The Infalsificables: the last issue of the Constitutionalist government

by Cedrián López-BoschThe author would like to thank the help of Ricardo de León Tallavas, Luis Gómez Wulschner, Roman Guhr, Simon Prendergast, Siddharta Sánchez Murillo and Mark Tomasko in producing this article .

Starting from the second half of 1915, when the Constitutionalist movement seemed to emerge as the triumphant faction of the revolution, the Primer Jefe del Ejército Constitucionalista (First Commander of the Constitutionalist Army), Venustiano Carranza, decided to undertake the economic reorganization of the country, beginning by putting the circulation of money on a definitive basis. For this he suggested putting into circulation a new issue of notes to replace all the previous ones legitimately issued by his movement. With this he intended to unify the currency and define once and for all the exact amount of what he considered a sacred debt contracted by his movement with the Mexican people.

In order to guarantee its success this issue sought to address two shortcomings of its predecessors: to offer a guarantee in gold and to manufacture the notes in a paper of better quality and printed with plates engraved in steel, which would lead the same authorities to call them infalsificables (uncounterfeitable).

However, this effort was premature, fell short and failed to reestablish confidence in this method of payment because, as pointed out by Mónica Gómez and Luis Anaya“El Infalsificable y el fracaso de la establización monetaria en el Carrancismo, México 1916” in Intersticios Sociales, Núm. 8, El Colegio de Jalisco, September 2014, the technical challenges, social pressures and economic shortcomings forestalled it. Although this resounding failure has been widely discussed, the following seeks to explain some lesser-known aspects of the preparation, circulation and withdrawal of this issue.

Antecedents and monetary problems at the end of the revolutionary movement

Between 1913 and 1915, paper money issues had grown exponentially. On the one hand, during Victoriano Huerta’s regime, the banks of issue, either through pressure or voluntarily, had increased the number of notes in circulation, exceeding the limits established in the General Law of Credit Institutions of 1897, in force at that time. On the other hand, the different military factions had issued multiple kinds of paper currency such as notes, bonds and obligations to pay their troops and defray the administration expenses of the territories under their control, without any kind of backing. Finally, faced with the shortage of fractional currency, some individuals, businesses, firms and haciendas had put into circulation other means of payment such as vouchers and cardboard notes, with and without authorization from the political forces prevailing in each region.

To make this situation even more chaotic, as the revolution progressed and the territories passed from the control of some military leaders to others, there followed multiple decrees that declared one or other issue invalid and revalidated others to give them recognition in a specific region. In addition, the growing need for means of payment throughout the country and the shortage of machinery and supplies to produce them gave way to issues made on increasingly simple presses and with lower quality paper and ink, easily making them victims of counterfeiting. As Gresham’s Law Sir Thomas Gresham’s law (bad money drives out good) holds that when two currencies have legal tender the one composed of the more valuable metal will be hoarded and replaced by the one of less valuable metal, which will continue to circulate. supposes, this multiplicity of paper currency, without any backing, caused the hoarding or export of gold and silver coins, making them disappear from circulation.

With the Provisional Government issue, issued in Mexico and Veracruz, Authorized by a decree of 19 September 1914. The Mexico issues are dated 28 September and 20 October 1914 and the Veracruz issues 1 December 1914 and 5 February 1915 Carranza had expressed his intention to achieve uniformity in the means of payment and to allow holders to distinguish notes that had legal tender from those that did not, by exchanging the notes issued earlier for them. However, in the country a myriad of authentic and false issues circulated, as previously described, including counterfeits and reproductions of those same issues of the Provisional Government, some of them printed with the original lithographic plates left in Mexico City when the Carrancista troops moved the capital to Veracruz Although known references to these issues point to impressions made in the state of Morelos (vide Elmer Powell ‘’The Provisional Government of Mexico issues (Mexico and Veracruz)” in USMexNA Journal, March 2014), in October 1915 the Constitutionalist consul in San Francisco, Ramón P. de Negri wrote to Venustiano Carranza asking about a possible theft of plates, due to the presence in that city of an individual with a Spanish passport named Cecilio Herero, with instructions from Hipólito Villa to make impressions to put into circulation in the territories occupied by Villista troops (CEHM, Fondo XXl-4 Archive of Venustiano Carranza, telegram of de Negri to Carranza, 21 October 1915). Surely there were multiple counterfeits as there were multiple legitimate printings of these notes..

