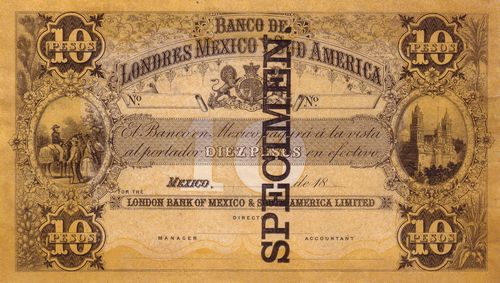

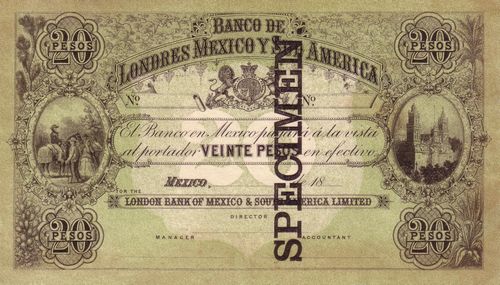

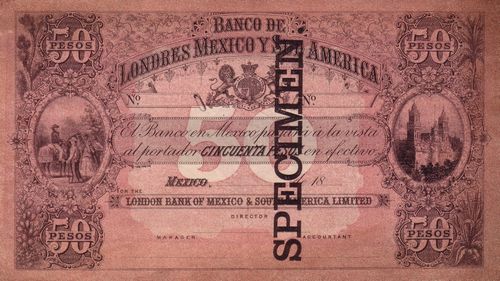

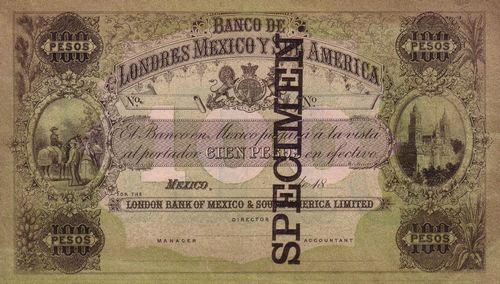

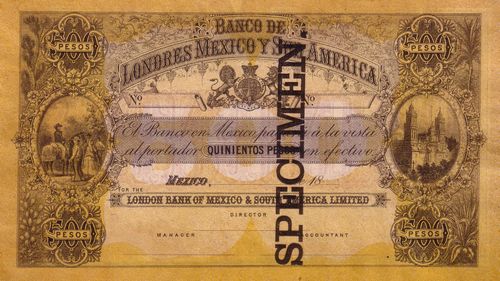

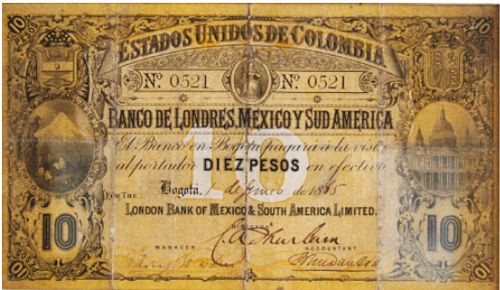

First issue

The first issue of notes was a series from $5 to $500.

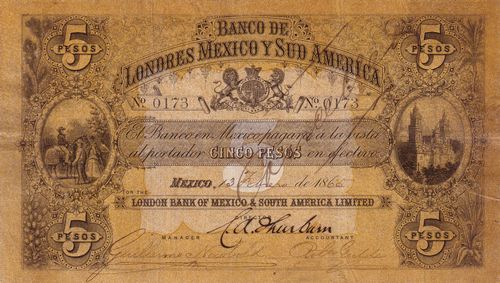

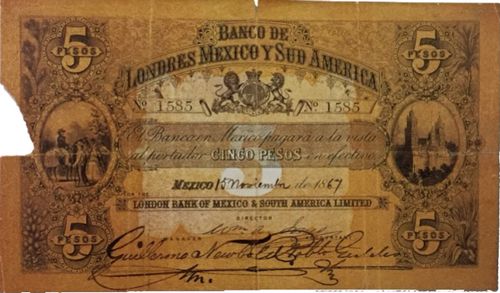

Issued notes

| date of issue | date on note | from | to | Director | Manager | Accountant | ||

| $5 | 13 February 1865 | 0001 | 0280 | Thurburn | Newbold | Geddes | includes number 0173 | |

| 15 November 1867 | Jones | Newbold | Geddes | includes number 1585 | ||||

| $10 | 6 May 1865 | |||||||

| 16 July 1865 | ||||||||

| $20 | 6 May 1865 | |||||||

| 16 July 1865 | ||||||||

| $50 | 6 May 1865 | |||||||

| 16 May 1865 | ||||||||

| $100 | 5 March 1866 | |||||||

| 4 June 1866 | ||||||||

| $500 | 5 March 1866 | |||||||

| 4 June 1866 |

Design features

The design of these notes is discussed in "Historial imagery".

