Examples of scrip used by companies from Sonora to pay their employees are rare. First, no one had any incentive to leave scrip behind: the employees would not regard it as a store of value for any time longer than the period between paydays, whilst employers, to whom scrip was an outstanding obligation, would redeem it first if they liquidated, merged, or closed down their operations. In addition, everyone was aware of its questionable legality{footnote}Among other dispositions payment by means of tokens was prohibited by presidential decrees of 30 November 1889 and 25 March 1905{/footnote}.

Though free labour existed in the north of Mexico, on Sonoran haciendas and ranchos the predominant form of labour remained debt peonage. To ensure employment and a suitable dwelling and to acquire goods, many Sonorans, with no physical coercion, willingly offered themselves as peones and became indebted. Most labourers, Mexican or Yaqui, received payment in kind: one observer commented that remuneration for labourers consisted of ‘goods and food like sugar, beef, liquor, cloth, or whatever else the foreman wishes’{footnote}Cyprien Cornbier, Voyage au Golfe de California, Paris, 1864{/footnote}. To ensure the indebtedness of the peones, the owner charged as much as three times the original value of most goods{footnote}John Denton Hall, Travels and Adventures in Sonora; containing a Description of Its Mining and Agricultural Resources and Narrative of a Residence of Fifteen Years, Chicago, 1881{/footnote}, so the people seldom managed to pay off their original debts, and the operators could be assured of a relatively stable labour force.

In larger cattle- or wheat-producing enterprises, where hacendados regularly needed labour, this relationship proved advantageous to both groups. The landowners acquired a dependable work force, and the labourers, shelter and basic goods. After several generations, some hacendado-labourer relations acquired a degree of familiarity and mutual trust, decreasing the use of coercion. Wealthy hacendados and merchants, such as the Camou family, maintained a permanent number of indebted peones. On outlying smaller ranches, where labour remained scarce, coercion became the rule, especially where indigenous labour was involved. In the northern countryside of Altar and Arizpe, ranchers resorted to brutality to maintain a stable labour force and hunted down escaping workers like runaway slaves.

In 1883 the Sonoran state legislature limited debt to the equivalent of six months labour. Labourers now had the opportunity to seek employment on the American side of the border or in large foreign-owned mining enterprises within Sonora, and formal peonage gradually lost ground, though it continued into the early decades of the twentieth century.

Hacienda tokens from Sonora date from the colonial period{footnote}Cf. O. P. Eklund and S. P. Noe, Hacienda Tokens of Mexico, New York, 1949; Erma Stevens, Privately issued Storecards and Tokens, State of Sonora, Mexico, 1970; Claudio Verrey C., Fichas de Sonora, Mexico, no date. For later tokens see here{/footnote} but no examples of the use of a distinct paper currency are known.

| from | to | total number |

total value |

||

| 12½c | includes number 2346 | ||||

| 25c | |||||

| $1 | includes number 3515 |

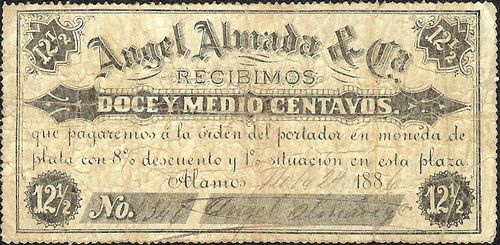

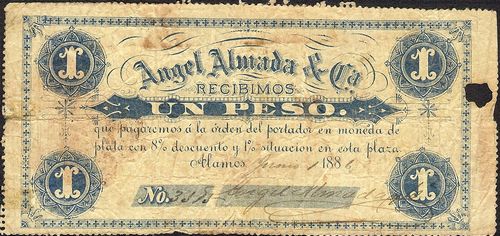

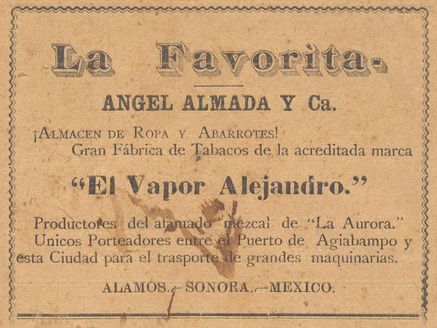

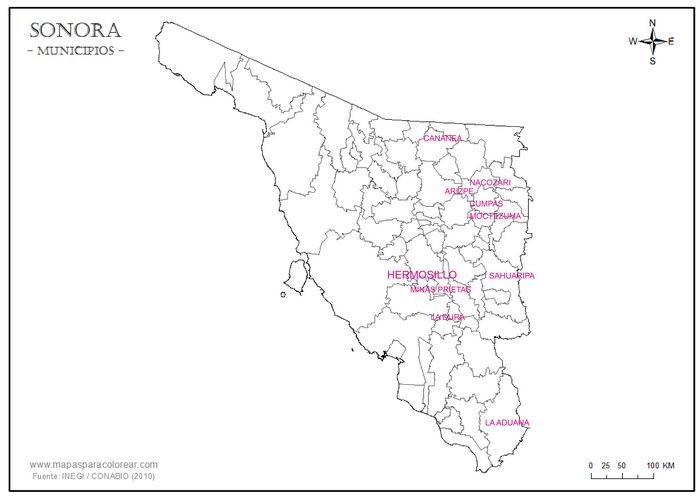

The earliest known paper currency, issued as a substitute for the scarce coinage, is dated 1886. These are three notes (12½ and 25 centavos[image needed] and 1 peso) issued by Angel Almada y Compañía with the text ‘We have received ... which we shall pay to the bearer’s order in this town in silver coin after charging an 8% discount and a 1% security fee’ (Recibimos ... que pagaremos á la órden del portador en moneda de plata con 8% descuento y 1% situación en esta plaza).

Angel Almada was of a new generation of businessmen in Alamos{footnote}Alamos was a colonial bastion, with a strong merchant class, hacendados with large land holdings, and old and distinguished families but it suffered from the decline in mining and by 1910 had actually lost population, to the unhappiness of its merchants. Many former residents left for Navojoa, Echojoa, and Huatabango, all thriving agricultural towns. The inhabitants blamed Alamos’ decline on Corral and his henchmen and eventually joined the ranks of the rebels.{/footnote}. He married Josefa Urrea, heiress to one of Alamos’ major families with interests in mining, agriculture and commerce. On 17 July 1887 he formed the firm, Angel Almada y Cía, with an initial capital of $10,418. Its personnel included Jesús A. Almada as limited partner (socio comanditario), Angel Almada as managing partner (socio administrador), and Ignacio E. Almada and Jesús G. Almada as employees{footnote}ANES, protocol notarial, 26 October 1889{/footnote}. The company was registered as a general merchant and operator of a warehouse and tobacco store in 1888{footnote}AAA, caja 1, exp.10{/footnote}. By 1893 it had increased its capital to $50,000 and Angel was the leading businessman in the region{footnote}AGHES, tomo 647{/footnote} and one of the richest merchants in the town{footnote}Angel Almada had massive savings (abultados ahorros) according to the Lista Nominal de los Vecinos Principales de Alamos 1892 (AGHES, carpeton 647){/footnote}.

advert for "La Favorita", 1895

Angel was involved in local politics from the 1870s until the turn of the century.

Mining enterprises, by their very nature, were often located in isolated mountainous areas with low population densities significantly distant from commercial centres. Mining entrepreneurs, therefore, had unique problems to contend with in organizing their enterprises. Their common problem was a lack of infrastructure—no streets, no churches, no schools, no residences, no utilities, and no banks or financial intermediaries. The specialised industries that might otherwise have provided these services were dissuaded from doing so by the high start-up costs and the enduring uncertainties of dealing with low-income communities that might be there today and gone tomorrow. Mining companies, therefore, built residences, churches, schools, and water works, and opened company stores or commissaries. In so doing, they became both buyers of labour from, and sellers of commodities to, the miners and their households. This kind of organization invited the use of scrip in lieu of ordinary money.

Scrip in the very beginning was little more than credit advanced against wages. Given the fact that most employees were earning merely enough to survive (or less) there would be little left at payday except the reckoning of accounts. If the company operated its own store (tienda de raya) the worker would draw goods against a personal account: this need not have involved anything more than book-keeping but sometimes more elaborate arrangements were used.

For instance, scrip coupon books ‘eliminated the tedious bookkeeping chores that were incident to over-the-counter credit (day book or journal entries followed by ledger entries)’. When a coupon book was issued to an employee ‘he signs for it on the form provided on the first leaf of the book, which the storekeeper tears out and retains for the company time-keeper, who deducts the amount from the man’s next time-check.’ Then, when the employee buys goods from the company store, ‘he pays in coupons, just as he would pay in cash, and the coupons are kept and counted the same as cash . . . . The coupon book is a medium of exchange between the company employees and the company store’{footnote}Richard H. Timberlake, Free Market Money in Coal-Mining Communities, in Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking, vol. 19, no. 4 (November 1987){/footnote}.

Such scrip could also be used, usually at a discount, at other local establishments (run in the main by Chinese immigrants{footnote}Within Sonora, a clear division developed between Mexican and European merchants on the one hand and Chinese retailers on the other. Established Sonoran retailers and agents, representing Mexican companies, (such as Seldner and Company, García and Bringas, and Anibal Mancini of Guaymas) opened stores and franchises at the mines. These major establishments catered to foreigners and Mexicans with economic resources, selling both luxury goods as well as basic necessities such as underwear, shirts, trousers, boots, sugar, and coffee. Unlike their Mexican counterparts, Chinese merchants usually sold inexpensive items, such as low-cost apparel, which miners could afford. More importantly, many Chinese also sold goods on credit, a practice frowned on by Europeans and other larger Mexican merchants. Stores such as those operated by Sam Lee at Minas Prietas and Fong Hong at La Colorada maintained copious credit records for their clients. On the wall of the store, small boxes with the names of the clients recorded a person’s debts. In this capacity the Chinese prospered and quickly established a monopoly over the lower spectrum of the consumer market.{/footnote}), provided these in turn had some arrangement for cashing in the scrip. As the company store did not sell alcohol – for the obvious reason that its sale would encourage absenteeism and worker inefficiency – workers also had to find ways to sell scrip for conventional currency in order to buy drink.

Besides overcoming the difficulty and danger of importing specie, another advantage of scrip was that the company could pay almost its entire payroll in scrip, disturbing only a few pesos of actual working capital, though it needed working capital for store goods.

