Villa's sábanas

The early rebels financed themselves by loans (forced or otherwise), confiscations and downright theft. Thus, on 9 April 1913, 250 men under Villa's command held up a train en route from Ciudad Juárez. Villa and twenty-five of his men boarded the train, looting 121 bars of silver bullion with a value of about $160,000“On date of 9th inst, train No. 7 of the M.N.W. en-route from Juarez, was held up by two hundred fifty men under command of “General” Pancho Villa and “Major” Juan Dozal.

The train was stopped at kilometre 71, near Chavarria, and backed up to San Andres, where the express car was looted of 121 bars of bullion consigned as follows:

W/B/30/4/8/13, Creel to Chihuahua, covered by two bars silver bullion, $2000.00, shipped by Y. Ramírez to Banco Minero; four bars silver bullion $4000.00 shipped by J. Celada to La Paz; one bar silver bullion $1000.00 shipped by R. Martínez to Banco Sonora

W/B/48/4/8/13, San Juanito to Chihuahua, covered forty two bars mixed bullion, $65,520.00, shipped by Yoquivo Dev. Co. to Banco Sonora.

W/B/48/4/8/13, Creel to Chihuahua, covered eleven bars silver bullion, $11,000.00, shipped by Santo Domingo Mining Co. to J.W. Dove, Agent Wells Fargo & Co.

W/B/48/4/8/13, covered one bar silver bullion, $1000.00 shipped by J. Bustamante to El Nuevo Mundo, San Juanito to Chihuahua.

W/B/30/4/8/13, Creel to Chihuahua covered fifty nine bars silver bullion, $70,257.83 shipped by Batopilas M. Co. to Banco Minero. One bar was recovered, having been overlooked by Villa and his men, after having been counted and receipted for.

W/B/48/4/8/13, San Juanito to Chihuahua, covered three bars mixed, $4500.00, shipped by A. Seyffert & Co. to Banco Sonora. One small bar which messenger had in portable safe, was saved.

Total number of bars taken was one hundred twenty one, but receipt was issued by Villa for one hundred twenty two. The portable safe was not broken open, and Messenger Artalejo removed all valuables from his local safe and placed in his suit case; when Villa ordered him to open the local safe, he did so, at the same time informing him that he had no valuables in this safe. No freight was molested.

I am informed that after the bullion was taken, that the men did not leave in a body, but scattered in every direction, the bars having been distributed among the lot. General Babago has been notified, but no move has been made to pursue them.

I had never been informed of the movement of this bullion; I did not know that it was on the train until advised by the bank. Agents had no authority to accept any except that of the Yoquivo Co. who, when they moved their offices to the mines, filed release in this office, and asked for the order for Agent, to accept their shipments, which I gave them. However, I informed them that whenever conditions were bad in this district, I would advise them to hold, but as I received no advice of the movement, I of course, could give them no advice. At request of Bank, I advised Chas Qualey, the manager, who is in Kingman, Arizona, of the loss.

At the time of the robbery, an Acta was secured by Messenger Artalejo, and names of twenty witnesses thereto. This Acta and receipt of Villa for the 122 bars is herewith attached. I have taken an impression copy of both, and am guarding here in the office in case anything should happen to the original.

It is the general opinion, as well as my own, that Villa had received advance information as to the movements of these shipments. There was also another occurrence that strengthens this belief. One of Villa’s men went into the coach and took a drink out of the water tank; he immediately exclaimed, “I am poisoned”; Villa spoke up and said, “What is the matter with that water”? and tipped the tank over, and took out gold bars which a passenger had hid in the tank.

