A new unlisted Mexican note tied to Maximilian

by Ricardo de León Tallavas

Every catalog of Mexican paper money refers to the first issue west of Chihuahua and north of San Luis Potosí as being printed in Tamaulipas in 1876 by Servando Canales. However, this fact is now erroneous as we are about to see. The State of Nuevo León had issued similar bonds as those of Tamaulipas but nine years previously and while the war between Juárez’s Republic and Maximilian’s Empire was still being fought.

This forgotten issue of paper money was vaguely discussed for the first time in Monterrey, capital of the state of Nuevo León, on 6 March 1867. The Official Gazette (Periódico Oficial) stated that the reason for a possible issue of some public bonds was the absolute need of liquid cash. It added that these bonds would be exchangable in public hands (just like paper money). The lack of cash on the streets of Monterrey was also prevalent in the rest of the state, so it was an immediate priority to find a solution to satisfy the public’s demand: to attend to the most immediate challenges that the region was suffering as a direct effect of the war against the dying Empire: a loan had to take effectPeriódico Oficial, vol I, núm. 58, 6 March 1867.

Less than a month later, in the 3 April issue of the Periódico Oficial, the editorial described again the dire economic situation in the state of Nuevo León, and how great efforts from the Republic were being made to support the final defeat of Maximilian and of his “ten or eleven thousand forces composed of traitors and their notorious commanders set in Querétaro”. The transcription of a call to gather every resource to aid on this last and final step against Maximilian’s Empire by every corner of the country appeared right after. Then the focus of this editorial switches to the blatant need for some form of money in Nuevo León, and the high rates that a loan concerted by a commercial business would represent to the state’s Treasury. The first news of an internal loan in the manner of a public circulation of bonds, payable on demand of the bearer, was mentioned in writing as a concrete thought. This editorial stated that these bonds would be taken as public notes to be circulated without any discount and would be valued the same as hard cash. This editorial was the introduction of what was about to be inserted in the next paragraphPeriódico Oficial, vol. I, núm. 65, 3 April 1867.

This editorial is followed by the decree of issue for these bond-notes, passed by the State’s Congress and dated on 27 March 1867. The decree begins by stating that various series of bonds were going to be issued for a total of 100,000 pesos. The First Series was going to be exactly in the amount of 22,704 pesos, leaving the other issues to be determined at a later time (which never happened). So, the total amount for this “First Issue” is surprisingly very specific, and at first glance an odd number. There is a reason for this very specific amount: it was the exact amount needed to pay the government’s employees (the main reason for these public bonds) and the soldiers in the area. They were going to be distributed in all 41 important municipalities in Nuevo León, the highest amount being for Monterrey, with 6,000 pesos. The smallest amount of these bond-notes to be distributed was barely 66 pesos, sent to seven of those municipalities, including Galeana and Mier y Noriega. Interestingly, the list includes the town of Valladares, now in Coahuila, which back then was part of Nuevo LeónIbidem. The complete list was

Monterey $ 6,000

Cadereita Jimenez “ 2,200

Montemorelos “ 2,200

Linares “ 2,200

Salinas Victoria “ 1,100

Terán “ 1,100

Villa García “ 660

Santiago “ 660

Villaldama “ 550

Sabinas “ 440

Lampazos " 440

Guadalupe “ 330

Galeana “ 220

Dr. Arroyo “ 220

Cármen “ 220

Apodaca “ 220

Cerralvo “ 220

China “ 176

Rayones “ 176

Marin “ 176

Abasolo “ 176

Santa Catarina “ 176

Hualahuises “ 176

San Nicolas Hidalgo “ 176

San Nicolas de los Garza “ 176

Pesquería-Chica “ 176

Mina “ 176

Allende “ 176

Bustamente “ 176

Vallecillo “ 110

Agualeguas “ 110

Zuazua “ 110

Ciénega de Flores “ 110

San Pedro de Iturbide “ 110

Los Aldamas “ 66

Higueras “ 66

Parás “ 66

Rio-blanco “ 66

Zaragoza “ 66

Mier y Noriega “ 66

Valladares “ 66

$22,704

though the total is in fact $22,104 which suggests a typo in the Periódico Oficial and that Monterey was in fact assigned $6,600.

