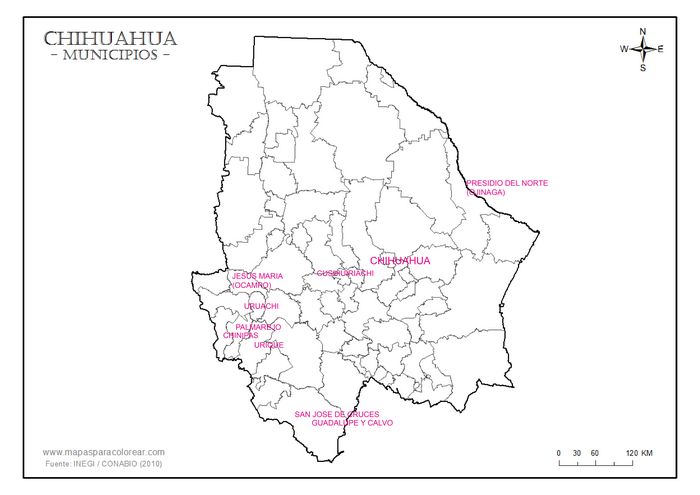

Mining scrip

Cusihuiriachic

Herrera, González, Salazar y Compañía

The business house of Herrera, González, Salazar y Compañía, founded by Manuel de Herrera, Juan María Salazar and Celso González, ran a mining business in Cusihuiriachic, and later established the first Banco Minero Chihuahuense. In 1874 thirty-six of its employees unsucessfully tried to stop the company illegally paying in wooden tokens that were only redeemable at the company store. The case went to the Supreme Court, where the judge upheld a judgement of the Chihuahua court that the company's workers had no redress against the company, nor against the state's governor or the judge for his refusal to act as the right of amparo (judicial protection) only related to government departments, not private individuals, and only to acts not to omissions. However, the court declined to fine the litigants as they were noticeably poor. It could have added that they would have been twice as poor as the company only cashed its own scrip at half its face valueEl Foro, 17 December 1874; Semanario Oficial, 30 June 1875.

The Correo del Comercio said that the workers were ill-advising in asking for an amparo rather than proceeding against the company, which it castigated for its iniquitous abuses, reminiscent of the oppression of colonial timesEl Correo del Comercio, Segunda Epoca, Núm. 1,108, 18 December 1874.

Uruachic

Compañía Minera

The Rascóns were the political bosses, leading mine-owners, and most important merchants of Uruachic from the late eighteenth century. During the thirty years preceding the Revolution, they came to control virtually every mining claim of any value in the region, as well as its largest haciendas. The family dominated local politics to such an extent that in 1908 its members held eight of ten seats on the Uruachic ayuntamiento. Family patriarchs Enrique C. and Ignacio RascónIgnacio Rascón Enriquez was born in 1836, the son of Froilan Rascón, and partner with his brothers in the El Creston, Las Animas, La Unión (union of Francisco, Ignacio and Nicolas), Santa Rosa, Santa Domingo and other mines. He died on5 February 1900 acted as state legislators and jefes politicos during much of the Porfiriato. They allied themselves with Luis Terrazas from the time when they joined him in opposition to Porfirio Díaz in the 1870s.

In November 1887 Rascón Hermanos was composed of Luz Domingo, Enrique, Epigmenio and Froilan (as comerciante).

The Rascóns emerged from the Revolution with their mining and commercial interests intact. Like the Terrazas, they had backed the Orozquistas in 1912 but evidently avoided exile because they kept a foot in both camps. When Orozquista Guillermo S. Rascón was ousted as Presidente Municipal, another Rascón was his suplente (alternate). Guillermo was eventually pardoned by Villa. During the 19 20s, the family dominated the local ayuntamiento once again and a family member was Presidente Municipal in nine of the thirteen years between 1918 and 1931.

In the 1870s the Rascóns' company, the Compañía Minera, Uruachic, issued both tokens and paper currency, the tokens being produced at the Alamos mint and the notes either produced locally or printed by the American Bank Note Company in New York. Both were redeemable at the company store, which was run by Ezequiel and Daniel Rascón. Notes in three denominations (twenty-five centavos, fifty centavos and one peso) are knownAlmada, op. cit., mentions vales with a value of two, four and eight reales. Were these the same or did he know of an earlier issue? Was he in fact referring to the tokens listed above?.

