The Credit Foncier Company

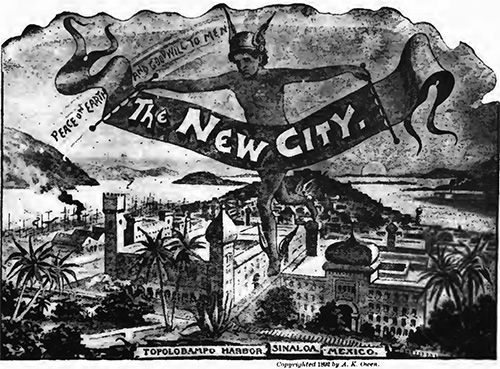

The driving force behind this company was Albert Kimsey Owen (1847-1916). At the age of twenty-four Owen began working as a surveyor and civil engineer for William J. Palmer and the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad, and in the spring of 1872 he was sent to survey the west coast of Mexico for promising harbour sites, and there he had his first look at Topolobampo Bay, near Los Mochis, Sinaloa. Thereafter Owen was committed to the dream of establishing a port at Topolobampo.

Owen’s original plan was to build a railroad from Texas to Topolobampo (the Texas, Topolobampo, and Pacific Railroad) but he also envisaged settlements at the Mexican end including a grand city called Pacific City as well as several agricultural colonies along the Fuerte River. Having grown up with a Quaker father and having lived for a time at Robert Owen’s utopian colony in New Harmony, Indiana, he was a staunch and idealistic socialist. So his plans envisaged a cooperative colony where the reorganization of labour and distribution followed the principles laid out in his essay Integral Co-Operation.

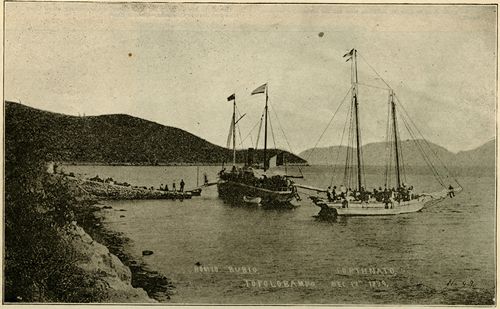

The Straits of Joshua looking east. The old stone pier with the “Romero Rubio” unloading the Hoffman party, December 1890. The point of land, at the eastward, is known as “the toe”. The heel of the foot stretches into Ohuira to the north. The mountains in the distance are on the peninsula of San Ignacio. These will be reserved for park and pleasure resorts forever.

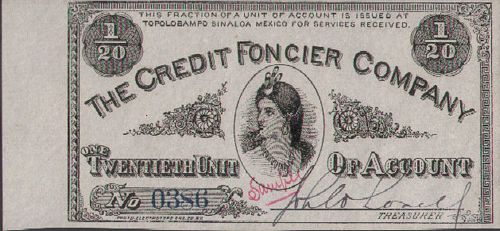

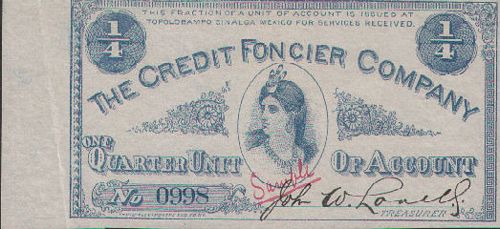

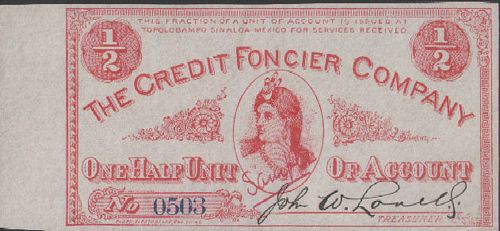

This socioeconomic treatise determined that labour was the source of all wealth, and that wealth, the end product of labour, should be justly dispersed through a system of credits. Hence the Credit Foncier Company of Sinaloa, which issued stock, script and credits in return for labour.

The working-day had at first a value of two dollars. These lithographed certificates of work could be exchanged in the colony for every necessary commodity, and Owen hoped that in case the colony he had created ever attained to prosperity and played a part in the world, these notes would be taken everywhere as a medium of exchange.

