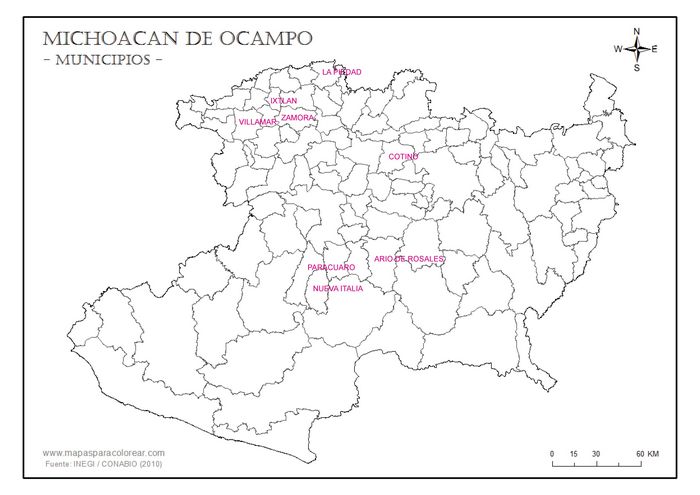

Haciendas (central Michoacán)

Tacámbaro

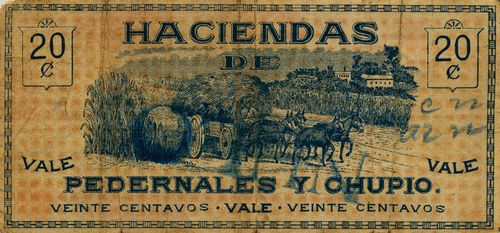

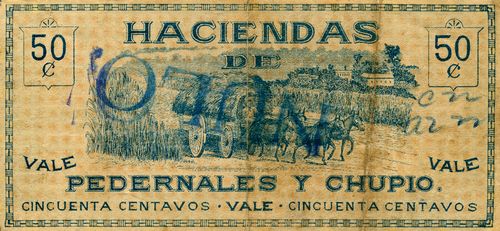

Haciendas de Pedernales y Chupio

Pedernales and Chupio were two adjacent haciendas in Tacámbaro. In 1889 Tacámbaro was the leading area for the production of sugar and aguadiente in the whole of Michoacán. The most productive sugar plantations were Puruarán and Cahulote; the next was Pedernales and the third, Chupio, which was then owned by Teofila León de Ortizmost of this information is from Tayra Belinda González Orea Rodríguez, Estudio Económico de dos Haciendas del Centro de México durante el Movimiento Revolucionario de 1913-1919, UNAM, 20....

Pedernales was owned by Luis Bermejillo, the Marqués de Mohernando. In October 1913 Bermejillo was in Spain and gave Toribio Esquivel Obregón power to administer his haciendas. Unfortunately, at the end of the year Esquivel Obregón was forced to flee the country, handing power to José de la Macorra.

From October 1914 until September 1915 Pedernales was expropriated by the rebel government. José Acha, the administrador, and all the Spaniards were forced to flee and governor Gertrudis Sánchez appointed Luis Mazari as administrador and Manuel Hernández as interventor. With the triumph of the Carrancistas the hacienda was returned to Luis Bermejillo, who designated a new administrator, José Signo. Signo had to deal with the depredations of the rebel Inés Chávez García of the Tercera Brigada Michoacana of the Ejercito Reorganizador Nacional, who stole the sugar intended to pay the wages.

In November 1915, under the advice of José de la Macorra and Toribio Esquivel Obregón, Luis Bermejillo acquired the hacienda de Chupio, which fitted well with the neighbouring Pedernales. The vendor, the Compañía Agrícola de Chupio, at first asked for a million pesos in Carrancista currency, but de la Macorra managed to get this reduced to $850,000, to be paid in shares of the Compañía Minera de Peñoles.

Chupio was returned to its new owner on 29 February 1916. For this Bermejillo had to agree a contract with the Carrancista Maximiano García, by which he had to seld the whole of the sugar cane harvest to the Sociedad M. García for a sum payable in notes of the Banco Nacional de México, Banco de Londres y México or any of the banks recognised by the Constitutionalist government.

Because of the losses he had suffered in 1917 Bermejillo decided to change administradores and appointed Augusto Madriñan. On various occasions Madriñan was in contact with Inés Chávez García to avoid further robberies. Inés Chávez García demanded forced loans and that the hacienda did not export any of its produce, but Madriñan replied that he had no money and also tried to send some of his harvest to the warehouses in Tacámaro, for which Inés Chávez García threaten to come to the hacienda and shoot everyoneUIA, A.T.E.O. S.D, caja 47, exp. 10, fojas 00719-00720. Finally, Madriñan agreed, so for the first months of 1918 Pedernales was practically in the hands of rebels.

