The signatories on the Banco Comercial notes were Miguel Ahumada as Interventor, Tomás MacManus and Enrique Creel as President, Ignacio MacManus as Director and José María Falomir as Manager (Gerente). Signatures were originally engraved on the plates, but in 1897 when the higher values were altered from 'en moneda de plata del cuño mexicano’' to 'a la par, en efectivo’' the title 'Director' was changed to 'Gerente' and the signatures removed except for the $5 note which had the engraved signatures of Creel and Falomir.

|

Miguel Ahumada Sauceda was born in Colima on 29 September 1844. In his youth he worked as a carpenter and in customs inspection. He fought against the Imperialist government of Emperor Maximilian, initially under the command of General Ramón Corona and then under Sóstenes Rocha. He was a political prefect in 1875-1876, and a local deputy and Jefe de Armas in Colima in 1876. He subsequently was assigned to the Naval Customs Station in Guaymas, Sonora. Ahumada was in charge of the tax service (Jefe de la Gendarmería Fiscal) in Chihuahua in 1892 when Díaz chose him as the compromise candidate for the governorship to settle the political infighting between the Terrazas and Carrillo cliques. He was governor from 1892 until 1904 though he renounced the post in 1903 when he was elected governor of Jalisco, winning reelection until January 1911. During the Maderista revolt in 1911, Díaz once again called upon him to take over the governorship of Chihuahua but this time his influence and prestige were unable to deflect the revolution and he handed over the reins to Abraham González on 10 June. In 1913, he was a deputy in the 9th district of Jalisco in the legislative chamber called up by President Huerta. He was the President of the Chamber of Deputies in 1914. Ahumada was Interventor from at least December 1890 until May 1900 when the bank merged with the Banco Minero. |

|

|

Born on 16 May 1854, young Tomás spent his early life in Mexico along with his sister, Francisca, and his brothers, Ignacio and Francisco but in early 1864 was sent to board at St. John’s College, New York City. Returning home to Mexico after his years there, he joined the family business and found himself involved in real estate, international trade, mining and banking. Tomás Macmanus would become a prominent financial figure, not only in Mexico, but in the US and overseas in Europe as well. Later in his career, Macmanus would become involved with the booming North American railroad industry and would also turn to law and politics, holding various local offices and eventually serving as a state deputy, deputy to Congress, and senator for Chihuahua. He was a business associate of the Terrazas: for example, he was a shareholder in the surveying company, the Compañía deslindadora del Campo y Guerrero y socios, where the manager was Enrique Creel and another shareholder was Juan Terrazas{footnote}The law of 15 December 1883 for the survey and colonisation of uncultivated land (terrenos baldíos) authorised the government to contract with surveying companies to locate and measure terrenos baldíos and to give them in recompense a third of the lands which they surveyed. Whilst the companies were not permitted to dispose of the lands they acquired in blocks greater than 2,500 hectares (6,177 acres) this limit was evaded by the use of dummy companies. Tomás Macmanus was a state deputy when the concession was given to the Compañía deslindadora del Campo y Guerrero y socios in 1883{/footnote}. However, he made a bad decision and lost his fortune during the 1890s as on 8 October 1895 his estates were sold at public auction to satisfy a mortgage held by the Banco de Londres y México{footnote}The Two Republics, Vol. XLI, No. 62, 11 September 1895; Chihuahua Enterprise, 30 August 1895. The estate included the Hacienda de la Nariz, (over)valued at $280,000, its anexas ($70,000), the Hacienda de Bachimba ($57,000) and various houses in the city. Macmanus’ business, Concurso F. Macmanus é hijos, suspended payments to its creditors on 11 April 1893 (Periódico Oficial, 30 May 1896). On 9 May 1896 the Juez 2º de Letras announced that the sale of the goods of Francisco Macmanus Sucesores had raised $71,905.17 (Periódico Oficial, 9 May 1896) and on 26 May 1896, paid a 10% distribution to creditors (Periódico Oficial, 30 May 1896){/footnote}. In later years he was solicitor acting for the Greene Gold Silver Company (in 1905), the Cananea Consolidated Copper Company (in 1906), the Sierra Madre and Pacific Railroad Company (in September 1908) and the Parral and Durango Railroad (in 1913). He took part in the negotiations over Madero’s renunciation and after Huerta’s coup d'etat remained as senator for Querétaro and helped arrange Huerta’s loans from English banks. He died in Cuernavaca on 18 September 1945. |

|

|

Creel was born in Chihuahua on 31 October 1854, the son of merchant Reuben Waggener Creel, who had come to Mexico from Kentucky in 1845, and Paz Cuilty de Creel, one of General Luis Terrazas' sisters{footnote}Reuben W. Creel was born 1815 in Green County, Kentucky. Reuben grew up on a large tobacco plantation in the Green River area that had been established by his father. He was educated at the little Jesuit college of St. Mary's near Bardstown. His instructor in the languages was Louis Phillippe of France, who later returned to France to reign as King. According to a newspaper account, "he was very fond of the languages and was as well versed in Spanish and French as in his mother tongue, English." Reuben went to Mexico as an interpreter for Gen. William T. Ward, husband of Sally Tobin Creel, during the Mexican War in 1847. After the war he returned home, and later was appointed American Consul to Mexico on 12 August 1863 in Chihuahua. It was in his capacity as consultant that Reuben met General Luis Terrazas, who at the time was Governor of Chihuahua. Reuben and Terrazas married sisters, Maria de la Paz Cuilty and Carolina Cuilty Bustamante, Reuben marrying on 8 July 1853 in Chihuahua. The Cuiltys were among the largest landowners in the state. Reuben's first son was named after Henry Clay, the American statesmen he admired the most. Reuben was U.S. consul in Chihuahua during the French intervention.{/footnote}. In his teens Enrique sold cigars and cigarettes on the streets and taught night school. His family's financial difficulties ended his formal education, but his mother, a schoolteacher, undertook his training at home. At fourteen, Enrique managed a small store for his father; after Reuben died in 1871, the seventeen-year-old Creel borrowed three hundred pesos and went into business himself. By the time he was twenty-five, he had "one of the best mercantile houses in Chihuahua."{footnote} J. Adolphus Owens, Anywhere I Wander I Find Facts and Legends Relating to the Creel Family, Alabama, 1975: Chihuahua Mail, 17 October 1882{/footnote}. In 1880 he married Angela Terrazas, the daughter of Luis Terrazas. Through his family connections, vast personal wealth and astute business sense Creel was a prominent member of the oligarchy that came to dominate Chihuahuan industry, politics and the courts. He was elected regidor of Chihuahua in 1878. He was a deputy in several legislatures and at times represented Chihuahua and Durango. He substituted for his uncle, Luis Terrazas, as governor from August 1904 to December 1906, when he went to Washington as Mexican ambassador. He was state governor from October 1907 until 1911 and at times also minister of foreign relations. Creel began his banking activities in 1881 as manager of the branch of the Banco Minero in El Paso del Norte (now Ciudad Juárez) and ended up as President of the bank. As manager of the Terrazas family's banks, he ruled over an empire that counted more than two hundred million pesos in assets, almost a fifth of the nation's total bank assets in 1910. As well as his interests in Chihuahua, he presided over or had substantial interests in banks in Mexico City, Nuevo León, Durango, Guanajuato, Sonora, and the United States{footnote}He was associated with the Sonoran elite as president of the Banco Mercantil de Cananea (Mexican Herald, 22 January 1906, and Mexican Investor, 3 February 1906); in partnership with Joaquin Casasús and several Monterrey entrepreneurs, he founded the Banco Mercantil de Monterrey in 1889; he was also a large stockholder in the Banco Oriental de México and a board member of the Banco de Guanajuato{/footnote}. His most ambitious projects were two large banks in Mexico City. Creel founded the Banco Central Mexicano in 1899 to provide "a mechanism in Mexico City" for state banks of issue to circumvent the currency monopoly of the Banco Nacional. By 1910 it had become Mexico's second largest bank, with assets of ninety million pesos. He also set up the Banco Hipotecario de Crédito Territorial Mexicano, which had thirty-eight million pesos in assets in 1910, to furnish long-term, low-rate mortgages to finance the modernization of agricultural properties. Thus Creel played a crucial role in coordinating native and foreign banking interests. After 1900, as the Mexican member of important international financial committees, he established a worldwide reputation. In matters of national monetary policy, Creel ranked in importance second only to José Ynes Limantour, Diaz's minister of finance, and he was instrumental in formulating many of the fiscal policies of the dictatorship{footnote}He was president of the Comisión de Cambios that planned the monetary reforms of 1905{/footnote}. He travelled widely on behalf of the government and was well-known in financial circles in New York and Paris. After Huerta's defeat and exile, Enrique Creel was one of those who journeyed to Spain in 1915 to persuade the general to return, and thereafter worked with other exiles to circumvent the revolution. Creel never fully won the trust of his nationalistic Mexican compatriots. As his critic Bulnes put it, Creel was 'half yankee by blood' and 'by character and education a yankee-and-a-half'. He died on 17 August 1931 in Mexico City. |