However, the disorder was not only outside, but also within the Constitutionalist movement itself. Besides anecdotes of abuses by officials of the Treasury or Revenue offices who were in charge of exchanging or revalidating issues, a report sent on 15 June 1915 by Álvaro Pruneda described an absolute disorganization and discontent in the same Treasury Printing Office and serious deficiencies in the Verification Department of the Treasury in charge of identifying counterfeits Summary presented to Carranza (CEHM, Fondo XXI Archive of Venustiano Carranza, 43.4641.1-2). A more complete version must have been presented to the Minister of Finance, Luis Cabrera.. This study, in addition to the administrative measures necessary to improve the efficiency and control of both offices, recommended implementing a series of advanced measures against counterfeiting, particularly striking in the armed context, through the preparation of:

III ... a new issue of paper currency, as if it were from a State Bank, with the following defenses against all forgery:

a) Paper of special manufacture with a watermark and a combination of silk threads in the pulpthis, and other queries, addressed in a response from the ABNC on 2 September 1915 (ABNC, folder 210, Republic of Mexico (1915 (Feb) – 1916 (June))

b) The inks used must have special reagents in their preparation

c) The engraving should be the most original and protected by technical difficulties

d) Invisible security marks so that photographs cannot be taken and which can only be discovered by a special procedure

e) A combination of progressive or logarithmic numbering

f) A special register of circulation.

IV. For this issue, to produces notes of only $5, $10, $50 and $100, carefully printed on a press directly from steel sheetsibid..

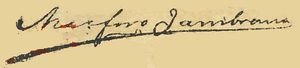

To bring about this situation and solve the problem of counterfeiting, on 21 July 1915, Carranza issued a new decree which authorized the issue of 250,000,000 pesos in banknotes. With this amount he intended to replace all the notes in circulation issued by the Constitutionalist Government and his military commanders with others, following the suggestion of Pruneda, “of an artistic perfection such that its falsification was not possible” and “to meet the needs of the government, thanks to the increase in the national debt”. The denominations of this issue were to be 5, 10, 20, 50 and 100 pesos, and all of them would have the signatures of the General Treasurer, Nicéforo Zambrano and Rafael Nieto, Undersecretary in charge of the Treasury Secretariat, the office responsible for fixing the series, numbers, marks and countermarks, as established by the decree.

A few days later, in an interview for the official newspaper El Pueblo, Undersecretary Nieto described this issue as a “true artistic novelty. [Because] neither the Government, nor any of the issuing banks in Mexico, had printed notes of such fine quality as those of the new issue that is being prepared," and added:

“The new notes will be printed by the most prestigious American firm dealing in this matter, and the best materials that exist will be used in them. The paper to be used is cellulose on a thread base, with a special watermark. The finest inks and the least common colors will be used.

The engravings, designs, security marks, edges and borders will be entirely original, having on the faces multi-colored geometric engravings, very novel and artistic, as an absolute proof against counterfeiting.

The reverses will probably contain the beautiful and severe Aztec calendar. The faces will show carefully chosen designs: the Faros building, the monuments to Juárez and Cuauhtémoc in Mexico City, and others.

For the general ornamentation, borders, edges, etc. the ruins of Uxmal have provided exquisite ideas”“Los billetes de la Nueva Emisión. El Señor Sub-Secretario de Hacienda da detalles acerca de su factura”, El Pueblo, Año II, Tomo II, Núm. 352, 25 July 1915; El Dictamen, Veracruz, Tomo XVII, Núm. 1564, 25 July 1915.