Hertzka declared the replacement of coin by "credit notes" - proposed also by Bellamy - to be just as unnecessary as it was impracticable. In a public letter to the body of directors of Topolobampo, in May 1892, Theodore Hertzka wrote:

.... Unnecessary, because money in itself is just as harmless as any other instrument, for money is nothing but an instrument designed to perform certain services in the exchange and preservation of wealth. It has, of course, become a tool of oppression and plunder-but what acquisition of the human intellect has not become that in the same degree? .... Impossible, because the human industrial organization cannot even be imagined without a measure of value; and money, though not indeed an absolutely perfect one, is yet the most perfect of all measures of value actually existing. Human labor power would indeed be the worst imaginable of all measures of value, for a measure, to be universally useful, must itself be something fixed, capable of being laid hold of, as unchangeable as possible, whereas human labor power changes its value incessantly.

Owen, however, believed that money could be almost entirely set aside. Thus interest on capital would disappear of its own accord, and with it also its mischievous drawbacks. From the fact that the carrying-on of the public works (means of transportation and communication, lighting, theaters, etc.) would bring into the community rich profits which would suffice to cover public expenditure, the raising of taxes would be superfluous. Again, from the fact that the people would possess their own houses, that there would be no private shops, and that the land and all aids to production were to be used for farming free of charge, rents and leases would disappear. And doing away with interest would make an "unearned increment," which with justice is so much dreaded in the present economic world, an impossibility. Only work could secure the means of livelihood in Topolobampo. "With us," wrote Owen in one of his numerous pamphlets (May, 1891), "everyone who is capable of work must lie under the obligation of productive labor. We will do away with drones, according to the model of the bees; gamblers, idlers, speculators, jobbers, middlemen, etc., have amongst us just as little to do as women of doubtful occupation."

M744 1/20 unit Credit Foncier

M744 1/20 unit Credit Foncier

M745 1/10 unit Credit Foncier

M745 1/10 unit Credit Foncier

M746 1/4 unit Credit Foncier

M746 1/4 unit Credit Foncier

M747 1/2 unit Credit Foncier

M747 1/2 unit Credit Foncier

| from | to | total number |

total value |

||

| 1/20 unit | includes number 0386 (sample) | ||||

| 1/10 unit | 0001 | includes number 0007 (sample) | |||

| 1/4 unit | includes number 0998 (sample) | ||||

| 1/2 unit | includes number 0503 (sample) |

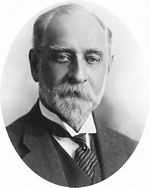

The samples are signed by John W. Lovell.

John Wurtele Lovell was born on 6 November 1851 in Montreal, Canada where his father, John Lovell, was the founder of the Lovell Printing and Publishing Company. John was apprenticed to his father at a young age and in 1873 was sent to manage his father’s printing plant in Rouses Point, New York. Three years later, he formed the publishing firm of Lovell, Adam & Company along with his father and fellow Canadian G. Mercer Adam. The firm was soon renamed Lovell, Adam, Wesson & Company with the admittance of Francis L. Wesson in New York City. In 1878 John W. Lovell became an independent publisher but failed in 1881. He established the John W. Lovell Company the next year, also located in New York City. Lovell took advantage of the lack of international copyright laws and was well known as a pirate and publisher of non-copyrighted books. Lovell reprinted cheap reprints for the masses both in series of paperbound and cloth volumes. Lovell's Library, a series of paperbacks priced at ten, twenty, or thirty cents was probably his single greatest achievement in terms of popularity. In 1888 John and his brother Frank formed the Frank F. Lovell & Company in New York. In June 1889 John announced his intention to form a “Book Trust” in order to eliminate competition and intense price-cutting among the cheap book publishers. In essence, Lovell was proposing a monopoly to control production costs in the absence of international copyright laws. Publishers were offered the opportunity to join the monopoly or be forced out of business. Although many publishers were dubious of Lovell’s grandiose plans, he did manage to organize the United States Book Company in July 1890, which initially numbered about a dozen firms, including the Frank F. Lovell & Company. Within three years, however, this firm went into bankruptcy and by 1900 Lovell had completely disappeared from the annals of publishing. Lovell was an ardent reformer and loyal supporter of Albert Kinsey Owen. He played an important role in American theosophy, being a founding member of the Theosophical Society. He died in 1932. The New York Times published an obituary on 22 April 1932. |