Luis Bermejillo returned to Mexico to discover what was happening with his haciendas. In July 1919 he rented the two haciendas of Pedernales and Chupio to the administrador, Augusto Madriñan, thus guaranteeing himself an income as long as the Revolution continuedUIA, A.T.E.O, S.D, cajas 48 and 49, exps. 1 and 9, fojas 00084 and 00255.

The amount the Hacienda de Pedernales paid out in wages in 1918 was around $10,000 a monthJanuary $16,995.75

February 19,425.06

March 18,738.84

April 5,302.57

May 6,087.16

June 7,547.19

July 4,913.06

August 7,920.63

September 8,759.73

October 12,409.01

November 14,218.51

December 13,633.80

Total $135,951.31 (UIA, A.T.E.O, S.D, caja 49, exp. 8, foja 00108).

| to | from | total number |

total value |

||

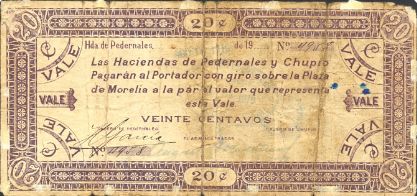

| 20c | includes numbers 2751 to 4958CNBanxico #11610 | ||||

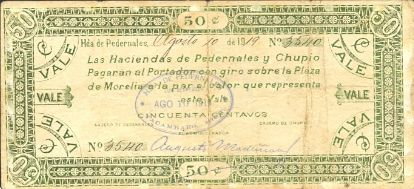

| 50c | includes number 3540CNBanxico #11611 | ||||

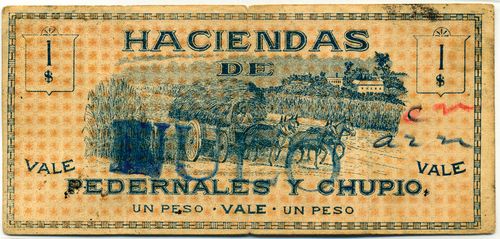

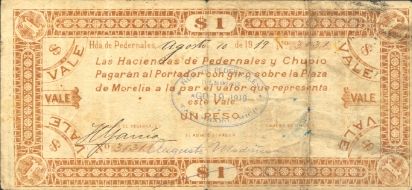

| $1 | includes number 3431CNBanxico #11612 | ||||

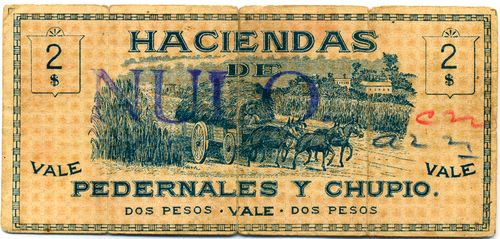

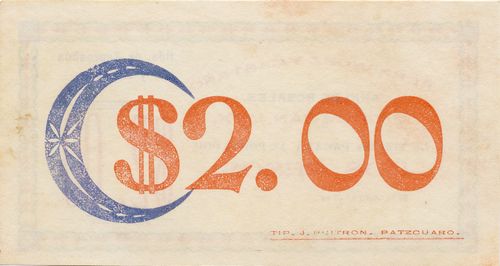

| $2 | includes number 574CNBanxico #11613 |

These rather late notes (known notes are dated 10 August 1919) promise to be redeemable with a cheque drawn on a Morelia bank. Identifiable signatures include H. García as Cajero de Pedernales and Augusto Madriñan as Administrador. There is also space for the Cajero de Chupio who will have signed the notes issued on his hacienda.

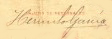

| H. García |  |

| Augusto Madriñan was a Spaniard who administered the haciendas. |  |

In September 1919 Madriñan sent an extensive memorandum to the governor, Colonel Pascual Ortiz Rubio, about the pitiful local defences. Madrinán reported that in the early hours of 3 September Villista parties sent by the commanders Gabriel Fernández and José Zapata arrived at Chupio and demanded fodder for their horses, food for the troops and cash. Having mistreated the employees of the hacienda in various ways, they withdrew a short time later to nearby Potreros. Then, at ten in the morning, the so-called General J. Guadalupe Flores, part of the troops of José Inés Chávez García, arrived. He followed the same course as his predecessors but since the money had been exhausted, it was not possible to give him what he demanded, which displeased him so much that he ordered several employees to be beaten, insulted others, but had to settle for taking only the good found in the tienda, in the absence of hard cash. Meanwhile, a man had left the hacienda for Tacámbaro and gave notice to the captain who commanded one of two outposts established on the outskirts of the town of the presence of the rebels. The captain replied that already knew but had no order to confront themEl Heraldo de México, 22 September 1919.