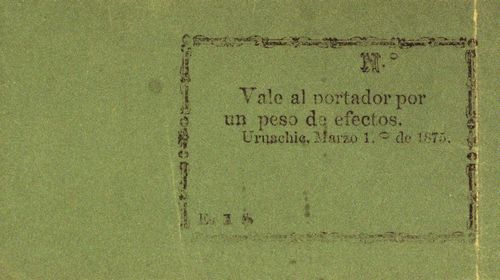

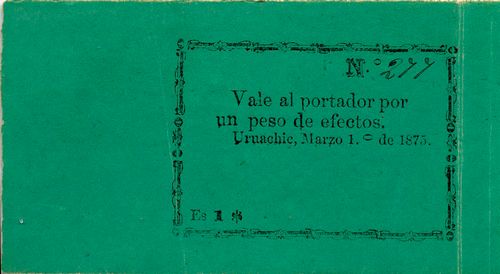

M668 $1 Uruachic

M668 $1 Uruachic

| from | to | total number |

total value |

||

| $1 | includes number 277 |

The one peso is known as a green uniface note measuring 104mm by 56mm dated 1 March 1875 with legend 'Vale al portador por / un peso de efectos'. It was presumably part of a temporary measure until more professionally produced notes were available.

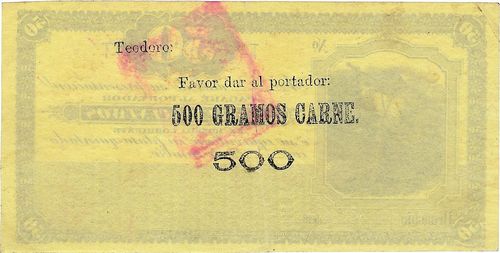

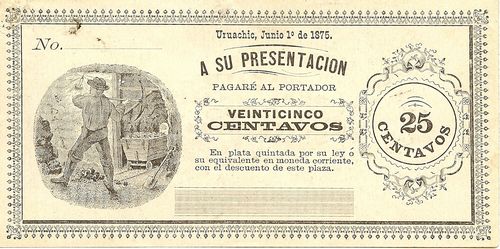

M676 25c Compañia Minera

M676 25c Compañia Minera

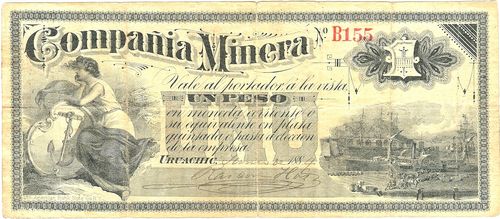

M678a $1 Compañía Minera

M678a $1 Compañía Minera

| series | date on note | from | to | total number |

total number |

||

| 25c | 1 June 1875 | ||||||

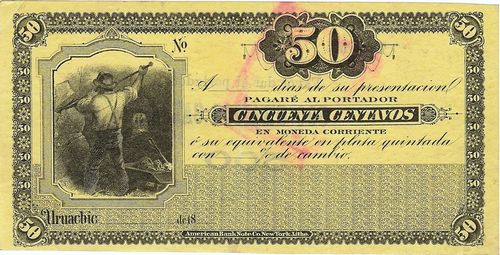

| 50c | |||||||

| $1 | B | June 1884 | includes number 155 | ||||

| E | includes number 188 | ||||||

| F | includes number 306 | ||||||

| G | includes number 439 | ||||||

| H | includes numbers 463CNBanxico #302 to 474CNBanxico #10014 |

The twenty-five centavos note (dated 1 June 1875) is payable in government-assayed silver or its equivalence in legal tender (i.e. copper coins) with the usual discount (en plata quintada por su ley ó su equivalente en moneda corriente con el descuento de esta plaza) and the fifty centavos (dated 18—) conversely in cash or its equivalence in assayed silver with a discount (a ... dias de su presentacion .. en moneda corriente ó su equivalente en plata quintada con _ % de cambio). Examples are known with the inscription ‘Teodoro: / Favor dar al portador / 500 GRAMOS CARNE/500’ (‘Teodoro, please give the bearer 500g of meat’) printed on the back. The $1 note is dated 188- and is payable on sight in cash or its equivalence in assayed or bullion silver (en moneda corriente ó su equivalente en plata quintada ó pasta á elección de la empresa). The only issued example is dated June 1884.

