in December 1921 (it closed in December 1916 after 95 years of service).

In 1923 the union, the Sindicato Obrero, complained that the casa comercial of Rodríguez Hermanos, in Empalme was nothing more than the tienda de raya of the railway company Ferrocarril Sud Pacifico de México. The store gave the railway company coupons (cupones)[image needed] with which to pay their workers, the coupons only being acceptable for merchandise in the Rodríguez’ store. Since the Rodríguez never gave cash for their coupons if a worker needed money he had to sell them to a third party for less than half their value. The store was also accused of discounting coupons used for any purchase in excess of ten pesos. After an enquiry it was decided that the company was in fact giving advances on wages while the Rodríguez were offering credit facilities to individual workers and the coupons were merely a convenient method of proving that an employee was owed wages by the railway company. As the company was not in fact paying its workers with the coupons but merely giving them advances (cartas de crédito), and as, on the other hand, the store had no connection with the railway company and was not using the scrip to pay its own workers, neither party was breaking the lawAGHES, Fondo Oficialidad Mayor, no reference.

San José de Gracía

Hacienda 'Topahui'

The Hacienda ‘Topahui’ was situated forty kilometres northeast of Hermosillo and had been in the Gándara family for many years. In the nineteenth century it had paid in tokensAGHES, Fondo Oficialidad Mayor, no reference. Now, in January 1923 the local union, the Sindicato Laborista de Sonora, complained that Antonio Gándara was paying his workers with vales. These were cardboard tokens, measuring 88 x 49mm, for 10c and 25c, with the inscription

HACIENDA ‘TOPAHUI’

COMPROBANTE DE HABER

0-25

NO ES NEGOCIABLE’[image needed].

The estate was fined fifty pesosAGHES, Fondo Oficialidad Mayor, no reference.

In October 1925 it was reported that the Hacienda de Topahue used a system of boletos carrying forward any credit or debit every Sunday. If necessary, the hacienda would give workers vales drawn on one or other casa comercial in HermosilloAGHES, Fondo Oficialidad Mayor, tomo 3749, report of Comisario de Policia, San José de Gracía, 3 November 1925.

[ ]

In October 1925 some farming companies in San José de Gracía paid in vales provisionales, paying in cash when workers asked for itAGHES, Fondo Oficialidad Mayor, tomo 3479, report of Comisario de Policía, San José de Gracia, 20 October 1925. The government asked for clarification as to how frequently the workers were paid and whether the vales were redeemed in full.

Hermosillo

Hacienda 'El Molino de Camou'

The Hacienda 'El Molino de Camou', of more than a thousand hectares, was situated off the Hermosillo-Ures road, 35 kilometres from the capital. It was owned by the powerful casa bancaria "Heredos de Camou" and in 1905 was administered and managed by Alberto Camou who was a progressive farmer who tried to introduce the most modern systems of agriculture and machinery. The hacienda produced wheat, corn, beans sugarcane and, on a small-scale, vegetables and bred cattle. The wheat was turned into flour in the hacienda’s own mill.

In 1925 the Sindicato Laborista de Sonora also complained that the hacienda was paying with stamped cards (boletos sellados) usable only at the exorbitantly priced tienda de rayaAGHES, Fondo Oficialidad Mayor, no reference.

La Dura

La Dura Mill and Mining Company

In July 1923 Ricardo Clayton, the undermanager (sub-gerente) of the mining company in La Dura (who was also conveniently the local chief of police and owner of a grocery and clothing store) was also accused of running a tienda de raya. Clayton closed his accounts at the end of each month but in the meantime gave the staff hand-written chits (vales) with a blue oval handstamp ‘JORGE CLAYTON/LA DURA, SONORA and date’, a signature and value. The vales were never for more than 50c, apparently to discourage others from accepting them. As a result of the complaints Clayton suspended the use of vales and began to pay every tenth day with bank cheques that were accepted throughout the town as cash. Although the workers wanted to continue this practice the government would not allow it and instructed Clayton to pay in real cashAGHES, Fondo Oficialidad Mayor, no reference.