Will advise you of any further developments in the case, but I am of the opinion that none of the bullion will be recovered, unless it is through the assay offices here.” (letter from Route Agent, Compañía Mexicana de Express SA (a Wells Fargo subsidiary) to J.J. Egan, Torreon, 11 April 1913, Bancroft Library). As the silver bars were registered, it would have been nearly impossible to sell them quickly on the open market so Villa ransomed them for $50,000 cash. On 3 May he met with two representatives from Wells Fargo and the mining companies that owned the silver and agreed a price“As per my telegram of this morning, Qualey and I left here for conference with Villa; we encountered him at San Andres, so we got off there and had our talk. Villa would not come down one centavo in his demands, and Qualey finally agreed to them. The bullion is to be delivered to us Monday at Bustillos, I to remain with them until Qualey arrives with the money on Tuesday. The terms are as follows:

$20,000.00 is to be paid at once; $20,000.00 in thirty days and the balance at the end of the next thirty days. Of course, should the Constitutionalistas win before the other payments are made, it will not be necessary to make them, and from the present indications, it looks to me as if they will do so in a very short time. In addition to this, Villa promises that he will not molest any more shipments of bullion belonging to any of the parties who are concerned in the present loss with the exception of Ygnacio Ramirez. He states that he will not give him any protection at all.

For reasons which you will readily understand, Mr. Qualey wishes you to keep the terms &c strictly confidential. Of course, I know that it will be necessary for you to inform the higher officials, but do not let any member of the Junta or any one else know of the terms. Regarding the Junta; their letters did not amount to anything; Villa simply glanced over them and reiterated his statement that there would be no change in his terms”.(letter from Route Agent to J.J. Egan, 3 May 1913, Bancroft Library). Villa got his cash, but the mining companies never got all their silver back as Villa returned only 93 bars, claiming that the rest were stolen by his men. Wells Fargo clearly did not want anybody on either side of the revolution to know it had played a role in the settlement and they and the mining companies did not want to find themselves accused of backing the losing side so they kept the matter secret“Thank you for copy of your letter to Mr. O'Brien, advising relative to the return of bullion shipment, by the rebel commander Villa. It is my understanding, however the bullion has been returned and the $50,000.00 paid by the mining company, and that we took no part in it.

You of course understand the reason that we could take no part in the payment of this money, is because should we have enemies in the government, they might interpret our action as aiding and abetting the enemies of the government, and that we were only taking this means as a subterfuge to pay to the rebel forces money for their maintenance. For that reason, you of course will see the necessity of our keeping entirely free from anything which could be construed against us.” (letter from E.R.Jones, Executive Vice-President, Wells Fargo And Company Express SA, Los Angeles to J.J. Egan, El Paso, 10 May 1913, Bancroft Library).

Villa had received some funds from Carranza and asked him once more for money following the capture of Ciudad Juárez on 15 November 1913, but Carranza did not even answer Villa’s telegram.

In Chihuahua there was a dire shortage of money. People were hoarding silver, as people always do in times of crisis. Much of the paper money had been taken away by the retreating members of the oligarchy, and many of the notes that had been accepted until then as legal tender, such as those of the Banco Minero, were now being rejected by merchants and businessmen because it was not clear whether the new government would honour the old notes.

The first of Villa’s troops entered Ciudad Chihuahua on 1 December 1913. Villa entered on 8 December and two days later, on 10 December, as Provisional Governor, decreed[text needed] that the Tesorería General del Estado issue paper money to support his division and revive the economy of the state. Carranza immediately sent two emissaries, Luis Cabrerra and Elisio Arredondo, to Chihuahua to convince Villa to rescind his decree. Villa received them with great courtesy and listened attentively to their case that Carranza should handle all financial and economic matters of the revolutionary government. When the two men had finished, Villa told them to tell Carranza that he would print his own money and not beg for any more handoutsAIF, Revolución constitucionalista, 1, 201, Venustiano Carranza to Silvestre Terrazas, 18 December 1913. However, Villa did ask Carranza on 17 January 1914 for $5m to establish the Banco del Estado, and during January, April and May Carranza’s Tesorería General sent three consignments totalling $3,963,906 (Francisco R. Almada, La Revolución en el Estado de Chihuahua, México, 1965).. Carranza later claimed that he gave Villa permission to issue ten million pesos to pay for the costs of the war within the state of Chihuahua.

The notes were put into circulation on 12 December with the government warning that in future only they and those issued by Carranza would be guaranteed by the Constitutionalist government, whilst other private issues (including presumably banknotes) were subject to risk until such time as it was possible to force the issuers to redeem themPeriódico Oficial, 15 December 1913.

