The Monclova issue

As soon as Carranza had taken the step of disowning Huerta, he realised that financing his revolution would be a problem. He could not simply requisition food, clothing and other military supplies as this action would have created social chaos and cash was needed to buy arms and ammunition from foreign sources. Carranza realised that he had to organise a fiscal system that would establish a means of payment acceptable to the people of Mexico and to obtain the gold for foreign expenditures. The banks would not help him, but anyway he was opposed to obtaining foreign loans or loans from individuals or banks because he felt this would put the revolution at the mercy of the lenders.

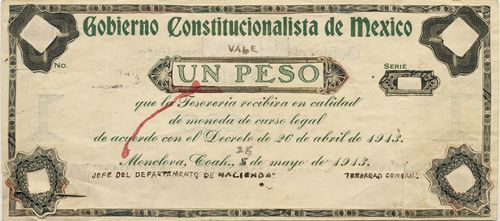

Officially, financing his revolution depended upon a combination of paper money, which created a public debt that did not directly affect a given group of Mexicans or foreigners, and export taxes used to obtain hard currency to spend on munitions. Roberto V. Pesqueira, on 31 March 1913, writing from Douglas, Arizona, had suggested to Carranza a common paper currency for the three northern states under Constitutionalist control for economic and propaganda purposesAIF, RM/II. I-015. Carranza's decree issued at Piedras Negras, Coahuila on 26 April 1913 ‘considering it the duty of all Mexicans to contribute proportionally towards the expenses of the army until the re-establishment of constitutional order, and considering finally that the best way to achieve these ends, without causing direct and material injury to the people of the country, lies in the creation of paper money’ specified the creation of an internal debt of $5,000,000. All the inhabitants of the Republic were obliged to receive these notes as legal tender, and at their face value, in all civil and commercial transactions. As soon as order was re-established, laws would be promulgated on the redemption of the notes that had been issued.

The notes were printed by the Norris Peters Company who were based at 458-460 Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington, D.C. On 9 May Pesqueira, then in Washington and in charge of the issue, sent Carranza, via Félix Sommerfield, a proof for approvalAIF, RM/II. I-015 Roberto V. Pesqueira, Washington, D.C. to Carranza, Piedras Negras, 9 May 1913. Carranza, in Piedras Negras, agreed, if the paper, printing and signature were fine (en buen papel y bonita impresión y firma)AIF, RM/II. I-015 Carranza, Piedras Negras, 14 May 1913. It is strange that he mentions signature: obviously at this time he expected them to be printed on the notes.

An early mock-up of the Monclova issue

At the begining of June Manuel Pérez Romero, who worked with Pesqueira, asked Carranza, to send proofs of the signatures to be printed in facsimile on the notesAIF, RM/II. I-003 Manuel Pérez Romero, Washington, D.C., to Carranza, Piedras Negras, 11 June 19133. Carranza replied that the signatures had to be original and so told them to tell the printer to leave the spaces blank, then the notes would be validated with autograph signatures AIF, RM/II. I-003 Carranza, Piedras Negras, 17 June 1913. So the print was delayed.

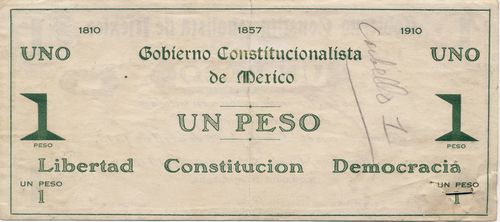

On 28 December, while at Hermosillo, Sonora Carranza decreed (decreto núm. 14) a second issue of fifteen million pesos (in notes of $1, $5, $10 and $20). This decree also prohibited the use of scrip (fichas, tarjetas ó vales) as currency, with punishment for anyone who issued or used them. Finally, on 12 February 1914, while he was at Culiacán, Sinaloa, Carranza added a further issue of ten million pesos (decreto núm. 18), bringing the total at this time to thirty million pesos. By the end of March 1914 Carranza and his government had moved from Sonora to Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua.

In his informe to Congress in 1917 Carranza said that the first five million pesos were the Monclova issue whilst the remaining twenty-five million pesos were the Ejército ConstitucionalistaInforme of Carranza, 15 April 1915. However, the Monclova issue was at least thirty million pesos, as there were at least two issues and the second order, for twenty-five million pesos, was made before the 12 February decree (see "Print runs")CEHM, Fondo XXI, carpeta 6, legajo 767.

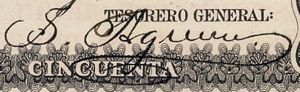

The notes were signed by Francisco Escudero, as Jefe del Departamento de Hacienda, and Serapio Aguirre, as Tesorero General.

|

In January 1914 Escudero was removed from his post for dishonourable conduct. It is said that he was given $125,000 pesos in banknotes to give to Francisco Villa as pay for his troops. $100,000 were said to have been perfectly good notes of the Banco Nacional de México and the Banco de Londres y México, while the rest were Sonoran notes. Escudero appropriated the good notes for his own use and paid Villa in nothing but the Constitutionalist notesThe Mexican Herald, 19th Year, No. 6,703, 7 January 1914: El Independiente, Año II, Núm. 319, 6 January 1914 tells a similar tale, but says that the sum concerned was $150,000. Escudero returned to Washington and was replaced by Manuel Bonilla. |

|

|

At the beginning of the 1910s he was Interventor (government-appointed auditor) of the Banco de Coahuila, and his signature appears on $20 notes dated 7 June 1910 and $10 notes dated 5 May 1912. He was the Maderista Presidente Municipal of Saltillo and then an early adherent to the Constitutionalist cause. He was appointed Tesorero General on 25 June 1913 when Carranza was in Sonora but removed from office in July 1914. He was later director of the Oficina Reselladora in Veracruz and of the Oficina Impresora del Timbre. He served for two years and was then, in October 1917, appointed Administrator of the customs at Ciudad JuárezEl Pueblo, Año III, Núm. 1082, 29 October 1917. He died on 13 April 1949, in Mexico City, at the age of 80. |

|

Francisco Escudero:

Francisco Escudero: Serapio Aguirre was born in Ramos Arizpe, Coahuila, on 14 November 1868.

Serapio Aguirre was born in Ramos Arizpe, Coahuila, on 14 November 1868.