|

|

He died on 22 November 1932 in Glendale, California. |

|

|

José María Falomir Gastelum was born in Yecorato in the district of El Fuerte, Sinaloa on 2 December 1827. The Falomirs were political allies of the Terrazas with large landholdings around the city of Chihuahua, in Aldama and in Ciudad Jiménez. José María served as a deputy to the local legislature. José María married three times and had 14 children. From his first marriage he had a son, Ponciano Falomir Casares, From his second a daughter, Mariana Falomir Albiztegui, married Pedro Olivares Zuloaga in 1883. Fom his third Falomir had sons, Martín and Jesús José Falomir Caballero, and a a daughter, Josefina Falomir Caballero, who also married Pedro Olivares Zuloaga (in 1897). Falomir was manager between April 1894 and April 1900 though in 1895 and 1896 his office was frequently covered by Luis Rosas or Ponciano Falomir. He died in Chihuahua on 11 May 1900{footnote}La Patria, 17 May 1900{/footnote}, at the age of 72. |

|

Other people associated with the bank were:

| J. Allard was cajero in December 1891 and contador between April 1892 and 1900, though from 1893 onwards the balance sheets were signed on his behalf by the cajero Augusto G. Lowere. | |

| Juan Andrew Creel was born in Chihuahua in 1865, the brother of Enrique Creel. He went on to be manager of the Banco Minero. | |

| Jesús José Falomir was assistant manager (subgerente) in May 1900 and later worked in the Banco Minero. Born in Chihuahua on 25 December 1873, like Martín Falomir, he also married into the family of José María Maytorena of Sonora, marrying the daughter Armida Maytorena Tapia. He died in Chihuahua on 8 September 1935. | |

| Ponciano Falomir Casares, a half-brother of Martín Falomir, was born in Chihuahua on 19 November 1847. A businessman in Santa Eulalia, he owned 270,000 acres of land. He covered for his father, José María Falomir, as manager between July and October 1896. He died in Mexico City on 14 October 1917. | |

|

Adolph Krakauer was manager of the Ciudad Juárez branch in March 1888. Adolph Krakauer was born in Fürth, Bavaria, on 23 May 1846 and emigrated to New York in 1865 and was employed as a clerk there. In 1869 he moved to San Antonio, Texas, where he went to work for Louis Zork, a leading merchant. He married Zork's daughter Ada and became a member of the firm. In 1875 he moved to El Paso, where in 1885, with his brother Máximo, brother-in-law Gustave Zork and Ed Moye, he opened a hardware store on South El Paso Street. The company became a leading wholesale hardware dealer in the Southwest, with a branch in Chihuahua. Krakauer also became president of Two Republic Life Insurance Company, the Krakauer-Zork Investment Company, and the Mountainside Realty Company and director of the First National Bank and the Rio Grande Valley Banking and Trust Company. He also owned extensive real estate in El Paso. He served as county commissioner and alderman and was elected mayor as a Republican after a bitter election campaign in 1889 but never assumed the office, as it was discovered he had not taken out his final citizenship papers. He died of a heart attack in El Paso on 22 January 1914, and was survived by three children{footnote}El Paso Herald, 22 January 1914{/footnote}. Krakauer, Zork y Moye opened in Chihuahua in 1890 . Their hardware store stood in front of the Cathedral on calle Libertad and calle Segunda and sold all sorts of hardware and, most importantly, dynamite in 50 pound boxes (stored offsite on the outskirts of the city). |

|

| Máximo Krakauer was on the board in March 1888. He had two sons, Julio and Adolfo, the last of whom took care of the hardware from the 1920s until 1948, when the business was sold. Maximo Krakauer died in El Paso in 1930, at the age of 65 years. | |

| Ralph L. O'Neill was the nephew of Francisco MacManus and in charge of the hacienda at Bachimba in 1880{footnote}Grant Shepherd, The Silver Magnet, New York, 1938{/footnote}. He was contador from at least December 1890 until April 1892. He must have followed Ignacio MacManus to Cananea as in 1906 he was manager of the Compañía Bancaria Mercantil de Cananea, the banking business of the Cananea Consolidated Copper Company. In 1913 The Oasis reported, 'Mr. R. L. O’Neill, the Cashier, has had thirty years experience in banking and commercial businesses in the Southwest, upon both sides of the international line, in Arizona and Texas, and in Sonora, Chihuahua and Durango; and he is in complete and thorough touch with all the great and varied interests of all that vast region of illimitable resources, which gives the institution under his management a great advantage in dealing with men and conditions'{footnote}The Oasis, 25 December 1913{/footnote}. | |

| Carlos Pérez: | |

| Luis Rosas frequently covered for José María Falomir as manager in 1895 and 1896. | |

| Alberto Terrazas was the son of Luis Terrazas, born in September 1869. In 1910 Díaz felt he need to bind the Terrazas more closely to his rule and in December chose Alberto as governor of Chihuahua to replace Creel and Terrazas’ creature, José María Sánchez. However, Alberto was unable to stave off the rebellion and was replaced by the firmer pair of hands of Miguel Ahumada in January 1911. He was driven out of Chihuahua in 1914 but returned after the revolution in 1920. He was married to Emilia Creel, Enrique's daughter and his own niece. He died in El Paso in 1926. | |

| Federico Terrazas was another son of Luis Terrazas. | |

| Juan Terrazas Cuilty was a son of Luis Terrazas and a vocal on the board of directors. Born in the city of Chihuahua in 1852, as a member of the family he owned vast estates, had interests in several companies, including as Tesorero of the Batopilas Mining Company, and a distinguished political career, including local deputy and senator for Campeche. In 1878 he established a general store, 'Juan Terrazas', at calle Juárez 601, Chihuahua. He was President of the Cámara de Comercio, Industrial, Agrícola y Minera de Chihuahua in 1900, 1902, 1909 and 1910. He died in Chihuahua in 1925. |

|

| Luis Terrazas was on the board. | |

| Luis Terrazas, hijo was on the board in 1888 | |

| [ ] Von Düring appears in the balance sheets as manager from April 1893 until March 1894. |

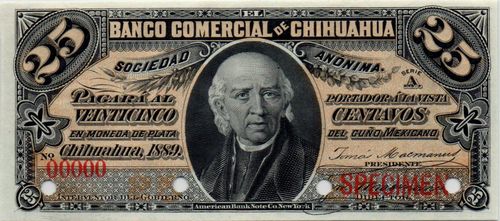

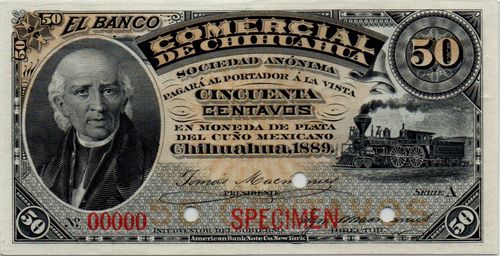

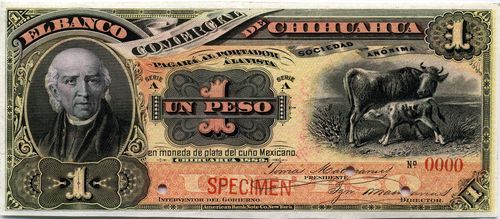

The American Bank Note Company produced its first notes on an original order of 18 March 1890{footnote}The following plates were made

One 25c face and back plate (each of 12 notes) and one 25c tint plate.

One 50c face and back plate (each of 12 notes) and one 50c tint plate (No. 2).

One $1 face and back plate (each of 10 notes) and two $1 tint plates (No. 1 and 2).