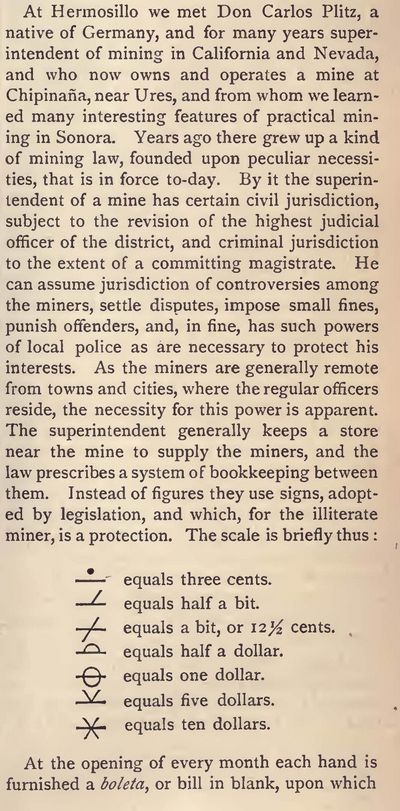

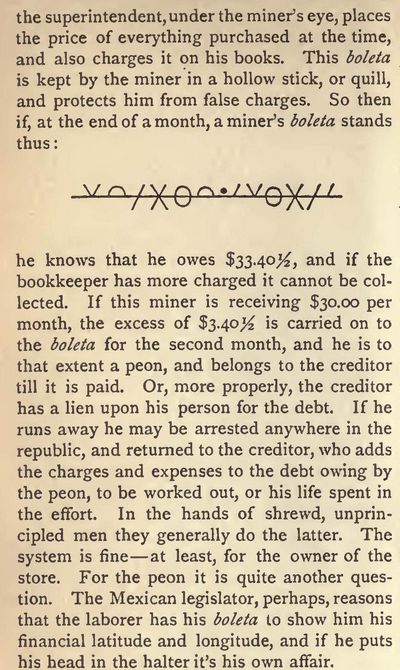

In 1898 the Guaymas newspaper El Correo de Sonora reported that the district judge has instituted an investigation into the practice of several local mining companies paying their workers in 'boletas' payable only at the company stores{footnote}The Two Republics, Mexico, 3 June 1898{/footnote}. A good descripton of boletas comes from Charles D. Poston's account of the Santa Rita Mining Company, in Tubac, Arizona, 80 kilometres north of Nogales, which, but for Manifest Destiny, would have been in Mexico. Believing debt peonage to be the norm, this company paid Mexicans twelve to fifteen dollars monthly versus thirty to seventy dollars a month plus board for Anglos, and it even lowered these costs by paying Mexicans with marked-up items from the company store. It paid Mexican workers with boletas, or coupons, which Poston claimed were used “among the merchants in the country and in Mexico.” Thirty-two percent of these Mexican “wages”, noted a colleague, returned to the company as profits at the company store. "Silver bars form rather an inconvenient currency, and necessity required some more convenient medium. We therefore adopted the Mexican system of "boletas". Engravings were made in New York, and paper money printed on pasteboard about two inches by three in small denominations, twelve and one half cents, twenty-five cents, fifty cents, one dollar, five dollars, ten dollars. Each boleta had a picture, by which the illiterate could ascertain its denomination, viz: twelve and a half cents, a pig; twenty-five cents, a calf; fifty cents, a rooster; one dollar, a horse; five dollars, a bull; ten dollars, a lion. With these "boletas" the hands were paid off every Saturday, and they were currency at the stores, and among the merchants of the country and in Mexico. When a run of silver was made, anyone holding tickets could have them redeemed in silver bars, or in exchange on San Francisco. This primitive system of greenbacks worked very well,—everybody holding boletas was interested in the success of the mines; and the whole community was dependent on the prosperity of the company. They were all redeemed"{footnote}Charles D. Poston, Building a State In Apache Land, 1894, pp 81-82{/footnote}.

Another system of boletas was described by James Wyatt Oates, in his "A Trip Into Sonora", published in The Californian magazine in 1880{footnote}The Californian, vol. II, August 1880. Compare also Grant Shepherd of Batopilas, explaining the phrase “He marked it down with a three-pronged fork” in his book The Silver Magnet: “There were many storekeepers who could neither read or write, nor had any ideas as to the usual figures employed by the initiated in that mysterious science known as arithmetic. I have known men who did thousands of dollars worth of business, profitable business, whose accounts were kept as follows:

A straight line was drawn across the page from left to right. You came in and purchased on credit one peso of goods … a circle was drawn half above and half below the line.

Maybe you then bought fifty cents worth of cigars for your friends who had just come in or maybe it was some other things worth fifty cents, cuatro reales. Or four bits, take your choice. Your account then had a half circle above the line.

If you bought twenty-five cents worth of anything, you had two lines vertically drawn from above down through the line.

If one real worth of salt, for instance, it was one such line.

If a medio real – six and a quarter cents – it was a short line just above the horizontal line.

If three and an eight cents, a short line just below the horizontal line.

Now, if instead of using an ordinary pencil or pen with an orthodox one-point you used a three-pronged fork the result would not be the same, and it would rather favor the keeper of the account and not the purchaser.” {/footnote}.

|

|

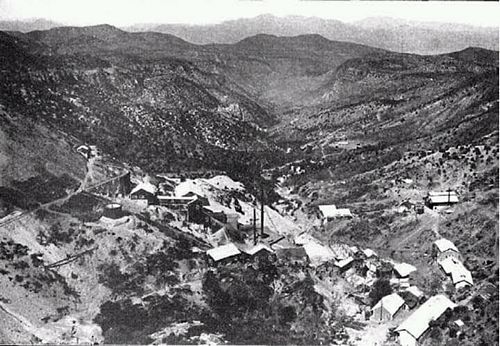

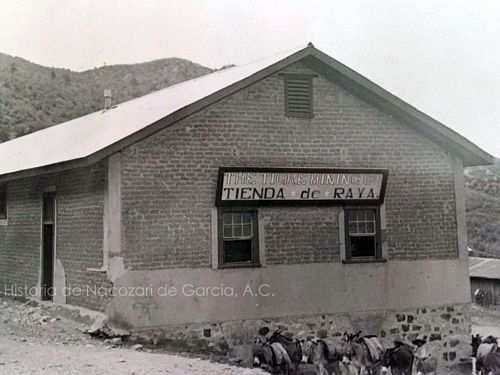

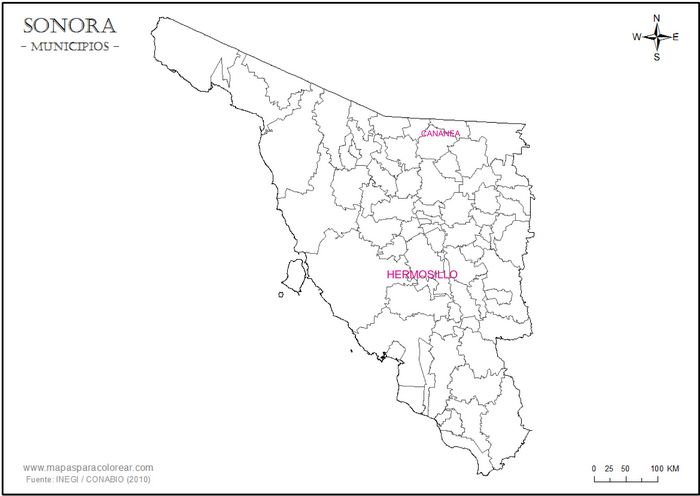

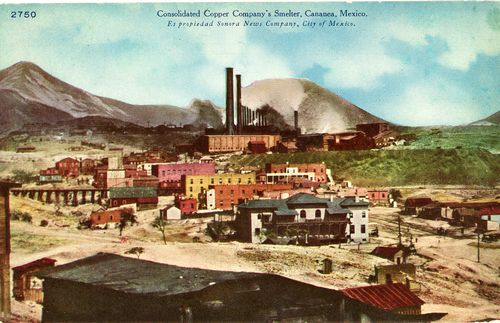

At the end of the nineteenth century there was a surge of foreign investment in mining in northern Sonora, with some foreign corporations establishing company towns. The largest were those of the Cananea Consolidated Copper Company, the Moctezuma Copper Company, El Tigre Mining Company and the Creston Mining Company. The owners controlled everything in these towns: food, housing, schools (where available), the police, and local government.

The tiendas mixtas of the mining companies had a far greater turnover than the average shopkeepers in the area and competition from local independent merchants was discouraged because it endangered the profits of company stores. The tienda of the Cananea Consolidated Copper Company in Cananea had annual sales of 145,000 pesos, compared with 12,000 and 20,000 respectively of its nearest competitor, the grocery store of Hofman y Claud. The tiendas of the Moctezuma Copper Company in Placeritos and Pilares, both in Nacozari, had combined sales of 30,000 pesos per year compared with the 8,000 pesos of Juan Manuel, their nearest competitor in the municipio: whilst the tienda of The Lucky Tiger Mining Company in the mining town of El Tigre sold 25,000 pesos compared to the 2,100 pesos of its nearest rival, Francisco H. Langston.

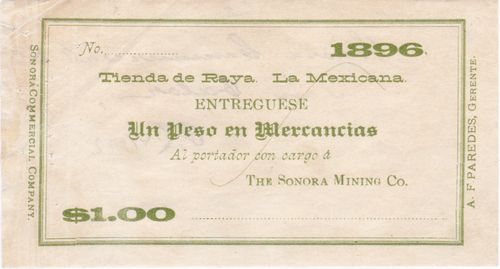

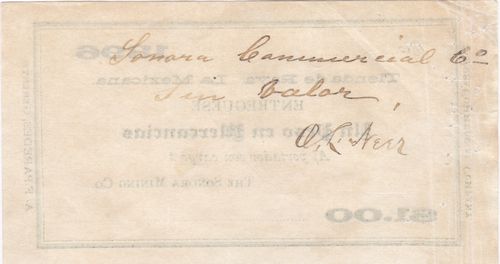

This note, dated 1896, authorised the company store of La Mina Mexicana to give the bearer one peso’s worth of merchandise and to debit the account of the Sonora Mining Company. The legend at the edges refer to A. F. Paredes, as manager and the Sonora Commercial Company. It is unclear whether Paredes is manager of the Sonora Mining Company, the Sonora Commercial Company, or both.

The note is an unnumbered and unsigned example. On the reverse it has the annotation “Sonora Commercial Co. Sin valor” and the signature of [ ][identification needed].

