The revolution in the Estado de México

Toluca, the capital of the state, about 63 kilometres west-southwest of Mexico City, was captured by the second Brigada of the Cuerpo de Ejército Constitucionalista ot the División del Noreste, under General Brigadier Francisco Murguía, on 8 August 1914. However, he left Toluca in November 1914 to join Carranza in his flight to Veracruz.

A notice issued by the Inspección General de Policía, dated 29 January 1915, in the names of Inspector Coronel F. Ibarra and Secretario J. M. Arriaga, declared that, amongst others, the Estado de Sonora, sábanas, dos caritas and Ejército Constitucionalista notes were of forced circulation but made no mention of revalidations. However, the Villista issues needed special attention as on 1 February the provisional governor wrote to the Presidente Municipal, recommending that he immediately use the police to ensure that all businesses that had closed establishments reopen them and, at the same time, ensure that Villista notes were accepted, since they were of forced circulation. The next day the Inspector General de Policia, Juan Camacho, reported to the Presidente Municipal that he had given the necessary ordersAMT, sección especial, caja 21, exp. 1014.

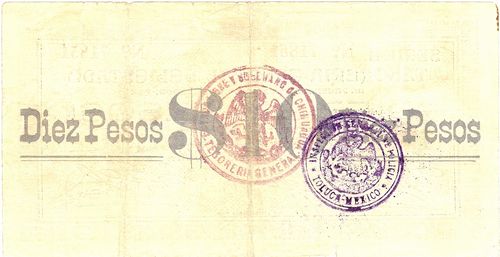

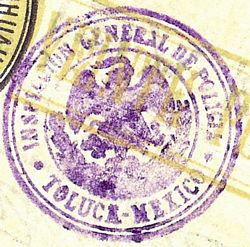

Thus, sábanas are known revalidated with a round (34mm) violet rubber stamp with: ‘INSPECCION GENERAL DE POLICIA - TOLUCA – MEXICO’ and eagle in centre.

Thus, sábanas are known revalidated with a round (34mm) violet rubber stamp with: ‘INSPECCION GENERAL DE POLICIA - TOLUCA – MEXICO’ and eagle in centre.

On 25 February 1915 Antonio García, Presidente Municipal of Calpulalpan, Estado de México, told Carranza that there was a lot of Chihuahua paper in the town and with his prohibition some people had nothing to eatABarragán, caja II, exp. 2, f. 110-111, telegram to Carranza, Veracruz, 25 February 1915.

On 6 March governor Gustavo Baz declared invalid the Gobierno Provisional de México notes issued by Carranza in Veracruz and only recognised the notes he had issued in Mexico City before the breakEl Monitor, 10 January 1915.

In March 1915 when Villista notes stopped circulating in Mexico City they appeared in great numbers in Toluca, particularly the $50 and $100 values. This ‘bad’ money drove out the ‘good’ and Governor Gustavo Baz had to authorise an emergency issue of fractional notesGaceta del Gobierno, 24 March 1915. However, the sábanas were more acceptable than Convention notes or those issued by BazGustavo G. Velazquez, Toluca de Ayer, Mexico, 1972. On 13 April the Governor decided that, until it received an answer as to which notes were of forced circulation, if anyone wanted to pay their taxes with Villista notes, offices should only accept 25% of any payment in such notes. Notices were put up to advise the public (AMT, Presidencia, caja 203, exp. 12). By April 1915 the sábanas had to be revalidated in accordance with with the Convention's decree of 23 January 1915 whilst on 30 June they were declared as being no longer of forced circulationRodolfo Alanis Boyza, Historia de la Revolución en el Estado de Mexico: zapatistas en el poder, Toluca, 1987.

On 26 August 1915 Eduardo Martínez from Sultepec wrote to the governor about the situation in San José Villa de Allende. The town had seen neither Zapatistas nor Constitutionalists, and the commercial house of Francisco Pérez Carbajal "had become a monopoly" and no revolutionary "from outside" had come to "establish order". Pérez Carbajal’s business hoarded the corn supply and accumulated all the low value paper money, and even the cartones that circulated in the town. Martínez complained that these caciques were extorting money from the populace by using the Presidente Municipal, a member of the commercial house, and the comandantes de la plaza, who disguised and tolerated the fact because they were friends of the generalAHEM, Gobernación, serie Seguridad Pública, vol. 150, exp. 29.

On 14 October 1915 the Zapatistas evacuated Toluca and it was taken over by Carrancistas, under General Alejo G. González. On the next day, González declared invalid all the notes issued by enemy factions with only the Veracruz notes as legal tenderPeriódico Oficial, Tomo XXXVIII, Núm. 31,16 October 1915.

By 1916, individuals who had incurred debts years before could not pay them off because their creditors would not accept Constitutionalist notes. In Cuautitlán creditors demanded payment in silver currency and not in banknotes, but faced with the difficulty of obtaining silver coins, debtors were unable to recover the goods, usually land, which they had given in collateral of the loan. The state government therefore ordered that debt holders be forced to accept payment with Constitutionalist notesAHEM, Ramo de la Revolución Mexicana, vol. 87, exp. 19.

By mid-1917, the problems of shortages, combined with the circulation of Constitutionalist notes, became more acute, as traders refused to receive them, demanding to be paid in gold or silver coins. The $1, $2, $5 and $10 notes of the Veracruz issue were the most rejected. Similarly, landlords also did not accept the Veracruz notes in payment of rent and even the municipal public employees themselves refused to receive payment of their salaries with themAHEM, Ramo de la Revolución Mexicana, vol. 85, exp. 9; vol. 87, exp. 18, 20, 21 and 44.

During October and November 1917, the question of the circulation of Constitutionalist notes continued to be one of the major problems confronting the government of Pascual Morales y Molina. Establishments that sold bread were among the most affected, as their merchandise was paid for almost entirely with Veracruz paper but this, in turn, was scarcely accepted by their supplier or their workers, forcing them near to closure. To resolve this situation, the state government had to increase the circulation of infalsificable notes by the amount of $200,000 so that bakers could easily redeem Veracruz' notes for infalsificablesAHEM, Ramo de la Revolución Mexicana, vol. 85, exp. 10.

.