Ario de Rosales

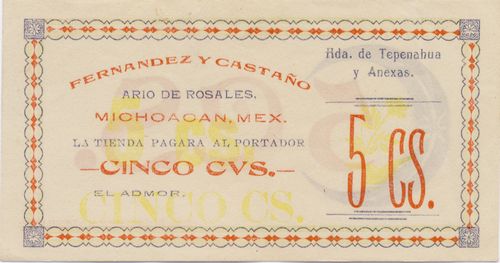

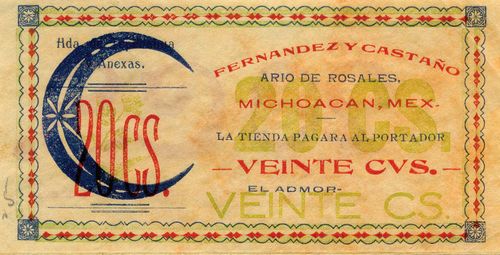

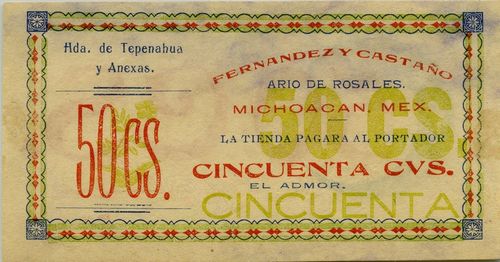

Hacienda de Tepenahua y Anexas

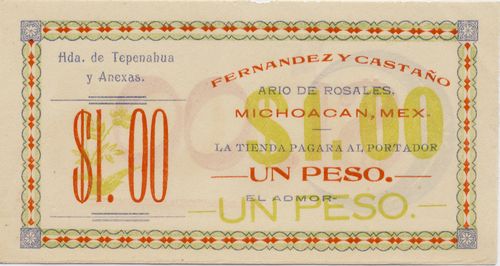

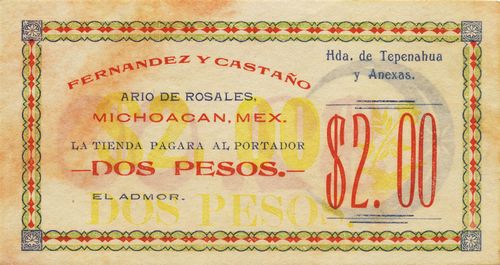

The sociedad Fernández y Castaño ran the sugar plantations, the haciendas Tepenahua and Ibérica until they were broken up in the agrarian reforms.

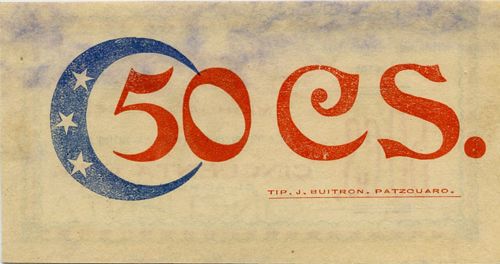

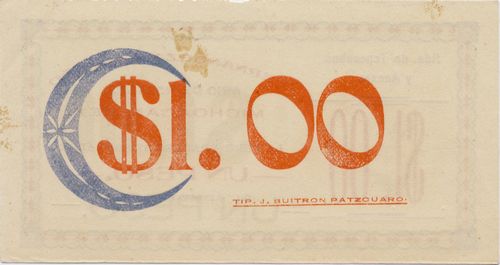

The hacienda de Tepehahua y Anexas produced notes of 5c, 10c[image needed], 20c, 50c, $1 and $2 for use in their tienda. These simple but colourful notes were printed locally by tipografia J. Buitron of Pátzcuaro.

