El Oro

A description of El Oro informed the reader that "The little town of El Oro is 108 miles by rail northwest from the City of Mexico, and is reached by a narrow-gauge branch of the Mexican National railroad to Tultenango, from which station the El Oro Mining & Railway Co’s local railway bring the traveler to El Oro itself. The mine is thus placed with easy reach of a large city." The article also gives a very patronising description of working conditions and pay"On the whole, the native labour of the El Oro district is exceptionally good, but the population of the district is insufficient for the demand made by expanding mining operations, therefore workmen have been obtained from other districts, such as Pachuca and Zacatecas. It has also been found necessary to increase the wages of the peon, or day labourer, so that it is nearly double what it used to be ten years ago. Thus, in 1897 the rate was 37½ centavos, while in 1908 this same class of labour commanded 62½ to 75 centavos per shift. Furthermore, while the rate of wages has increased the amount of labour performed per individual has suffered a decrease ; in other words, the efficiency of ordinary labour has decreased to a serious extent. It is characteristic of the Mexican native that the more pay he receives the less work he will perform ; if he can earn sufficient for his needs by working three days per week, he does not see the philosophy of working for six days. Surplus earnings are chiefly devoted to the purchase of pulque and other intoxicants, as well as other luxuries not conducive to physical fitness. It is true that the cost of living has increased and this has operated in a measure as a counterirritant, so to speak, against a tendency toward idleness. Importations from elsewhere have not proved an unqualified success because the natives are reluctant to leave their tierra, or home place, and it is only the most venturesome, and the least responsible, that do so ; and the best of these are apt to drift back to the place of their origin as soon as they have accumulated a little money. Many devices were tried to attract labour to El Oro; one of these was to pay a bonus for continuous work. It was customary to pay once a week, namely on Sunday, with the result that if any money was left on hand by Monday morning, the workmen were disinclined to go to work; by paying every day, however, the native got his money gradually, instead of receiving a lump sum, and as he spent it in the manner in which he received it, he was more likely to be in a fit state for work when he received his pay daily. However, it was also found necessary to introduce some form of contract, or task work, payment being made on results, as measured by the metre or by the ton. At the Esperanza the contract system was elaborated so as to include practically all classes of labour, the idea being to diminish the proportion of men at day's pay so that the expense of superintendence could also be reduced to a minimum. For breaking ore the price varied from 6 to 12 pesos per square set, in oxidised ore, and from 10 to 20 pesos per square set in sulphide ore; drifts and cross-cuts cost 20 to 40 pesos per linear metre; raises, 25 to 40; winzes, 30 pesos and upward. For timbering, 1 peso was paid per post, or 5 to 15 pesos per set. For tramming, the price varied from 15 to 20 centavos per car when filling from chutes, but the price was raised to 25 centavos when it became necessary to shovel. The ordinary labourer in a mill was paid 75 centavos per 12 hours. These figures will give some idea of the range of prices. It is proper to say that Mexican labour is not cheap, but if properly handled it is fairly satisfactory. Owing to the natural improvidence of the native workman, he never saves enough to keep his family more than a week or so; this effectually prevents serious strikes. Moreover, strikes and similar outbreaks are quickly repressed by the officials of the Mexican Government, so that any agglomeration of individuals planning to make such a move to the detriment of industry has to reckon upon repression from the authorities. As a rule the natives can be taught to use modern methods and machinery, but it is a slow process, requiring both time and patience, especially if the act required is another way of doing something they have been accustomed to do in their own way; for example, great difficulty was found in enforcing a Mexican assayer to use a modern muffle furnace instead of the old ‘pot’ furnace, to which he had been accustomed; the stopping of the custom of ceasing work in the middle of the forenoon and eating almuerzo, or breakfast, required months; and accustoming the native machinists to the use of modern highspeed steel on lathe and planer was an arduous undertaking; in fact, the breaking up of any old custom by the introduction of innovations was always attended with great difficulty and met with persistent opposition." (W. E. Hindry, “The Esperanza Mine, El Oro, Mexico” in The Mining Magazine, Vol. I, No. 2, October 1909).