Surely, to give these details, the negotiations with the chosen American printing house, which could not be other than the American Bank Note Company (“ABNC”), should have been well advanced and probably had already seen some models. How would that have been possible? In his memoirs, former President Pascual Ortiz Rubio tells that he was commissioned to direct and monitor the printing of these notes Pascual Ortiz Rubio, Memorias (1895-1928), México, Academia Mexicana de Historia y Geografía, serie Divulgación Cultural Vol. 3., p 54.. He already had some experience in the matter: in 1914 he had worked under the orders of Alberto J. Pani in the Stamp Printing Office as responsible for applying seals to the Constitutionalist notes in Ciudad Juárez, and when the capital of the Provisional Government was installed in Veracruz, at the end of that year, he had taken over the transfer of the presses and matrices of the Printing Office of the Government in Mexico City to that state, being responsible for establishing and directing a Note Printing Office in the port.

At the beginning of February 1915, the Secretary of the Treasury, Luis Cabrera, sent him to manage the printing of Constitutionalist notes in the United States. Ortiz Rubio arrived in Washington and from there moved to New York where he met with three printers specializing in engraving paper money, the ABNC, the New York Bank Note Company (successor to the Kendall Bank Note Company, which had already produced some issues for Mexicoprivate issues for Stallforth, Alcazar & Compañía of Guanajuato and Patricio Milmo of Monterrey) and the Hamilton Bank Note Company, as well as three paper mills, National Paper, Grane (sic) Obviously a reference to Crane, the company that provided paper for US banknotes and Parsons. As reported to Carranza, the companies that responded best to Secretary Cabrera’s instructions regarding delivery time, quantity and price were the New York Bank Note Company and Parsons. “ Report of lng. Pascual Ortiz Rubio, to Venustiano Carranza, of the result of the commission conferred by Luis Cabrera to manage the printing of Constitutionalist notes, in the city of New York", in Isidro Fabela (comp.), Documentos Históricos de la Revolución Mexicana XVI, Revolución y Régimen Constitucionalista, Tomo 1, Volumen 4, Comisión de Investigaciones Históricas de la Revolución Mexicana, Editorial Jus, México, 1969, pp.101-104. Taking advantage of his relationship with lithographic printers, Ortiz Rubio immediately signed a contract with the latter for the printing of one and two peso notesABarragán, caja 3.3 exp. 24 (2), that is, not the infalsificable but still the Veracruz issue, to meet the demand for low denomination currency to pay the troops and sustain commercial activities in most of the territory controlled by the Constitutionalists, given the inability of the Printing Office in Veracruz to supply them. However, Ortiz Rubio ended up selecting the ABNC to perform, at this time, the printing of the infalsificable notes, negotiating the contractConfer CEHM, Fondo XXl-4 Telegrams of Luis Cabrera to Carranza, 18 and 23 August 1915 (vide infra), approving the designs and supervising the works. For personal reasons – the illness and death of his mother - Ortiz Rubio left this task to Jorge U. Orozco, and then, according to his account, to the consul and financial agent in New York, Dr. Alfredo Caturegli. CEHM, Fondo XXl-4, Telegram of Carranza to Luis Cabrera, 25 February 1916: 17. CEHM, Fondo XXI, 69, 7570 1; 18. Another character also involved was Luis Montes de Oca, who would be appointed Secretary of the Treasury a little more than a decade later..

Planning the issue

Parallel to the design and printing, it was necessary to plan the introduction and adjust it to the delivery times. In mid-October 1915, Undersecretary Nieto informed Carranza of a delay in the delivery of the notes until the end of December, as reported by Ortiz Rubio and Caturegli, disrupting plans to announce an increase in the total national debt contracted with this new issue CEHM, Fondo XXl-4 Telegrams of Rafael Nieto to Carranza, 16 and 19 October 1915. Nieto rejected Caturegli’s suggestion to print lithographed notes, but he was considering the possibility of printing another 250 million “with another credit house (sic) similar to the American Bank Note Company even if it had the disadvantage that the issues from both houses were not exactly the same” CEHM, Fondo XXl-4 Telegram of Rafael Nieto to Carranza, 19 October 1915. Carranza responded by accepting the suggestion, ”taking care to notice that the engravings (sic) of the notes are different to the model that the American Bank Note [Company] has made” CEHM, Fondo XXl-4 Telegram unsigned to Rafael Nieto, 24 October 1915. The resolution of this matter, as indicated in Carranza’s telegrams, must have been a meeting between both officials, so the reason for not printing them in another printing house is unknown.