Urique

Casa de Becerra Hermanos

Urique in the next valley was another mining town dominated by a single family, in this case the Becerra. Juan N. Becerra moved to the region in the early years of the nineteenth century, becoming an important mineowner and local political official. His sons Buenaventura Agustín and José María expanded the family's economic holdings. Buenaventura, in particular, grew rich selling mines to foreign companies, dying a millionaire in 1907. The brothers briefly tried to obtain statewide office in 1877, when José María ran in and lost the gubernatorial election. Thereafter they allied themselves with the Terrazas. Marriage linked them to foreigners who operated their mining enterprises and to local political officials.

On 8 April 1895 Becerra Hermanos went into liquidation with its assets being bought by the Banco MineroAGN, Antiguos Bancos, Actas de Banco Minero, libro 1, 28 February 1888 to 5 January 1899.

By 1909, as well as their mining interests, the Becerra family ran the beef trade and held all federal, state and municipal posts. A newspaper reported that it represented the 'height of patronage' (el colmo de compadrazgo)El Correo de Chihuahua, 14 May 1909.

After the start of the revolution, one family member was jefe político during the revolutionary governorship of Abraham González, so that they apparently played both sides during the years of upheaval. The Becerras continued to mine and ranch in Urique through the 1930s. Relatives served in the state legislature from western districts. The family’s political rule was challenged in 1924, when angry opponents rain local boss and family member Alfredo S. Monge and his son from town.

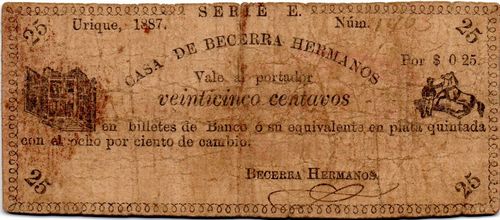

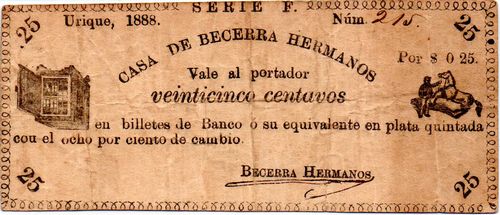

The Casa de Becerra Hermanos issued sets of notes (25c and $1 notes are known, so there was presumably also a 50c) from 1883 to at least 1889.