By January 1914 all the El Oro companies were already using scrip. Permission from the Government to issue this paper was requested by the companies but was refused because of the federal law against such issues. However, they were verbally advised that in case such issues were made, nothing would be done towards their prosecution. However, the Minister of Hacienda also stated that if arrangements could be made to make paper money issued by the mining companies legal, a great obstacle would be that each vale would have to carry four centavos in revenue stamps. On vales of five centavos, therefore, 80% would be charged in stampsAHMM, Fondo Norteamericano, vol. 41, exp. 15, Dirección General, Correspondencia, Mar 1913 – Nov 1914 Weekly gossip letter 26 January 1914.

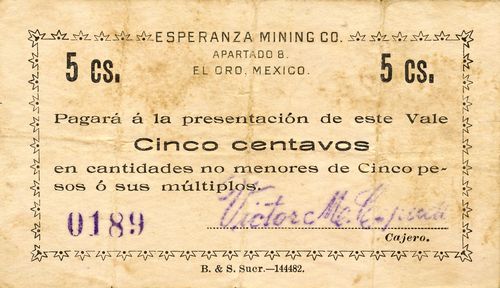

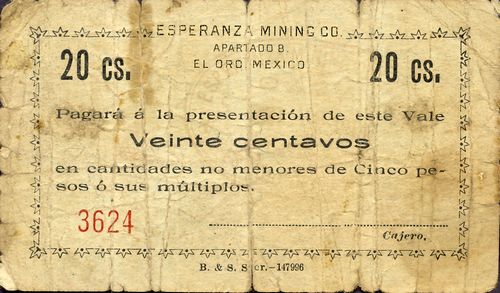

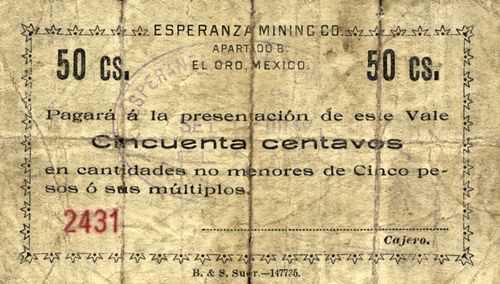

Esperanza Mining Company

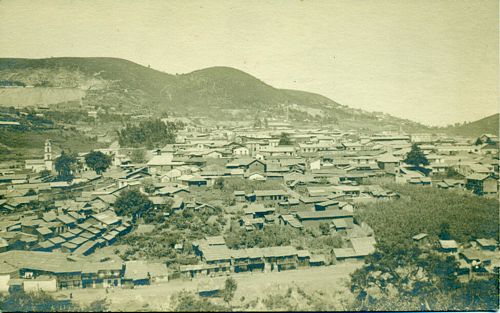

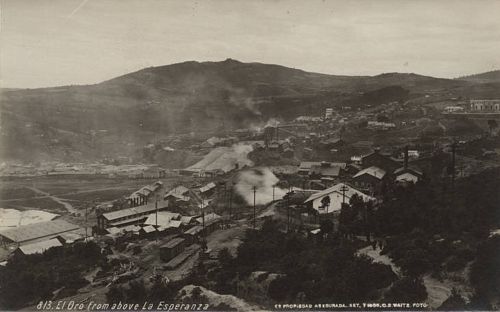

El Oro from above La Esperanza, 1904

(courtesy DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University)

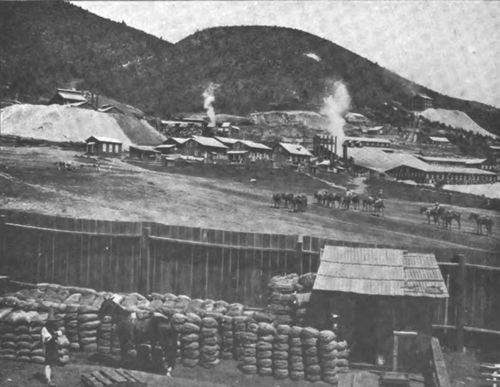

The Esperanza mine was originally "denounced" or located in 1890 by August Sahlberg, a Norwegian, who had been foreman, and later, superintendent of the El Oro mine, which adjoins the Esperanza on the south. At the time when he was superintendent of the El Oro mine the San Rafael vein was the principal lode and Sahlberg thought that the vein continued in the direction of the Esperanza. However, to get working capital he had to surrender the larger part of his interest but was allowed to remain in charge of the mine itself. In 1895 he increased the holdings of the company and changed the name to Compañía Minera La Esperanza y Anexas, S.A., with a capitalization of $300,000. The mine began to pay dividends, and, with his dividends Sahlberg commenced to buy back the shares that he had hypothecated, until he became one of the chief owners. In 1903, John Hays Hammond secured an option on the property for the Guggenheim Exploration Company and after a thorough examination the mine was bought by the Guggenheims for $4,500,000. The new company was called the Esperanza Mining Company of New York; the majority of the stock was placed on the London market and a subsidiary English company was formed under the name of Esperanza Limited. In 1906 the Esperanza mine became the most productive gold mine in the world, but production then tailed off.