|

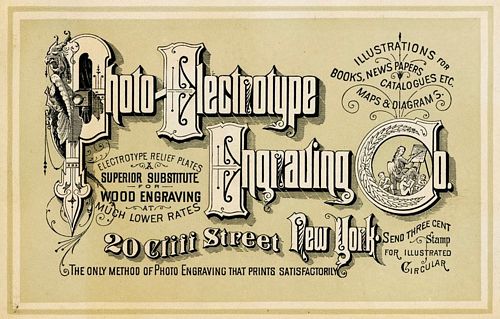

All the notes were printed by the Photo Electrotype Engraving Company of 20 Cliff Street, New York.

Supplies for the colonists were purchased through the commissary, and exchanged to colonists for credits (script) or money, whilst the produce of colonists were received by the commissary, credits being given to the producers. The colony was started in 1886 but ultimately failed, for a variety of reasons. There were practical difficulties. Products delivered by colonists to the commissary were not always saleable, yet the producers demanded credits that they could exchange for other goods. “Instead of giving credits on the basis of a service for a service, we have given them upon the communistic principle of ‘to each according to his needs’ ... we have got to conduct the Colony on business lines; we cannot afford to make it a charitable asylum where there is free food without labor.”

How to balance the needs of colonists against their earnings became a subject of much controversy. Single men earned as much as the heads of families - yet families have to be fed in a cooperative commonwealth. This issue was resolved by allotting a five-day ration per week to non-productive members of families, but single men maintained that as they worked all day in the fields in exchange for credits, the same as the family men, and helped provide food for the families, they were entitled to have their clothes washed and mended, and their bachelor quarters cared for. At this point many of the women balked, although some women worked long and patiently in the cause of complete Integral Cooperation.

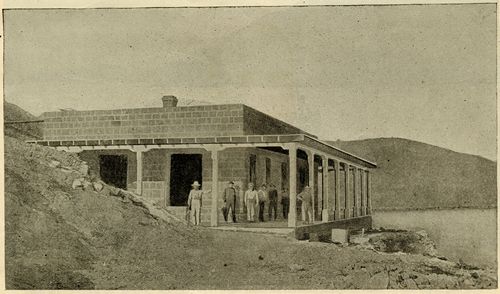

The Custom House is 50 x 40 feet, with a 10 ft. wide porch on three sides. It is built of red porphyry and is on the south-east corner of the block, 600 x 300 ft., which is reserved for Federal offices. Pioneer Cove is plainly seen to the east. The cost was $8,109 Mexican silver, and was entirely the work of the colonists, who even burnt the lime and made 80,000 bricks to cover the roof and to make the fireplaces and chimneys. Friend Hawley stands at the corner of the house. The others are too indistinct to be recognised.

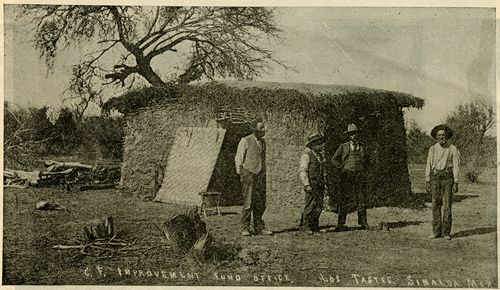

The Headquarters of The Kansas Sinaloa Investment Company at Los Tastes. It is a wattle, or a house with woven brush sides plastered with mud and having a flat brush roof covered with earth. The tree is a mesquite, a species of locust or acacia. The mesquite is the largest wood we have on our lands. Director Wilber stands in front of the door; next to him is Hon. C. B. Hoffman, President of The Kansas Sinaloa Investment Company, and on the extreme right is friend E. E. Thornton, who is now (July, 1892) in Puget Sound, Washington, getting lumber for the Colonists.

Owen left the colony in 1893 and by then it was, for all intents and purposes, defunct. Owen’s proposed railroad, which eventually became the Chihuahua and Pacific Railroad, was not fully realized until 1962.