La Mina Mexicana was seventy-five miles from Nogales. In a write up in 1897 The Mexican Herald reported that the mine was owned by A. F. Paredes & Co. and was “one of the best silver and lead mines in the state. L. L. Lindsey (sic) is the superintendent and he has a model camp. Everyone does his work and the camp is neat and clean. There is no drunkenness allowed. There is a system of checks and only three drinks a day are allowed each man. More than that amount is liable to lead the drinker to intemperance and then he will lose his job, for when a man gets drunk he is discharged. The result is that there is no more orderly camp in the whole state of Sonora. The company store is well stocked with general merchandise and prices are very reasonable. … The ore is hauled to Nogales where it is loaded onto cars and shipped to El Paso, Texas, for treatment. There are one hundred men employed all the time taking out ore and doing development work{footnote}The Mexican Herald, 16 June 1897{/footnote}.

A. F. Paredes appears to have a series of different employments, including storekeeper and mine-owner. By 1878 he was running J. Giundani & Co.’s wholesale and retail general store in Florence, Arizona{footnote}The Arizona Citizen, 5 April 1878{/footnote} and was still working for them at Fairbank in 1890{footnote}Tombstone Daily Prospector, 16 October 1890{/footnote}. By 1895 he was manager of La Mina Mexicana{footnote}The Oasis, 12 October 1895{/footnote}. In 1897, A. F. Paredes & Co. operated the "La Internacional" general store on Morley Avenue, Nogales, Arizona{footnote}The Oasis, 27 February 1897{/footnote}. Paredes resumed management of the mine on 1 June 1898{footnote}The Mexican Herald, 25 July 1898{/footnote} and was still there in March 1900{footnote}The Oasis, Vol. XIV, No. 17, 24 March 1900{/footnote}. In early 1899 Paredes establish a stage coach between Nogales and Cananea{footnote} Arizona Republican, 31 March 1899; The Oasis, 13 May 1899{/footnote}. In 1912 he became the editor, manager and director of La Voz de Cananea, a biweekly newspaper, and, as such, was shot in August 1914, with two other journalists, by Los Chiquitos, the nickname given to Carranza's supporters by Maytorena's group.

In March 1898 the Sonora Commercial Company, owned by Proto Brothers{footnote} Antonio Proto was born of Greek parentage in Beria, Macedonia (modern-day Veria) in 1844 and came to the United States in 1873. He became a naturalized citizen on 19 August 1875 in San Francisco. Louis was also born in Beria on 24 December 1854.

In 1879 the Protoses were living in San Francisco where they owned a restaurant. In 1882, they moved to Tucson which was then a part of the Arizona Territory. After a short stay in Tucson, the ever-enterprising Proto Brothers purchased businesses in Tombstone and Sonora, Mexico engaging in general merchandise. In 1884 they moved to Nogales, Arizona opening a bakery on Morley Avenue and turning it into a general merchandise store. The brothers were aided in their growing business by three of their nephews Spiro, Anton, and Manuel.

Aside from their mercantile businesses on both sides of the border the Proto brother’s interests soon included cattle, horses, timber sales, mining, oil exploration and other ventures.

The Proto brothers married into local Mexican families who had long held vast ranches in the region. Tensions between these families led to the assassination of Louis Proto in early 1909. While the five assassins were eventually caught and the principal murderer shot by firing squad, the tensions along the U.S./Mexico border were such at this specific moment in time that Proto’s death almost led to war. Certainly, part of the jealousy and hate directed toward the Proto family was based in part on the fact that the brothers always took an active interest in public affairs. In terms of the Arizona side of the border, Anton Proto was president of the Nogales Protective Association, spent four terms on the city council and in 1894 was elected mayor of Nogales, serving one term.

In May 1914 the family established the Arizona Gas and Electric Company which served both sides of the border (Border Vidette, 2 May 1914).

Self-made millionaires, these two brothers and their extended family literally helped to build both the Arizona city of Nogales and enriched territories and businesses in nearby Mexico.{/footnote}, completed building a new store on Arizpe Street, Nogales, Sonora, to house a large and varied stock of groceries and mine supplies{footnote}The Oasis, 12 March 1898{/footnote} with Spiro Proto as manager{footnote}The Oasis, 13 March 1898{/footnote}. In September 1900 it was reported that the Sonora Commercial Co. had now passed to the management of Luis Proto, of the firm of Proto Bros. as Manuel Mascareñas, Jr., had retired from the management of the firm{footnote}The Mexican Herald, 30 September 1900{/footnote}.

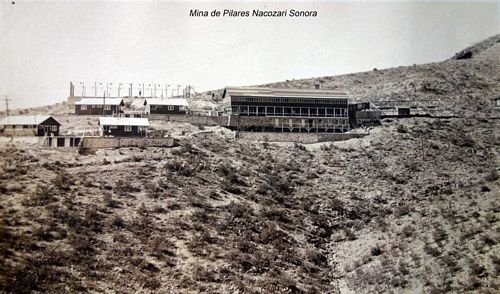

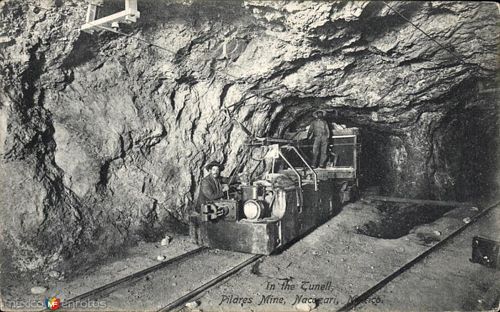

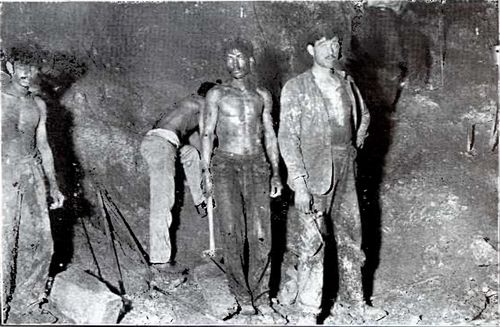

The mines at Pilares de Nacozari, six miles from Nacozari, were established around 1867 by U. B. Treaner as the Moctezuma Concentrating Company. The mines passed to the Guggenheims, and in 1896, as the Moctezuma Copper Company, were acquired by the American Phelps, Dodge and Co.

Because of their Quaker convictions Phelps, Dodge built a model town at Pilares: instead of adobe huts, the miners lived in one-room cottages fifteen-foot square and the company supplied clubrooms, libraries, billiards parlours, dance halls and shower baths. In Nacozari, the company had a smelting plant and a generating plant, operated the railway to Agua Prieta and Douglas and provided stores, a public library, hospital and school. By 1910 the company controlled a town of 4,000 inhabitants: it paid the salaries of the comisario, the schoolmasters and the police.

The Moctezuma Copper Company paid with boletas to be used only in the company store. One such boleta was of yellow cardboard. On the face it read

Valor de diez centavos en mercancías.

10 cts.

Moctezuma Copper Company.

Nacozari, Mexico.

No es negociable.

with a signature, and the reverse carried a 1c revenue stamp, cancelled with the company seal[image needed].

In July 1904 El Diario del Hogar published a letter from Placeritos de Nacozari complaining that the company paid its workers with scrip called ‘boletos’. The pay month ran from the first to the first but the company only paid on the tenth with cheques drawn on the Banco de Sonora. These were not cashed unless the worker spent at least ten per cent and then they would receive even smaller cheques so that someone who wanted to change forty pesos had to spend at least twenty-five pesos in the store. The trade was completely monopolized: there was a single butcher's shop, owned by the company, with all the good pieces of meat given to the Chinese of the company-owned hotel or to the Americans, senior employees of the company. The Mexicans had to resign themselves to take the meat they were given, at an exorbitant price, or not to eat. Other commodities were similarly overpriced. The authorities only permitted the company to trade, and even if they did, merchants would not gain because they would have to sell their goods for boletos, and use them to buy wholesale from the same company which charged a commission of 20 percent{footnote}El Diario del Hogar, 29 July 1904{/footnote}. A few months later Regeneración again reported that at the end of the month the company paid any outstanding salary with a cheque drawn on a distant bank. It was willing to encash these cheques on condition that 10% of the value was spent on merchandise in the company store, but the worker then just received another cheque for a smaller amount{footnote}Regeneración, 11 March 1905{/footnote}.

There was a Banco de Moctezuma in Moctezuma, 80 kilometres south of Nacozari, with the Compañía Mercantil, bank and hotel all housed in the same brick building on the main square{footnote}Mr. Hunter was the manager (Manuel Guerrero, Album Descriptivo del Distrito de Moctezuma, Cumpas 1909){/footnote}. The Moctezuma Banking Company, S.A. went into liquidation on 25 July 1910{footnote}La Constitución, 15 June 1910. B. A. Packard was President{/footnote}.

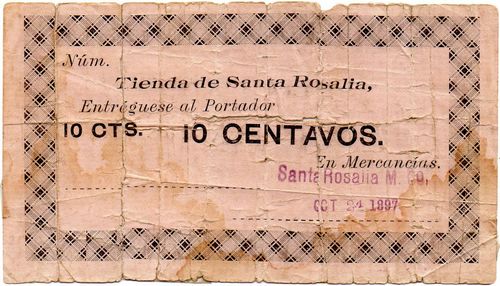

The rich gold mine of Santa Rosalía, fifteen miles west of Arizpe, was worked by the early Spaniards but abandoned when the water levels were reached. In 1880 George F. Beveridge, the Superintendent of the El Gascher mine in Sonora, located the abandoned mine, but for ten or twelve years he could do nothing with it and held it merely by relocation. Finally in December 1894, Beveridge gave a deed of the property to a company organized by a group of San Francisco businessmen, with Beveridge to take his pay for the mine in stock{footnote}Sacramento Daily Union, Volume 95, Number 26, 19 March 1898{/footnote}. Beveridge and Augustus A. Abbott took personal charge with Antonio Acuña, of Arizpe, as foreman. At first, results were not very satisfactory but one day Acuña found at one place, against the side of an arroyo. a lot of rubbish which he cleared away, uncovering the entrance to an old tunnel, closed with a heavy wooden door and locked. The door was soon opened and the tunnel traversed a distance of 300 feet, when another door was encountered. Passing that they entered the old Spanish workings. There they found a two foot streak of ore so rich that the first carload shipped netted $22,000 in gold, and the first three carloads averaged more than $20,000 each{footnote}The Oasis, Nogales, 3 August 1901{/footnote}.

