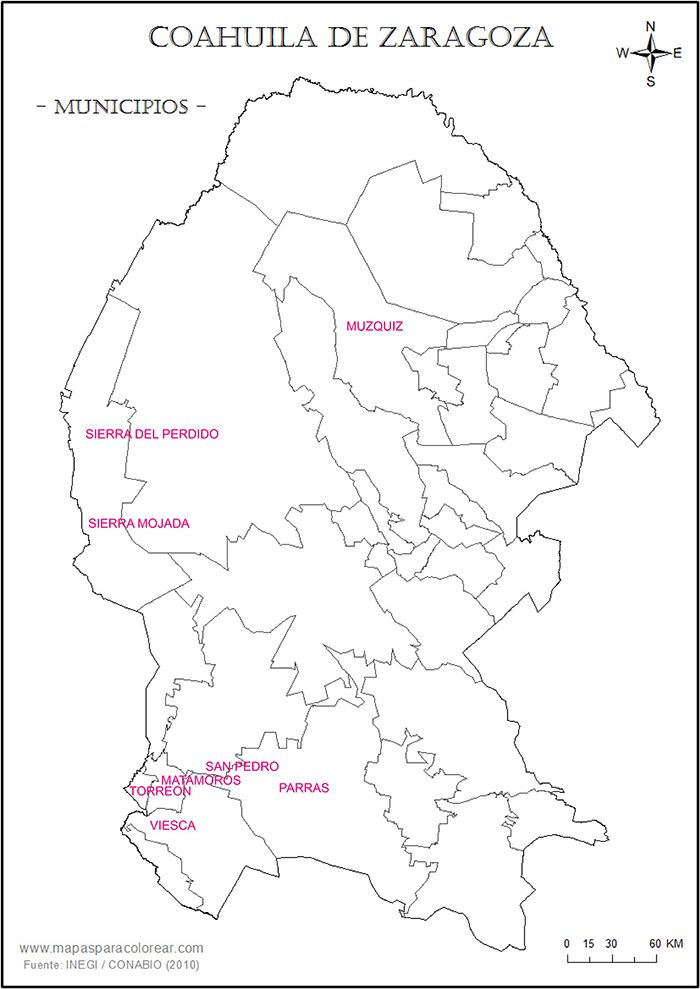

Private issues (San Pedro and Parras de la Fuente)

As stated before, on 12 November 1913 the Mexican Herald reported that on the cotton plantations in the Laguna district picking was going on though, as the planters would not be able to market their cotton, they would be obliged to store it until the railroads re-opened. The greatest difficulty that the merchants and planters had to contend with was the scarcity of money. The rebels had not issued any fiat money, as they had done in Durango, but a number of the large planters were paying their employees in vales, which were accepted by the merchants of Torreón and surrounding towns. When a merchant had accumulated a number of these vales, amounting to about $100, he turned them over to the planter who had issued them and received a draft for the amount. The plan, so far, was working well with the vales passing as currency and not being discountedThe Mexican Herald, 19th year, no. 6647, 12 November 1913.

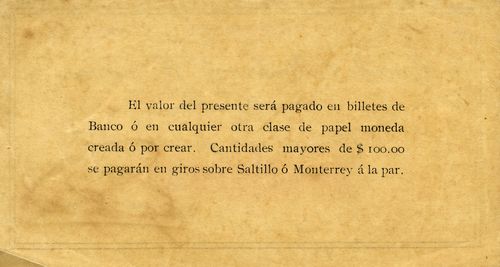

An article in the Mexico City newspaper El Imparcial in April 1914 explained how the revolutionaries had enforced their loans from businesses. In this colourful account, group of bandits would show up, and armed to the teeth, demand from the owner a large sum for "expenses of the revolution". The owner would show that he had nothing in his strongbox, because due to the lack of communications, cash and notes were scarce. Then the bandits would demand from the company an issue of notes of various values, until the required amount was completed. In this way the rebels managed to gather several million pesos, which were put into circulation, also by force. All the paper issued passed to third parties, who paid the vales in money or merchandise, to be redeemed when the issuing houses had cash to pay for them. If these companies did not recognize their notes, because the money was taken from them by force, those who would lose would be the holders of the notes, not the rebel leaders who had already collected their value in silver. The article mentions that companies that had issued vales to be paid as soon as communications were restored included La Industrial, la Compañía de Tranvías de Torreón, the casa of Guillermo Purcell, the casa of Ritter, the casa of Trad and various others in Gómez Palacio, San Pedro de las Colonias and Torreón. The newspaper had seen examples of 5c, 10c, 20c and 50c but had been told of 1c, and $1 values. On the reverse of the vales a clause states that notes worth more than one hundred pesos would be paid in the banks of Saltillo or MonterreyEl Imparcial, Tomo XXXV, Núm. 6410, 8 April 1914.