One $5 face and back plate (each of 4 notes) and two $1 tint plates (No. 1 and 2).

One $10 face and back plate (each of 2 notes) and two $1 tint plates (No. 1 and 2).

One $20 face and back plate (each of 2 notes) and two $1 tint plates (No. 1 and 2).

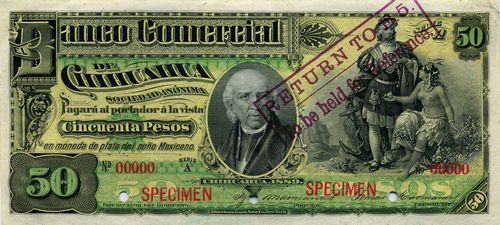

One $50 face and back plate (each of 1 note) and two $1 tint plates (No. 1 and 2).

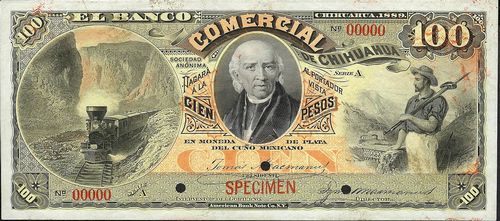

One $100 face and back plate (each of 1 note) and two $1 tint plates (No. 1 and 2).

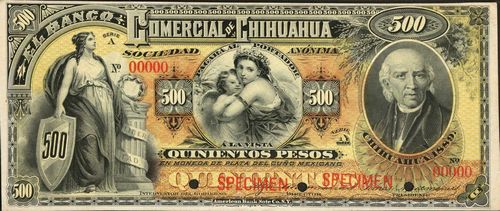

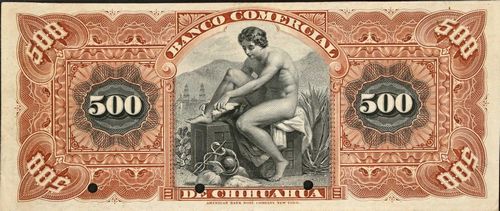

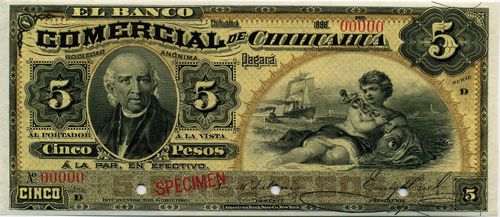

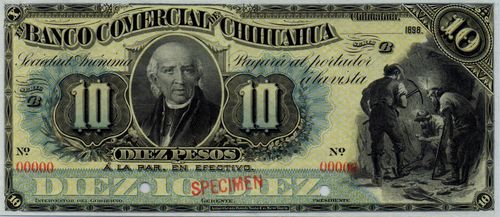

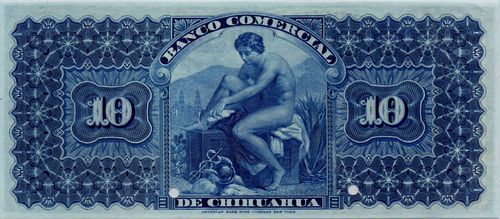

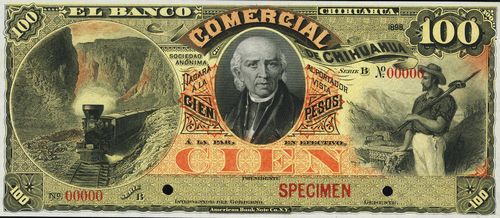

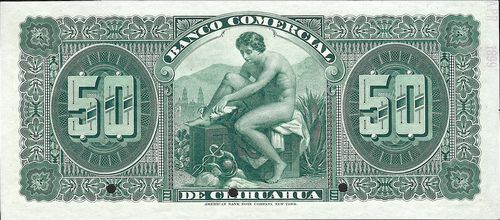

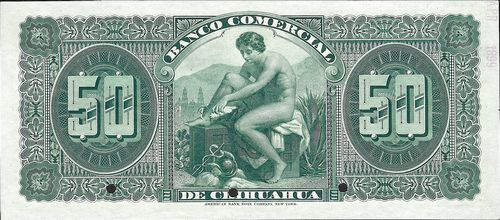

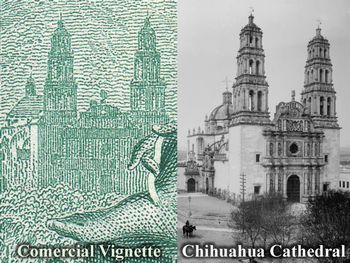

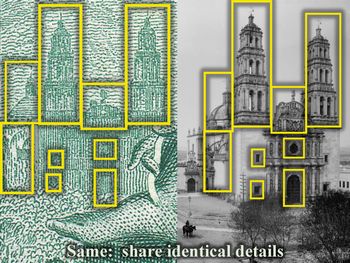

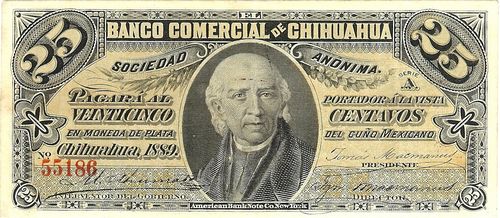

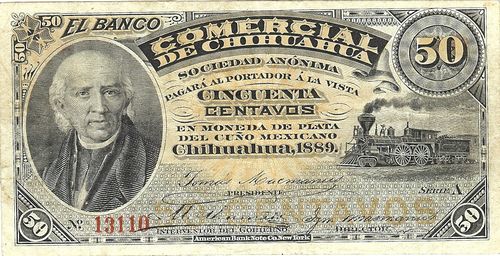

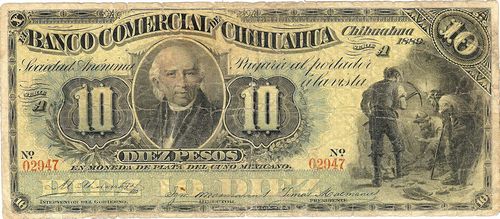

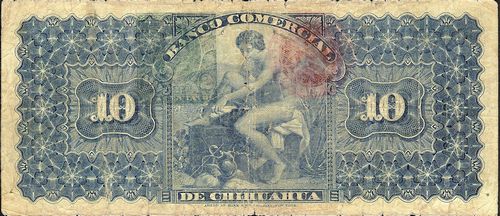

One $500 face plate, one centre back plate and one border back plate (each of 1 note) and two $500 tint plates (No. 1 and 2). (ABNC, folder 1525, Banco Comercial de Chihuahua (1931-1932)){/footnote}. The ABNC engraved a special vignette portrait of Miguel Hidalgo (C 172) which appears on the face of all denominations. It also produced an allegory of Commerce (the god Mercury sitting on a cashbox and flanked by Mexican motifs and the Cathedral in Chihuahua) for the reverse of the higher denominations from $5 up.

In addition, the 25c has a vignette of one of Rafael’s putti from his Madonna in the Sistine Chapel on the reverse.

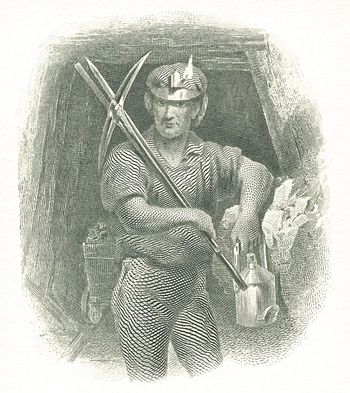

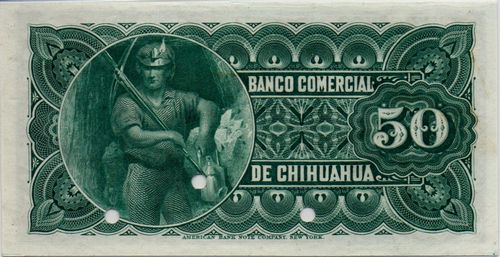

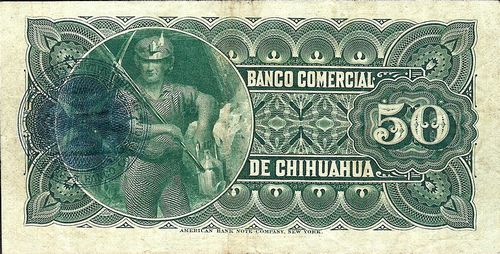

The 50c has a train on the face and a miner on the reverse.