We know of a series (5c, 20c and 50c) produced by Bouligny & Schmidt, Sucrs., of Mexico City. Known notes are dated 15 August 1914.

| from | to | total number |

total value |

||

| 5c | 0001 | includes number 0189 | |||

| 20c | includes numbers 3624 to 3714CNBanxico #11476 | ||||

| 50c | includes numbers 2431 to 6685CNBanxico #11477 |

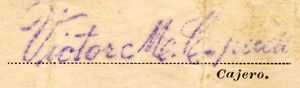

The stamped signature is of the cajero, Victor Mc[ ][identification needed].

| Victor |  |

On 30 September 1914 an Inspector of the Departamento de Trabajo. R. Pérez L. reported:

The financial situation in the Mineral is desperate, in view of the large issue of paper money, in fractions of 1, 5, 10, 20 and 50 centavos, that has been forced into circulation by the Dos Estrellas and Esperanza mines. This currency has value only within the small radius of the town and for this reason the workers are forced to purchase their basic necessities at high prices in the companies’ establishments, since the aforementioned notes are only accepted only within the small radius of action, thereby prejudicing their interests, they may be unable to go out to obtain lower prices in any other place because of the large issue made by the aforementioned mines. The number of workers currently out of work, according to reports I was able to obtain, reaches the considerable number of more than 4,000 workers in the different paralyzed mines.GN, Ramo del Trabajo, caja 72, exp. 5, ff. 11-15.