San Pedro

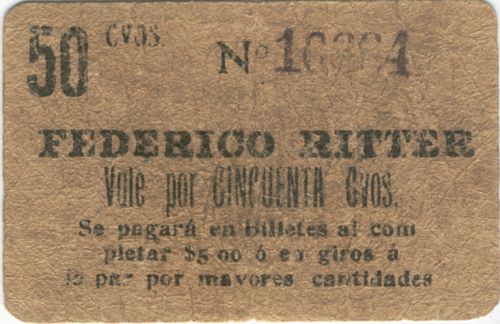

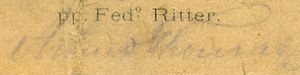

Federico Ritter

M1122 50c Federico Ritter

M1122 50c Federico Ritter

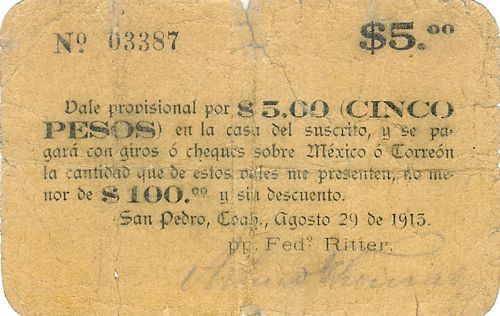

M1124 $5 Federico Ritter

M1124 $5 Federico Ritter

| from | to | total number |

total value |

||

| 50c | includes numbers 2682 to 10394 | ||||

| $5 | includes number 03387 |

Federico Ritter was a German, born in Lerdo on 23 May 1880, and was a businessman (he was an agent for the Banco Nacional de México in Lerdo) and hacendado, owing the haciendas San Ignacio, Santa Lucía and Bolivar in San Pedro.

The 50c note has a blue seal on the reverse with a date in October 1913 and the name HDA DE BOLIVAR, COAHRichard A Long, Mail Auction Sale, July 28, 1975. The $5 note is signed, per pro Ritter, by [ ][identification needed].

|

The low value vales, like those issued by other haciendas, were redeemable in banknotes for $5 or in giros for larger amounts. The $5 notes were redeemable in cheque or giros for amounts of $100 or above, as mentioned in the Mexican Herald article.

This issue was specifically referred to in a query from the Jefe Político of Cuencamé, Durango, on 10 February 1914. The Jefe Político was told by the state government that the issue was not of forced circulation and that it was discussing the matter with the state of CoahuilaADur, Fondo Secretaría General de Gobierno (Siglo XX), Sección 6 Gobierno, Serie 6.1 Acuerdos, caja 1, nombre 3 letter Martín Martínez, Jefe Político, Cuencamé to Secretario de Gobierno, Durango, 10 February 1914. It was also mentioned in the El Imparcial article on 8 April 1914El Imparcial, Tomo XXXV, Núm. 6410, 8 April 1914.

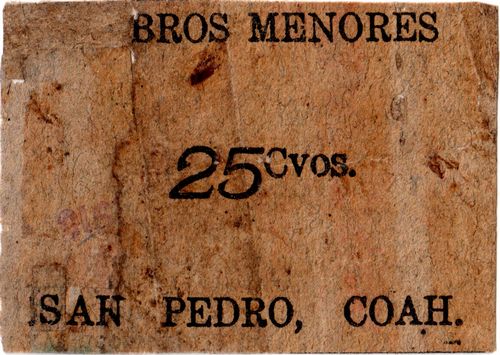

[ ]bros Menores

M1144 25c [ bros] Menores

M1144 25c [ bros] Menores

Note that this denomination, 25c, is not mentioned in the round-up in the El Imparcial article.

