Salvador Alvarado

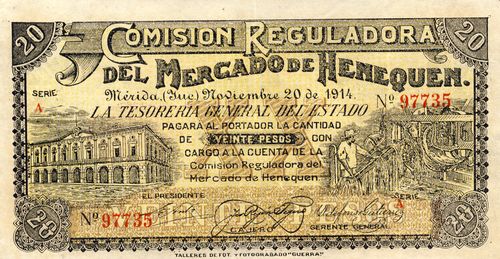

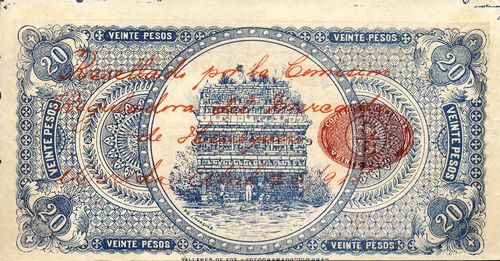

As governor, Alvarado took over the presidency of the Comisión Reguladora. Having nullified Argumedo’s $20 notes, he arranged for the others (Series A and B) to be revalidated with a seal on the face and the legend ‘Resellado por la Comisión Reguladora del Mercado de Henequen Mérida Abril 25/915’ on the reverse. Note that 25 April is a month after 25 May, when Alvarado, in his decree núm. 7, gave people thirty days to hand in the invalidated notes.

M4159e 20c Comisión Reguladora resellado

M4159e 20c Comisión Reguladora resellado

Alvarado was more “revolutionary” in abolishing the henequeneros’ use of corporal punishment, debt peonage, and slave labour, and in his reactivation of the Comisión Reguladora in November 1915. The revived Comisión Reguladora became the new worry for cordage interests and the U.S. government, especially during World War I.

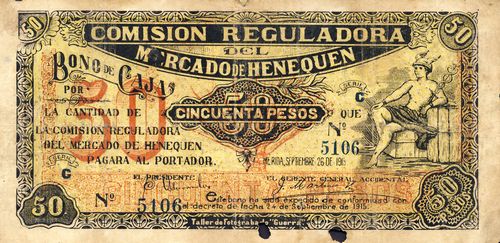

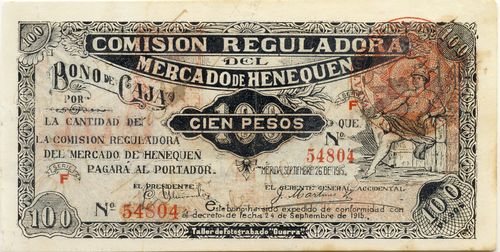

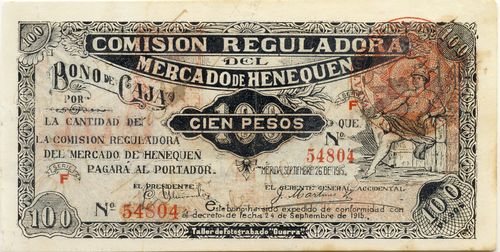

On 24 September 1915 Alvarado decreed that since the Comisión Reguladora had sufficient resources to guarantee the notes that it had issued and needed extra funds to protect henequen producers, he, with Carranza’s explicit authorisation, was authorising a futher issue of Bonos de Caja pagaderos al portador, to the sum of $15,000,000 (100,000 $50 and 100,000 $100 notes). These were now to the Comisión Reguladora’s, not the Tesorería General’s, account.

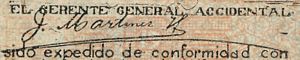

These were to be signed by the Governor and the Gerente de la Comisión Reguladora. They were signed by Alvardo and J. Martínez G. as acting general manager (Gerente General Accidental).