Nueva Italia

Haciendas Nueva Italia and Lombardía

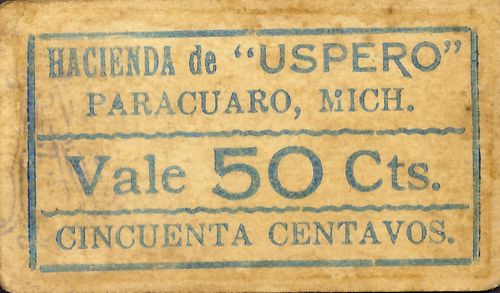

The Italian Dante Cusi arrived in Michoacán in 1884, having emigrated from Lombardy by way of the southern United States, and determined to make a fortune through agriculture. In 1888, Cusi, together with another Italian, Luis Brioschi, formed a company called Cusi & Brioschi, mainly focused on the production and exportation of rice in a ranch that they rented (and later bought) named Úspero in Parácuaro. Their ability and experience in agriculture made them rich in just a year. They split the revenues and started buying land both in Parácuaro and in places around Uruapan. Cusi was determined to build an empire and, no matter what, was going to buy as much land as he could.

The Italian Dante Cusi arrived in Michoacán in 1884, having emigrated from Lombardy by way of the southern United States, and determined to make a fortune through agriculture. In 1888, Cusi, together with another Italian, Luis Brioschi, formed a company called Cusi & Brioschi, mainly focused on the production and exportation of rice in a ranch that they rented (and later bought) named Úspero in Parácuaro. Their ability and experience in agriculture made them rich in just a year. They split the revenues and started buying land both in Parácuaro and in places around Uruapan. Cusi was determined to build an empire and, no matter what, was going to buy as much land as he could.

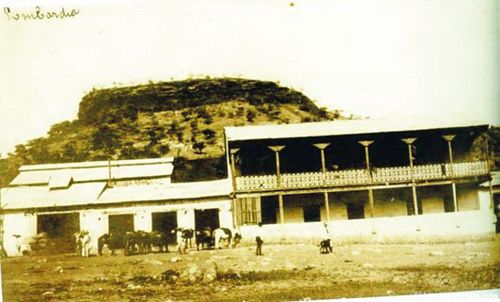

In 1903 Cusi bought the Hacienda de la Zanja, a property of about 69,000 acres, for 140,000 pesos. Together with his sons he gave it a new name: Lombardía, from the region that they came from in Italy. The property was abandoned, with less than 200 people living in their surroundings, but just a few months later, thanks to the investments that Cusi made in the property “not less than 500 families lived on the cascoCusi (1955) Memorias de un Colono, México, Jus, p.89.. They installed a tienda de raya and even a small clinic with a permanent doctor.

Hacienda de Lombardía (1914)

The main activity of the hacienda was the production of rice, but they also produced corn, milk, cheese, and meat products from the 11,000 heads of cattle that they had. They soon diversified, investing in industrial machinery such as a rice mill, a dynamo to produce electricity, a refrigerator for conserving meat, and rice driers.

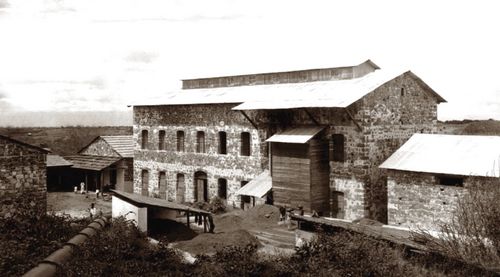

Hacienda de Nueva Italia

In 1909, the Cusi family managed to buy another large estate, the Hacienda el Capirio. This time, they paid 300,000 pesos to the Velasco family, who lived in La Piedad, for the 86,500 acres. Just after the Cusis bought it, they changed its name to Nueva Italia.

The train that connected the haciendas of Lombardia and Nueva Italia (1920)

Their ownership made them powerful and rich. In 1912 they bought a train in Germany Alvarado, Ilia (2018) La “Espantosa Odisea” Italiana en la Hacienda de Lombardía. Una Fuente documental sobre las Haciendas Cusi en Tierra Caliente de Michoacán (1914). Zintzun. Revista de Estudios Históricos #67 to connect both haciendas (Lombardía and Nueva Italia) and they invested thousands of pesos on building the most complex system of irrigation, that changed a land that was almost a desert into the most important productor of cereals in Michoacán. Incidentally, when Cusi, after spending half a million pesos on irrigation works, wanted to use the water of his own estate, Minister of Fomento, Olegario Molina, said, “No,” but “Yes,” if he had the necessary papers drawn up by Joaquín Casasús, - fee, 30,000 pesos.