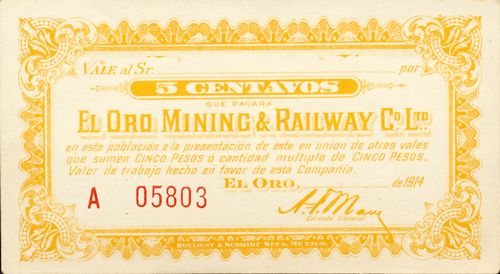

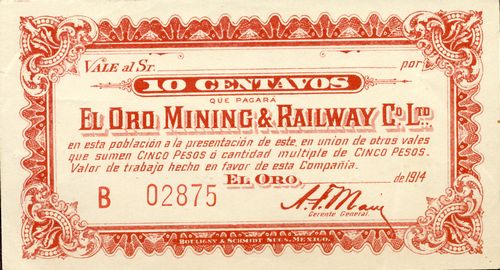

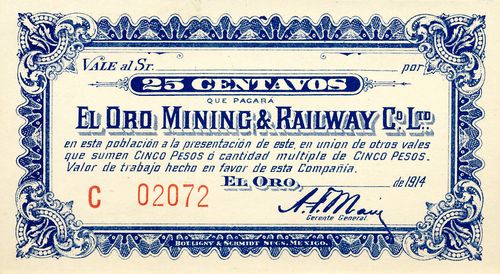

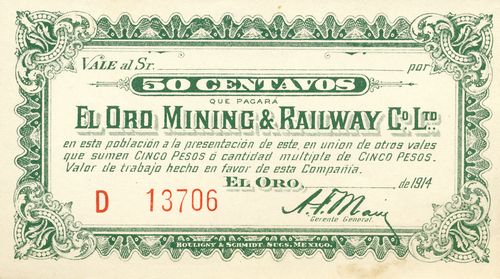

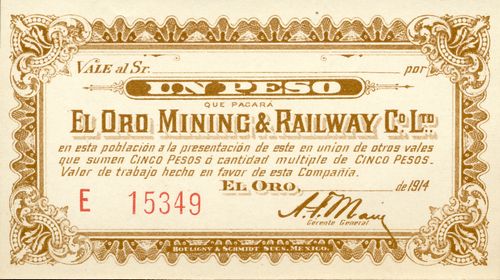

El Oro Mining & Railway Company Limited

The El Oro Mining and Railway company ordered a considerable amount in vales from Bouligny & Schmidt, Sucs., of Mexico City. On 13 January 1914 the Mexican Herald reported that "The scarcity of fractional coinage has necessitated the El Oro Mining company and the El Oro Mining and Railway company in El Oro, Mexico, issuing vales of five, ten, twenty-five, and fifty cents and of one peso, to meet the requirements of their weekly pay-rolls. These vales are exchanged when required at the office of the companies, the local bank of the state bank of Mexico, and are accepted at their face value in all commercial houses in making purchases. This action of the companies is appreciated by the employees"The Mexican Herald, 19th Year, No. 6,709, 13 January 1914. In early February it was reported that they would probably be put into circulation in the immediate futureThe Mexican Herald, 19th Year, No. 6,735, 9 February 1914.

| Series | from | to | total number |

total value |

||

| 5c | A | includes numbers 04536CNBanxico #11478 to 05803 | ||||

| 10c | B | includes numbers 02875 to 04612CNBanxico #11479 | ||||

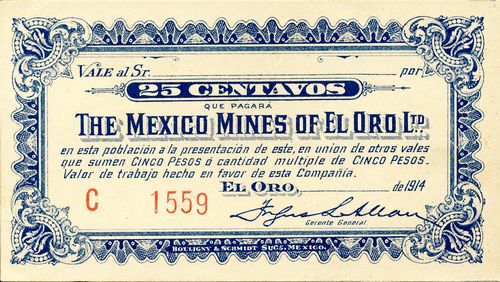

| 25c | C | includes number 02072 | ||||

| 50c | D | includes numbers 06354 to 13706 | ||||

| $1 | E | includes numbers 04761CNBanxico #11482 to 18557 |

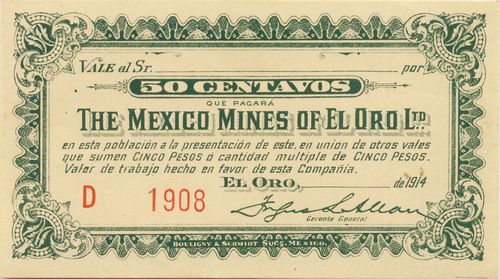

These were vales made out to a named recipient, as payment for work done (Valor de trabajo hecho en favor de esta Compañía) which the company would redeem in multiples of five pesos. They carry the printed signature of Alfred F. Main, who also signed a similar issue for the Compañía de Minas la Blanca y Anexas in Pachuca, Hidalgo.

| Alfred F. Main became the resident manager in 1909. |  |

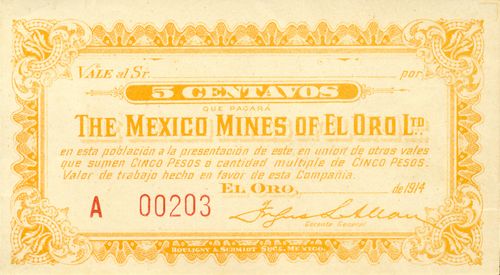

The Mexican Mines of El Oro Limited

A 1909 report stated "This company is an offshoot of the El Oro and is under the control of the Exploration Company. The management is in the same hands as the El Oro, A. F. Main being general manager and R. M. Raymond local director. Fergus Allan is mine superintendent. The mine is situated immediately north of the Esperanza, which in its turn is north of the El Oro".

The Mexican Mines of El Oro Limited issued an identical series of vales, presumably at the same time.

Presumably a 10c, so

| Series | from | to | total number |

total value |

||

| 5c | A | 00001 | includes number 00203 | |||

| 10c | B | |||||

| 25c | C | includes numbers 1559 to 1572 | ||||

| 50c | D | includes numbers 1902CNBanxico #11481 to 1908 | ||||

| $1 | E |

These carried the printed signature of Fergus L. Allan as General Manager (Gerente General).

|

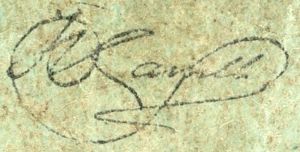

Fergus L. Allan He died in November 1920 while still general managerThe Mining Magazine, vol. XXIV, no. 3, March 1921. |

|

By March El Oro and Pachuca, in the state of Hidalgo, were the only places where vales were being usedAHMM, Fondo Norteamericano, vol. 41, exp. 15, Dirección General, Correspondencia, Mar 1913 – Nov 1914 Weekly gossip letter 23 March 1914.