|

He recrossed into Mexico to join the revolution in 1911 and steadily climbed the military ranks from Major to General. He fought with Huerta against Orozco but when Huerta seized the presidency Alvarado joined Carranza, who promoted him to Brigadier General and Commander of the Army of the Southeast. On 27 February 1915, Carranza named Alvarado Governor and military commander of Yucatán. His forces had little difficulty in putting down the rebel movement and by 19 March 1915 Alvarado had arrived in the capital of Mérida. Alvarado claimed that he had passed over 1,000 decrees during his three-year tenure as governor, with an emphasis on social, education and legal reforms and freeing the Maya from debt servitude. He cancelled their indenture debts with the landowners and established laws for women and child labourers, including domestic workers, defining maximum hours, minimum pay, mandatory rest periods, health and safety standards, and prohibitions on immoral employment. His vision was to change the almost feudal hacienda system into a capitalist system converting the peones into true proletarian workers who were paid wages and in turn would increase production for the henequen plantation owners. In 1917, Carranza appointed Alvarado Chief of Military Operations for Southeast Mexico, which required that Alvarado spend many months away from Mérida. In November 1918, Alvarado was permanently recalled by Carranza. Alvarado, along with Adolfo de la Huerta, Alvaro Obregón, Plutarco Elías Calles and Benjamín G. Hill, was part of the Sonora faction that became disillusioned with Carranza. In 1919 he founded a newspaper, El Heraldo de México, which he used as a platform to discuss intellectual ideals. These political activities angered Carranza, who had him arrested. He was released in January 1920 and exiled to the United States. Returning from exile, Alvarado joined Obregón's Plan of Agua Prieta in April 1920. Following Carranza's assassination and Adolfo de la Huerta's election as the Interim President of Mexico on 1 June 1920, Alvarado was named Secretary of the Treasury. De la Huerta had inherited an almost bankrupt government, and Alvarado made numerous trips to New York City to secure funds through both loans and publicity of Yucatecan henequen. In 1921 Alvarado left the Treasury and in 1923 supported his childhood friend de la Huerta against Obregón. With the defeat of de la Huerta’s rebellion, Alvarado tried to flee to Canada, the United States, and then Guatemala, but was relentlessly pursued by Obregón's men. He was ambushed while fleeing from Obregón's force at El Hormiguero ranchero, between Tenosique, Tabasco and Palenque, Chiapas and was killed on 10 June 1924. |

|

|

Juan Martínez G. was named to replace Julio Rendón as gerente of the Comisión during the latter’s absence, in the first week of OctoberEl Pueblo, 5 October 1915. [if correct person] Juan Martínez became a radio engineer. During his 20-month governorship from February 1922 to December 1923 Felipe Carrillo Puerto sent Martínez to Cleveland to acquire a modern radio transmitter, so that the government could transmit official messages and spread the governor’s socialist ideas, such as land reform, promoting new farming techniques, granting women political rights, and family planning programs, to the people of Yucatán. He died in Mérida on 24 March 1969. |

|

M4162 $50 Comisión Reguladora

M4162 $50 Comisión Reguladora

M41632 $100 Comisión Reguladora

M41632 $100 Comisión Reguladora

| Series | from | to | total number |

total value |

||

| $50 | ||||||

| C | includes number 5106 | |||||

| I | includes number 75655 | |||||

| $100 | A | includes number 18116CNBanxico #12404 | ||||

| F | includes number 54804 |

Documents from the U.S. State Department suggest that an enquiry was made for these notes to be printed in the States. On 4 October the E. A. Wright Bank Note Company, of Philadephia, wrote to the Secretary of State that it had received a request from the Parsons Trading Company of New York to submit an estimate for steel engraved paper currency for the Mexican (Carranza) Government and asked whether it would be legal for them to execute the contract. The State Department replied on 13 October that it could not advise on the contractSD papers, 812.515/65. This correspondence is filed with a note referring to a report from Progreso, dated 30 September, of a proposed issue of $15,000,000 by the Regulating CommitteeSD papers, 812.515/66). Then, on 16 October Alvarado asked Carranza for permission to issue $50,000,000 (sic) in bonos de caja, which he would have printed by the American Bank Note Company in order to avoid counterfeiting. He would recall all the earlier issues (SE RECOGERÁ LO QUE ES ADMITIDO)CEHM, Fondo XXI-4 telegram Salvador Alvardo, Merida, to Carranza, Torreón, 16 October 1915.

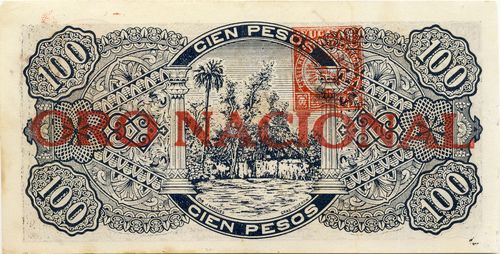

From March onwards in two decrees Alvarado ordered the Comisión Reguladora to redeem all of its paper currency. On 1 March, in consideration that the $15,000,000 in $50 and $100 notes authorised by the decree of 24 September 1915 were no longer needed, Alvarado decreed that they should be redeemed within a month. After that time the notes' circulation would be deemed illegal and anyone passing them would be punished. Then on 3 April Alvarado decreed that the Comisión Reguladora’s financial position was solid enough and that the time had come to redeem the notes up to $20 (25 July 1914, 20 November 1914 and 11 January 1915). He set a month for the notes to be handed in, after which the notes would lack legal tenderDiario Oficial, Yucatán, Año XIX, Núm. 5647, 4 April 1916. The American consul in Progreso pointed out that the redemption of all this currency at the present low value of the Mexican paper peso worked out as a large profit for the Comisión ReguladoraSD papers, 812.515/91 report 17 April 1916.

On 26 May $5,000,000 in $100 notes were incinerated in the presence of Alvarado, acting manager Alonso Aznar G., vocales Miguel Cámara Chan and Faustino Escalante and various dignitariesEl Constitucional, Puebla, Tomo I, Núm. 200, 1 June 1916.