With the passage of the months the expenses of the Constitutionalist movement increased. Perhaps the delay in putting this issue into circulation justified, in part, the increasing amounts of Provisional Government notes in Veracruz that far exceeded the authorized amount. This made it necessary, as Undersecretary Nieto had anticipated months before, to increase the total amount of the debt again. To this end, on 25 February 1916, Carranza instructed the Ministry of Finance and Public Credit to take the necessary measures to fix and raise the value of the currency of the Constitutionalist Government; recognizing and defining the total amount of the debt contracted with the Mexican people; creating a guarantee fund; ensuring autonomy in the management of finances; preserving the interests of the people over those of banking, industry and commerce and looking for ways to prevent counterfeiting Venustiano Carranza, 25 February 1916, in Manero, La Reforma Bancaria en la Revolución Constitucionalista, México, 1958, INEHRM., pp 206-209.. So, on 3 April 1916, Carranza issued another decree in Querétaro setting at 500 million pesos the amount of public debt, in the form of fiduciary currency, and instructing the said Ministry to put it into circulation as of 1 May. Similar to the July decree of the previous year, he pointed out that they should be printed on special paper as infalsificable. The following table details the amount of notes and face value of both decrees:

| Table 1: Constitutionalist decrees referring to the issues of the infalsificables | ||||

| 21 July 1915 | 3 April 1916 | |||

| Denomination (pesos) | Quantity | Total value (pesos) | Quantity | Total value (pesos) |

| 1 | 50,000,000 | 50,000,000 | ||

| 2 | 25,000,000 | 50,000,000 | ||

| 5 | 10,000,000 | 50,000,000 | 10,000,000 | 50,000,000 |

| 10 | 5,000,000 | 50,000,000 | 5,000,000 | 50,000,000 |

| 20 | 2,500,000 | 50,000,000 | 5,000,000 | 100,000,000 |

| 50 | 1,000,000 | 50,000,000 | 2,000,000 | 100,000,000 |

| 100 | 500,000 | 50,000,000 | 1,000,000 | 100,000,000 |

| Total | 19,000,000 | 250,000,000 | 98,000,000 | 500,000,000 |

That new decree doubled the authorized amount authorized on 21 July 1915 and included one and two pesos denominations but did not give more characteristics. To put them into circulation, on 4 and 5 April, Carranza created a Monetary Commission, empowered to “collect, conserve and administer the funds designated by the Government to regularize and guarantee internal circulation within the country and to serve as a conduit for the issue and withdrawal of currency issues” and a Regulatory Fund to guarantee the circulation of this currency.

On the 28th of that same month Carranza issued two new decrees; one to indicate the issues to be withdrawn and the terms on which they would be withdrawn, and another to launch this infalsificable issue into circulation, with a backing in national gold of 20 centavos per peso. Unlike previous issues, they would not exchange old notes for new, but, instead, the infalsificable currency, in seven denominations (1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50 and 100 pesos), would enter circulation through all payments made by the federal and local governments - including salaries - and the old paper currency (the Ejército Constitucionalista and Veracruz issues) would continue to circulate without limit and would be decommissioned when paid in to public offices, either for taxes or services. Another twenty issues made by the main military and civilian leaders, recognized by the Constitutionalist movement, were to be deposited in the Ministry of Finance, Treasury and Revenue offices for their subsequent exchange. The 20, 50 and 100 peso notes of Veracruz would stop circulating on 6 June, although they could be deposited in these offices during the months of June and July in exchange for national gold certificates, again for their subsequent exchange, and those of 1, 5 and 10 pesos would be valid for private transactions until 30 June, although they would be received in payment of taxes until the end of 1916.

