The Columbus-Native Woman Vignette on Mexican and other Currencies

by Peter S. Dunham, Ph.D.

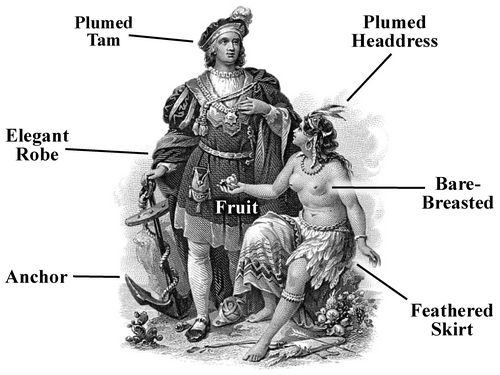

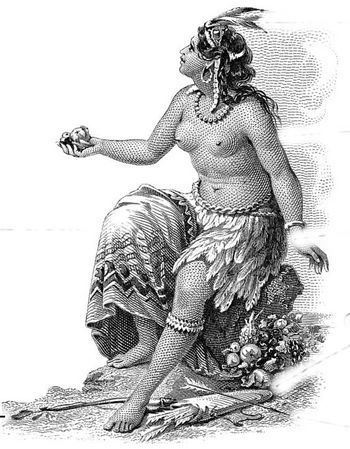

In this article I explore the significance of the American Bank Note Company (“ABNC”) vignette of Columbus and a Native American woman initially engraved by Charles Burt in 1868. The original, basic version is distinguished by the elegantly robed Columbus standing at left, staring distantly, sporting a tam with plume, his right hand resting on an anchor to the left, an astrolabe and chart at his feet. Offering him a handful of fruit, the semi nude native woman sits at his side to the right, gazing up at him, wearing a plumed headdress, jewellery, and feathered skirt, a blanket draped on her right knee, quiver, bow, arrow, and bunch of fruit at her feet. The die proof is labeled “Columbus,” confirming the explorer’s identity.

In this article I explore the significance of the American Bank Note Company (“ABNC”) vignette of Columbus and a Native American woman initially engraved by Charles Burt in 1868. The original, basic version is distinguished by the elegantly robed Columbus standing at left, staring distantly, sporting a tam with plume, his right hand resting on an anchor to the left, an astrolabe and chart at his feet. Offering him a handful of fruit, the semi nude native woman sits at his side to the right, gazing up at him, wearing a plumed headdress, jewellery, and feathered skirt, a blanket draped on her right knee, quiver, bow, arrow, and bunch of fruit at her feet. The die proof is labeled “Columbus,” confirming the explorer’s identity.

I employ two fairly straightforward concepts in my analyses of imagery on paper money:

1. “Visual Linguistics” – I read Mexican banknotes like Western texts, from front to back, left to right, and top to bottom, with the images accented by size, position, or framing, establishing an order and even a hierarchy of symbols.

2. The “Imaginario” – a group of images, visual, textual, or verbal, arranged to project a desired association, similar to how a photo mosaic or photo array on social media evokes an overarching theme.

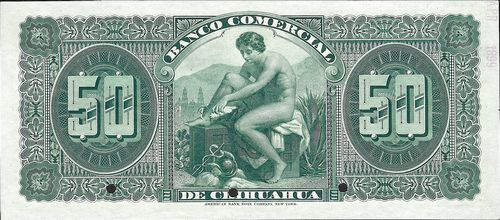

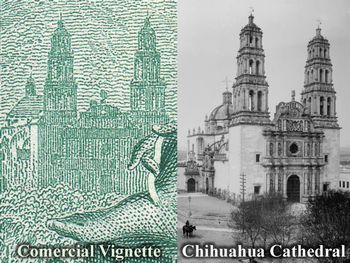

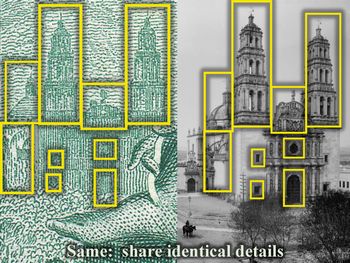

The Banco Comercial de Chihuahua 50 pesos has three vignettes, two on the front and one on the back. On the front a portrait of Hidalgo, hero of independence, is in the lead position, first from left at center, in a scrolled frame captioned “Chihuahua,” where Hidalgo died, while the Columbus-native woman vignette is secondary, at front right without a frame but considerably larger than Hidalgo. A large allegory of Commerce (the god Mercury with his winged helmet, sandals, and caduceus sitting on a cash box) framed by the bank’s name (Comercial) is tertiary at back center. Mercury is flanked by Mexican motifs: a nopal cactus. maguey and the Cathedral in Chihuahua (based on Henry William Jackson’s photograph).