Printers

We do not know with absolute certainty who printed these notes. In his overview of the bank’s issuesJosé Herrera Cedillo, Apunte para la historia numismática del papel moneda del Banco de Londres México y Sud-America,(Sociedad Numismática de México, 1981 Herrera Cedillo attributed the printing of the notes to the firm “J. H. Sanders of London,” but this attribution is unlikely as there was no security printer named J. H. Sanders in London at the time. There was a “T. H. Saunders,” but it was not a printer. It was a manufacturer of security paper, although it sometimes arranged the printing of notes by major London currency printers.

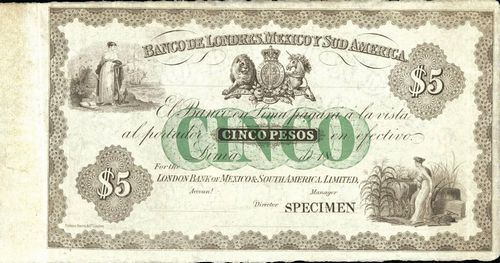

As leading security stationers, Saunders could well have supplied the paper, but which firm might it have subcontracted for the printing? Perhaps a clue might be found in the London printers used by the bank in its early years: the Mexico City branch employed both Thomas de la Rue and Bradbury Wilkinson whilst the Lima, Peru office also engaged Perkins, Bacon and Company.

The Perkins and Bacon notes from Lima share several key features with these first Mexican notes. These similarities may have been dictated by the bank, but they may also point to a common printer (a package deal?).

These similarities are:

| Comparable proportions | Parallel explanatory texts |

| An arching banner with the bank’s name | One design for all the denominations |

| The British coat of arms at the centre | Use of two different colours, with colours varying by value. |

| Dual lateral vignettes |

The bank produced a similar note for its operations in Bogota, Colombia.

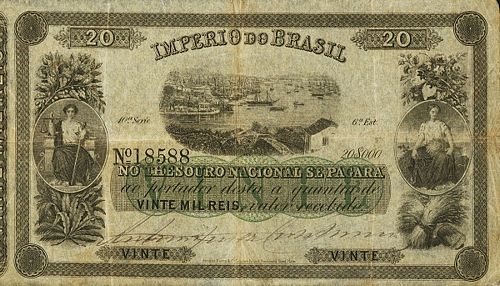

Other notes printed by Perkins and Bacon at the same time bear certain resemblances to the Mexican notes, which suggest that the likeness may be down to a shared printer, not the bank, as seen in these Brazilian examples.

These were:

| Comparable proportions | Dual lateral vignettes |

| Arching banners | Four plants in the corners |

| Florid vine motifs | Two colours, differing by denomination |

| Ornate cartouches |

.

The coat of arms on the 10,000 reis note has two supporters, and so is structurally similar to the Mexican notes. In fact, the Brazilian coat of arms at this time did not have these figures, which have been added by the printers.

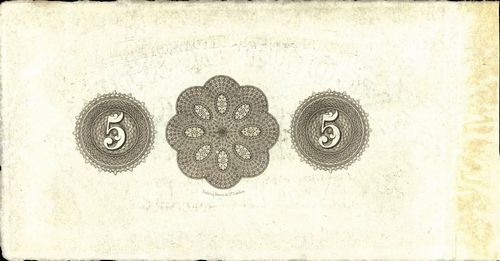

However, we need to add a caution. The parallels noted here may be too general. Other British imprints from the same era sometimes share such features. Thus a 50 pesetas note from Spain subcontracted by Saunders to Bradbury and Wilkinson bears similarities to the front whilst the $5 of the Banco de Londres, México y Sud America printed by Thomas de la Rue resembles the backs. So we cannot say with complete confidence that Perkins and Bacon were the printers.

Finally, the register of these notes carry the label of a little known stationer, “William Morrison & Sons”. Could it have been the printer?

There are reasons to question this prospect. The firm probably produced the book rather than the notes registered in it and it is hard to believe than an almost unknown stationer could have printed notes of such high quality. Nevertheless, there are compelling reasons at least to contemplate the possibility.

Firstly, we should note that later registers do have the label of Bradbury Wilkinson, the printer of the notes and probably not the books. Secondly, one of the principals of the stationers (possibly a son) was named William Thomas Morrison, the same as the manager of the bank. Whilst the surname is common in English, the combination with the given names is not. These will not have been the same person (the manager of the bank was an experienced attorney, and stationer to bank-manager is not an obvious career progression) but could they be related (uncle or cousin) and the bank manager have given the printing order to his relation’s firm?

So, although Perkins and Bacon remain the most probable printers, we still cannot say with certain who produced these magnificent notes.

(based on a presentation given by Peter S, Dunham, Ph. D.)