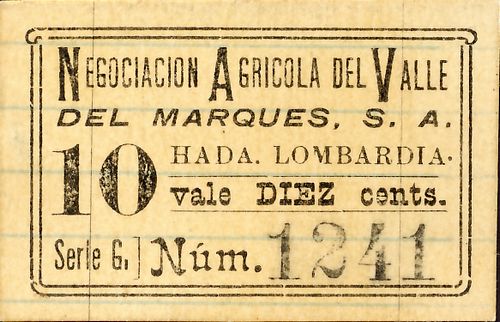

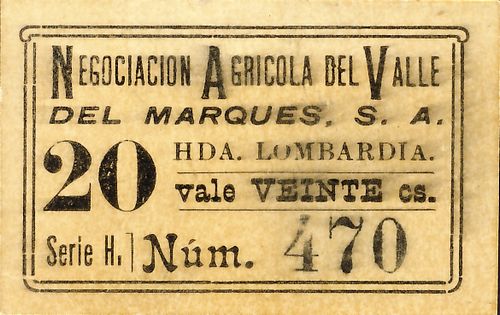

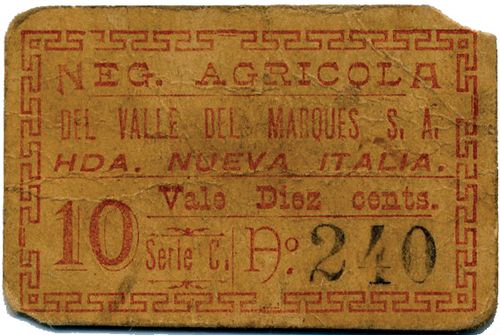

The Cusis formed a Company named “Negociacion Agrícola del Valle del Marqués, S.A.” which they used it to administrate their haciendas and to invest in technology that they imported from the USA and Europe. This company is the one that produced both the notes of the hacienda de Lombardía and the hacienda de Nueva Italia.footnote}The Negociación Agrícola del Valle del Marqués S. A. was established in April 1915 to take over all the debts of the Negociación Agrícola Lombardía y Anexas, S.A. and the assets of the Sociedad Dante Cusí e Hijos S.A. For a detailed history see Jesús Méndez Reyes, “Estragias empresariales en México: La negociación agrícola del Valle del Marqués” in Mario Trujillo Bolio and José Mario Contreras Valdez (editores), Formación empresarial, fomento industrial y compañías agrícolas en el México del siglo XIX, Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social, Mexico City, 2003.

The haciendas manage to survive during the Revolution because the Cusi family had their small army that was able to stop the many attempts of assault that the forces of Cenobio Moreno tried on both the haciendas and because Dante Cusi manage to “buy protection”, giving money to some of the rebels.

The haciendas survived until 1938, when President Lázaro Cárdenas abolished the haciendas, and made the ejidos, a socialist form of organization of the land. The expropriation of the haciendas of Dante Cusi made the Ejido de Nueva Italia the largest one in Mexico.information from Ricardo Vargas, “Paracuaro, a small town in Michoacán with a rich numismatic history”, in USMexNA journal, June 2024.

Hacienda Lombardia

| series | to | from | total number |

total value |

||

| 10c | G | includes number 1241 | ||||

| 20c | H | includes number 470 | ||||

| I | includes number 289CNBanxico #11573 |

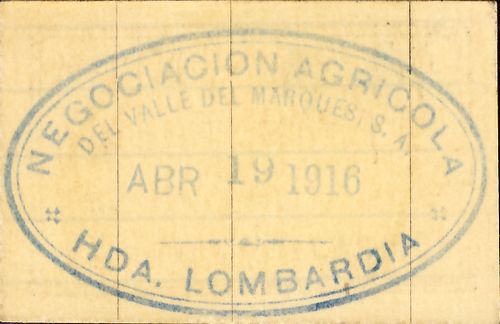

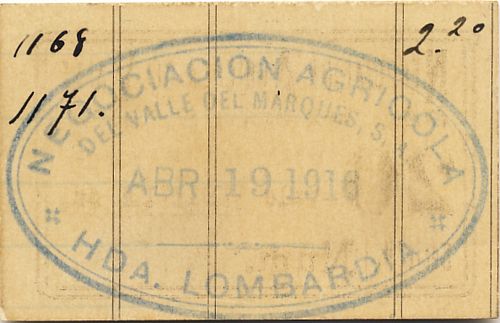

The notes are datestamped 19 April 1916.

Hacienda Nueva Italia

| series | to | from | total number |

total value |

||

| 10c | C | includes number 240CNBanxico #11572 | ||||

| 20c | C | includes number 136 |

Paracuaro

Hacienda de Uspero

This hacienda was also owned by Dante Cusi.

The 10c is dated 12 June 1915 and the 50c 14 July 1915.