On 21 January 1925 small shopkeepers in La Dura wrote to R. I. Clayton (presumably Ricardo), manager of the La Dura Mill and Mining Company, telling him that they had asked the government to make him settle wages weekly rather than once a month, as under the present system workers were unable to shop where it best suited themAGHES, Fondo Oficialidad Mayor, tomo 3749. In March 1925 it was reported that the company was giving daily and exclusively to the local branch of Rademacher Muller y Cia., Sucs. a list of workers and their respective earnings so that the shop could grant them credit and that this was tantamount to running a tienda de raya. The accusation was denied though as it does not seem to have involved any paper it need not detain usAGHES, Fondo Oficialidad Mayor, no reference.

Pitiquito

Compañía Palo Verde Cotton Investment

The Palo Verde Cotton Investment Company, headquarted in Oaxland, California, owned a big cotton project in Pitiquito, in the Altar District. J. H. Harrison was the company’s manager and Charles V. Fowler the assistant manager and secretary

In 1923 the company cultivated between 1,000 and 1,200 acres of its own cotton and also helped to finance the growing of about 500 acres owned by other residents. In October of that year it opened a new $15,000 cotton gin, the first up to date gin ever erected in SonoraThe Border Vidette, 13 October 1923.

In September 1923 there was a complaint that the company paid with tickets that were only accepted by Manuel Lamas, the owner of the largest store in the area. These tickets were not true currency as they were made out to individual workers. They measured 119 x 67mm, and were inscribed 'PALO VERDE COTTON INVESTMENT CO. / No_____ / Pitiquito (date)_ / Number_____ / Labor_____ / Peso____ / Importe____ / Pesador_____’AGHES, Fondo Oficialidad Mayor, no reference.

Horcasitas

Lavin y Gómez

In September 1924 it was reported that the business house of Lavin y Gómez and another American store in Horcasitas were paying in slips and tokens (boletos y fichas) but on investigation this was deniedAGHES, Fondo Oficialidad Mayor, no reference.

Genaro Gómez and Vidal Lavín A. who established the company, Lavín y Goméz, were involved in agriculture, cattle-rearing, and industry. Their 500-hectare Hacienda de Codórachi, about thity-five miles northeast of Hermosillo and next to Estación Pesqueira on the Ferrocarril Sud-Pacífico de México, produced wheat, maize, beans and cotton and there they opened the “El Fénix” grain mill to produce the finest flour.

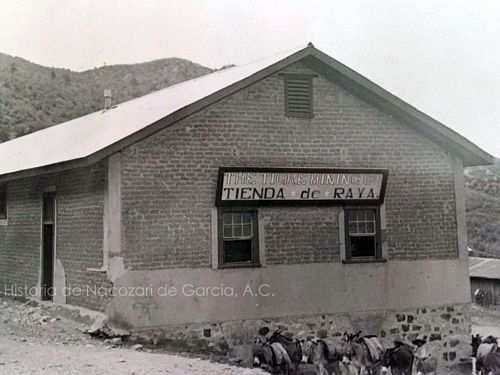

El Tigre

El Tigre Mining Company

In 1925 the El Tigre Mining Company had two tiendas de raya, at El Molino, the site of the concentration plant, and in El Tigre itself, which used a system of carteras, and only on the rare occasions when a worker was in credit on pay day, did they pay out in cash. The back of the carteras had the legend ‘No es transferible, Ni Negociable’ but whilst they could only be cashed by the named person, they could be redeemed for merchandise by any one. They could also be used in the company’s billiards halls, cinemas and wholesalers. In addition, Chinese and Japanese merchants accepted them, and redeemed them with the company at a 10% (or greater) discount. In response the government ordered the company to pay weeklyAGHES, Fondo Oficialidad Mayor, tomo 3749, report of Presidente Municipal, El Tigre, 17 August 1925: reply of Secretario, 25 August 1925.