The $1 has a vignette of a cow with her calf on the face and a vignette of a muleteer with a string of pack mules on the reverse. The latter came from the National Bank Note Company’s stock of vignettes and had previously been used on the $1 Banco de Chihuahua.

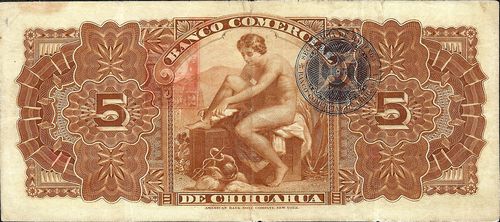

The $5 has a vignette of a young Mercury with a caduceus astride an unhappy-looking dolphin in front of shipping on the face and Mercury on the reverse.

The $10 has a group of miners on the face, and Mercury on the reverse.

The $20 has a pastoral scene with a flock of sheep and a vignette of an Indian woman on the face, and Mercury on the reverse.

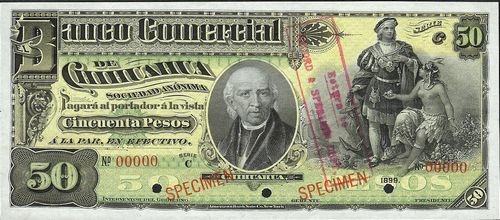

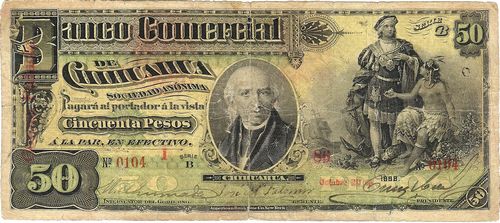

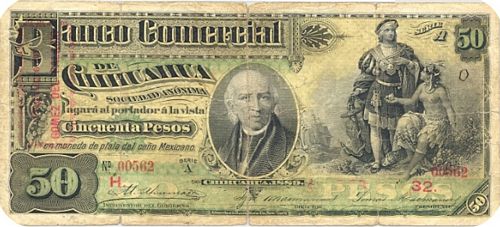

The $50 has a vignette of Christopher Columbus, which is the subject of this article by Peter Dunham.

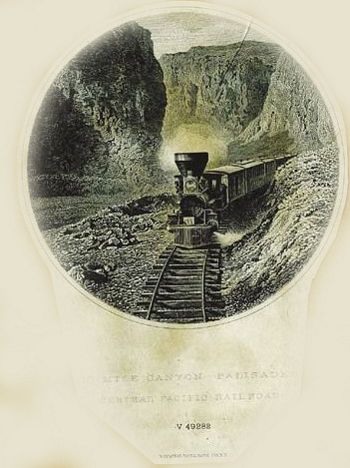

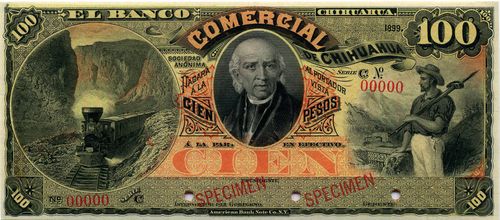

The $100 has two additional vignettes on the face. The vignette of a locomotive was from the stock of the National Banknote Company and was entitled "10 Mile Canyon Palisades - Central Pacific Railroad", later numbered V-49282. The other vignette is of a miner(?) looking down on a train.

The $500 is particularly infelicitous with Liberty holding a shield on the left, and a woman and child, the "Protector of Cherubs", in the centre.

| Date | Value | Number | Series | from | to |

| March 1890 | 25c | 80,000 |

A | 1 | 80000 |

| 50c | 60,000 |

A | 1 | 60000 | |

| $1 | 50,000 |

A | 1 | 50000 | |

| $5 | 20,000 | A | 1 | 20000 | |

| $10 | 15,000 | A | 1 | 15000 | |

| $20 | 7,500 | A | 1 | 7500 | |

| $50 | 4,000 | A | 1 | 4000 | |

| $100 | 2,000 | A | 1 | 2000 | |

| $500 | 400 | A | 1 | 400 |

| Date | Value | Number | Series | from | to |

| September 1891 | $1 | 50,000 |

A | 50001 | 100000 |

In October 1897 the series was changed to B, dateline was altered to read "Chihuahua, ______1898", and "en Moneda de Plata del cuño Mexicano" was changed to "a la par en efectivo". All the signatures were erased and "Director" changed to "Gerente". As the government had just allowed facsimile signatures on low value notes (circular núm. 3) Enrique Creel and José M. Falomir's signatures were engraved on the $5 plate.

In November 1897 the ABNC made a new $5 face plate (of 4 notes).

| Date | Value | Number | Series | from | to |

| October 1897 | $5 | 60,000 |

B | 1 | 20000 |

| C | 1 | 20000 | |||

| D | 1 | 20000 | |||

| $10 | 5,000 |

B | 1 | 5000 | |

| $20 | 5,000 | B | 1 | 5000 | |

| $50 | 1,000 | B | 1 | 1000 | |

| $100 | 1,000 |

B | 1 | 1000 |

In March 1899 the date and series letter were changed to 1899 and C.

| Date | Value | Number | Series | from | to |

| March 1899 | $10 | 5,000 |

C | 1 | 5000 |

| $20 | 5,000 |

C | 1 | 5000 | |

| $50 | 1,000 | C | 1 | 1000 | |

| $100 | 1,000 | C | 1 | 1000 |

The American Bank Note Company archives produce additional facts. Amongst the specimens there were two different background colours for the 1889 $1 note{footnote}The 1890 specimen has [ ], the July 1890 specimen has a diffused pink background whilst the September 1891 specimen has a lighter background{/footnote}, an 1898 $5 Series D (approved in January 1898 and so not printed) and an 1898 $50 Series C.

On 27 October 1931 Roberto Casas Alastriste, of the Comité liquidador de los Antiguos Bancos de Emisión, gave the American Bank Note Company permission to cancel the plates and these were cancelled on 18 February 1932{footnote}ABNC, folder 1525, Banco Comercial de Chihuahua (1931-1932){/footnote}.

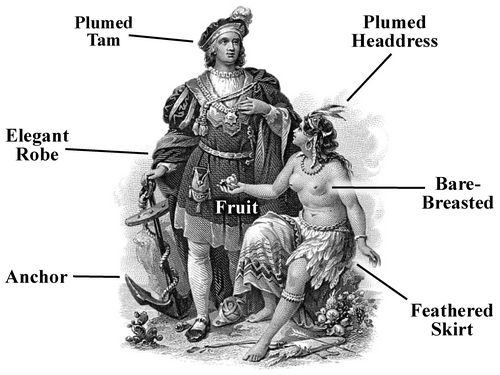

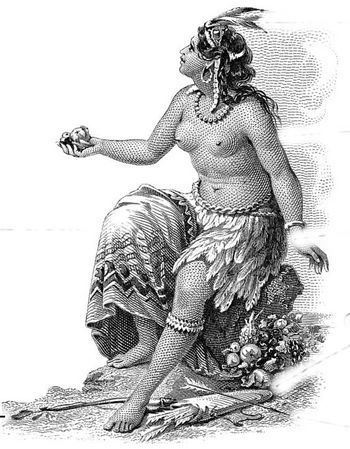

In this article I explore the significance of the American Bank Note Company (“ABNC”) vignette of Columbus and a Native American woman initially engraved by Charles Burt in 1868. The original, basic version is distinguished by the elegantly robed Columbus standing at left, staring distantly, sporting a tam with plume, his right hand resting on an anchor to the left, an astrolabe and chart at his feet. Offering him a handful of fruit, the semi nude native woman sits at his side to the right, gazing up at him, wearing a plumed headdress, jewellery, and feathered skirt, a blanket draped on her right knee, quiver, bow, arrow, and bunch of fruit at her feet. The die proof is labeled “Columbus,” confirming the explorer’s identity.

In this article I explore the significance of the American Bank Note Company (“ABNC”) vignette of Columbus and a Native American woman initially engraved by Charles Burt in 1868. The original, basic version is distinguished by the elegantly robed Columbus standing at left, staring distantly, sporting a tam with plume, his right hand resting on an anchor to the left, an astrolabe and chart at his feet. Offering him a handful of fruit, the semi nude native woman sits at his side to the right, gazing up at him, wearing a plumed headdress, jewellery, and feathered skirt, a blanket draped on her right knee, quiver, bow, arrow, and bunch of fruit at her feet. The die proof is labeled “Columbus,” confirming the explorer’s identity.