Although the seven denominations of one to one hundred pesos are part of the same issue, it seems that they are of two completely different sets, since they were made by different factories, with different printing processes and based on different decrees. The $5 to $100 notes were printed in New York by the ABNC with plates engraved in steel, bear the title of “República Mexicana - Gobierno Constitucionalista“, lack a date and were issued based on the decree of 21 July 1915. The two lesser denominations were produced in the Government Printing Office of Mexico, bear the same title of the previous issues, that is, “Gobierno Provisional de México”, are dated 1 May 1916, and were put into circulation as the result of a decree of 3 April 1916. All were signed by the Treasurer General, Nicéforo Zambrano and the Undersecretary of Finance, Rafael Nieto.

Although in the numismatic field only those of the ABNC are known as infalsificable, as all were put to circulation as part of the same issue and the Carrancista government referred to both types as infalsificable currency, I will consider it so in this article.

For the ABNC negotiations and issues, see here, and for the $1 and $2 notes printed in Mexico, see here.

Security measures

The Revolution was a period in which there were intrigues and plots, so many of the communications, including several telegrams on the issue of paper money, were made in an encrypted manner and it seems that some of these peculiarities were introduced as security codes on the notes. The infalsificables printed by the ABNC seem to have the intention of forming the word “Mexico” with the letters of the series (100 pesos M, 50 pesos E, 20 pesos X, 10 pesos I, 5 pesos C). It is not known if at the time an additional denomination of two or one peso with the series O was considered to complete the word, although it was not considered in the first decree.

The ABNC notes had special countermarks and on 27 July 1916 Cabrera requested a specimen of each of notes, showing the secret marks embodied on each note. “His reason for asking for these secret signs is that many people who wish to depreciate the new paper currency are circulating the report that the notes were never printed by the A. B. N. Co. of New York but were printed in Madrid, Paris or London, and that they already many counterfeit notes in circulation. One friend of the Ministers took him a note, which he said was false, and which he claimed was one of many which were being sold cheaply on the border. The Minister told me that the note was perfectly genuine, and that he had offered his friend that he would buy as many of these notes as he could get, at the price he had mentioned.

All this comes from the fact that the imprint on the notes you printed reads: - American Bank Note Company - whereas the imprint on the old bank notes of the Republic of Mexico reads;- American Bank Note Company of New York. A small difference truly but one which has caused a great deal of talk.”

In the case of banknotes printed in Mexico, in addition to the serial letter, all have a second letter. Due to the reduced number of series issued from the notes of the so-called Tlaxcala Congress, I have not identified if there was an intention with those letters. However, the one peso notes with the vignette of the Tenochtitlán legend form the word “INDOMABLES” when the ten series that go from the letter L to the U are joined and read in reverse.

Entry into circulation

The decree of April 1916 ordered the Ministry of Finance to put the notes of the new issue in circulation on 1 May. The notes printed by the ABNC had begun arriving in Mexico from December 1915 and according to El Pueblo the printing of the two lowest denominations began in March 1916“El Banco Nacional mejoró ayer el tipo abierto por la Comisión de Cambias y Moneda”, El Pueblo, Año III, Tomo I, Núm. 522, 2 April 1916. Although at the beginning of April Carranza had instructed the Printing Office to concentrate on this issue“Se suspenderán en absoluto los trabajos de emisión del actual papel moneda. La Oficina Impresora de Estampillas, se concentrará a preparar lo relativo a la nueva emisión de billetes por valor de uno y dos pesos”, El Pueblo, Año III, Tomo I, Núm. 525, 5 April 1916 only the ABNC notes went into circulation when paying public employees their salaries for the first ten days of May.

On 10 May Blackmore, the ABNC's Resident Agent in Mexico, reported that ““The new issues are now in circulation in small quantities. The method employed for the circulation of these notes is by paying the Government officials and employees, including the army, their salaries and wages in the new notes, and the Government is taking up the Vera Cruz notes now in circulation by accepting them in payment of taxes and railroad fares and all payments due to the government. This is of course a very slow way to change the issues. Taxes have all been increased 100% and export and import taxes have been placed on a Mexican gold basis, the Mining taxes are now also collected on a gold basis. The stamp taxes have been doubled and in some cases even increased more than 100% when payments are made in gold.