Francisco Madero

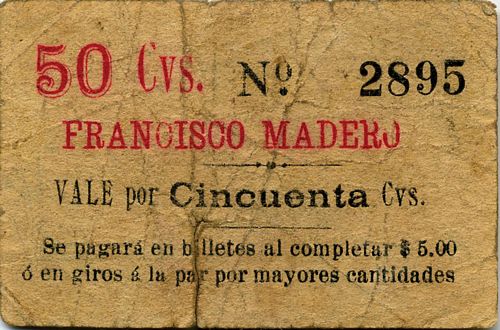

M1146 50c Francisco Madero

M1146 50c Francisco Madero

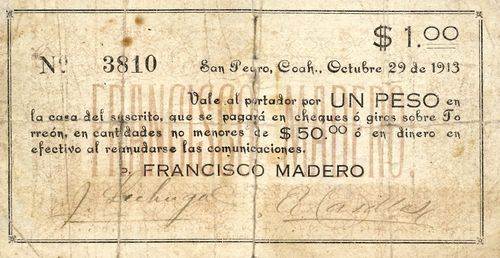

M1147b $1 Francisco Madero

M1147b $1 Francisco Madero

| from | to | total number |

total value |

||

| 50c | includes number 2895CNBanxico #10216 | ||||

| $1 | includes numbers 3343 to 5956CNBanxico #10217 |

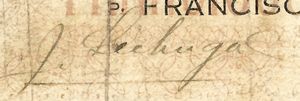

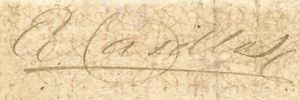

Francisco Ignacio Madero, the future revolutionary, was born into an extremely wealthy landowning family in Parras de la Fuente, Coahuila and in 1893, at the age of twenty, assumed the management of the Madero family's hacienda at San Pedro, Coahuila. These notes were issued by his casa comercial and the $1 note is dated 29 October 1913 and signed by J. Lechuga and E. Casillas.

| J. Lechuga |  |

| E. Casillas |  |

This issue was also specifically referred to in a query from the jefe político of Cuencamé, Durango, on 10 February 1914. The jefe político was told by the state government that the issue was not of forced circulation and that it was discussing the matter with the state of CoahuilaADur, Fondo Secretaría General de Gobierno (Siglo XX), Sección 6 Gobierno, Serie 6.1 Acuerdos, caja 1, nombre 3 letter Martín Martínez, Jefe Político, Cuencamé to Secretario de Gobierno, Durango, 10 February 1914.

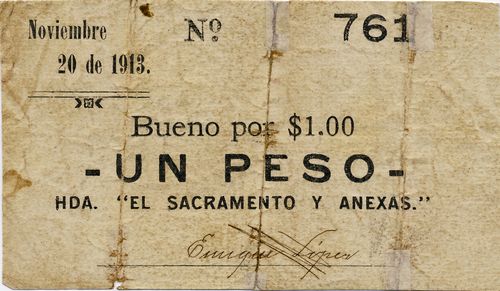

Hacienda “El Sacramento y Anexas”

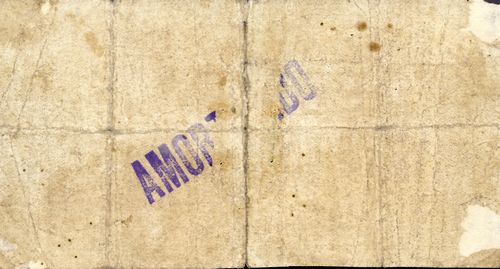

M1143.3 $1 Hacienda "El Sacramento y Anexas"

M1143.3 $1 Hacienda "El Sacramento y Anexas"

| from | to | total number |

total value |

||

| $1 | includes number 761 |

This was issued because of a shortage of small change and would be redeemed when communications were reestablished with Mexico City. It is signed by Enrique López.

| Enrique López |  |

In 1932 Evaristo Madero suggested that a consortium of himself, a friend, Soledad González Dávila, her husband, and maybe Plutarco Elías Calles, should acquire the hacienda that had just passed into the hands of the Comisión Monetaria. ”It is one of the most promising in la Laguna. The area consists of 1,500 hectares of irrigation for wheat and cotton. … Under normal conditions there are profits of 100 to 150 thousand pesos per year. Even more if prices rise”APCalles, Fondo Soledad González, serie 1, caja 11: 1919-1943, exp. 362 letter 22 April 1932.