I employ two fairly straightforward concepts in my analyses of imagery on paper money:

1. “Visual Linguistics” – I read Mexican banknotes like Western texts, from front to back, left to right, and top to bottom, with the images accented by size, position, or framing, establishing an order and even a hierarchy of symbols.

2. The “Imaginario” – a group of images, visual, textual, or verbal, arranged to project a desired association, similar to how a photo mosaic or photo array on social media evokes an overarching theme.

The Banco Comercial de Chihuahua 50 pesos has three vignettes, two on the front and one on the back. On the front a portrait of Hidalgo, hero of independence, is in the lead position, first from left at center, in a scrolled frame captioned “Chihuahua,” where Hidalgo died, while the Columbus-native woman vignette is secondary, at front right without a frame but considerably larger than Hidalgo. A large allegory of Commerce (the god Mercury with his winged helmet, sandals, and caduceus sitting on a cash box) framed by the bank’s name (Comercial) is tertiary at back center. Mercury is flanked by Mexican motifs: a nopal cactus. maguey and the Cathedral in Chihuahua (based on Henry William Jackson’s photograph).

Returning to our focal vignette, the native woman symbolizes America or the Americas. With her plumed headdress, bow, arrow, quiver, feathered skirt, cape, and bare torso, she reprises the widely embraced avatar of the Americas from the four continent allegories formalized by Ripa in 1603. The same icon was broadly employed to signify America and even the US in paper money vignettes from the 1800s and she was also adapted to embody a number of American countries on medals and coins, as I have shown in my article “Native Identity and Independence on the Chihuahua Coppers of the First Republic”.

Returning to our focal vignette, the native woman symbolizes America or the Americas. With her plumed headdress, bow, arrow, quiver, feathered skirt, cape, and bare torso, she reprises the widely embraced avatar of the Americas from the four continent allegories formalized by Ripa in 1603. The same icon was broadly employed to signify America and even the US in paper money vignettes from the 1800s and she was also adapted to embody a number of American countries on medals and coins, as I have shown in my article “Native Identity and Independence on the Chihuahua Coppers of the First Republic”.

With the Native American woman signifying America, what would Columbus represent? In keeping with her example as a continental allegory, he undoubtedly personifies Europe in general. Sailing under the Spanish flag as a native of Genoa, Italy, he also stands for Spain in particular and perhaps even Italy.

With the Native American woman signifying America, what would Columbus represent? In keeping with her example as a continental allegory, he undoubtedly personifies Europe in general. Sailing under the Spanish flag as a native of Genoa, Italy, he also stands for Spain in particular and perhaps even Italy.

Together the figures signal the encounter between the “Old” and “New Worlds”, but as America presents her fruits (resources) to Europe/Spain, his gaze is fixed beyond her as if he is looking for more than just fruit.

The Columbus-America vignette builds on a long artistic history of pairing such figures. For example, Galle’s engraving of c1600 features a Columbus-like Amerigo Vespucci standing before America seated on a hammock, Persico’s 1844 statue, formerly at the east portico of the U.S. Capitol, has a triumphant Columbus looming over a cowering America stripped nearly naked, whilst Vela’s bronze in Colón, Panamá, which debuted at the 1867 Paris Exposition, presents a towering Columbus comforting a traumatized America.

However, the ABNC vignette draws directly from two monumental sculptures in Lima, Peru and Genoa, Italy, both designed by Salvatore Revelli:

• they share the same composition as the vignette but reversed; it was probably engraved as seen and flipped when printed;

• the 1860 statue in Lima clothes a standing Columbus in tam and finery nearly identical to the vignette and equips a seated America with her arrow and quiver, looking up at Columbus, like the vignette,

• the 1862 marble in Genoa introduces the anchor to Columbus and fruit to America.

With vignette artists unlikely to visit far-off statues, photos and engravings predating the 1868 vignette were probably used as models:

• Lima – Courret released a promising photo (1860s) and Semino published a litho (1855) in Michelangelo, both sharing the same aspect as the vignette.

• Lima – Courret released a promising photo (1860s) and Semino published a litho (1855) in Michelangelo, both sharing the same aspect as the vignette.

• Genoa – there were multiple images, a number comparable in aspect to the vignette, like Sommer’s stereoview (c1862-66) and the woodcut (1850s) in Leipziger Ilustrierte Zeitung.

• Genoa – there were multiple images, a number comparable in aspect to the vignette, like Sommer’s stereoview (c1862-66) and the woodcut (1850s) in Leipziger Ilustrierte Zeitung.

• Colón – the Michelez photo from the 1867 Paris Expo and the Blanadet-Jonnaro woodcut (1867) in L’universo illusrato again offer aspects similar to the vignette

• U.S. Capitol – the Bell stereoview (1867) and Best-Leloir woodcut (1845) in Le magasin pittoresque provide helpful likenesses.

The Columbus-America vignette was used on banknotes of nine countries in mainland Spain and throughout the Americas, including Mexico. In all cases the vignette is either primary or secondary, always on the front, and when secondary, it is usually accentuated by being larger and/or in a frame.

The associated notes are generally among the highest denominations in their series, placing an elevated value on the image and these high values also fostered its circulation among wealthier users and commercial institutions, such as banks.

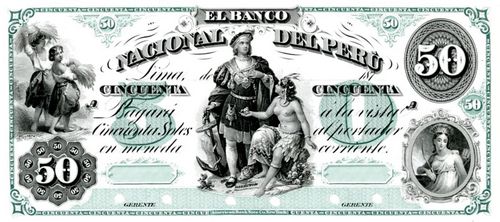

The vignette varied among applications, the initial variety (V-47313 591) being the basic one, Columbus and Native America alone, sans elaboration. Engraved by Burt in 1868, it was fi rst used on the Peruvian bill (50 pesos, El Banco Nacional del Peru) in 1872, four years later. This was not likely a custom order but probably also not random, either, as a main source image from which it was modeled, the Lima statue, is in Peru.

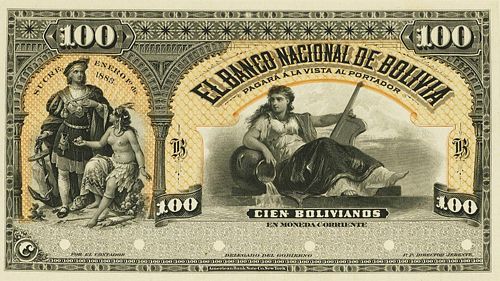

The vignette was heavily utilized. It also appeared on Colombian (100 pesos, Banco de Marquez, c1882), Bolivian (100 bolivianos, El Banco Nacional de Bolivia, c1883), and Venezuelan notes (100 pesos, Banco Comercial, c886), four of the full complement of nine (44%).

The original 50 pesos, El Banco Nacional del Peru

100 bolivianos, El Banco Nacional de Bolivia

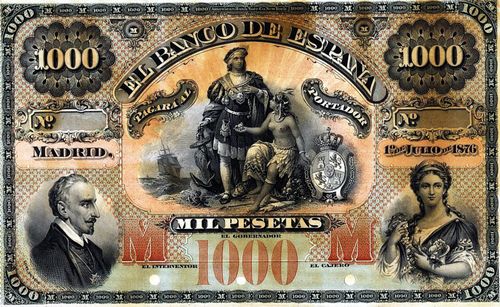

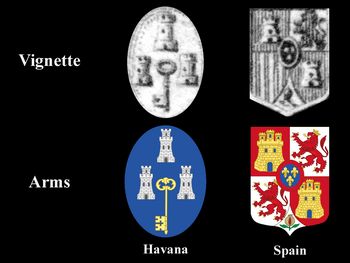

1,000 pesetas, El Banco de España

A second version of the vignette (V-47149 772) was developed for the Spanish note (1,000 pesetas, El Banco de España, 1876); engraved by William Charlton in 1875, it was “Spanishized”. A (Spanish?) sailing ship was added at left, at right the royal coat of arms of the Spanish monarchy from 1700 to 1931; the Spanish arms appropriate the scene for Spain and tag Columbus as the personification of Spain, not just of Europe and in the title “Reception of Columbus” the die proof hints that the Americas welcomed the Old World (Spain), painting imperialism in a sympathetic light.