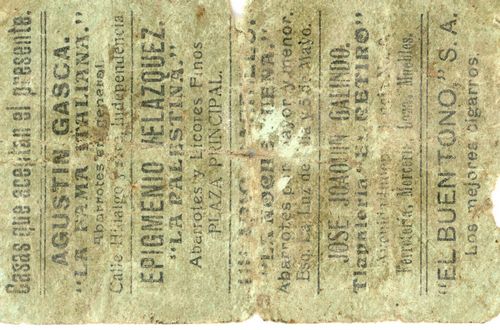

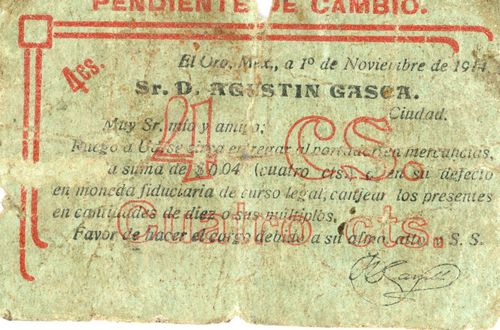

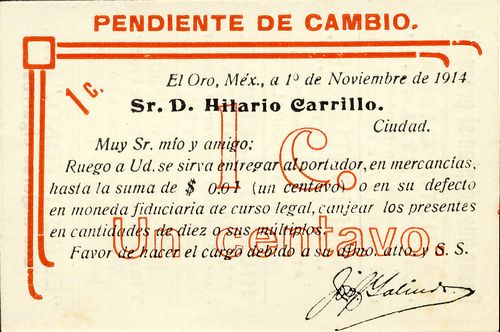

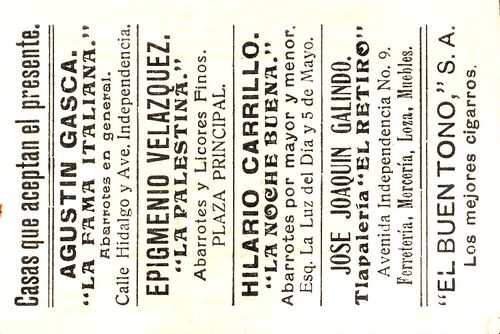

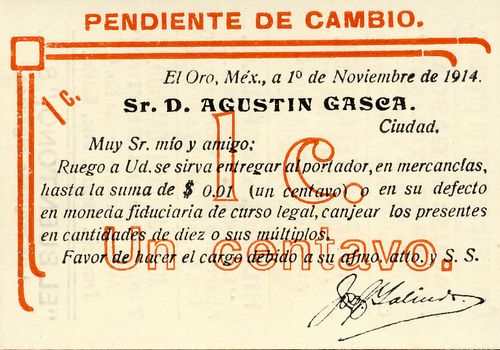

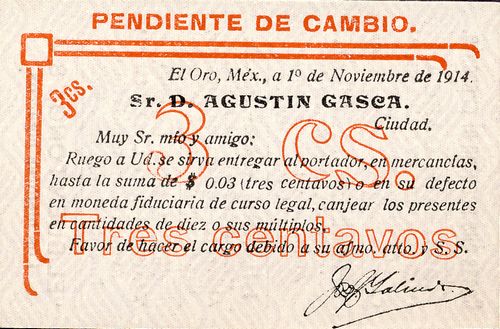

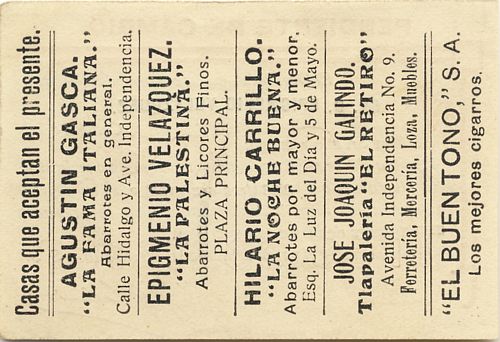

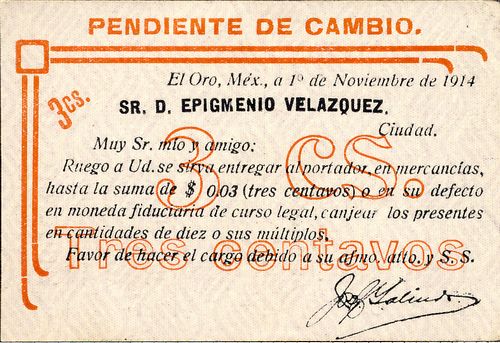

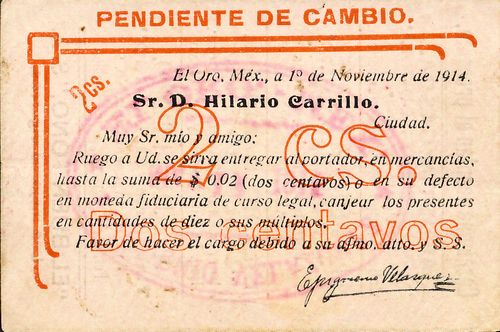

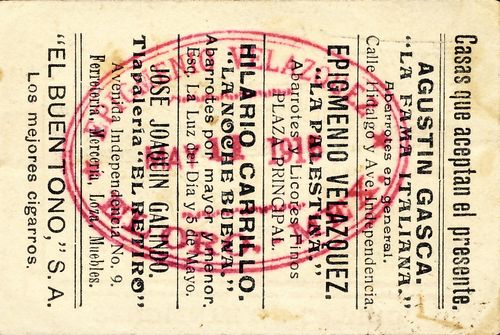

Various merchants

This set of notes dated 1 November 1914 are entitled “PENDIENTE DE CAMBIO” and were drawn on one merchant and asked another merchant to entrust the holder its value in merchandise. With four issuers, to three other payees, and at least five valuesDick Long, in his November 1974 auction, had a 10c note[image needed], listed as Hilario Carrillo but that would have been as payee, there could have been up to sixty permuations. They could be redeemed in multiples of ten pesos.

The four casas comerciales that issued and would accept the notes were:

Hilario Carrillo

|

Hilario Carrillo came from Guanajuato. He ran the "La Noche Buena", a wholesale and retail store (Abarottes por mayor y menor) at La Luz del Día and 5 de Mayo. In 1915 he moved to Toluca and set up in partnership with his brother-in-law Agustín Casca. |

|

We know of a 4c note addressed to Agustín Garza.

José Joaquín Galindo

| José Joaquín Galindo, of the hardware store (tlapaleria) "El Retiro" at Avenida Independencia no. 9, offered paint, electrical goods, ironmongery, haberdashery and furniture (Ferreteria, Mercería, Lata, Muebles). |  |

We know of 1c notes addressed to Hilario Carrillo

and of 1c and 3c notes addressed to Agustín Casca

and 3c notes addressed to Epigmenio Velázquez