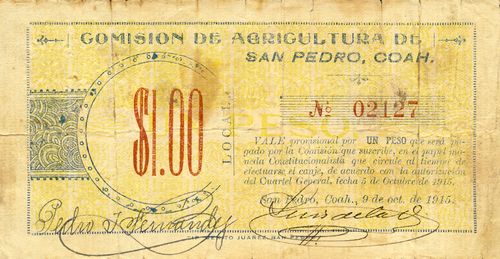

Comisión de Agricultura de San Pedro

M1149 $1 Comision de Agricultura de San Pedro

M1149 $1 Comision de Agricultura de San Pedro

| from | to | total number |

total value |

||

| $1 | includes number 02127 |

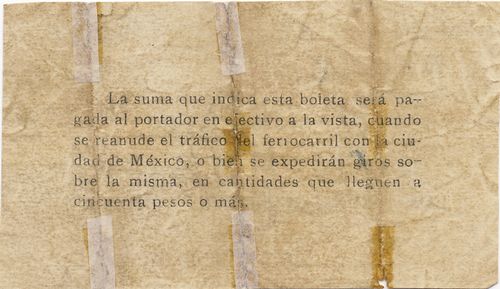

A provisional vale for $1, dated 9 October 1915, to be redeemed in current Constitutionalist money, in accordance with a military accord of 5 October 1915[text needed].

On 28 September 1915 Alvaro Obregón wrote to Carranza, in Veracruz, from San Pedro, asking him to send money in the form of $1, $2 and $5 notes, because their lack, couple with the suppression of Villista currency, was causing serious difficulties. He had borrowed $200,000 from local hacendados but needed around $400,000 to save the situation in the area from San Pedro to TorreónABarragán, caja III, exp. 28. Carranza replied the next day that he had sent $1,500,000 a few days before and would continue sending as much as possible. In the meantime Obregón could authorise the solvent hacendados in the region to issue bonos in the amount that Obregón mentioned and with their backingibid. telegram Carranza, Veracruz to Obregón, San Pedro, 29 September 1915. Presumably Obregón issued the decree mentioned above.

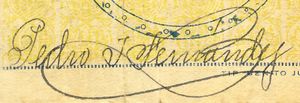

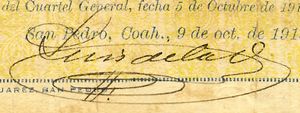

This is a companion note to the Torreón one, though that one predates the military acord. It is signed by Pedro J. Hernández and Luis de la O.

| Pedro J. Hernández |  |

|

Luis de la O was a member of the San Pedro town council in 1908 and representing Francisco Madero in correspondence in December 1910ACoah, Fondo Siglo XX, caja 52, folleto 2, exp. 8. |

|

Parras

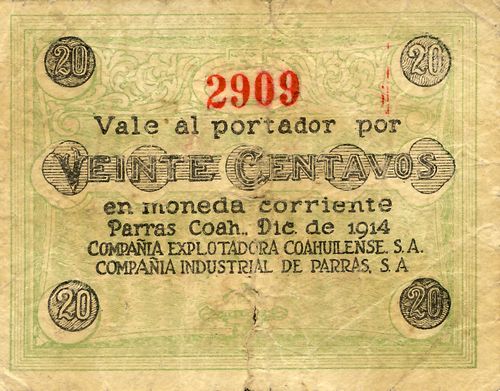

Compañía Explotadora Coahuilense, S. A. / Compañía Industrial de Parras, S. A.