A second version of the vignette (V-47149 772) was developed for the Spanish note (1,000 pesetas, El Banco de España, 1876); engraved by William Charlton in 1875, it was “Spanishized”. A (Spanish?) sailing ship was added at left, at right the royal coat of arms of the Spanish monarchy from 1700 to 1931; the Spanish arms appropriate the scene for Spain and tag Columbus as the personification of Spain, not just of Europe and in the title “Reception of Columbus” the die proof hints that the Americas welcomed the Old World (Spain), painting imperialism in a sympathetic light.

100 pesos, Banco de España y Rio de la Plata

50 centavos, El Banco Español de la Habana

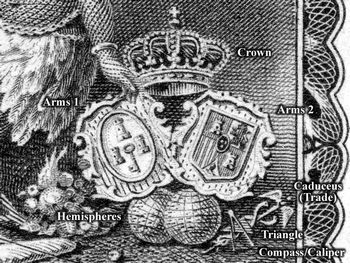

Other varieties are adaptations of the Spanish version, plus or minus national insignia The Dominican Republic (50 pesos, El Banco de la Compañía de Crédito de Puerto Plata, c1886) and Mexican bills employ the Spanish vignette but with the Spanish arms supplanted by vegetation at right; the Uruguayan (100 pesos, Banco de España y Rio de la Plata, 1888) note, issued by a joint Spanish-Argentine bank, maintains the Spanish arms at right but replaces the ship with the Argentine arms at left, whilst the Cuban bill (50 centavos, El Banco Español de la Habana, 1889) adds the arms of Habana to the Spanish arms at right, above two hemispheres, navigational aids, and a caduceus for commerce, all below a crown.

As vignettes go, this Columbus-America motif had a fairly long span of use and currency. Following its creation by Burt in 1868, its fi rst use on a banknote was in 1872 on the Peruvian note; it was utilized most heavily during the 1880s on six bills throughout Latin America, and its last appearance on a banknote was in 1898 on the Mexican note, 30 years after its original creation. It was resurrected as late as the 1970s on a stock certificate for Telefónica de España, over a century after its initial formulation.

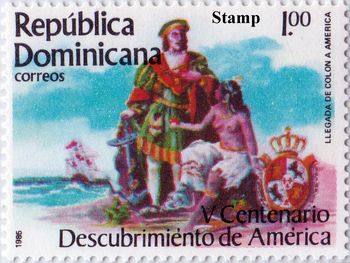

It also inspired a series of images in other media. Several brands of cigars produced for the World Fair of the Columbian quadricennial of 1893 in Chicago bore images on their labels that were based on it, where a native woman sits on right gazing up at and handing tobacco leaves to an elegant Columbus standing in center with anchor, backed by ship(s) at left. For the Columbian quincentenary, in 1985, the Dominican Republic released a postal stamp with a color version of the vignette.

The 50 note of the Banco Comercial de Chihuahua has a vignette of Columbus and a native woman, in a secondary place on front right, after a portrait of Hidalgo, and represents a truly Hispanic motif. The original version of this vignette was engraved by Charles Burt in 1868. Based on the avatar for the Americas of the allegories of the four continents, the indigenous woman personifies America, while Columbus signifies Europe in general and Spain in particular. Together, they signal the meeting of the New and Old Worlds with America volunteering Spain her resources, a very kindly take on a violent imperial encounter. Building on a tradition of these paired figures, the vignette is modeled after two statues by Revelli in Lima and Genoa, and was likely developed from available photos and/or lithos of the sculptures.

The same vignette was employed on a total of nine notes from Spain throughout Latin America, from 1872 to 1898. Always on the front and in primary or secondary, it was generally used on high- denomination notes, elevating its value. A second version with a ship at left and Spanish arms right, was engraved by Charlton in 1875 for a Spanish note, while other bills utilized either the original variant or variations on the Spanish vignette, adding or subtracting national emblems. The Mexican application was the last on paper money, perhaps capitalizing on the image’s widespread use and standing.

The vignette enjoyed a long lifespan, some 30 years on notes, and resuscitated again in the 1970s on a Spanish stock certificate. It also inspired other derivative imagery, from tobacco labels to a Dominican Republic stamp.

I owe a great debt to a number of people for their crucial encouragement and material support in the development of this presentation: as always, my wife Beth Ekelman who endures my endless investigative adventures; Cory Frampton and the USMexNA for putting together the Convention platform every year, and Liliana Feinburg, Olianna Zelles, and the late Arthur Morowitz of the Champion Stamp Company for their friendship and generous access to the imagery I study.

| Date of issue | Date on note | Series | from | to | Interventor | Presidente | Director | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1889 | A | 00001 | 80000 | Ahumada | T.MacManus | I.MacManus | includes up to number 79487{footnote}CNBanxico #9990{/footnote} |

| Date of issue | Date on note | Series | from | to | Interventor | Presidente | Director | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1889 | A | 00001 | 60000 | Ahumada | T.MacManus | I.MacManus | includes up to number 58575 |

| Date of issue | Date on note | Series | from | to | Interventor | Presidente | Director | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1890 March | 1889 | A | 00001 | 50000 | Ahumada | T.MacManus | I.MacManus | |

| 1891 September | 50001 | 100000 | includes up to number 71830 |

| Date of issue | Date on note | Series | from | to | Interventor | Presidente | Director | code | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1889 | A | 00001 | 10000 | Ahumada | T.MacManus | I.MacManus | includes numbers 01075 to 03743{footnote}CNBanxico #9993{/footnote} | ||

| 15 August 1897{footnote}alternative: authorised on 7 October 1897{/footnote} | 1897/1889 | 10001 | |||||||

| E 30 | includes number 15991 | ||||||||

| F 86 | includes number 17645 | ||||||||

| 20000 | K 54 | includes number 18218{footnote}CNBanxico #9751{/footnote} | |||||||

| 20 April 1898 | 20 May 1898 | B | 00001 | Ahumada | Creel | Falomir | E 148 | includes number 01989 | |

| L 108 | includes number 02420 overprinted Gomez Palacio (Type 3) | ||||||||

| U 138 | includes number 03434 overprinted GOMEZ PALACIO (Type 3) | ||||||||

| 10000 | C 152 | includes number 09430 overprinted GOMEZ PALACIO | |||||||

| 15 June 1898 | 10001 | E 286 | includes number 12345 overprinted GOMEZ PALACIO (Type 4) | ||||||

| F 201 | includes number 12836 overprinted GOMEZ PALACIO (Type 4) | ||||||||

| 20000 | [ ] 242 | includes number 18775 overprinted GOMEZ PALACIO | |||||||

| C | 00001 | 20000 | might not have been issued | ||||||

| 1898 | D | 00001 | 20000 | might not have been issued |

| Date of issue | Date on note | Series | from | to | Interventor | Presidente | Director | code | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1889 | A | 00001 | 07500 | Ahumada | T.MacManus | I.MacManus | includes numbers 00259{footnote}CNBanxico #26902{/footnote} to 07440{footnote}CNBanxico #9994{/footnote} | ||

| 15 August 1897{footnote}alternative: authorised on 7 October 1897{/footnote} | 07501 | 08500 | |||||||

| 08501 | 15000 | might not have been issued | |||||||

| 20 October 1898 | B | 0001 | Ahumada | Creel | Falomir | X 49 | includes number 0850 overprinted Gomez Palacio (Type 4) | ||

| J 17 | includes number 1052 overprinted GOMEZ PALACIO | ||||||||

| R 51 | includes number 1210 overprinted GOMEZ PALACIO | ||||||||

| 19 August 1899 / 1898 | 4000 | O 71 | includes number 3160{footnote}CNBanxico #188{/footnote} to 3196 overprinted GOMEZ PALACIO (Type 5) | ||||||

| 20 October 1898 | 5000 | ||||||||

| C | 0001 | 5000 | probably not issued |

| Date of issue | Date on note | Series | from | to | Interventor | Presidente | Gerente | code | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1889 | A | 00001 | 07500 | Ahumada | T.MacManus | I.MacManus | includes number 01251 | ||

| 1898 | B | 0001 | 1500 | ||||||

| April 1899{footnote}informe of interventor Ahumada, 29 July 1899 in Memoria de las Instituciones de Crédito correspondiente a los años de 1897, 1898 y 1899{/footnote} | 1501 | 2500 | Ahumada | Creel | Falomir | U 33 | includes number 2373 overprinted Gomez Palacio (Type 1) | ||