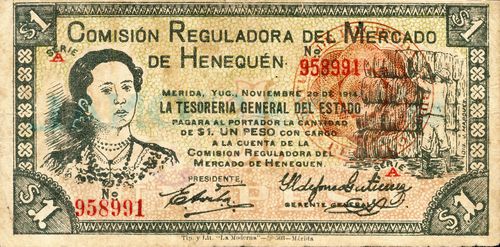

On 9 May 1916 Salvador, by decree núm. 536, authorised the Comisión to issue $20,000,000 in Bonos de Caja in national gold (oro nacional), giving as his reasons the lack of paper currency, the Comisión’s need for reserves and the fact that its gold holdings and the special taxes that it was to receive would guarantee the issueDiario Oficial, Yucatán, Año XIX, Núm. 5679, 12 May 1916. The denominations were to be:

| Number | Total value |

|

| 50c | 2,000,000 | $ 1,000,000 |

| $1 | 3,000,000 | 3,000,000 |

| $2 | 2,000,000 | 4,000,000 |

| $5 | 800,000 | 4,000,000 |

| $20 | 200,000 | 4,000,000 |

| $100 | 40,000 | 4,000,000 |

| 9,040,000 | $20,000,000 |

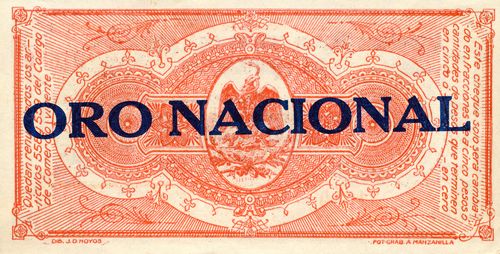

However, the need for notes was so urgent that on 13 May, in decree núm. 549, Alvarado ordered that in the meantime the 20c and 50c cheques of 27 July 1914 and the $50 and $100 notes of 24 September 1915 that, in accordance with a decree of 1 March, had been taken in by the Comisión as payment, could be revalidated as “ORO NACIONAL” and reissued. These would then be exchanged, in due course, for the new issueDiario Oficial, Yucatán, 25 May 1916.

M4156c 50c Comisión Reguladora ORO NACIONAL

M4156c 50c Comisión Reguladora ORO NACIONAL

M4157c $1 Comisión Reguladora ORO NACIONAL

M4157c $1 Comisión Reguladora ORO NACIONAL

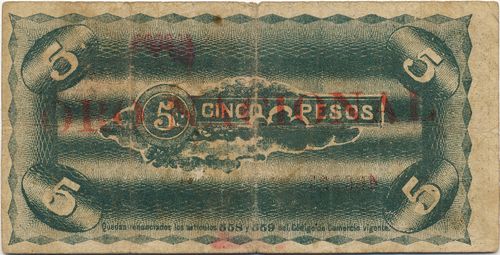

M4158c $5 Comisión Reguladora ORO NACIONAL

M4158c $5 Comisión Reguladora ORO NACIONAL

M4159d $20 Comisión Reguladora ORO NACIONAL

M4159d $20 Comisión Reguladora ORO NACIONAL

M4163 $100 Comisión Reguladora ORO NACIONAL

M4163 $100 Comisión Reguladora ORO NACIONAL

Then on 23 May, by decree núm. 550, Alvarado, blaming bankers and speculators for the economic troubles, authorised a new issue of $40,000,000 in bonos de caja of the Tesorería General in oro nacionalDiario Oficial, Yucatán, 26 May 1916. The distribution was to be:

| Series | from | to | Number | Total value |

||

| $1 | 5,000,000 | $5,000,000 | ||||

| $2 | 2,500,000 | $5,000,000 | ||||

| $5 | 3,000,000 | $15,000,000 | ||||

| $10 | 1,500,000 | $15,000,000 | ||||

| 12,000,000 | $40,000,000 |

As 'oro nacional' the notes were to have a fixed value of 50 centavos to the American dollar, and were guaranteed by half of the taxes and export duties on henequen. This money was to be collected, in gold, in the Tesorería General and held intact until the notes were redeemed.

Of these new issues only the 50c was printed locally, whilst the other values were produced in the United States by the Parsons Trading Company.

M4130a 50c Tesorería General 1710919/1701919

M4130a 50c Tesorería General 1679022/1679023

M4130a 50c Tesorería General 1679022/1679023

| series | from | to | total number |

total value |

||

| 50c | A | includes numbers 610720CNBanxico #6508 to 987616CNBanxico #6506 | ||||

| B | includes numbers 1085429CNBanxico #6507 to 1237903CNBanxico #6505 | |||||

| C | includes numbers 1679023 to 1872165CNBanxico #6503 |

Note that the numbering machine was poorly set.