America

Returning to our focal vignette, the native woman symbolizes America or the Americas. With her plumed headdress, bow, arrow, quiver, feathered skirt, cape, and bare torso, she reprises the widely embraced avatar of the Americas from the four continent allegories formalized by Ripa in 1603. The same icon was broadly employed to signify America and even the US in paper money vignettes from the 1800s and she was also adapted to embody a number of American countries on medals and coins, as I have shown in my article “Native Identity and Independence on the Chihuahua Coppers of the First Republic”.

Returning to our focal vignette, the native woman symbolizes America or the Americas. With her plumed headdress, bow, arrow, quiver, feathered skirt, cape, and bare torso, she reprises the widely embraced avatar of the Americas from the four continent allegories formalized by Ripa in 1603. The same icon was broadly employed to signify America and even the US in paper money vignettes from the 1800s and she was also adapted to embody a number of American countries on medals and coins, as I have shown in my article “Native Identity and Independence on the Chihuahua Coppers of the First Republic”.

Europe/Spain

With the Native American woman signifying America, what would Columbus represent? In keeping with her example as a continental allegory, he undoubtedly personifies Europe in general. Sailing under the Spanish flag as a native of Genoa, Italy, he also stands for Spain in particular and perhaps even Italy.

With the Native American woman signifying America, what would Columbus represent? In keeping with her example as a continental allegory, he undoubtedly personifies Europe in general. Sailing under the Spanish flag as a native of Genoa, Italy, he also stands for Spain in particular and perhaps even Italy.

Together the figures signal the encounter between the “Old” and “New Worlds”, but as America presents her fruits (resources) to Europe/Spain, his gaze is fixed beyond her as if he is looking for more than just fruit.

Sources for the vignette

The Columbus-America vignette builds on a long artistic history of pairing such figures. For example, Galle’s engraving of c1600 features a Columbus-like Amerigo Vespucci standing before America seated on a hammock, Persico’s 1844 statue, formerly at the east portico of the U.S. Capitol, has a triumphant Columbus looming over a cowering America stripped nearly naked, whilst Vela’s bronze in Colón, Panamá, which debuted at the 1867 Paris Exposition, presents a towering Columbus comforting a traumatized America.

However, the ABNC vignette draws directly from two monumental sculptures in Lima, Peru and Genoa, Italy, both designed by Salvatore Revelli:

• they share the same composition as the vignette but reversed; it was probably engraved as seen and flipped when printed;

• the 1860 statue in Lima clothes a standing Columbus in tam and finery nearly identical to the vignette and equips a seated America with her arrow and quiver, looking up at Columbus, like the vignette,

• the 1862 marble in Genoa introduces the anchor to Columbus and fruit to America.

With vignette artists unlikely to visit far-off statues, photos and engravings predating the 1868 vignette were probably used as models:

• Lima – Courret released a promising photo (1860s) and Semino published a litho (1855) in Michelangelo, both sharing the same aspect as the vignette.

• Lima – Courret released a promising photo (1860s) and Semino published a litho (1855) in Michelangelo, both sharing the same aspect as the vignette.

• Genoa – there were multiple images, a number comparable in aspect to the vignette, like Sommer’s stereoview (c1862-66) and the woodcut (1850s) in Leipziger Ilustrierte Zeitung.

• Genoa – there were multiple images, a number comparable in aspect to the vignette, like Sommer’s stereoview (c1862-66) and the woodcut (1850s) in Leipziger Ilustrierte Zeitung.