| from | to | total number |

total value |

|

| 5c | ||||

| 10c |

We know of two notes, for 5c and 10c in goods (En Mercancias), produced by the company store (Tienda de Santa Rosalia). The former is signed by L. Lindsay and the latter datestamped “Santa Rosalia M. Co. OCT 24 1897.

|

At the Santa Rosalia mine, he reportedly located and opened one of the richest veins of copper in the world. He went on to become the multi-millionaire owner of large cattle and stock ranches in Sonora and of other mining and ranching properties in Arizona, Nevada and California. Around 1905 he centralized his business enterprises in Los Angeles, energetically expanding his efforts to include large stakeholdings and directorships in banks, oceanfront real estate development, and in building materials, including a firm that produced the miles of sewer pipe new Angelenos would require and the Western Art Tile Works. The self- proclaimed "Talc King", in 1912 he developed the Western mine in San Bernadino, to extract the mineral to use in these two large pottery businesses. He vigorously expanded the mine and by the end of 1920 had taken out roughly $500,000 in talc. The mine boomed, but Lindsay had expanded too quickly and overextended his credit, and in 1921 the business went belly up, even though talc shipments continued under a new owner. For many years during his residence in Los Angeles Lindsay was a director of the Los Angeles Trust Company and at one time was president of the First National Bank of Nogales, Arizona. He was responsible for “one of the most delicate yet robustly designed houses ever seen in Los Angeles” at 3234 West Adams Boulevard. The design “recalls the shapes of Sullivan and Wright” while also unusual is the fact that the house is built entirely of hard burned terra cotta tile, laid up in cement mortar, and reinforced every two or three tiers of tiles with a webbing of steel wire mesh, making it virtually earthquake proof. Lindsay died in Los Angeles on 11 September 1931. |

|

In this same year, under the heading “La burguesia en México (the bourgeoisie in Mexico)” a newspaper correspondent wrote about the mine at Bacochi, Santa Rosalía, “With the tienda de raya, there are six shops of importance in the town and also twenty-six or twenty-seven cantinas, all more and less on a regular scale. The only thing to regret, according to well-informed people, is that the daily wage of the workers (whose number exceeds 200) does not exceed $1.50. Likewise, the inhabitants, should complain about the despotism of the company’s employees. … On the door of the tienda there is a sign that says, more or less: "The admittance of any person without business to this establishment is prohibited, and any such person will be fined two pesos.” What authorization do those gentlemen, who are nothing more than French and nothing else, have to impose fines?"{footnote}La Patria, 9 June 1897{/footnote}.

In Cumpas, midway between Nacozari and Moctezuma, El Tigre Mining Company gained its concession in exchange for maintaining a school and paying for the police.

El Tajo Mining company operated the San Gerónimo mine, located 18 miles east of Poza, a station on the Sonora railroad, in the district of Ures. In July 1912 the Comisario de Policía at San Gerónimo reported to the state government that the company was breaking the law by issuing vales or ‘tikets’ in its tienda de raya{footnote}El Estado de Sonora, 6 August 1912{/footnote}. However a report of 31 July stated that the company was paying with cheques, which people had difficulty changing, because of a lack of coinage{footnote}AGHES, Fondo Oficialidad Mayor, tomo 2913{/footnote}.

La Trinidad (in a snowstorm)

The La Trinidad mines at Sahuaripa, 165 kilometres east of Hermosillo, had been owned and operated by the Matias Alzua family for many years, but in 1884 were sold to James Thomas Browne of England. Browne sold the property on to La Trinidad Limited of London for a handsome profit{footnote}AGHES, tomo [ ], caja 547: La Constitución, 5 October 1883{/footnote}. La Trinidad Limited, incorporated in 1884, issued 100,000 shares of stock at five pounds each.

The new owners of the La Trinidad mines immediately encountered several problems which hampered their operations and also suffered from poor working relations with the miners and the local townspeople, especially the merchants{footnote}This section is based on "Sonora in the Age of Ramon Corral, 1875-1990", by Delmar Leon Been, a dissertation submitted to the University of Arizona, 1972{/footnote}. Discontent erupted into a strike in February 1888. The labourers demanded more pay, claiming that one peso a day for work outside of the mines and one and a half pesos for work inside was too low. On the grounds that the miners were receiving the highest pay in any mining area, the company authorities refused to meet the demands, and attempted to break the strike by bringing in Yaqui miners plus other workers from outside the district. Although the strikers refrained from any violent actions, they cursed the strikebreakers who arrived on 15 February and hindered the operations of the company{footnote}AGHES, tomo 185, caja 606 letter District Prefect Loreto Trujillo to Governor Ramon Corral, 17 February 1888{/footnote}. Because the mine could operate at only partial capacity, the General Manager, Edmund Harvey, requested help from the Presidente Municipal, Antonio Encinas{footnote} distinguish between Antonio Encinas and senior alderman (Primer Regidor) Manuel Pablos Encinas, who encouraged the workers{/footnote}. Encinas relayed the message to the Prefect of the district, Loreto Trujillo, who rode all night from Sahuaripa to arrive at La Trinidad on 16 February. Trujillo immediately posted a guard of twentyfive men to protect the mining properties and personally informed the general manager that his operations would not be harmed. After conferring with Harvey and Encinas, Trujillo arrested three of the leaders of the strike{footnote}AGHES, tomo 185, caja 606 letter Trujillo to Corral, 17 February 1888: letter Trujillo to Corral, 25 February 1888{/footnote}, and the following month they were sentenced to two months imprisonment for crimes against industry and commerce{footnote}Ramón Corral, Memoria de la Administración Pública del Estado, Hermosillo, 1891{/footnote}.

Before returning to Sahuaripa, Trujillo left orders for Encinas to notify him if any further disturbance occurred. Moreover, he had Encinas post a decree stating that any citizen who lacked an income should present himself for work under penalty of vagrancy. Included in the decree also was a declaration that any person or persons who attempted to employ the use of violence, physical or moral, for the purpose of increasing or lowering the wages of workers, or to impede the free exercise of industry, would be immediately apprehended{footnote}AGHES, tomo 185, caja 606 Manifesto 19 February 1888{/footnote}. Trujillo returned to Sahuaripa where he drafted a detailed report of the incident for the secretary of state. Governor Corral ordered Trujillo to continue to protect the mining operations and the official state newspaper, La Constitución, printed one short statement condemning the strike, and agreed with Edmund Harvey that La Trinidad Limited paid the highest wages in any mining district{footnote}La Constitución, 24 February 1888{/footnote}.

However, discontent continued and threatened to erupt into a violent clash between the workers and company officials. In addition to the complaint of low wages, the miners claimed that the company's established policy of payment in script[image needed], which could then be redeemed at local stores for goods, cheated them of their earnings. The company did not intentionally cheat the miners, but, unfortunately for the labourers, the English firm did not enjoy good relations with the local merchants, and only about half of them would accept the script. Those merchants who did accept the company's script discounted it as much as one-third of its value. Instead of seeking redress from the merchants, the miners blamed the company and demanded that they be paid silver each week{footnote}AGHES, tomo 185, caja 606 letter Trujillo to Corral, 22 February 1889{/footnote}. After the strike Harvey promised that he would reform the method of pay for the miners, but he delayed doing so for several months while tension mounted steadily among the workers. Finally, in a desperate attempt to alleviate the pressure which hampered the operations of the company, Harvey agreed to pay the workers each week, and he also established a company store where the labourers could purchase goods at cost price. Harvey's actions satisfied only one of the grievances and the majority of workers still demanded an increase in pay and now the local merchants became even more hostile because they resented the competition from the company store. The discontent affected the operations of the mines and production decreased considerably{footnote}ibid.{/footnote}.

Instead of requesting help from either the district or the state level or even from the British ambassador in Mexico City, Harvey bombarded the London office with complaints. Steward Pixley, the Chairman of Board of La Trinidad Limited, requested help from the English Minister of Foreign Affairs, Lord Salisbury. Salisbury's office contacted the English Ambassador to Mexico, Sir Spenser St. John, who informed the Mexican Minister of Foreign Affairs, Ignacio Mariscal, who in turn called upon the Secretario de Fomento, Manuel Fernández, who notified President Díaz about the problem confronting La Trinidad Limited. Díaz ordered that he wanted the labour disturbances to end{footnote}AGHES, tomo 185, caja 606, Manuel Fernández, Secretario de Fomento, to Corral, 12 January 1889{/footnote}. At the same time that Corral replied that he was aware of only one strike against the company and that one had been settled to the satisfaction of the company, he also ordered Trujillo to check into the matter{footnote} AGHES, tomo 185, caja 606{/footnote}. Trujillo, in turn, sent an inquiry to the local Presidente Municipal. About the time that Encinas replied with his report on conditions at La Trinidad, Harvey made his first report of the situation to the district prefect. Encinas informed Trujillo about the changes which the company had made in October and November concerning the pay of the workers and the company store which had been established for the miners and assured the prefect that the local authorities had and would protect the mining operation. According to Encinas, "the workers are much happier and only a small percent remain discontented but these are among the most ignorant and insignificant element{footnote}AGHES, tomo 185, caja 606 Encinas to Trujillo, 13 February 1889{/footnote}”. Contrary to the picture of tranquility which Encinas described, Harvey complained of a lack of guarantees by the Presidente Municipal and alleged that his company was the target of discontent within the community. Moreover, he complained that some of the leaders of the 1888 strike had returned to the area and were agitating those who worked in the mines{footnote}AGHES, tomo 185, caja 606 Trujillo to Corral, 22 February 1889{/footnote}.

On the basis of Encinas’ letter, Trujillo dismissed the complaints by Harvey and in his report to Corral, the district prefect wrote that Harvey and his attorney "yell strike at what has occurred since time immemorial in this mining area: that is, workers arrive for a week or more of work and when they have earned enough for their needs they return home for a number of days. Mr. Harvey calls this a strike{footnote}ibid.{/footnote}”. Trujillo accompanied his letter with that of Encinas which reported that no major difficulty existed at La Trinidad. Corral seemed satisfied with the general report. He agreed with the district prefect that Harvey's complaints were too vague and too general to stand up in court. "It is important," Corral wrote, "that Mr. Harvey knows that if Manuel Pablos Encinas or another person is promoting disturbances that concrete evidence must be obtained in order to prosecute. These acts must be proved before the law{footnote}AGHES, tomo 185, caja 606 Corral to Trujillo, 1 March 1889{/footnote}”

The comments by Trujillo indicated one of the major sources of irritation between the company officials and the miners. Used to a more dependable work force, Harvey and his staff could not, or would not, understand the Mexican attitude toward work. Most of the mining operations were in the mountainous regions away from settled communities. Frequently the miner would leave his family behind, but only until he had earned enough to sustain himself at which time he would return home to visit for several days. The Yaqui as well as the Mexican miners followed this custom, and consequently, the mining superintendent of the mines had difficulty in operating at full production capacity{footnote}AGHES, tomo 185, caja 606 Trujillo to Corral, 22 February 1889{/footnote}. Thus contrary to the report of Encinas, a clash between the miners and the company officials was imminent.