| 19 August 1899 / 1898 | 2501 | N 63 | includes numbers 3342 to 3387 overprinted GOMEZ PALACIO | ||||||

| O 87 | includes number 3689 overprinted GOMEZ PALACIO (Type 4) | ||||||||

| S 83 | includes number 4229 overprinted GOMEZ PALACIO (Type 5) | ||||||||

| 5000 | O 67 | includes number 4614 overprinted GOMEZ PALACIO | |||||||

| 1899 | C | 0001 | 5000 | probably not issued |

| Date of issue | Date on note | Series | from | to | Interventor | Presidente | Director | code | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1889 | A | 0001 | Ahumada | T.MacManus | I.MacManus | I 86 | includes number 0101{footnote}CNBanxico #9996{/footnote} overprinted Gomez Palacio (Type 1) | ||

| H 32 | includes numbers 00534 to 00562{footnote}CNBanxico #190{/footnote} overprinted PAGADERO EN GOMEZ DEL PALACIO (Type 2) | ||||||||

| 01000 | E 64 | includes number 00985{footnote}CNBanxico #9995{/footnote} | |||||||

| 01001 | 04000 | might not have been issued | |||||||

| 20 October 1898 | B | 0001 | Ahumada | Creel | Falomir | D 18 | includes numbers 0095 overprinted Gómez Palacio, 'O' | ||

| 0400 | I 86 | includes numbers 0101{footnote}CNBanxico #9996{/footnote} to 0104 overprinted Gómez Palacio, 'O' | |||||||

| April 1899{footnote}informe of interventor Ahumada, 29 July 1899 in Memoria de las Instituciones de Crédito correspondiente a los años de 1897, 1898 y 1899{/footnote} | 1 May 1898 | 0401 | M 31 | includes numbers 0452 to 0477 overprinted GOMEZ PALACIO (Type 6) | |||||

| A 79 | includes number 0504 overprinted GOMEZ PALACIO | ||||||||

| O 99 | includes number 0602 overprinted GOMEZ PALACIO | ||||||||

| T 25 | includes number 835 overprinted GOMEZ PALACIO | ||||||||

| 1000 | X 1 | includes number 0959 overprinted GOMEZ PALACIO | |||||||

| C | 0001 | 1000 | probably not issued |

|

|

Some $50 notes{footnote}known numbers include Series A 00362, 00534, 00562, Series B 0101, 0104, 0452, 0477{/footnote} have a script O above and behind the Indian woman’s right shoulder.

| Date of issue | Date on note | Series | from | to | Interventor | Presidente | Director | code | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1889 | A | 00001 | Ahumada | T.MacManus | I.MacManus | ||||

| 00400 | A 93 | includes number 00363{footnote}CNBanxico #191{/footnote} overprinted Gomez Palacio (Type 1) | |||||||

| 00401 | 02000 | might not have been issued | |||||||

| B | 0001 | 0200 | |||||||

| April 1899{footnote}informe of interventor Ahumada, 29 July 1899 in Memoria de las Instituciones de Crédito correspondiente a los años de 1897, 1898 y 1899{/footnote} | 1 May 1898 | 0201 | 0700 | Ahumada | Creel | Falomir | C 24 | includes number 0647 overprinted GOMEZ PALACIO (Type 5) | |

| 19 August 1899 / 1898 | 701 | 1000 | I 34 | includes number 00812 overprinted GOMEZ PALACIO | |||||

| C | 0001 | 1000 | probably not issued |

| Date of issue | Date on note | Series | from | to | Interventor | Presidente | Director | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1889 | A | 001 | 400 | Ahumada | T.MacManus | I.MacManus |

From 1890 the bank published a brief balance sheet every month in the Periódico Oficial, including the total value of notes in circulation.

| 1890 | 1891 | 1892 | 1893 | 1894 | 1895 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan | 66,178·00 | 193,884·25 | 196,776.50 | 86,424·00 | 136,692·00 | |

| Feb | 97,430·25 | 183,608·25 | 212,840·00 | 75,789.00 | 122,782·00 | |

| Mar | 127,429·00 | 178,651·25 | 196,675·00 | 78,005·50 | 120,595·00 | |

| Apr | 145,307·00 | 164,294·00 | 171,903·38 | 78,821·50 | 127,779·00 | |

| May | 154,863·00 | 183,573·25 | 140,925·13 | 90,649·25 | 138,211·25 | |

| Jun | 161,280·75 | 158,677·25 | 114,346·00 | 83,705.00 | 131,442·50 | |

| Jul | 168,419·25 | 175,168·25 | 111,174·25 | 98,635·00 | 154,080·00 | |

| Aug | 169,595·00 | 173,888·00 | 99,594·00 | 107,294·00 | 145,126·00 | |

| Sep | 179,694·50 | 178,561·50 | 88,078·75 | 109,403·50 | 150,061·00 | |

| Oct | 190,267·00 | 170,134·50 | 91,885·50 | 106,732·25 | 147,333·00 | |

| Nov | 187,064.25 | 194,441·50 | 98,858·00 | 123,114·25 | 158,059·00 | |

| Dec | 35,850·00 | 191,005·50 | 189,586.00 | 89,692·50 | 136,673·25 | 165,688·00 |

| 1896 | 1897 | 1898 | 1899 | 1900 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan | 164,150·00 | 180,991·00 | 270,347·75 | 335,500·00 | 517,105·00 |

| Feb | 152,106.50 | 206,479·00 | 259,458·75 | 380,105·00 | 582,995·00 |

| Mar | 152,217·00 | 206,603·00 | 248,563·25 | 371,237·00 | 578,083·00 |

| Apr | 145,409·00 | 208,644·75 | 269,353·75 | 368,594·00 | 591,940·50 |

| May | 159,818·50 | 205,815·00 | 296,610·75 | 409,197·00 | 562,439·00 |

| Jun | 157,602·00 | 249,475·50 | 286,069·75 | 446,249·00 | 596,098·50 |

| Jul | 166,443·00 | 271,984·50 | 246,281·00 | 450,285·00 | |

| Aug | 171,733·00 | 262,598·00 | 246,125·00 | 453,749·00 | |

| Sep | 176,404·00 | 258,193·00 | 297,341·50 | 453,373·00 | |

| Oct | 179,640·25 | 258,762·00 | 321,312·00 | 440,415·50 | |

| Nov | 181,287·00 | 268,086·00 | 305,518·25 | 447,828·00 | |

| Dec | 185,161.00 | 279,369·75 | 303,502·50 | 469,710·00 |

The new Banco Comercial must always have been overshadowed by the other Terrazas-Creel bank, the Banco Minero, and it can be seen that its own issue of notes was remarkably small. It finally merged with the Banco Minero on 1 July 1900{footnote}El Norte, 1 July 1900. Creel had proposed the merger in February 1900 to increase the Banco Minero’s capital assets.{/footnote} and officials of the latter bank were in charge of the withdrawal of all its notes.

Some notes were withdrawn in the early years of the bank but we only know that $25,000 were incinerated on 23 March 1899{footnote}Report of Interventor Ahumada, 29 July 1899{/footnote}, $48,075 were incinerated on 8 July 1899 and $200,000 on 24 September 1899. In its Memoria de las Instituciones de Crédito 1897-1899 the Secretaría de Hacienda y Crédito Público reported that up to 31 December 1899 $1,005,000 had been authorised, of which $293,075 had been amortised, $469,710 was in circulation and the remaining $242,215 was in the head office or the branches{footnote} Memoria de las Instituciones de Crédito 1897, 1898, 1899{/footnote}. So if these are correct, another $20,000 had been withdrawn some time before the end of 1899.