• Colón – the Michelez photo from the 1867 Paris Expo and the Blanadet-Jonnaro woodcut (1867) in L’universo illusrato again offer aspects similar to the vignette

• U.S. Capitol – the Bell stereoview (1867) and Best-Leloir woodcut (1845) in Le magasin pittoresque provide helpful likenesses.

Paper Money Applications

The Columbus-America vignette was used on banknotes of nine countries in mainland Spain and throughout the Americas, including Mexico. In all cases the vignette is either primary or secondary, always on the front, and when secondary, it is usually accentuated by being larger and/or in a frame.

The associated notes are generally among the highest denominations in their series, placing an elevated value on the image and these high values also fostered its circulation among wealthier users and commercial institutions, such as banks.

Original Version

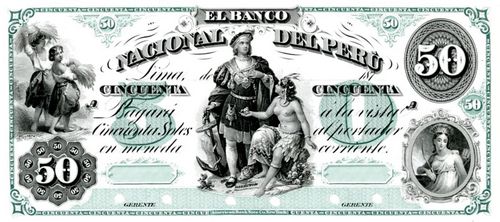

The vignette varied among applications, the initial variety (V-47313 591) being the basic one, Columbus and Native America alone, sans elaboration. Engraved by Burt in 1868, it was fi rst used on the Peruvian bill (50 pesos, El Banco Nacional del Peru) in 1872, four years later. This was not likely a custom order but probably also not random, either, as a main source image from which it was modeled, the Lima statue, is in Peru.

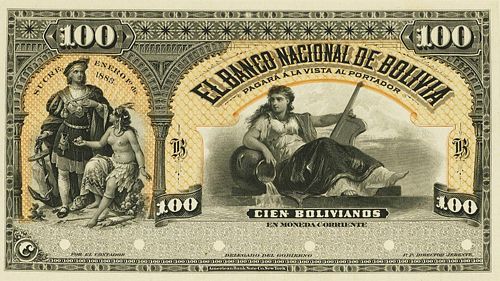

The vignette was heavily utilized. It also appeared on Colombian (100 pesos, Banco de Marquez, c1882), Bolivian (100 bolivianos, El Banco Nacional de Bolivia, c1883), and Venezuelan notes (100 pesos, Banco Comercial, c886), four of the full complement of nine (44%).

The original 50 pesos, El Banco Nacional del Peru

100 bolivianos, El Banco Nacional de Bolivia

Spanish Variant

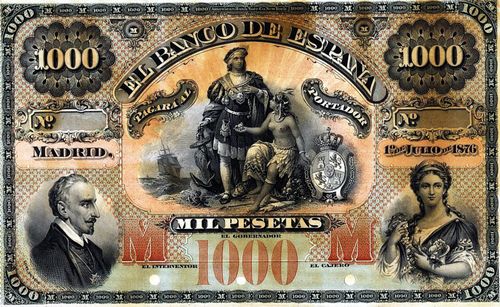

1,000 pesetas, El Banco de España

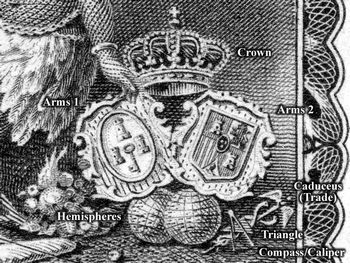

A second version of the vignette (V-47149 772) was developed for the Spanish note (1,000 pesetas, El Banco de España, 1876); engraved by William Charlton in 1875, it was “Spanishized”. A (Spanish?) sailing ship was added at left, at right the royal coat of arms of the Spanish monarchy from 1700 to 1931; the Spanish arms appropriate the scene for Spain and tag Columbus as the personification of Spain, not just of Europe and in the title “Reception of Columbus” the die proof hints that the Americas welcomed the Old World (Spain), painting imperialism in a sympathetic light.

A second version of the vignette (V-47149 772) was developed for the Spanish note (1,000 pesetas, El Banco de España, 1876); engraved by William Charlton in 1875, it was “Spanishized”. A (Spanish?) sailing ship was added at left, at right the royal coat of arms of the Spanish monarchy from 1700 to 1931; the Spanish arms appropriate the scene for Spain and tag Columbus as the personification of Spain, not just of Europe and in the title “Reception of Columbus” the die proof hints that the Americas welcomed the Old World (Spain), painting imperialism in a sympathetic light.