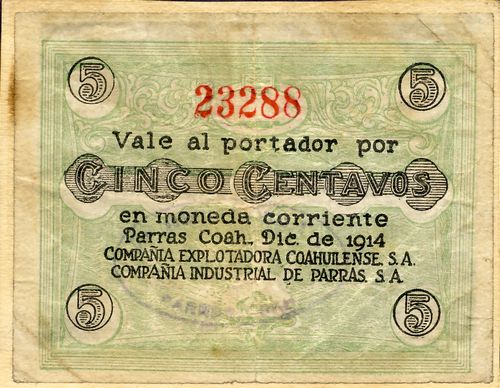

M1136 5c Compañía Explotadora Coahuilense

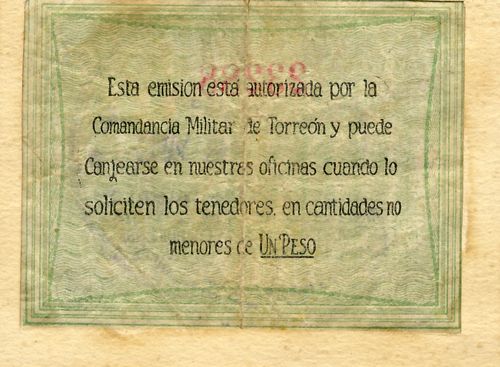

M1136 5c Compañía Explotadora Coahuilense

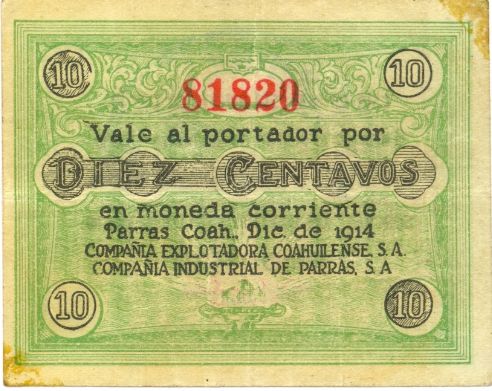

M1137 10c Compañía Explotadora Coahuilense

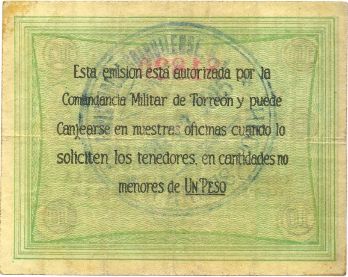

M1137 10c Compañía Explotadora Coahuilense

M1138 20c Compañía Explotadora Coahuilense

M1138 20c Compañía Explotadora Coahuilense

| from | to | total number |

total value |

||

| 5c | includes numbers 23288 to 73294 | ||||

| 10c | includes numbers 67257 to 81820CNBanxico #10215 | ||||

| 20c | includes numbers 2909 to 18265 |

These two companies were part of the Madero empire.

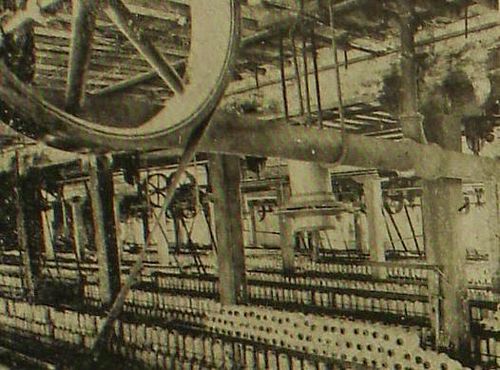

To process the local cotton a textile factory was established on the El Rosario hacienda near Parras in the 1830s (or possibly even earlier). In 1857 the then owners, the Aguirre family, began the reconstruction necessary to install 100 hydraulically powered Danford looms. One of the cotton suppliers, Evaristo Madero, and his son-in-law Lorenzo González Treviño, bought this factory in 1870 and named it Fábrica la Estrella. They remodelled and adapted the buildings and acquired, in 1890, new machinery to replace the previous equipment. La Estrella, the largest textile plant in northern Mexico, turned out cotton textiles such as khaki and gabardine. In 1899 they incorporated the business, which consisted of preparing, spinning, dyeing, weaving, and bleaching cotton and included 350 looms as the Compañía Industrial de Parras. It went on to hold 550 looms and to employ 900 workers.

The factory was expropriated (intervened) during the revolution and when the Madero family regained the enterprise in 1917, it was virtually bankrupt.

The Compañía Explotadora de Parras, which ran a plant for processing guayule (a plant that produces a type of rubber) was also founded by Evaristo Madero.