25 centavos

M664 25c Casa de Becerra Hermanos, Serie E

M664 25c Casa de Becerra Hermanos, Serie E

M664 25c Casa de Becerra Hermanos, Serie F

M664 25c Casa de Becerra Hermanos, Serie F

| date in note | series | to | from | total number |

total value |

|

| 1883 | A | |||||

| 1884 | B | |||||

| 1885 | C | |||||

| 1886 | D | |||||

| 1887 | E | includes numbers 1463 and 2825 | ||||

| 1888 | F | includes number 215 | ||||

| 1889 | G | includes number 10 |

50 centavos

One peso

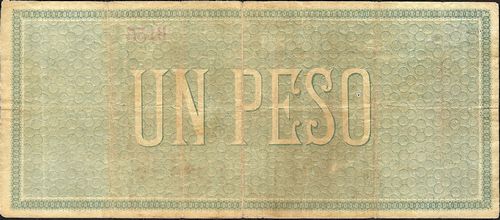

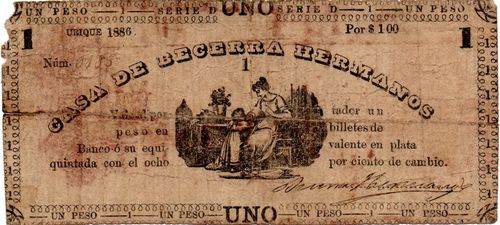

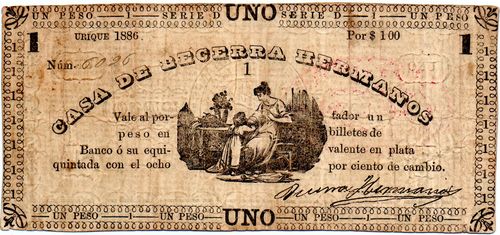

M665 $1 Casa de Becerra Hermanos, Serie D

M665 $1 Casa de Becerra Hermanos, Serie D

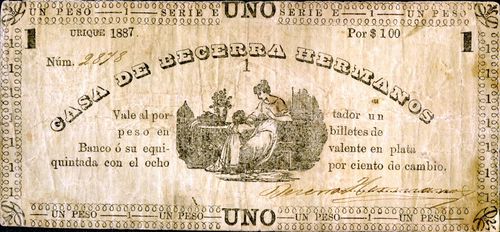

M665 $1 Casa de Becerra Hermanos, Serie E

M665 $1 Casa de Becerra Hermanos, Serie E

| date in note | series | to | from | total number |

total value |

|

| 1883 | A | |||||

| 1884 | B | |||||

| 1885 | C | |||||

| 1886 | D | includes numbers 6026 to 6135 | ||||

| 1887 | E | includes number 2878 | ||||

| 1888 | F | |||||

| 1889 | G |

These notes were payable in banknote or its equivalence in assayed silver with an 8% exchange rate (al portador en billetes de Banco ó su equivalente en plata quintada con el ocho por ciento de cambio).

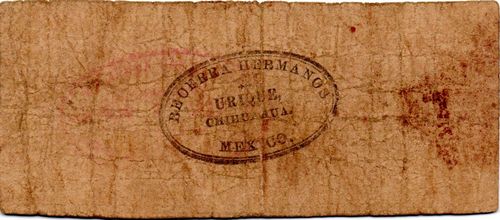

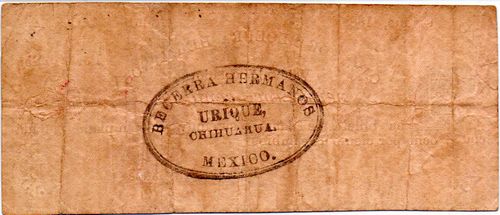

Some notes have a stamp on the reverse stating 'BECERRA HERMANOS - URIQUE - CHIHUAHUA' while another has 'BECERRA HERMS - HACIENDA DE SANTA RITA - GUAZAPARES' (Guazapares is 40 kilometres north-west of Urique).

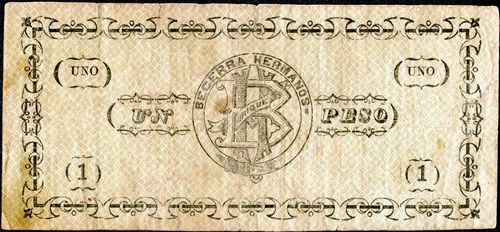

M665 $1 Casa de Becerra Hermanos, Serie D

M665 $1 Casa de Becerra Hermanos, Serie D

Hacienda de San José de Cruces

Compañía Minera y Beneficio de Plata de Freeman

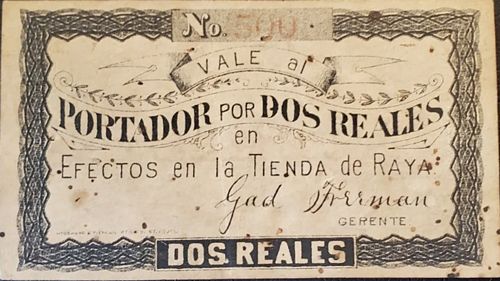

M662 2r M665 Compañía Minera de Freeman

M662 2r M665 Compañía Minera de Freeman

| from | to | total number |

total value |

||

| 2r | includes number 500 |

This mining company and smelter (beneficio de plata) issued vales al portador to be redeemed for goods in their tienda de raya. They were printed by the [ ] Printing Company of St. Louis and signed by Gad Freeman, as gerente.