Other Banknote Variations

100 pesos, Banco de España y Rio de la Plata

50 centavos, El Banco Español de la Habana

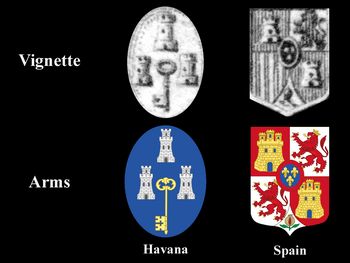

Other varieties are adaptations of the Spanish version, plus or minus national insignia The Dominican Republic (50 pesos, El Banco de la Compañía de Crédito de Puerto Plata, c1886) and Mexican bills employ the Spanish vignette but with the Spanish arms supplanted by vegetation at right; the Uruguayan (100 pesos, Banco de España y Rio de la Plata, 1888) note, issued by a joint Spanish-Argentine bank, maintains the Spanish arms at right but replaces the ship with the Argentine arms at left, whilst the Cuban bill (50 centavos, El Banco Español de la Habana, 1889) adds the arms of Habana to the Spanish arms at right, above two hemispheres, navigational aids, and a caduceus for commerce, all below a crown.

Relatively Long Lifespan

As vignettes go, this Columbus-America motif had a fairly long span of use and currency. Following its creation by Burt in 1868, its fi rst use on a banknote was in 1872 on the Peruvian note; it was utilized most heavily during the 1880s on six bills throughout Latin America, and its last appearance on a banknote was in 1898 on the Mexican note, 30 years after its original creation. It was resurrected as late as the 1970s on a stock certificate for Telefónica de España, over a century after its initial formulation.

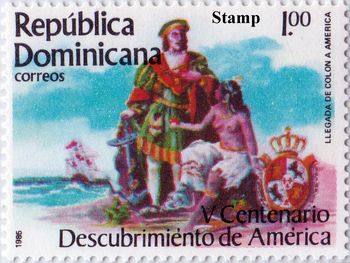

It also inspired a series of images in other media. Several brands of cigars produced for the World Fair of the Columbian quadricennial of 1893 in Chicago bore images on their labels that were based on it, where a native woman sits on right gazing up at and handing tobacco leaves to an elegant Columbus standing in center with anchor, backed by ship(s) at left. For the Columbian quincentenary, in 1985, the Dominican Republic released a postal stamp with a color version of the vignette.

Conclusions

The 50 note of the Banco Comercial de Chihuahua has a vignette of Columbus and a native woman, in a secondary place on front right, after a portrait of Hidalgo, and represents a truly Hispanic motif. The original version of this vignette was engraved by Charles Burt in 1868. Based on the avatar for the Americas of the allegories of the four continents, the indigenous woman personifies America, while Columbus signifies Europe in general and Spain in particular. Together, they signal the meeting of the New and Old Worlds with America volunteering Spain her resources, a very kindly take on a violent imperial encounter. Building on a tradition of these paired figures, the vignette is modeled after two statues by Revelli in Lima and Genoa, and was likely developed from available photos and/or lithos of the sculptures.

The same vignette was employed on a total of nine notes from Spain throughout Latin America, from 1872 to 1898. Always on the front and in primary or secondary, it was generally used on high- denomination notes, elevating its value. A second version with a ship at left and Spanish arms right, was engraved by Charlton in 1875 for a Spanish note, while other bills utilized either the original variant or variations on the Spanish vignette, adding or subtracting national emblems. The Mexican application was the last on paper money, perhaps capitalizing on the image’s widespread use and standing.

The vignette enjoyed a long lifespan, some 30 years on notes, and resuscitated again in the 1970s on a Spanish stock certificate. It also inspired other derivative imagery, from tobacco labels to a Dominican Republic stamp.

Acknowledgements

I owe a great debt to a number of people for their crucial encouragement and material support in the development of this presentation: as always, my wife Beth Ekelman who endures my endless investigative adventures; Cory Frampton and the USMexNA for putting together the Convention platform every year, and Liliana Feinburg, Olianna Zelles, and the late Arthur Morowitz of the Champion Stamp Company for their friendship and generous access to the imagery I study.