On 24 February 1889, just two days after Trujillo notified Corral that all was well at La Trinidad, a group of miners attacked several of the officials of the mining company. According to the company superintendent, Richard R. Hawkins, about eight o'clock at night while the mine superintendent, Mr. J. Fredenrick, sat on the front porch of his home talking with four or five other employees, a gang of half drunken natives appeared and began to insult the men in the grossest manner, calling them "gringos cabrones." When Fredenrick requested that they leave, the miners bombarded the house with rocks and drove the group inside. The superintendent and his friends barricaded the doors and "patiently awaiting succor stood the little band of pale determined men firmly grasping their revolvers determined to sell their lives dearly — They could have shot down scores and their self restraint is simply marvelous when you consider the ordeal through which they were passing"{footnote}AGHES, tomo 185, caja 606, Hawkins to Consul Alexander Willard, 25 February 1889{/footnote}. The noise attracted Hawkins and, with the cooperation of the local authorities, he organized a force to suppress the outbreak.

After this violent outburst, Harvey contacted Corral requesting that he induct the troublemakers into the military{footnote}AGHES, tomo 185, caja 606 Harvey to Corral, 26 February 1889{/footnote}. Corral replied that he could not grant this request but did apologize for the attack, stating that "it causes me much pain to see your business attacked and you can be assured that I shall see with the greatest interest that peace and guarantees are enjoyed by your company. I ordered Prefect Trujillo to see to it that those who attacked Fredenrick and his friends are punished with all the vigour of our laws{footnote}AGHES, tomo 185, caja 606 Corral to Trujillo, 7 March 1889{/footnote}". At the same time Corral sent a stinging rebuke to Trujillo instructing him to protect the mining company as he previously had been ordered. "I now repeat those orders to you and that those guilty be punished with all the vigour of the law”. Corral added that the prefect was to make sure the local judge understood the situation, and received the proper instructions concerning the sentence {footnote}ibid.{/footnote}.

Harvey wrote again to Corral explaining that the miners who continued to work for him could not enter town without being harassed by rock throwers, and that Encinas had done nothing to prevent the attacks. He further complained about the erratic work habits of the miners, which caused the company to run at half capacity{footnote}AGHES, tomo 185, caja 606 Harvey to Corral, 16 March 1889{/footnote}. Even if Corral had demonstrated his willingness to protect the mine’s property, he realized the futility in trying to alter work habits which had developed over many decades. So he replied that he knew of no law which obliged a man to work for a determined number of days a week. In regard to Encinas, Corral suggested that the general manager use his influence in the municipal elections scheduled in August{footnote}AGHES, tomo 185, caja 606 Corral to Harvey,26 March 1889{/footnote}.

The company's total lack of knowledge of local customs became even more apparent when Harvey returned to England in late April 1889 {footnote}One of Harvey's letters to the home office in London clearly demonstrated his inability to make judgments. According to the Englishman, "the present Governor has no love for foreigners (Gringos as we are called.). If a Mexican wants anything even if it is out of the common, he gets it at once but we get nothing . . . (FO, F. 0. 50, vol. 472, Edmund Harvey to Stewart Pixley,1 October 1888, quoted in Stewart Pixley to Sir T. V. Lister,26 February 1889). However, in reality Corral worked to attract foreign companies to Sonora and always cautioned the local authorities "to give all kinds of guarantees to the mining companies." (AGHES, tomo [ ], caja 651 Corral to the mayor of Minas Prietas, 12 December 1892: tomo 185, caja 606, Corral to Trujillo, 7 March 1889). The company’s attitude is also demonstrated by the superintendent, Richard R, Hawkins, who could write “The La Trinidad Limitada have always treated their native employees in an exceptionally kind and liberal manner. Not only do we pay higher wages than elsewhere in Mexico but we have opened a general store where all of our workmen can purchase supplies of every description at the cost price to us, an excess of liberality unparalleled in Mexican mining history. Our treatment of the men has been really patriarchal, and this outbreak is consequently inexcusable (AGHES, tomo 185, caja 606, letter to US consul, Guaymas 25 February 1889 my italics){/footnote}. The general manager reported that the problems which confronted the mining company in Sonora stemmed from the local authorities not carrying out the orders of the district prefect. Pixley, the chairman of the board, forwarded Harvey's comment to Lord Salisbury and requested that the minister of foreign affairs use his influence with the Mexican government to obtain a favourable appointment to the position of Municipal President at La Trinidad{footnote}FO, F. 0. 50, vol. 472 Stewart Pixley to Foreign Office, 29 April 1889{/footnote}. Ambassador St. John, who answered Pixley, informed the chairman that municipal positions were arranged at the state level and not the national level and the ambassador suggested that the company give pecuniary assistance to the local authorities to prevent further difficulties. "Mexican officials are so poorly paid, that they will always aid a foreign company that has no objection to making their position more endurable{footnote}FO, F.0. 50, vol. 468 Spencer St. John to Sir T. H. Sanderson, 4 May 1889{/footnote}".

In spite of Corral's efforts to alleviate the problems of La Trinidad Limited, the mining operations folded in 1893 and the property reverted to the Alsua family{footnote}SD papers, J. Alexander Forbes to secretary of state. May I, 1893, "Consular Despatches, Guaymas," roll 9{/footnote}.

For tokens issued by the Trinidad store, see here.

Minas Prietas (now La Colorada) is situated 45 kilometres south east of Hermosillo. Gold was first discovered by Jesuit missionaries in the district in 1740, and mining began shortly thereafter. Mining continued until about 1745 but was terminated as a result of Yaqui Indian attacks. Spanish miners resumed work on the mines in 1790 and continued until they reached the water table at a depth between 30 and 60 metres. In 1860, an English company installed pumps and built a 48 stamp mill. In 1865, Mr Ricardo Johnson, with the financial backing of the wealthy Ortiz merchants of Hermosillo, obtained the El Creston, Minas Prietas and La Colorada Mines, and in the same year, Mr Pedro Monteverde located the Amarillas Mine and Mr. Juan Vasquez located the Gran Central.

For several years Johnson worked the site, but his presence did not lead to any formal settlement in the area. Like many Sonoran elites of the time{footnote}Other Sonoran notables, including Ramón Corral, Ignacio Bonillas, Pedro Negro, and Pedro Pinelli, also joined the early rush to claim mines at Minas Prietas ("History of Amarillas" The Oasis, 30 December 1899). Corral did not mind using public office to enrich himself and his close associates. In 1896 this group sold their interest to the Gran Central and made a handsome profit. The company retained the services of the governor as their consul and paid him $250 a month until 1906. (Biblioteca CRN-INAH, Libro de contabilidad “Crestón Colorado Co.”, Sep-Nov 1905){/footnote}, Johnson and his benefactors did not have any long-term interest in actually exploiting the mine but rather hoped to profit by selling it to foreign investors. In 1877 Johnson sold his holdings to a group of bankers from Cleveland, Ohio, who organized the Creston-Colorado Company. Johnson then built a 10 stamp mill on the Minas Prietas property. The property was subsequently sold to the Pan American Company of New York in 1888, who installed one of the first operating cyanidation plants. In 1895, the London Exploration Company purchased the Gran Central, Amarillas and La Verde Mines and constructed a 150 ton cyanide mill to treat ore and previously mined amalgamated tailings. The Mines Company of America acquired the Creston, Minas Prietas and La Colorada mines in 1902 and built a 400 ton cyanide mill. In 1913 they purchased the Gran Central, Amarillas and La Verde mines and built a 300 ton cyanide plant at Amarillas.

Besides these large-scale operations, the areas around the mines also included over one hundred separate mining claims operated by Mexicans and foreigners. Firms like the Pan American Mining Company operated smaller diggings in nearby hills{footnote}"Pan American Mining Company," The Oasis, 31 August 1895{/footnote}, while others bought and reprocessed tailings from the Crestón Colorada. This arrangement allowed smaller, less capitalised enterprises to profit.

At the Creston Colorada workers received a combination of wages and coupons (boletas)[image needed] which they redeemed for products at the two company-operated tiendas de raya, the Prietas Store and the Gran Central Stores. Despite charging inflated prices for most basic items, the availability of credit continued to attract many workers. To circumvent the tienda de raya, many labourers began falsifying the boletas{footnote}AMLC, Presidencía, caja 1, Justicia, 1898-1904, March, 1897. Antonio Madrid arrested for false boletas{/footnote}: a lucrative black market in counterfeit boletas plagued the Gran Central Store{footnote}The Oasis, November 13, 1897{/footnote} and it abandoned the system after 1897 and paid its workers in cash.

In May 1900 a newspaper reported that the tienda de raya in Minas Prietas bought in the chits (fichas) with which workers were paid at a 25% discount{footnote}El Amigo de la Verdad, Puebla, 5 May 1900{/footnote} whilst another newspaper stated that they had replaced the fichas with boletos{footnote} “The Mexican government has notified the company store at La Colorada that the issue of "fichas," or tokens exchangeable for goods, is an act of government the same as coining money, and prohibited the practice. As a result the workmen who go to the store with their pay "boletos" take the goods directly, without using the "fichas," the rule being to punch from the "boleto" not less than one dollar in value and supplying goods to that amount. Under the old system the "fichas" were given when the “boleto” was presented, and the workman took the goods when he wanted them, exchanging the "fichas" therefor.” (The Oasis, Nogales, 9 June 1900){/footnote}.

The Creston Colorada resorted to issuing notes in 1915 because of the Revolution.

In 1912 the miners at La Dura went on strike because of the exhorbitant prices at the tienda de raya and the fact that they were paid monthly. They returned to work when the company agreed to fortnightly payments and to reduce the prices in the tienda de raya{footnote}La Gaceta de Guadalajara, 7 April 1912. The newspaper article places La Dura in Cananea, but it is in fact in Rosario{/footnote}.