Article 3 commanded that the bonds would earn a monthly interest of 2%, which makes it an extremely high rate, an unheard 24% annually! This rate leads anyone to believe that the plan was to liquidate these bonds in cash as quickly as possible and, hopefully, with some of its redemption coming from some silver coins sent by the federal government in Mexico City. The 2% rate would start after 1 May, so it could also be concluded that these bonds were issued extremely quickly, right after the decree of 27 March, and more than likely by 1 April 1867. So 1 May would be an exact month after their issue to the publicIbidem.

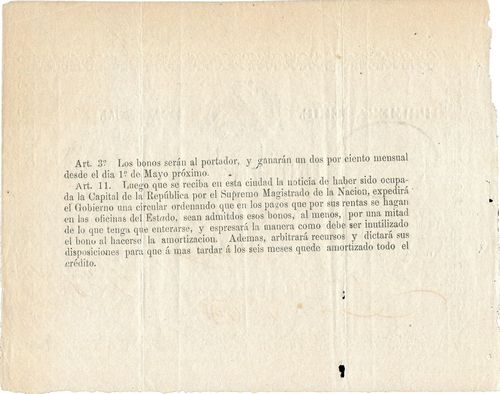

Article 4 is, in my opinion, the most frustrating wording as often found in the Archives in Monterrey when it comes to any mention of any numismatic issue. It states: ”The Treasury will compose the artistic model with the elements that it sees fit to make these bonds”, being the only mention of their design with nothing else afterwards. If an example had not survived, we would have no idea of their appearance. Article 5 establishes that the reverse of these bonds would bear in print the wording of Articles 3 and 11, so people would understand the validity and the way on which these bonds would be cancelled and paid. Article 11 mentioned some legal and redemption ties to Mexico City, showing a congruence to the situation of a common side effect of any war, the lack of currency, the reason that created these public bonds. It is worth mentioning that having a reading on the reverse on any paper money issue in Mexico at that or any other earlier time is very rare, as usually the reverse was left blank purposely to be used for annotations during the bond’s circulation or redemptionIbidem.

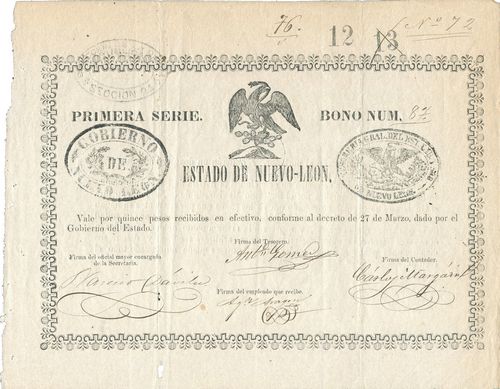

M38 $15 Estado de Nuevo León

M38 $15 Estado de Nuevo León

| from | to | total number |

total value |

||

| $1 | |||||

| $2 | includes number 2793 | ||||

| $5 | |||||

| $10 | |||||

| $15 | includes number 87 | ||||

| $20 | |||||

| $25 | |||||

| $22,704 |

The bond I have for 15 pesos is unique to that denomination, but there is another known example for this First Series, bearing the denomination of two pesos. This other note (number 2793) was the first known specimen of this forgotten series, and was auctioned in Mexico City in 2007, without any historical background on its description other than to assert that it was “circa 1860”. Fourteen years later the 15 pesos note surfaced. It bears the number 87, and is similar in all respects to the two pesos note, except that the denomination is different. The bond measures about 220 × 138 mm and this specimen seems to be the one printed on the right top corner of the full page, calculating eight notes per page or so, perhaps divided in four items in each of the two columnsDuane D. Douglas, Auction of El Mundo de la Moneda, Hotel del Prado, Mexico City, 15/16 March 2007, lot 341.

The two known bonds bear two generic stamps of origin and both are oval shaped. The one on the left reads: ”GOBIERNO DE NUEVO LEON” (Government of Nuevo Leon); the one of the right reads: “TESORERIA DEL EST. LIB. Y SOB. DE NUEVO LEON” (Treasury of the Free and Sovereign State of Nuevo León), alluding to the Republican nature of this issue. However, both known bonds bear an extra stamp that is different from one another. The two pesos note has an oval shaped with the name of Monterrey, which more than likely speaks of the place of its redemption in cash.

The fifteen pesos note has a stamp seal applied in Mexico City (22 June 1885) which would explain this note being accepted and redeemed then and there as part of the Second Section of Public Debt (Consolidated Internal Debt that was deferred, issued legally but pending payment). They added a circular punch to cancel this note usually seen in other financial documents bearing this 1885 stamp. If this was the case, this bond originally issued for a mere 15 pesos was redeemed after 18 years, according to the terms stated on its reverse for at least 79.80 pesos!