John Reed describes it as all done in a cavalier manner.

Villa himself said: ‘Why, if all they need is money, let’s print some’. So they inked up the printing press in the basement of the Governor’s palace and ran off two million pesos on strong paper, stamped with the signatures of government officials, and with Villa's name printed across the middle in large letters. The counterfeit money, which afterwards flooded El Paso, was distinguished from the original by the fact that the names of the officials were signed instead of stamped.

This first issue of currency was guaranteed by absolutely nothing but the name of Francisco Villa. It was issued chiefly to revive the petty internal commerce of the State so that the poor people could get food. Yet almost immediately it was bought by the banks of El Paso at 18 to 19 cents on the dollar because Villa guaranteed it.

A decree ordered the acceptance of his money at par throughout the State. Another decree ordered sixty days’ imprisonment for anybody who discriminated against his currency.

Still the silver and bank bills refused to come out of hiding, and these Villa needed to buy arms and supplies for his army. So he simply proclaimed to the people that after February 10 Mexican silver and bank bills would be regarded as counterfeit, and that before that time they could be exchanged for his own money at par in the State Treasury. But the large sums of the rich still eluded him [until he called their bluff]John Reed, Insurgent Mexico, New York, 1914.

The effect of issuing these notes, known as sábanas (bedsheets) from their size and plain backs, was that merchants closed their stores or asked different prices for their goods depending on the currency offered, and the notes were immediately blamed for an increase in prices. As Reed states, Villa needed to legislate to enforce their acceptance. According to an American newspaper, in Ciudad Juárez, the sábanas’ value was established “upon a Mauser and Winchester basis. In the first two weeks of its appearance in the border city it was looked upon with doubt and at first was refused by the merchants and even refused in the gambling halls. Probably the first case on record which established a market for Villa money is the fact that one of Villa’s officers tendered a fifty dollar bill for use at the roulette table. It was promptly refused and a bullet was accepted by the dealer instead. There were at that time several other cases where the value of Villa’s money was established over the sight of a rifle barrel. As a result it rapidly came into general use and public favor in Juárez and ChihuahuaAlbuquerque Journal, 4 April 1914”.

As the banks in Chihuahua had refused to reopen, on 10 January 1914 Governor Chao gave people thirty days to exchange their banknotes for sábanas and other Constitutionalist currencyPeriódico Oficial, 11 January 1914. Even when this period expired, State Treasurer Vargas continued to allow the poorer people to exchange their notesPeriódico Oficial, 22 February 1914.

On 4 February Carranza told A[drián] Aguirre in Ciudad Juárez that he could not send the quantity of notes that the latter wanted and that while they were waiting for the new issue the government in Chihuahua could continue issuing notes to cover the costs of the army. These would then be exchanged for the new issueCEHM, Fondo MVIII, telegram Carranza, Culiacán to A. Aguirre, Cuidad Juárez, 4 February 1914. On 28 February Carranza (decree núm. 21) at Nogales made the paper money of six states (including Chihuahua) that had his approval to issue notes forced currency throughout the territory controlled by the Constitutionalists.

On 11 April Villa wrote to Carranza from Torreón that, as his troops had grown to 15,000 men, he had ordered the state government in Chihuahua to continue issuing paper money to cover their costs. He hoped that these would later been redeemed with Carranza’s Constitutionalist paper and asked when Carranza would begin making the remittances that he had offeredCEHM, Fondo MVIII, telegram Villa, Torreón, to Carranza, Cuidad Juárez, 11 April 1914.

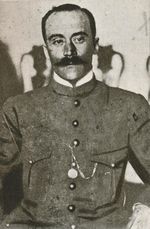

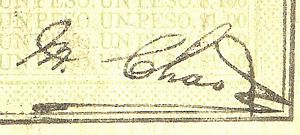

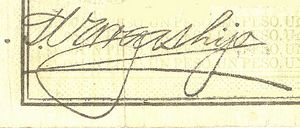

Signatories on the sábanas

The sábanas carry Villa’s name as Provisional Governor, and the signatures of Manuel Chao, as Interventor, and Sebastián Vargas hijo, as Tesorero del Estado.