On circumstantial evidence La Quintera Mining Company Limited is one of the best candidates for issuing paper. This mine was situated at La Aduana, just west of Alamos. It was discovered in colonial days and operated under various owners until 1909 when work on a large scale was suspended.

In 1898 Brigido Caro, editor of El Sonorense, a newspaper published in Alamos, revealed that the mining company was monopolising the public water supply at La Aduana, denuding the hills of wood and timber and illegally paying its workers with scrip (cacharpas). Caro’s articles aroused people to demand that the abuses be corrected and with the aid of the state governor the mining company was forced to reform and pay a large indemnity to the city{footnote}Rachel French, Alamos Sonora’s Silver City, in The Smoke Signal, Spring 1962, Tucson{/footnote}.

It is known that the company issued metal tokens, manufactured by L. H. Moise of San Francisco, and appears to have also reused old stocks of tokens from Ocharan y Cia. of Palmarejo, Chihuahua{footnote}Elwin C. Leslie, The Palmarejo Railroad Token, in Plus Ultra, 69, [ ]{/footnote} but it may also have used paper. Both the mining company in nearby Palmarejo, which did issue paper, and this Alamos company were British owned and both shared, as agent in Guaymas, Luis A. Martínez.

In his youth Ignacio Lorenzo Almada ran the accounts for La Quintera. Ignacio Lorenzo established a casa comercial in Alamos in 1893 and was the Alamos agent of the Banco Minero de Chihuahua{footnote}J. R. Southworth, El Estado de Sonora. Sus Industrias, Comerciales, Mineras y Manufactureras, Nogales, Arizona, 1897{/footnote}, whilst another member of the family, Jesus G. Almada, signed the notes used in the tienda de raya in Palmarejo, Chihuahua.

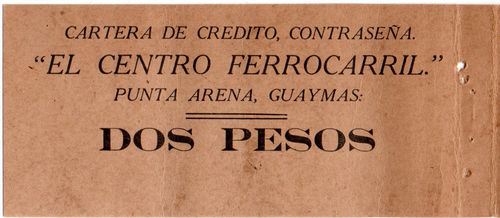

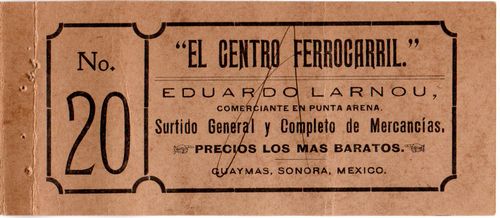

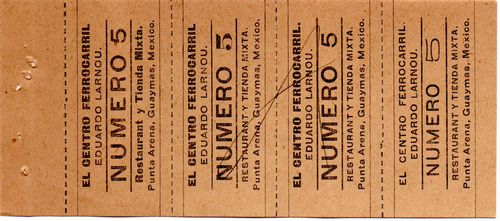

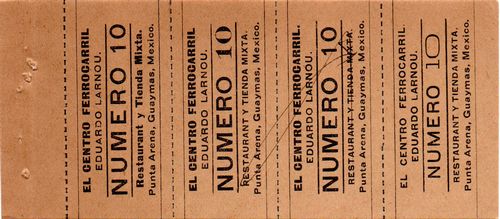

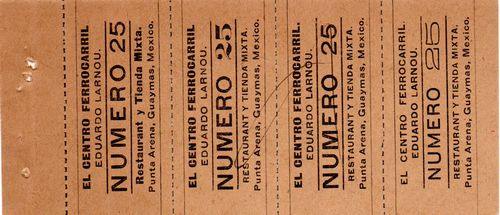

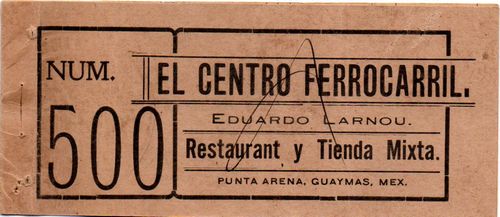

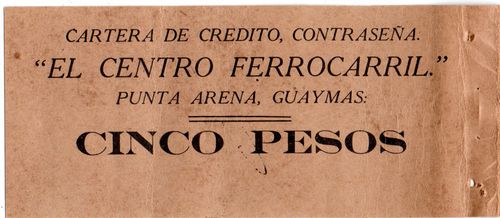

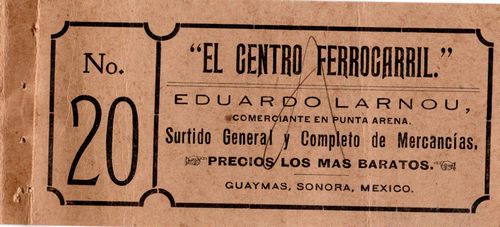

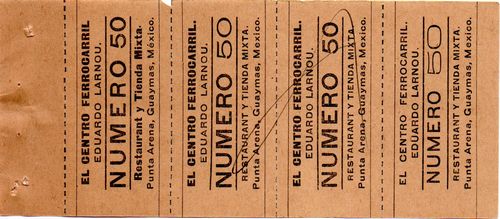

The “Centro Ferrocarril” was a general store or restaurant and store run by Eduardo Larnou, a French businessman, in Puenta Arena, a barrio of Guaymas that housed various businesses including the railway’s Round House. The railway later moved its operations to Empalme.

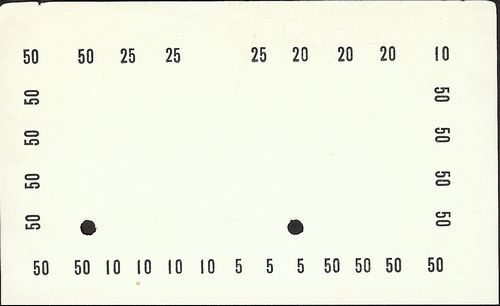

We know of two different types of booklets containing coupons, one for a total value of $2 and the other for $5, though the values of the coupons were designated as números: 5, 10, 25 or 50.

front cover of $2 booklet

inside front cover of $2 booklet

inside back cover of $2 booklet

front cover of $5 booklet

inside front cover of $5 booklet

inside back cover of $5 booklet

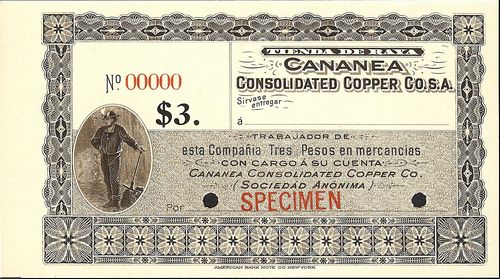

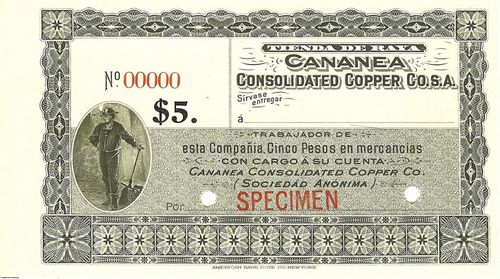

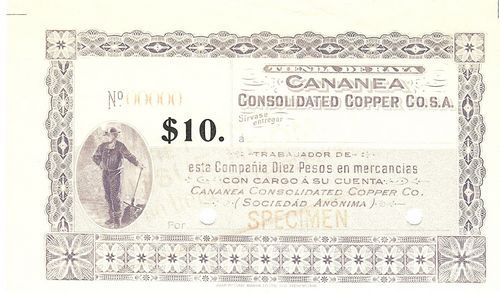

The large American-owned mine at Cananea was the source of examples of both types of private issues - coupons for use in the tienda de raya and emergency currency printed during the revolution.

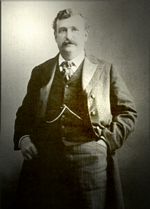

Its developer, William Cornell Greene, was born in Duck Creek, Wisconsin in 1851. In the 1890s he became interested in Sonora and secured from Governor Pesqueira’s widow an option on the Cobre Grande group of mines. He raised the money with a dubious prospectus and in September 1899 organised the Cananea Consolidated Copper Company and its parent, the Greene Consolidated Copper Company. Cananea became the leading mining centre of Mexico. With 25,000 inhabitants, it was one of the biggest cities of Sonora, enjoyed one of the highest percentages of growth in Mexico, and until 1907 benefited from the boom in copper. In 1906, in order to raise additional capital and expand operations, Greene entered into a partnership with Thomas F. Cole, a well-known copper entrepreneur. Together they formed the Cananea Central Copper Company. The same December they formed the Greene Cananea Copper Company which controlled both the Cananea Central Copper Company and the Greene Consolidated Copper Company. In February 1907 Cole and his associate from the Anaconda Corporation, John D. Ryan, wrested control of the Greene Cananea Copper Company from Colonel Greene, who had no subsequent involvement in operating the Cananea mines.

Its developer, William Cornell Greene, was born in Duck Creek, Wisconsin in 1851. In the 1890s he became interested in Sonora and secured from Governor Pesqueira’s widow an option on the Cobre Grande group of mines. He raised the money with a dubious prospectus and in September 1899 organised the Cananea Consolidated Copper Company and its parent, the Greene Consolidated Copper Company. Cananea became the leading mining centre of Mexico. With 25,000 inhabitants, it was one of the biggest cities of Sonora, enjoyed one of the highest percentages of growth in Mexico, and until 1907 benefited from the boom in copper. In 1906, in order to raise additional capital and expand operations, Greene entered into a partnership with Thomas F. Cole, a well-known copper entrepreneur. Together they formed the Cananea Central Copper Company. The same December they formed the Greene Cananea Copper Company which controlled both the Cananea Central Copper Company and the Greene Consolidated Copper Company. In February 1907 Cole and his associate from the Anaconda Corporation, John D. Ryan, wrested control of the Greene Cananea Copper Company from Colonel Greene, who had no subsequent involvement in operating the Cananea mines.

Like the other major American mining companies the Cananea Consolidated Copper Company operated a tienda de raya but settled on paydays with paycheques or cash. For many workers the final payout was low: the cheques on display in the Museum at Cananea show an average monthly wage of twenty-eight pesos but with average deductions for rent, hospital insurance, goods purchased on credit, fiestas, etc. of $27·75 leaving just 25 centavos to be paid out.