The new paper currency is issued at the rate of 20 cents Oro Nacional (Mexican Gold) to the peso, this rate should of course make the rate on New York at 10 cents U.S. gold per peso for the new notes. But at present no one knows what is going to happen with regards to the rate at which the Veracruz notes are to be taken in exchange for the new issue. The exchange on Veracruz notes is today at .027 cts approximately, as the rate fluctuates hour by hour - and it rises or drops several points each day.”ABNC, folder 210, Republic of Mexico (1915 (Feb) – 1916 (June).

Despite working flat out, the new one and two peso notes were not released until the beginning of June, forcing the authorities to announce, as a temporary and emergency measure, the acceptance of $1 and $2 notes of the Gobierno Provisional issue and the fractional currency at half its value, as long as they were for transactions for less than five pesos“Seguirán circulando los billetes de uno y dos pesos y la moneda fraccionaria”, El Pueblo, Año III, Tomo I, Núm. 546, 30 April 1916, generating great confusion.

Speculators, commonly known as coyotes, quickly appeared on the scene offering employees the chance to exchange their infalsificable for notes of the old issues that allowed them to make low value purchases, while they rushed to turn them into gold at the rate of 20 percent as established by the government. To avoid abuses the period for circulation of the three higher denominations was reduced to 30 June, while in the absence of new low-value notes, the old ones of $5 and $10 circulated until 3 June, and the use of the $1 and $2 paper money was extended on three separate times until 31 January 1917. Bertha Ulloa, Moneda, Bancos y Deuda in Historia de la Revolución Mexicana, Vol. 6, p. 166. All this complicated the introduction of the infalsificable currency, since the first days there were no low denomination notes and then they were not enough, causing discomfort to the population, commerce and even the military commanders and local governments throughout the country, who asked Carranza to send them new notes and/or continue accepting those that should have stopped circulating.

Although the introduction would not officially be done by direct exchange, some references seem to indicate the opposite, such as a report on 15 June in Monterrey that said that the State Treasury and the Treasury Department were initiating the exchange of notes and cartones of the old issue for the new ones“Notas de Monterrey: Quedó abierto el canje para toda clase de billetes y cartones de la vieja emisión”, El Pueblo, Año III, Tomo I, Núm. 594, 21 June 1916. Meanwhile, the collecting and amortizing offices sorted the notes withdrawn from circulation and prepared them for incineration.

In spite of the decrees to force all transactions in this currency and the threats and sanctions of the Government“Los billetes de uno y dos pesos no deben sufrir descuento”, El Pueblo, Año III, Tomo I, Núm. 727, 7 November 1916 distrust grew and contrary to expectations, the monetary reserves did not grow but ran out, forcing the authorities to suspend conversion into gold.

This gave way to a rapid depreciation of the infalsificable currency. At the beginning of June, Carranza informed the governors of the states that the exchange rate between the infalsificable paper and the old issues was already four pesos of the old issues to one infalsificable, and on the thirteenth of that same month the rate had devalued to a ratio of 10 to oneCEHM, Fondo XXl-4, telegrams of Venustiano Carranza to governors of various states, 2 and 13 June 1916. Starting in October, the Ministry of Finance would set the rate weekly and by the end of the year it was less than half a centavo. This depreciation forced the government to demand from the states and from the population at large that the payment of duties and taxes be made in increasing proportions of gold, in silver or its equivalence in infalsificables at the rate of exchange defined by the Ministry of Finance. KemmererEdwin Walter Kemmerer, Inflation and Revolution: Mexico's Experience of 1912-1917, p. 196 gives the exchange rate (U.S. cents for peso} in New York for June to December 1916:

| maximum | mínimum | average | |

|---|---|---|---|

| June | 9.70 | 9.70 | 9.70 |

| July | 9.70 | 9.70 | 9.70 |

| August | 4.25 | 3.10 | 3.80 |

| September | 3.45 | 2.75 | 3.11 |

| October | 2.775 | 1.75 | 2.32 |

| November | 1.90 | 0.45 | 0.99 |

| December (1-4) | 0.50 | 0.37 | 0.46 |

Naturally the reaction was immediate and employees, laborers, and workers began to demand payment in metallic currency. In response, on instructions from Carranza the Ministry of Finance ordered that salaries and wages be paid at least 50 percent in silver and the rest in infalsificable at a rate of exchange defined by the Treasury, although the salaries of the federal employees would be met by a separate special provision that would be issued in a timely fashion. At the beginning of December federal employees were still paid 95% in infalsificable and 5% in coin, but as of 1 January 1917 troops stopped being paid in infalsificables.

The notes printed in Mexico had even worse luck. As Blackmore had pointed out, some merchants rejected them or took them at a discount. Greater confusion still generated the circulation of the two peso notes with and without the legend of “provisional circulation”, which led the Treasury Secretary to have to clarify through the press and later through a circular that both were equally validEl Pueblo, Año III, Tomo I, Núm. 704, 15 October 1916 and circular 275 of the Ministry of Finance, 9 November 1916, stating that $2 notes with the legend “Circulación Provisional” across Serie A were legal tender.

On 2 December Carranza arranged that some contributions that were previously paid in infalsificable should be paid in part or in total in national gold, sealing the fate of this paper money. Immediately the circulation of metallic currency was re-established and its export allowed.

Withdrawal from circulation

On 29 March 1917, the demonetization of these notes was decreed and, to remove them completely from circulation, a decree[text needed] was issued on 25 April, that from 1 May everything that carried import and export duties on the production of metals, would have a surcharge of one peso infalsificable for each peso or fraction in national gold, with which they would be withdrawn from circulation, and on 28 April circular 61 on deposits made in infalsificable in rent payments was issued[text needed]. At the beginning of September, in his report to Congress, Carranza stated that $20,110,669.45 had been incinerated and that the Comisión Monetaria had $219,762,484.62 more to incinerateEl Pueblo, 4 September 1917: Periódico Oficial, Tomo XLII, Núm. 75, 19 September 1917.

In January 1918 it was resolved that all the federal offices of Hacienda should regularly send their stocks of infalsificables to the Comisión Monetaria for it to be incinerated. Over $300,000,000 had already been retiredEl Pueblo, Año III, Núm. 1156, 11 January 1918. In the minutes of this Comisión Monetaria, in August 1918 almost 300 million pesos in infalsificables had been incinerated and as of 31 October 1919 the amount had grown to almost 363 millionBy 25 April 1919 Eduardo del Raso, the manager of the Comisión Monetaria told Blackmore that the Government has up-to-date cremated $339,000,000 of infalsificable notes (ABNC, folder 210, Republic of Mexico (1915 (Feb) – 1916 (June)). Finally, in the report to Congress on 1 September 1920 de la Huerta said that there were still almost 107 million pesos in circulation.

Almost a million of infalsificables escaped being incinerated and appeared in Mexico’s treasury a century later .

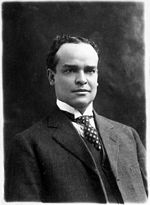

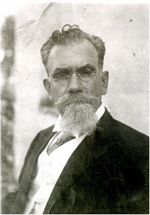

José Nicéforo Zambrano Cavazos was born in San Nicolás de los Garza, Nuevo León, on 22 February 1861. He joined the revolution during Madero’s campaign and at its triumph had been elected president of the Monterrey town council. He was imprisoned during Huerta’s regime but on release supported Carranza, both against Huerta and then against Villa.

José Nicéforo Zambrano Cavazos was born in San Nicolás de los Garza, Nuevo León, on 22 February 1861. He joined the revolution during Madero’s campaign and at its triumph had been elected president of the Monterrey town council. He was imprisoned during Huerta’s regime but on release supported Carranza, both against Huerta and then against Villa.