Nacozari

Moctezuma Copper Company

In October 1925 it was reported that though the Moctezuma Copper Company did pay in cash, it gave carteras to workers who asked for them and these entitled the holders to lower prices for basic items. For instance, the company store sold flour at the local cash price of $3.60, but at $3.00 in carteras, and frijoles for 50 to 60 centavos cash, but 35c in carterasAGHES, Fondo Oficialidad Mayor, tomo 3749, report of Presidente Municipal, Pilares de Nacozari, 12 October 1925.

Arizpe

[ ]

In October 1925 the Comisario de Policia in Sinoquipe reported that there were no tiendas but that one mining company paid in cheques that were cashed by local storekeepersAGHES, Fondo Oficialidad Mayor, tomo 3749, report of Comisario de Policía, Sinoquipe, Arizpe, 20 October 1925.

Caborca

Pintas Mines Company

In October 1925 in Caborca the Pintas Mines Company paid with cheques drawn on the First National Bank of Nogales, Arizona, which were cashed at a discount in a kind of tienda de raya, established under the name of ‘Armando Quiroz’AGHES, Fondo Oficialidad Mayor, tomo 3749, report of Presidente Municipal, Caborca, 13 October 1925.

Remigio V. Aguilar

Antonio Martínez hijo

In addition the local farm owners, Remigio V. Aguilar and Antonio Martínez hijo, paid their labourers with chits for the local stores, so most were paid in merchadiseibid..

Octotober 1925 reports

On 5 October 1925 the state government sent a circular (núm. 293) to Presidentes Municipales, reminding them that Article 123 of the Federal Constitution stipulated that wages had to be paid in legal tender. Since the governor was aware that certain agricultural and mining concerns were paying in merchandise or by means of vales, fiches o cartones, he asked for a report from each Presidente Municipal of the state of affairs in their area. Many (Bavispe, Cumpas, Guaymas, Hacienda de San Rafael, Huasabas, La Mesita de Cuajari, La Misa, Nacozari Chico, Navojoa, Pilares de Teras, Sahuaripa, Santa Ana, Tubutama, Ures) reported that there were no abuses in their districts, but others mentioned instances of tiendas, as mentioned above and follows:

Though the Moctezuma Copper Company did pay in cash, it gave carteras to workers who asked for them and these entitled the holders to lower prices for basic items. For instance, the company store sold flour at the local cash price of $3.60, but at $3.00 in carteras, and frijoles for 50 to 60 centavos cash, but 35c in carterasAGHES, Fondo Oficialidad Mayor, tomo 3749, report of Presidente Municipal, Pilares de Nacozari, 12 October 1925.

In El Tigre the Tigre Mining Company was the only company still paying part of its salaries in merchandise, through its system of carterasAGHES, Fondo Oficialidad Mayor, tomo 3749, report of Presidente Municipal, Villa El Tigre, 13 October 1925.

In San José de Gracia farming companies paid in vales provisionales, paying in cash when workers asked for itAGHES, Fondo Oficialidad Mayor, tomo 3479, report of Comisario de Policía, San José de Gracia, 20 October 1925. The government asked for clarification as to how frequently the workers were paid and whether the vales were redeemed in full.

The Comisario de Policia in Sinoquipe reported that there were no tiendas but that one mining company paid in cheques that were cashed by local storekeepersAGHES, Fondo Oficialidad Mayor, tomo 3749, report of Comisario de Policía, Sinoquipe, Arizpe, 20 October 1925.

In Caborca the Pintas Mines Company paid with cheques drawn on the First National Bank of Nogales, Arizona, which were cashed at a discount in a kind of tienda de raya, established under the name of ‘Armando Quiroz’. In addition the local farm owners, Remigio V. Aguilar and Antonio Martínez hijo, paid their labourers with chits for the local stores, so most was paid in merchadiseAGHES, Fondo Oficialidad Mayor, tomo 3749, report of Presidente Municipal, Caborca, 13 October 1925.

The Hacienda de Topahue used a system of boletos carrying forward any credit or debit every Sunday. If necessary, the hacienda would give workers vales drawn on one or other casa comercial in HermosilloAGHES, Fondo Oficialidad Mayor, tomo 3749, report of Comisario de Policia, San José de García, 3 November 1925.