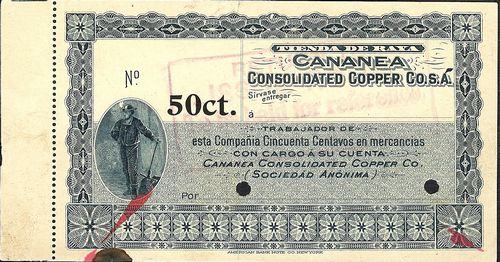

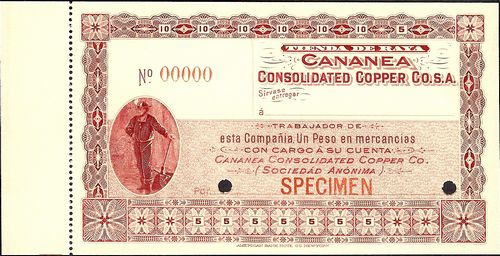

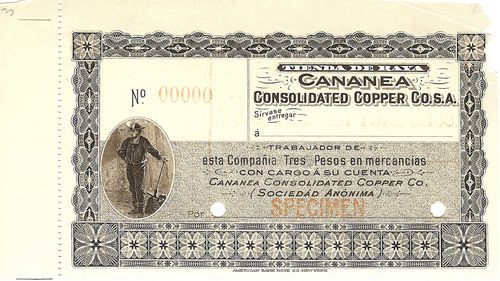

The company’s tienda had a working capital of 180,000 pesos and annual sales of 145,000 pesos. The tienda operated a check-off scheme by which the company gave workers scrip (boletos)[image needed] to be exchanged in the tienda for merchandise. In 1902 the boletos had the legend Tienda de Raya / Consolidated Consolidated Copper Co., S.A. / Sirvase entregar a _______________________ / Trabajador de esta Compania / _______ pesos en mercancias con cargo a su Cuenta. / Cananea Consolidated Copper Co., S. A. and were probably printed by the Ketterlinus Lithographic Manufacturing Company of Philadelphia{footnote}CCCC papers, letter from George Robbins, New York to John A. Campbell, Cananea, 9 June 1903{/footnote}.

The company argued that it did not use the boletos as currency. “… with us they constitute merely a certificate that a certain workman has performed certain labour and has a balance due him of a certain amount. Each ticket as issued is properly stamped and none are reissued after having been taken in by the Mercantile Department. Another reason why it is necessary that we use something of this character is the absence of small coin for change. There being no mint in this State, it would be a very difficult matter for us to provide adequate coin for change were the use of boletos here abolished"{footnote}CCCC papers, folder 1, letter from A. W. Burchard to A. C. Bernard, Hermosillo, 28 April 1902{/footnote}.

In April 1902 a complaint was made to the Federal government that the company was paying its workers other than in efectivo, in contravention to the law, and an investigation ordered through the District Judge at Nogales. The company consulted its lawyer, licenciado Pesqueira, who had had considerable experience in defending other mining companies in similar circumstances. Pesqueira reported that the usual policy of the government was to allow matters to run along until a complaint was made, then to order an investigation and impose a fine, after which the company would continue as usual until further agitation. He did suggest, however, that the company change the legend from ‘en mercancias con cargo á su cuenta’ to ‘en mercancias con cargo a nuestra cuenta’ , as this complied as near as possible with the law. The judge referred the matter to Mexico City so the company asked its lawyer in Mexico City, Tomás Macmanus, to lobby the federal authorities{footnote}CCCC papers, folder 1, letter from A. W. Burchard to Tomás Macmanus, Mexico City, 5 May 1902{/footnote}.

50c without denomination

$1 without denomination

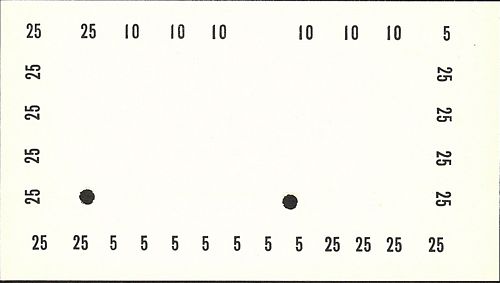

At this very time the company was negotiating with the American Bank Note Company for a new series of boletos. Proofs (50c blue, $1 red, $3 brown, $5 green on white card and green on cream card and $10 purple) dated June 1902 and January 1903 are known. These notes had a sequence of values on the face or reverse so that the purchases could be checked off until the card was completely used. Burchard wrote to ask whether the company could make the proposed change without damaging the plates: otherwise it would use the existing plates{footnote}CCCC papers, folder 1, letter from A. W. Burchard to Philip Berolzheimer, New York, 19 May 1902{/footnote}. So the issued notes could have had either the earlier or the revised text.

In 1903 the greater portion of paymaster’s cheques delivered to employees at the outlying camps were cashed by brokers. This resulted in a considerable loss to the employees, in the exorbitant rates of exchange charged, and to the company, in the loss of exchange and deposits for the company’s bank. The outside brokers did a considerable business in advancing money on identity cards (carteras) as there was a long wait between pay-days and, as the company manager George Young acknowledged, it would have been too much to expect the general run of employees to wait for their pay in regular course. The company did occasionally advance money to employees between paydays but did not encourage them to ask for such advances. As the brokers at the outside camps charged interest at 5% to 10% per month, Young suggested that it would be possible to protect the men and profit the company by advancing to a broker sufficient money to carry on the business, advances to be made on a regular schedule of rates{footnote}CCCC papers, letter from George Young to James H. Kirk, 17 March 1903{/footnote}.

By November 1905 the company could claim that the employees were paid in cash and could buy goods where they liked{footnote}El Paso Herald, 15 November 1905{/footnote} but at the time of the 1906 strike{footnote}The strike at Cananea was one of the events that set the stage for the rebellion of 1910. The strike was caused by declining export markets, fear of unemployment, and fear and envy of foreigners. Cananea employed 5,360 Mexicans and 2,200 foreigners, mostly Americans. No one disputed that Greene paid the highest wages in Mexico (to quote Governor Izábel, the miners dressed in the clothes of the middle class, equipped their homes with modern appliances, and purchased the latest furniture) but judged by the income of miners in Arizona and by the income of the Americans at their own mines, Mexicans fared poorly. Nor did Mexicans enjoy job security, which occurred only with high copper prices: the collapse of the copper market in 1907 meant that miners lived with the fear of unemployment. On 31 May 1906 the night shift at the Oversight went on strike. The next day workers at Capote and Veta Grande mines, the smelter and the concentrator followed suit. A delegation presented demands that focused directly on conditions in the mines: the dismissal of a foreman at the Oversight mine; a reduction of working hours from nine to eight; a basic wage of five pesos; promotion for Mexicans according to their abilities; and a new rule that, where abilities were equal, the workers in any given division should be 75 percent Mexican and 25 percent non-Mexican. These demands were incorporated into a manifesto which attacked Díaz’ dictatorship as an ally of foreign employers. The same evening, three thousand strikers marched through the streets of Cananea, waving Mexican and a few red flags and holding placards which proclaimed ‘Five pesos for eight hours!’ The demonstrators successfully called on those still at work to join the strike, so that a total of 5,300 miners were involved in the movement. Accounts over what followed differ, but there was some fighting between company guards and the strikers in which the lumberyard manager, George Metcalf, his brother Will and three strikers were killed. The battle raged for two days between, on the one hand, workers poorly armed with rifles and pistols which they had seized, almost without ammunition, in an assault on the company store, and on the other hand, well-armed federal troops backed by a 275-strong battalion of United States ‘rangers’ who crossed the border from neighbouring Arizona at the invitation of governor Izábel (though they took no part in the dispute). Before the strike subsided, half a dozen Americans and thirty Mexican miners had died. This invasion of Mexican soil by armed Americans raised a public outcry. Madero publicly condemned the use of American mercenaries to squash the strike at Cananea. Díaz, he said, should have compelled the owners to pay higher wages. After the strikers were defeated, their leaders received long prison sentences and were only freed by the revolution.{/footnote} the Flores Magóns' newspaper Regeneración claimed that whereas Americans were paid in cash, Mexicans were paid in boletos for the company’s tiendas de raya, where shoddier goods were sold at prices two or three times higher than normal. When a Mexican worker needed to change his boleto into cash, the company redeemed them for 75% of their value{footnote}Regeneración, 15 June 1906. These claims were in fact compatible. Cananea lies 62 kilometres south of the United States border and most of its consumer goods, including staple foods, were imported. In 1905 the Mexican devaluation of the peso by 50% devastated the real wages of the miners. They faced the immediate loss of half of their buying power because the company insisted on paying them in Mexican and non-gold based scrip instead of gold or US dollars. American employees were paid in US currency (and enjoyed higher wages to begin with).{/footnote}.

As a result of the financial crisis of 1907 the Cananea Consolidated Copper Company began laying off workers in September, ceasing all operations by the year's end{footnote}"No se deben alarmar," Heraldo de Cananea, 30 September 1907{/footnote}. In the words of one observer, "long wagon-trains, burros-trains, and people on foot are pouring down the 60 miles of highway from Cananea to Imuris . . . penniless . . . not knowing how they are going to feed themselves on their long journeys to distant homes”{footnote}Mining and Scientific Press, 16 November 1907{/footnote}. As news of the mine closures reached Nogales, Manuel Mascareñas reported that officials had been forced to close the Bank of Sonora as panicked depositors demanded their money{footnote}AER, Copiadora, Julio 1906/Enero 1911, 15 September 1907, Manuel Mascareñas to Max Müller{/footnote}. The mine remained closed until the summer of the following year.

By 1908 the company had been fined two or three times and finally ordered to discontinue the use of boletos. The matter was laid before the Secretaría de Hacienda in Mexico City, and the Secretario or Sub-secretario drafted a new form of wording. The company was told that they could use this as a libreta or little book, in other words as a substitute for a pass book. In September 1908 the Greene Gold-Silver Company in nearby Temosachic, Chihuahua, was fined for using an identical libreta and the general manager, George Young, suggesting again using Tomás Macmanus to lobby the Secretaría de Hacienda{footnote}CCCC papers, folder 5, letter from Young to L. D. Ricketts, 8 September 1908{/footnote}.

In 1910 Young wrote that the company had one regular pay-day or final settlement day each month, but all of the employees were at liberty to draw food supplies, merchandise, meat etc. daily on their accounts and could draw cash once in each week in addition to their final settlement. The pay department was open every day for this service except Sunday, but the same man was not permitted to draw cash more often than once in each week{footnote}CCCC papers, letter from Young to R. G. Dun and Co., Guaymas, 29 June 1910{/footnote}. By 1913 the Prefecto of Cananea could report that the company had paid in banknotes and silver coins for several years{footnote}AGHES, Fondo Oficialidad Mayor, tomo 2971, telegram, 23 September 1913{/footnote}, but he was hardly an impartial commentator.