|

Gad Freeman was born in Detroit, Michigan in 1836 and worked as a miner in California and Nevada. In 1888 he joined with an Arizona prospector, E. A. Bernard, to develop two silver mines, Los Juntas and the Socobon, near the town of San Jose de Cruces, in the extreme southwestern corner of the state of Chihuahua. Supplies from El Paso and machinery, including a 15-ton smelter from St. Louis, were carried on wagons from the city of Chihuahua via San Lorenzo to San Borcas, 90 miles, and from there on pack mules 185 miles, via the towns of Nonoava and Noragschi, and some small Tarumari Indian villages, and then by the only point of access across the Barranca de Huerachi, which cuts through the continental divide for more than 100 miles, with almost perpendicular walls rising from 5,000 to 7,000 feet above the bed of the enclosed torrentEl Paso Times, Ninth Year, No. 9, 11 January 1889: El Paso Times, Ninth Year, No. 30, 5 February 1889. In March 1889, Freeman joined with a group of investors to form the Canton Mina Mining Company, based in Grand Rapids, Michoacan, with a capital of $1,000,000, most of which was the San Jose de Cruces mines, valued at $975,000El Paso Times, Ninth Year, No. 74, 29 March 1889. Freeman sold a number of gold claims in August 1897El Paso Daily Herald, Vol. XVII, No. 183, 3 August 1897 and disposed of the San Jose de Cruces mines in April 1899 to some American investorsEl Paso International Daily Times, Vol. 19, No. 78, 2 April 1899. From 1900 he was in charge of the mining interests of the International Gold and Copper Company in Alamos, SonoraRock Island Argus, Vol. LI, No. 236, 23 July 1902. On 10 September 1902 Freeman was granted a concession to establish a railway line from Alamos to the port of Yabaros. He was given an extension on 4 April 1904 but failed to complete the first twenty miles within two years so the concession was voided and Freeman lost his $13,200 deposit. He died at his mine in Sonora in February 1906El Paso Daily Times, Vol. 26, 20 February 1906. |

|

Guadalupe y Calvo

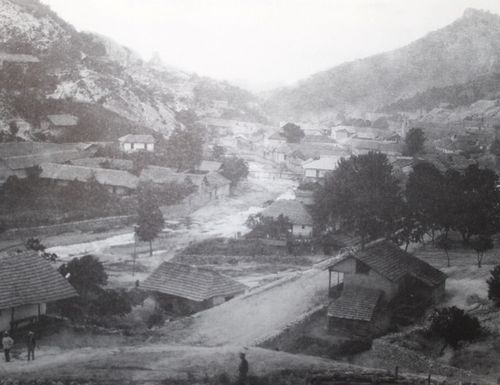

Guadalupe y Calvo in 1939

Guadalupe y Calvo is an old mining town squeezed into a narrow valley where the air is redolent of pine smoke. It is reached from Hidalgo del Parral along a road where you are constantly looking down on where you were half an hour ago or will be in ten minutes' time. The trip to the mine, however, is well worthwhile and the view from the mine entrance, the narrow gauge railway track weaving around the rock face, and the cavern that has been dug to follow the vein down below a waterfall could make you forget the appalling conditions under which the Mexicans laboured to earn their pieces of paper.