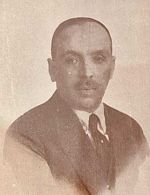

Agustín Gasca

Agustín Gasca Mireles was born in Mineral de Pozos, Guanajuato, on 28 May 1886. At the age of 13 he began working in a soap factory and at 15 he was employed as a caretaker in the Angustias mine. Three years later he moved to Pachuca, Hidalgo, and later, knowing of the bonanza at El Oro, established a small grocery business there. By 1913 he was the owner of the "La Noche Buena", "La Esmeralda" and "La Vencedora" stores. These note refer to the grocery (Abarrotes en general) "La Fama Italiana" at Calle Hidalgo and Avenida Independencia,. Because of the trouble caused by marauding parties of revolutionary soldiers Casca decided to settle in the city of Morelia, Michoacán, but on 20 February 1915 the only train available was to Toluca. For a long time communications between Mexico City and El Oro were interrupted, so Casca decided to sell his properties in El Oro and with his brother-in-law Hilario Carrillo formed a small company called Carrillo Gasca. Then in 1919 he decided to establish his own business on the corner of Libertad (now Hidalgo) and Galeana. In 1924, he was elected Presidente Municipal of Toluca and later was a deputy in the local Congress. In 1929 he was elected Presidente Municipal for a second time. He was one of the founders of the Partido Socialista del Trabajo, which during the government of President Plutarco Elías Calles, merged with others to form the Partido Nacional Revolucionario of which he was also a founder; this institution years later took the name Partido Revolucionario Institucional. By 1932 Casca moved away from political activity to devote himself entirely to his grocery, hardware and beer distribution businesses. |