As stated, as a result of the collapse of the market for copper in 1907, the mines at Cananea were shut down. Although some were partly reopened the next year, Greene himself admitted that the jobless filled the streets of Cananea. By 1911, Cananea had lost two-fifths of its inhabitants, and not until that year did its mines pay dividends to their shareholders. On 9 May 1911, Cananea fell to Juan Cabral and his men, the first city in Sonora to be captured by rebels. Greene himself was killed in a buggy accident in 1911 whilst relocating to the United States in the face of revolutionary activity.

The Cananea company suspended operations from August 1914 to June 1915 and again from June to December 1917, because of the depressed copper market and the constraints imposed by the Constitutionalist government. In 1917 the assets of the Greene Consolidated Copper Company were sold to the Greene Cananea Copper Company and the former dissolved the following year. The Cananea Consolidated Copper Company continued to operate as a Mexican subsidiary of the Greene Cananea Copper Company.

Cananea is one place suggested as the origin of the word 'bilimbique'. It is said that local businesses would accept the company’s chits (vales) if they had been signed by the cashier, an American called William Weeks, which the Mexicans pronounced ‘Biliam Biqs’ and the notes soon became ‘bilimbiques’{footnote}The Numismatist, October 1915. Other explanations mention a William Wicke of the mine La Veladeña in Durango; William Vicks, an American miner in Sonora with his own tienda de raya (Tim Turner of Associated Press, quoted in I. Thord-Gray, Gringo Rebel (Mexico 1913-1914), Miami. 1960), or ‘Billis Ticket’, a name given the vouchers of the Cananea mining company{/footnote}. Later the name was applied to any vale or note of dubious value and during the revolution it was applied to the Constitutionalist currency.

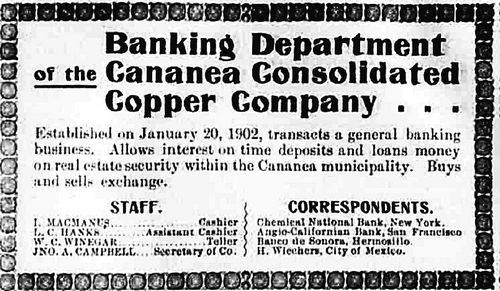

In 1901 the Cananea Consolidated Copper Company was paying by cheques drawn on the Banco de Sonora but the next year without any official authorisation it established its own bank.

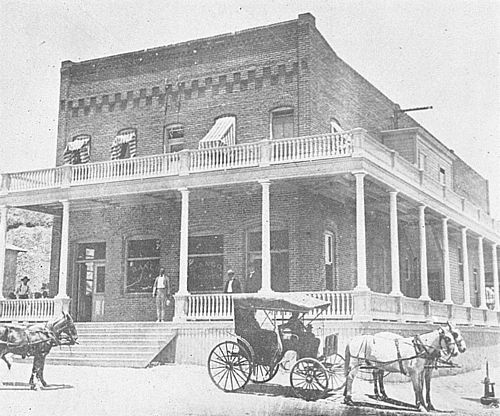

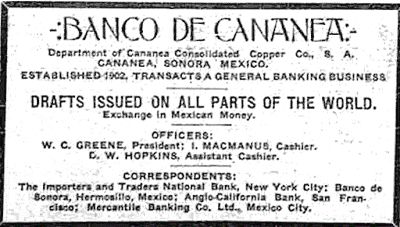

Banking Department (The Oasis, 8 March 1902)

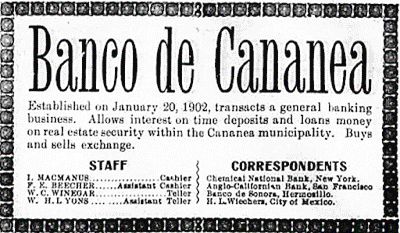

Banco de Cananea (The Oasis, 23 August 1902)

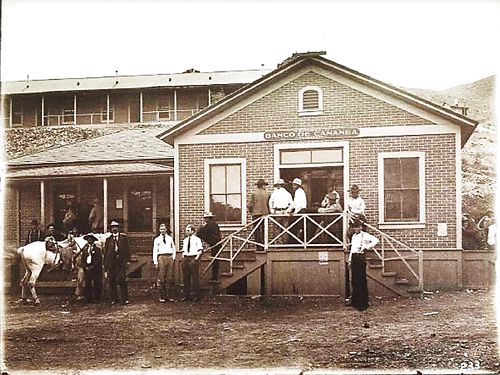

The Banco de Cananea S.A. was set up on 20 January 1902, with a capital of $200,000, taking over the operation of the company’s banking department. The bank was housed in the same two-storey building as the general store and the general offices of the company{footnote}J.R.Southworth, Las Minas de México, Mexico, 1905{/footnote}.

By a presidential decree of 28 May 1903 the designation ‘Banco’ was limited to institutions established under the Ley General de Instituciones de Crédito of 1897. Existing corporations already using the name ‘Banco’ could continue to do so if they appended ‘sin concesión’. Hence in 1904 Paymaster’s cheques (made out to bearer with the employee named in the calculations) had the heading ‘Banco de Cananea / departmento de la Cananea Consolidated Copper Company S.A.’ but by 1905 carried an altered heading ‘Banco de Cananea / sin concesión / department of the Cananea Consolidated Copper Company S.A.’ and were drawn on the Anglo-Californian Bank, San Francisco.

Banco de Cananea (Bisbee Daily Review, 27 August 1907)

The Banco de Cananea continued to operate until at least 1911. During the 1906 strike, it was reported that over 65 percent of the miners had savings on deposit, totalling approximately 40,000 pesos, in the bank{footnote}AGHES, tomo 2184, Año 1906, exp. Huelga de Cananea letter to Corral, 8 June 1906{/footnote}. It went into voluntary liquidation in April 1911 because local business conditions made it unprofitable{footnote}CCCC papers, letter Young to Macmanus, 6 March 1911: El Paso Herald, 4 March 1911{/footnote} even though it was written up in the El Paso Herald of November 1911.

It conducts a general banking business, offering its patrons special facilities for the transacting of business to and from the United States. They buy and sell exchange and issue drafts on all parts of the world. It is conducted upon the soundest and most conservative business principles and has won a deserved reputation throughout this section for its stability and standing in the banking world. Its president is the well known and wealthy capitalist and mine owner, Col. W. C. Greene. Its cashier I. Macmanus, a representative citizen of Cananea for years identified with its business interests, is a gentleman thoroughly schooled in all branches of the banking business and is popular with the many patrons of this progressive bank. He is ably assisted by D. W. Hopkins, assistant cashier, a young man experienced in the business and with a wide circle of friends{footnote}El Paso Morning Herald, 15 November 1911. That this encomium was written earlier is shown by the fact that by November 1911 Colonel Greene had been dead for four months{/footnote}.

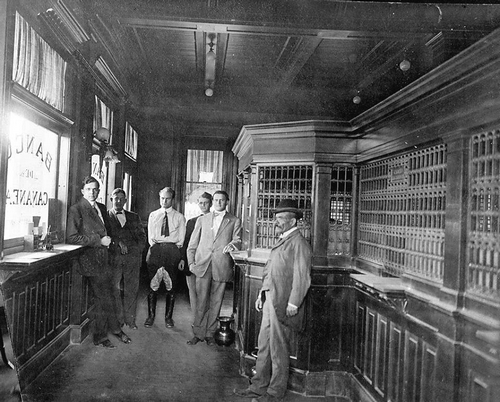

Interior of the Banco de Cananea (1907-1908)

Branch at Chivatera, 1906

Amongst the employees of the bank were:

Frank E. Beecher: from the Bank of Bisbee, assistant cashier at Cananea, then manager of the bank’s branch at Temosachic, Chihuahua from its opening on 7 January 1907 until its closure on 18 May 1907{footnote}The business continued as the banking department of the Sierra Madre Land and Lumber Co., Madera (CCCC papers). It is reported that the bank also established a branch in the Chihuahuan town of Madera (with a round plaque saying ‘Banco de Cananea S.A. Capital $15,000,000’).{/footnote}.

A. S. Dwight: general manager in 1906{footnote}The Cananea Herald, 21 July 1906{/footnote}.

L. C. Hanks: assistant cashier in February 1902{footnote}Tucson Daily Citizen, 28 February 1902{/footnote}.

D. W. Hopkins: assistant cashier, resigned in November 1910{footnote}El Paso Herald, 29 November 1910{/footnote}.

W. H. Lyons: assistant teller in 1902{footnote}The Cananea Herald, 28 September 1902{/footnote}.

Ignacio Macmanus González had been manager of his family’s bank, the Banco de Santa Eulalia in Chihuahua, from at least 1890 until at least 1893. The family lost its fortunes in the 1890s and both Ignacio and his brother Tomás, a solicitor, worked for the Cananea Consolidated Copper Company. Cashier of the Cananea Consolidated Copper Company (Banking Department) by 1902 and first manager of the Banco de Cananea in 1902, Macmanus was also Presidente Municipal of Cananea from 1903 to 1905. On the night of 31 May 1906 at the start of the strike Macmanus left Cananea for Hermosillo to inform governor Izabel and request troops.

Ignacio Macmanus González had been manager of his family’s bank, the Banco de Santa Eulalia in Chihuahua, from at least 1890 until at least 1893. The family lost its fortunes in the 1890s and both Ignacio and his brother Tomás, a solicitor, worked for the Cananea Consolidated Copper Company. Cashier of the Cananea Consolidated Copper Company (Banking Department) by 1902 and first manager of the Banco de Cananea in 1902, Macmanus was also Presidente Municipal of Cananea from 1903 to 1905. On the night of 31 May 1906 at the start of the strike Macmanus left Cananea for Hermosillo to inform governor Izabel and request troops.

W. C. Winegar was a teller in 1902{footnote}Tucson Daily Citizan, 28 February 1902: The Cananea Herald, 28 September 1902{/footnote}. Winegar went on to be appointed manager of the Chihuahua branch of the Banco de Sonora in August 1906{footnote}El Correo de Sonora, 17 August 1906{/footnote} and, after the revolution, vice-president and manager of the Sonora Bank and Trust.