The crisis of 1935

Twice in the twentieth century, in 1935 and again in 1943, Mexico had to resort to the issue of bearer cheques (cheques al portador) to overcome a temporary shortage of small change, caused by the disappearance of silver coins.

This method had been used during the Mexican Revolution, and occasionally since in a few locations, but in these two instances the phenomenon was nationwide. Although some cheques were issued by private businesses for their own employees, the usual procedure was for the local Chamber of Commerce (Cámara Nacional de Comercio) to contract with the local banking institutions. The Chamber would deposit a sum of money to guarantee the cheques and recoup its money when it sold the cheques in bulk to businesses that needed them: the bank would use the deposit to redeem the cheques when they were handed in (originally in multiples of five pesos since that was the smallest banknote, but when the new Banco de México $1 notes arrived, they could redeem smaller amounts).

This procedure could be considered to breach the Federal Government’s monopoly on issuing paper currency and there were occasional complaints but the Secretaría de Hacienda acknowledged the dire circumstances. Thus on 5 May 1935 the Secretaría declared the issue of $1 cheques de caja legal. On 16 May 1935 Secretario de Hacienda Narciso Bassols suggested that the Dirección de Correos y Telégrafos tell all their offices to accept the $1 and $2 cheques al portador that had been issued by local Cámaras de Comercio.

The cheques were of voluntary acceptance, and occasionally public officers refused to accept them, but generally, as they were redeemable on demand, they were readily accepted and helped greatly to relieve the crisis.

Occasionally, existing cheques were overprinted “AL PORTADOR” and with a discrete denomination, but more usually, because of the volume needed, the cheques were specially printed.

The 1935 crisis began when the United States passed its American Silver Purchase Act on 19 June 1934: this caused to price of silver to increase and as a result, in Mexico, silver coins began to be hoarded to be remelted at a profit. On 25 April 1935 the Mexican government reacted with a series of reforms, changing the fineness of its coinage, and withdrawing silver coins from circulation. It had ordered 50c coins (tostones) and $1 Banco de México notes from the United States but until these arrived the sudden shortage of small change led to these “necessity notes”. When the crisis passed most of these cheques were redeemed (out of $10,000 issued by the Uníon Nacional de Industria y Comercio in Guadalajara only $18 was not handed in) and so survivors are extremely rare.

Monterrey

No notes are currently known from Monterrey so much of the following is conjecture, to be tested if and when examples appear.

La Cámara Nacional de Comercio

In Monterrey, on 6 May the Cámara Nacional de Comercio held a meeting of local businessmen. Although the problem was less severe than in other cities, they agreed that the five local banks should issue $1 cheques drawn on the Banco de México[images needed]El Porvenir, Núm. 6874, 7 May 1935. The banks will have been the recently formed Crédito Industrial de MonterreyThe Crédito Industrial de Monterrey, S. A. was organized and began operations in February 1932. The reason for its establishment was to furnish an efficient and economical service for manufacturers and merchants who had been under credit strain, as other local banks in Monterrey had undergone a serious setback after the passing of the monetary law in June 1931. The bank’s capital was totally subscribed by local manufacturers and merchants, and therefore it was named Crédito Industrial de Monterrey. The company did a general banking business but specialized in the discount of commercial paper and collateral loans secured by raw material. One of its principal stockholders besides those mentioned was the Banco de México. All the original officers of the bank had been trained in the United States, and its manager, Roberto Riveroll, was until 1931 agent of the Banco Nacional de México in New York., the Banco de Nuevo León, the Banco Mercantil de Monterrey, the Banco Comercial de Monterrey and probably the local branch of the Banco Nacional de México. The issue would at first be limited to $2,000 for each bank or $10,000 in total. The first issue was taken up in less than two hours, and by 12 May $17,000 had been issuedEl Porvenir, Núm. 6879, 12 May 1935.

| from | to | total number |

total value |

||

| $1 | issued by the Crédito Industrial de Monterrey |

||||

| issued by the Banco de Nuevo León | |||||

| issued by the Banco Mercantil de Monterrey | |||||

| issued by the Banco Comercial de Monterrey |

|||||

| issued by the Banco Nacional de México |

|||||

| $17,000 |

Bernardo Elosúa was Presidente of the Cámara at this time, so was probably one of the signatories.

|

He returned to Mexico and after working for a railroad company, in 1929 acquired the largest brick company in Monterrey, which had been practically abandoned by its American owners because of the stock market crash. La Ladrillera Monterrey S.A. resumed work and over the next few decades would become the largest and most productive brickmaker in the country. In 1937, Bernardo Elosúa went on to found Impermeabilizantes y Pinturas S. de R.L. (in 1943 renamed Pinturas Berel from the first letters of his name). As he belonged to a family hit hard by the Revolution and witness to numerous tragedies perpetuated during the following years, Bernardo, his friends and family, sought alternatives, and so in 1939, he headed the delegation of New León businessmen to the founding conference of the Partido Acción Nacional, formed part of the party's first National Council and later served as President of the party’s council in his home state. In 1973, Bernardo Elosúa Farías handed over direction of his companies in 1973 and died in Monterrey om 31 January 1979. |

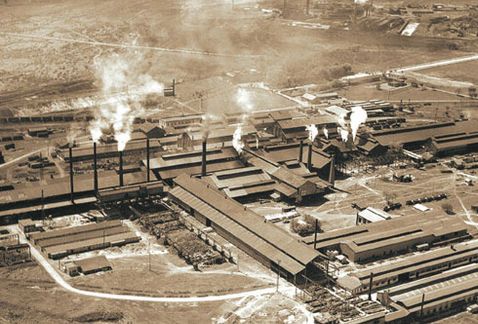

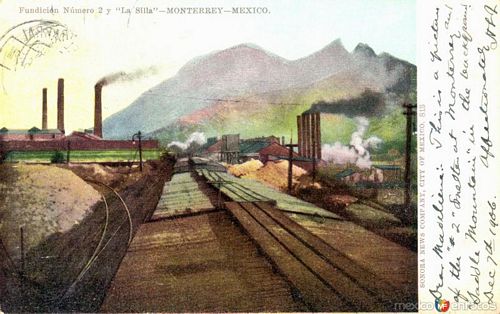

La Compañía Fundidora de Fierro y Acero

the Compañía Fundidora de Fierro y Acero de Monterrey issued $1 notes[image needed].

| from | to | total number |

total value |

||

| $1 |

On 27 May the company announced that their $1 cheques had been counterfeited and so were being withdrawn. Holders were given until 31 May to present them for payment at the Crédito Industrial de MonterreyEl Porvenir, Núm. 6895, 28 May 1935: El Siglo de Torreón, 31 May 1935. Coronel Cejudo, of the secret service, set his staff on the trail of the counterfeiters. Agent Vicente Montemayor discovered that the Imprenta y Litografía “El Modelo” had sold 60 sheets of security paper to Fidencio Novoa Ramírez, who had a printing press at calle del 5 de Febrero no. 52 (Colonia de la Independencia). There the agents found blanks ready for printing, and Novoa Ramírez confessed that two individuals had asked him to print counterfeit Fundición chequesEl Porvenir, Núm. 6896, 29 May 1935.

Bernardo Elosúa Farias was the posthumous son of Bernardo Elosúa y González, one of the founders of the

Bernardo Elosúa Farias was the posthumous son of Bernardo Elosúa y González, one of the founders of the