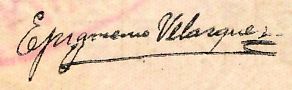

Epigmenio Velázquez

| Epigmenio Velázquez Rivera was also born in Pozos, Guanajuato, in 1884. At an early age he moved to El Oro, together with his friend Agustín Gasca Mireles from the same place and both young men engaged in trade. Velázquez ran "La Palestina", a grocery and liquorstore (Abarottes y Licores Finos) in the Plaza Principal. However, the depredations that he experienced during the Revolution left him economically devastated, so he decided to emigrate to Toluca in 1930. |  |

We known of a 2c note drawn on Hilario Carrillo, dated 11 May 1915

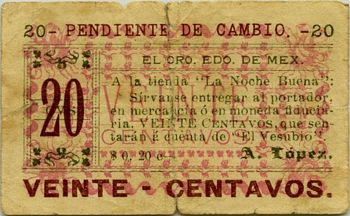

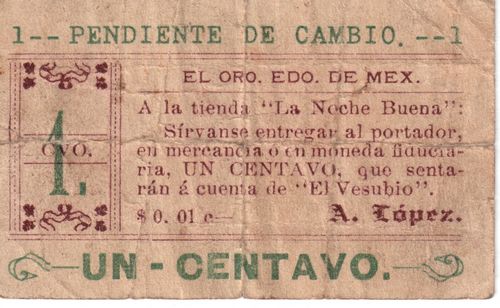

A. López

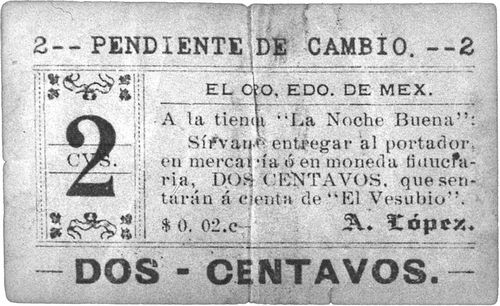

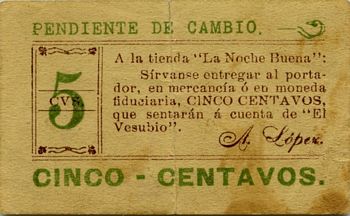

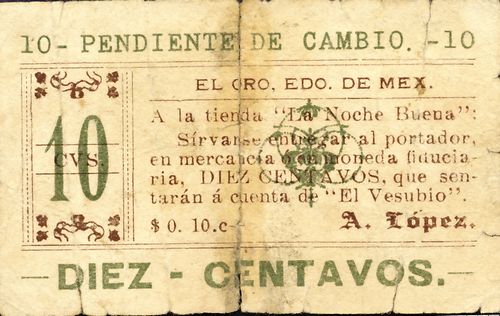

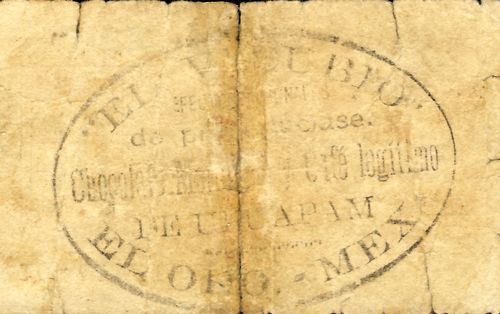

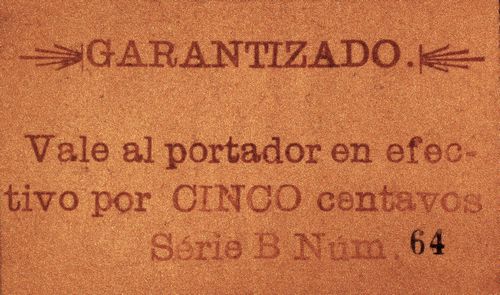

Another series of notes (1c, 2c, 5c and 10c) issued by A. López of "El Vesubio" asked Hilario Carrillo's "La Noche Buena" to give the holder its value in merchandise or currency and to charge "El Vesubio"’s account.

Administración de Correos

| series | from | to | total number |

total value |

||

| 5c | B | includes number 64 |