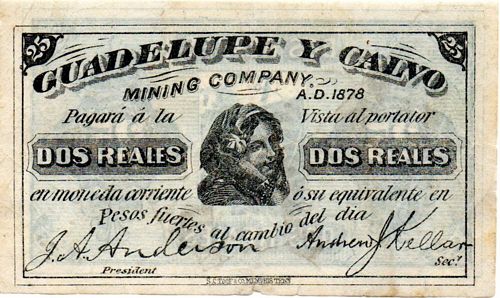

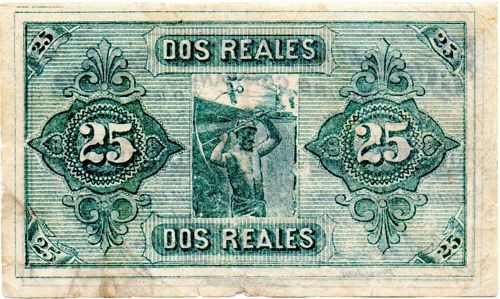

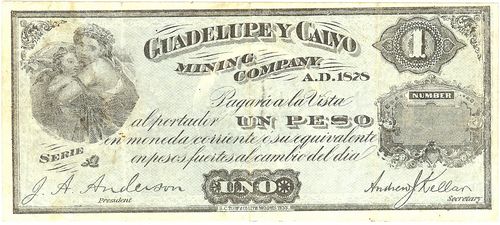

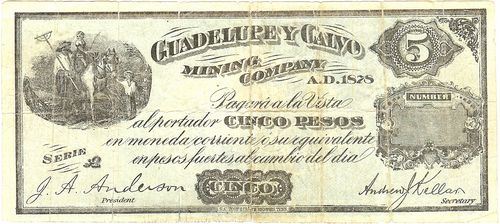

Guadelupe y Calvo Mining Company

Antonio Ochoa (state governor 1856-1861 and 1873-1877) and his brothers inherited the Nankin mine and a smelting plant here and in 1850 organised the Compañía Minera de Guadelupe y Calvo. For the next thirty years it was the most powerful mining company in this part of the state. In 1878 the mines were sold to the Guadelupe y Calvo Mining Company, based in Memphis, Tennessee, with the brothers retaining a 20% shareholding.

M635 2r Guadelupe y Calvo Mining Company

M635 2r Guadelupe y Calvo Mining Company

M636 $1 Guadelupe y Calvo Mining Company

M636 $1 Guadelupe y Calvo Mining Company

M637 $5 Guadelupe y Calvo Mining Company

M637 $5 Guadelupe y Calvo Mining Company

| series | from | to | total number |

total number |

|

| 25c | |||||

| $1 | A | ||||

| $5 | A |

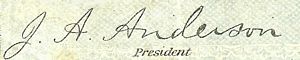

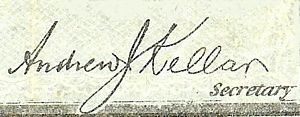

The notes issued by the Guadelupe y Calvo Mining Company are known in three denominations: two reales, one peso and five pesos. The notes are payable in copper coins or their equivalence in silver pesos at that day's exchange rate (en moneda corriente o su equivalente en pesos fuertes al cambio del dia). The two reales note is dated 1878, whilst the one peso and five pesos notes are undated. All have the printed signatures of James A. Anderson as President and Andrew Kellar as Secretary.

|

James A. Anderson was a public administrator (and judge) in Memphis by 1876, involved, inter alia, in the administration of wills and trusts. Though he appears as President on these notes dated 1878, by 1880 he had been replaced by Jacob Thompson, also from Memphis and a member of the German National BankThe Memphis Daily Appeal, 23 April 1880 and was insolvent. Indeed, Anderson was an embezzler and by 1883 had several cases against him in Chancery CourtThe Memphis Daily Appeal, 27 June 1883. One case, where, in 1876 and 1877, Anderson illegally sold three bonds worth $15,000 and misused the proceeds, even made it to the Supreme Court of the United States when the German Bank of Memphis, successor to the German National Bank of Memphis, unsuccessfully tried to recover from the U. S. government (case no. 693, German Bank of Memphis v. U S, decided 10 April 1893). |

|

|

Andrew J. Kellar was still secretary in 1880The Memphis Daily Appeal, 23 April 1880. Jacob Thompson was then president and T. H. Milburn, President of the German National Bank, treasurer.. |

|

These notes are similiar of those of the Banco de San Ignacio.

Palmarejo

Palmarejo is a small mining community in the mountainous southwest of Chihuahua on the road from Temoris to Chínipas.

Palmarejo and Mexican Gold Fields Limited

Miguel Urrea bought the mines there in 1845 and worked them for several years, and they were then sold in 1886 by his heirs, the Almadas of Alamos, to the Palmarejo Mining Company Limited. Later this company merged with the Mexican Railway Company Limited, which ran the narrow gauge railway between Palmarejo and El Zapote (the mill on the Chínipas river just south of Chínipas), to form the Palmarejo and Mexican Gold Fields Limited, which, according to AlmadaFrancisco Almada, Resumen de Historia del Estado de Chihuahua, Mexico, 1955, issued scrip though none is known.