The following table records the withdrawal and destruction of Banco Comercial notes after its merger with the Banco Minero.

| 25c | 50c | $1 | $5 | $10 | $20 | $50 | $100 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opening balance at 1 July 1900 |

1,855.00 | 1,602.00 | 11,563.00 | 155,830.00 | 95,470.00 | 136,980.00 | 74,400.00 | 148,300.00 | 626,000.00 |

| Incinerations | |||||||||

| 16 July 1900 | 2,000.00 | 10,000.00 | 7,000.00 | 2,000.00 | 21,000.00 | ||||

| 6 September 1900 | 1.50 | 2,800.00 | 6,100.00 | 8,901.50 | |||||

| 24 September 1900 | 860.00 | 840.00 | 5,000.00 | 6,700.00 | |||||

| 28 May 1901 | 100.00 | 5,200.00 | 1,500.00 | 6,800.00 | |||||

| 24 September 1901 | 25.00 | 50.00 | 600.00 | 970.00 | 450.00 | 800.00 | 2,895.00 | ||

| 24 March 1902 | 25.00 | 600.00 | 2,080.00 | 120.00 | 120.00 | 50.00 | 2,995.00 | ||

| 30 June 1902 | 200.00 | 2,575.00 | 140.00 | 520.00 | 400.00 | 500.00 | 4,335.00 | ||

| 10 September 1902 | 19.75 | 127.00 | 2,365.00 | 1,140.00 | 560.00 | 350.00 | 300.00 | 4,861.75 | |

| 27 November 1902 | 1,770.00 | 170.00 | 380.00 | 400.00 | 100.00 | 2,820.00 | |||

| 16 April 1903 | 4.50 | 23.50 | 9.00 | 10,045.00 | 2,000.00 | 1,420.00 | 650.00 | 1,200.00 | 15,352.00 |

| 29 August 1903 | 7,000.00 | 1,000.00 | 1,000.00 | 9,000.00 | |||||

| 23 November 1903 | 1.00 | 7,130.00 | 2,650.00 | 1,440.00 | 1,200.00 | 1,000.00 | 13,421.00 | ||

| 13 February 1904 | 5,915.00 | 1,800.00 | 1,400.00 | 500.00 | 9,615.00 | ||||

| 28 May 1904 | 2.50 | 18.50 | 6,165.00 | 2,250.00 | 1,540.00 | 1,100.00 | 600.00 | 11,676.00 | |

| 27 October 1904 | 6,000.00 | 2,000.00 | 8,000.00 | ||||||

| 11 November 1904 | 3,500.00 | 1,000.00 | 1,000.00 | 5,500.00 | |||||

| 30 January 1905 | 0.25 | 0.50 | 4,340.00 | 2,120.00 | 1,000.00 | 600.00 | 8,060.75 | ||

| 28 March 1905 | 10,995.00 | 1,000.00 | 11,995.00 | ||||||

| 17 June 1905 | 7,500.00 | 5,000.00 | 3,000.00 | 15,500.00 | |||||

| 25 July 1905 | 3,555.00 | 4,410.00 | 4,040.00 | 2,100.00 | 2,200.00 | 16,305.00 | |||

| 8 November 1905 | 10,000.00 | 8,000.00 | 4,000.00 | 22,000.00 | |||||

| 28 November 1905 | 4,000.00 | 2,720.00 | 3,360.00 | 2,300.00 | 2,900.00 | 15,280.00 | |||

| 27 March 1906 | 3.50 | 4.00 | 8,240.00 | 4,490.00 | 5,420.00 | 2,050.00 | 8,100.00 | 28,307.50 | |

| 26 June 1906 | 9,855.00 | 5,000.00 | 5,000.00 | 2,650.00 | 3,500.00 | 26,005.00 | |||

| 30 July 1906 | 3,000.00 | 2,000.00 | 2,000.00 | 7,000.00 | |||||

| 1 September 1906 | 2.25 | 1.00 | 16.00 | 2,865.00 | 1,640.00 | 1,640.00 | 1,350.00 | 3,900.00 | 11,414.25 |

| 24 October 1906 | 3,315.00 | 1,540.00 | 1,540.00 | 950.00 | 2,000.00 | 9,345.00 | |||

| 11 May 1907 | 9,000.00 | 9,000.00 | |||||||

| 23 July 1907 | 2,380.00 | 7,910.00 | 8,260.00 | 4,250.00 | 7,500.00 | 30,300.00 | |||

| 30 October 1907 | 2,400.00 | 3,040.00 | 5,620.00 | 2,650.00 | 6,200.00 | 18,910.00 | |||

| 12 May 1908 | 3,000.00 | 9,000.00 | 24,000.00 | 15,000.00 | 40,000.00 | 91,000.00 | |||

| 21 October 1908 | 1,000.00 | 5,000.00 | 16,000.00 | 5,000.00 | 15,000.00 | 42,000.00 | |||

| 24 April 1909 | 500.00 | 4,000.00 | 16,000.00 | 5,000.00 | 15,000.00 | 40,500.00 | |||

| 6 September 1909 | 1,000.00 | 1,000.00 | 4,000.00 | 5,000.00 | 5,000.00 | 16,000.00 | |||

| 24 February 1910 | 1,000.00 | 2,000.00 | 3,000.00 | ||||||

| 31 August 1910 | 100.00 | 1,000.00 | 2,000.00 | 10,000.00 | 13,100.00 | ||||

| 31 December 1910 | 1,000.00 | 5,000.00 | 6,000.00 | ||||||

| 22 February 1911 | 5,780.00 | 9,350.00 | 9,100.00 | 24,230.00 | |||||

| 29 July 1911 | 0.50 | 380.00 | 2,300.00 | 2,680.50 | |||||

| Balance as at 15 April 1912{footnote}CEHM, Fondo Creel, 85, 21975. Note error in $100 column{/footnote} | 1,775.75 | 1,402.00 | 7.00 | 10.00 | 100.00 | 8,600.00 | 1,150.00 | 12,300.00 | 25,344.75 |

| 28 April 1913 | 2,000.00 | 2,000.00 | |||||||

| 19 June 1913 | 280.00 | 800.00 | 1,080.00 | ||||||

| Balance as at November 1913{footnote}ST papers, Part I, box 84, account as of 25 November 1913 produced for Silvestre Terrazas by S. Goyenche, after studying what books he had of the Banco Minero, 23 November 1914{/footnote} |

1,775.75 | 1,402.00 | 7.00 | 10.00 | 100.00 | 6,320.00 | 350.00 | 10,000.00 | 19,964.75 |

| 24 March 1920 | 10.00 | 100.00 | 1,080.00 | 350.00 | 1,800.00 | 3,340.00 | |||

| 30 March 1920 | 5.00 | 5.00 | |||||||

| 7 October 1926 | 2.00 | 2.00 | |||||||

| 11 October 1926 | 300.00 | 300.00 | |||||||

| 20 May 1927 | 200.00 | 200.00 | |||||||

| Balance as at 20 March 1929 |

1,775.75 | 1,402.00 | 5,040.00 | 7,900.00 | 16,117.75 | ||||

| Number of notes as at 20 March 1929 |

7,103 | 2,804 | 252 | 79 | 10,238 |

In fact, these records are faulty, as is obvious from the fact that $1, $5, $10 and $50 notes still exist. On 15 January 1920 Juan Creel, from El Paso, wrote to Enrique Creel asking about notes of the Banco Comercial and Banco Mexicano. The notes that he had in El Paso that could be incinerated he had sent to Mexico City to be destroyed, but in Mexico there were some notes that were of the denominations that had been filled up (de las denominaciones cuya emisión está agotada), whilst Sr. Ginther still had $6,600 from the two banks in Santa Rosalía, and he had $2,400 in his office. He wanted to know what to do, since they could not be officially incinerated{footnote}CEHM, Fondo Creel, 251, 64310{/footnote}. Enrique told him to destroy them, keeping a record of the fact in the bank’s confidential files, without making any entry in the bank’s accounts, and to make up the amount by deducting it from the sale of some securities (unless he had a better idea){footnote} CEHM, Fondo Creel, 252, 64599, letter Enrique C. Creel, Los Angeles to Juan A. Creel, El Paso, 19 January 1920{/footnote}. Juan agreed{footnote}CEHM, Fondo Creel, 251, 64335{/footnote}.

In March 1931 the Comité Liquidador de los Antiguos Bancos de Emisión started an investigation to determine whether the balance of the Banco Comercial’s notes had been incorporated into the Banco Minero’s balance of outstanding notes, or was included in its “Old Accounts (Cuentas Antiguas)”. If the former was the case, any outstanding Banco Comercial notes would have been demonetized from 1 March 1931 (according to the 30 August 1930 decree) but if the latter, they would still have a value, as not being banknotes but a particular kind of security{footnote}El Revolucionario, 17 March 1931{/footnote}. Does this suggest that someone still had a substantial amount in these notes?