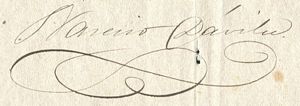

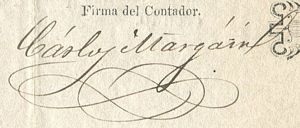

The First Series bond-notes had four signatures, one of the State’s Government Secretary (Narciso Dávila), another of the Comptroller (Carlos Margáin), another of the Treasurer and the fourth would be added by the first recipient of this note. This last signature was very important because it gave a traceable start in the chain of circulation, it could track every note issued to the public and it would prevent any possibility of “lost bonds” on transit or any other ill situations. My assumption is that there was a record for these bond-notes. It is important to mention that this fourth signature also became proof that the money owed to a certain individual had been paid, something like a payroll signature. In the case of the 15 pesos note this signature was issued to pay a gentleman named Agustín Aragón, possibly a military member from the central-south of Mexico.

| Narciso Dávila de la Garza, the Secretary of the State’s Government, ended up being the Governor of Nuevo León in 1876 with the direct aid of then President Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada. Dávila spent most of his later life as a Senator. |  |

| In the weeks following the signing of these bond-notes, Carlos Margáin left Monterrey for Querétaro to help with his forces to defeat Maximilian. Margáin ended up being the one in charge of the escort of the most important prisoners of his times, Archduke Maximilian, Miguel Miramón and Tomás Mejía, from the time of their trial to their execution on 19 June 1867. Carlos Margáin ended up in this situation by the mere stroke of luck of his boss being ill and unable to perform this duty. If this reference was not enough to add historical value to this bond-note there is a very real numismatic fact attached to that signature: “In those instances Col. Palacios, the Officer in charge of his custody in the building where the emperor was held prisoner, entered Maximilian’s cell. Palacios was in the company of Lieutenant Colonel Margáin. Maximilian thanked both for their attentiveness towards him and the rest while displaying their military duty, giving five ounces of gold with the Imperial designs and arms to Margáin in order for him to forward these gold coins to the soldiers that would shortly execute him”Blasio, José Luis. Maximiliano íntimo: el Emperador Maximiliano y su corte: memorias de un secretario particular. México, Vda de C. Bouret, 1905. p.398. For more on these coins, see Maximilian's Execution.. |  |

| Antonio Gómez Valdez |  |

We are uncertain of all the denominations of this First Series as the decree just mentions the amount (22,704 pesos) and the reason for issuing them. However, there are some scattered notices of a few of these bond-notes being redeemed in cash which brings some light to this specific question. On 13 July 1867 it was stated that “six bonds of the First Series were paid in the amount of 150 pesos”, which implicitly speaks of 25 pesos each. On 12 October 1867 it was stated that another bond of the First Series had been redeemed “by superior command” in the amount of 20 pesos. Why was this bond redeemed “by superior command”? My assumption is that by then these bonds were not any longer being automatically cashedPeriódico Oficial, Monterrey, Nuevo León, vol I, no. 94, 13 July 1867.

So, besides this bond of 15 pesos we have the two pesos note auctioned in 2007, and we can assume that notes of one peso could have been printed for it was the base of any transaction. Then we could speculate that the five and ten pesos are very likely to have been part of this set. Then the 20 and 25 pesos are also known as a fact to have been part of the First Series because they were mentioned as being redeemed. We could also speculate about the possibility of a 50 peso note: however, in my opinion, this is highly unlikely. So the series more likely looked like this: 1, 2, 5, 10, 15, 20 and 25 pesos, with the proved referenced denominations being in boldPeriódico Oficial, vol II, núm. 19, 12 October 1867.

The last known mention of these bond-notes of the “First Series” happened on 22 February 1868, within the articles of the decree number 13 signed by Governor Gerónimo Treviño. In Article 15 it states that the Nuevo León’s State’s Government agreed to receive these bonds issued on 27 March 1867, for up to 20% of any tax payment, including the running interest. Interestingly, Narciso Dávila was still the Government’s Secretary. As history has proven time and time again, the usual initial promise of any official paper money to be redeemed as cash fell on to it being received merely as a portion of payment of a tax dueColección de leyes, decretos, circulares y documentos oficiales del Gobierno del Estado, expedidos desde noviembre de 1867 hasta febrero de 1869, Imprenta del Gobierno, Monterrey, 1882, p.62.