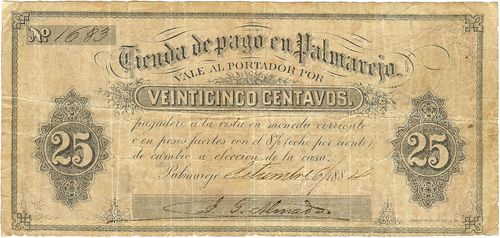

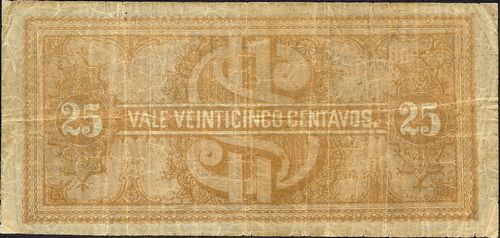

Tienda de pago

M653 25c Tienda de pago en Palmarejo

M653 25c Tienda de pago en Palmarejo

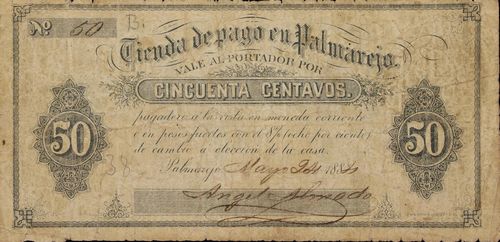

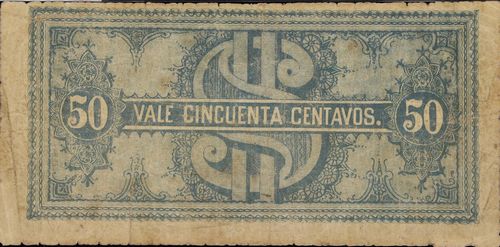

M Unlisted 50c Tienda de pago en Palmarejo

M Unlisted 50c Tienda de pago en Palmarejo

| date on note | from | to | total number |

total value |

||

| 25c | 6 October 1884 | includes number 1683 | ||||

| 50c | 24 May 1884 | includes number 50 |

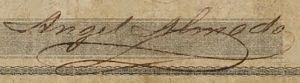

These notes are payable in copper coins or silver pesos at an 8% discount (pagadero á la vista en moneda corriente ó en pesos fuertes con el 8% (ocho por ciento) de cambio á elección de la casa). The known 25c is signed by Jesús G. Almada and the 50c by Angel Almada.

|

Jesús G. Almada was an employee of Angel Almada y Cía. |

|

| Angel Almada |  |

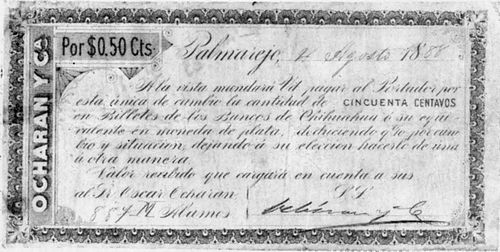

Oscar Ocháran

Oscar Ocháran, of Alamos, was a mining investor who also operated the narrow gauge railway between Palmarejo and Chínipas and issued tokens for use by either passengers or freightElwin C. Leslie, The Palmarejo Railroad Token, in Plus Ultra 69. Ocharan also operated the stage coach between Alamos and Guaymas..

His company, Ocháran y Ca, of Palmarejo, also issued cheques (única de cambio) payable in Chihuahua banknotes or their equivalence in silver coins (en Billetes de los Bancos de Chihuahua o su equivalente en moneda de plata).

M656 50c Ocháran y Ca.

M656 50c Ocháran y Ca.

| date on note | from | to | total number |

total value |

||

| 25c | 8 April 1888 | |||||

| 50c | 4 August 1888 | includes number 887 |

By 1911 Ocharan was a large garbanzo raiser in the Mayo valley, an owner of the Hacienda La Colorada and a leading producer of mescal wine and fibre in the Alamos districtThe Mexican Herald, 27 November 1911. In 1912 he went into exile in the United States.

Presidio del Norte (now Ojinaga)

Guillermo Hagelsieb

Guillermo Hagelsieb of Presidio del Norte (now Ojinaga) issued circular 10-centavos card tokens, which are known dated 1869 and 1870Richard D. Worthington, op. cit..

Guillermo (Johann Friederik Wilheim) Hagelsieb was born in Cassel, Germany on 6 March 1832 and migrated to Galveston, Texas in 1852. He eventually ended up in Ojinaga. He was Director of the official journal, El Estado de Chihuahua, in November 1885 and died in 1902.