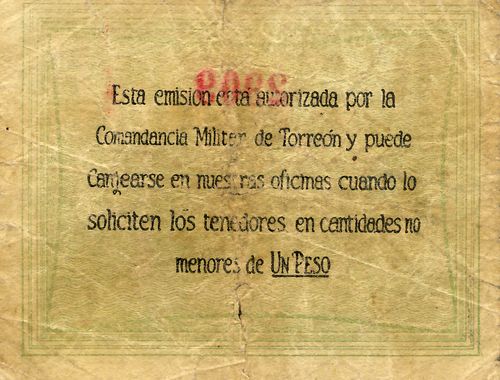

These notes were authorised by the Comandancia Militar in Torreón[text needed]. They are dated December 1914 and were redeemable in the company's offices in amounts of one peso or more.

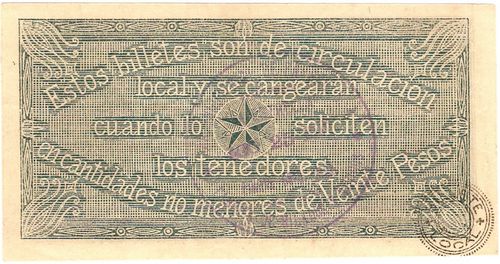

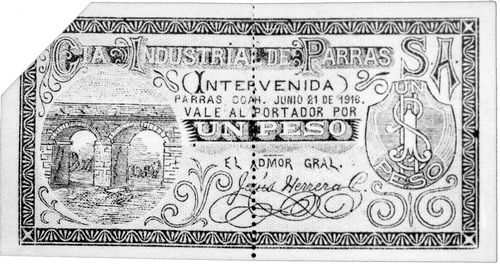

Compañía Industrial de Parras, S. A.

M1139 50c Compañía Industrial de Parras

M1139 50c Compañía Industrial de Parras

M1140 $1 Compañía Industrial de Parras

M1140 $1 Compañía Industrial de Parras

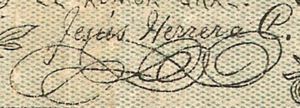

Two rather late notes dated 21 June 1916. once the company had been 'intervened' and signed by the Administrador General, Jesús Herrera, who would have been a government official.

| Jesús Herrera |  |

These were redeemable in quantities of $20. The 50c note has a naive view of the factory and, on a hill, the Iglesia de Santo Madero while the $1 note has a view of the local aqueduct (rather taller than actual).

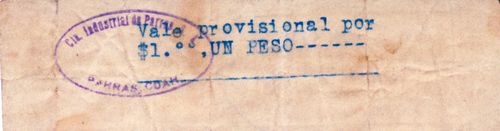

We also have a typewritten vale for one peso from the same period.

M1141 $1 Compañía Industrial de Parras

M1141 $1 Compañía Industrial de Parras

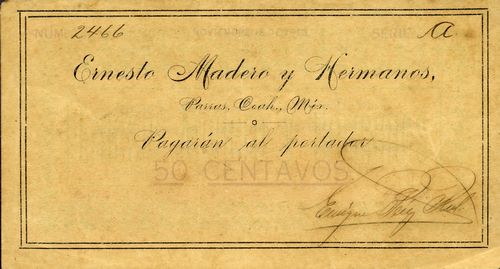

Ernesto Madero y Hermanos

M1143 50c Ernesto Madero y Hermanos

M1143 50c Ernesto Madero y Hermanos

| to | total number |

total value |

||||

| 50c | A | includes number 2466 |

Ernesto Madero managed several of the Madero family companies.

As this note fits the description in the El Imparcial article of April 1914El Imparcial, Tomo XXXV, Núm. 6410, 8 April 1914, it can be dated to before that date. This note is signed by Enrique Pérez Rul.

|

Enrique Pérez Rul was born in the state of Zacatecas, and settled in Matamoros, Coahuila, where in 1908 he was director of the Escuela núm. 1 para Niños. He then became director of the Escuela Primara Modelo in Parras and developed a friendship with the Maderos and the Aguirre Benavides. He joined the revolution with Luis Aguirre Benavides, who served as Francisco Villa’s secretario particular. Enrique Pérez Rul also later served as Villa's secretary and the fact of having been a school teacher allowed him to be the kind of intellectual that Villa respected. He stayed with Villa until the last battle in Sonora and then broke with him and fled to the United States. In 1916 published a pamphlet ¿Quién es Francisco Villa? in which he criticized both Carranza and Villa, but he maintained that the latter was not a bandit and that those who followed him were "men of honour." |

|